Abstract

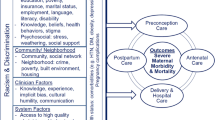

Thailand has high rates of maternity services; both antenatal care (ANC) and hospital delivery are widely used by its citizens. A recent Northern Thailand survey showed that Hmong women used maternity services at lower rates. Our objectives were to identify Hmong families’ socio-cultural reasons for using and not using maternity services, and suggest ways to improve Hmong women’s use of maternity services. In one Hmong village, we classified all 98 pregnancies in the previous 5 years into four categories: no ANC/home birth, ANC/home, no ANC/hospital, ANC/hospital. We conducted life-history case studies of 4 women from each category plus their 12 husbands, and 17 elders. We used grounded theory to guide qualitative analysis. Families not using maternity services considered pregnancy a normal process that only needed traditional home support. In addition, they disliked institutional processes that interfered with cultural birth practices, distrusted discriminatory personnel, and detested invasive, involuntary hospital procedures. Families using services perceived physical needs or potential delivery risks that could benefit from obstetrical assistance not available at home. While they disliked aspects of hospital births, they tolerated these conditions for access to obstetrical care they might need. Families also considered cost, travel distance, and time as structural issues. The families ultimately balanced their fear of delivering at home with their fear of delivering at the hospital. Providing health education about pregnancy risks, and changing healthcare practices to accommodate Hmong people’s desires for culturally-appropriate family-centered care, which are consistent with evidence-based obstetrics, might improve Hmong women’s use of maternity services.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Shiferaw, S., Spigt, M., Godefrooij, M., Melkamu, Y., & Tekie, M. (2013). Why do women prefer home births in Ethiopia? BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 13, 5. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-13-5.

Sychareun, V., Hansana, V., Somphet, V., Xayavong, S., Phengsavanh, A., & Popenoe, R. (2012). Reasons rural Laotians choose home deliveries over delivery at health facilities: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 12, 86. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-12-86.

Titaley, C. R., Hunter, C. L., Dibley, M. J., & Heywood, P. (2010). Why do some women still prefer traditional birth attendants and home delivery?: a qualitative study on delivery care services in West Java Province Indonesia. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 10, 43. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-485.

Tsegay, Y., Gebrehiwot, T., Goicolea, I., Edin, K., Lemma, H., & San Sebastian, M. (2013). Determinants of antenatal and delivery care utilization in Tigray region, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. International Journal for Equity in Health, 12, 30. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-12-30.

Gabrysch, S., & Campbell, O. M. R. (2009). Still too far to walk: Literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 9, 34. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-9-34.

Say, L., & Raine, R. (2007). A systematic review of inequalities in the use of maternal health care in developing countries: examining the scale of the problem and the importance of context. Bulletin World Health Organization, 85, 812–819. doi:10.2471/BLT.06.035659.

Simkhada, B., van Teijlingen, E. R., Porter, M., & Simkhada, P. (2007). Factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care in developing countries: systematic review of the literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 61(3), 244–260. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04532.x.

Kongsri, S., Limwattananon, S., Sirilak, S., Prakongsai, P., & Tangcharoensathien, V. (2011). Equity of access to and utilization of reproductive health services in Thailand: National Reproductive Health Survey data, 2006 and 2009. Reproductive Health Matters, 19(37), 86–97. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(11)37569-6.

Kunstadter, P. (2013). Ethnicity, socioeconomic characteristics, and knowledge, beliefs and attitudes about HIV among Yunnanese Chinese, Hmong, Lahu and Northern Thai in a North-western Thailand border district. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 15(Suppl 3), S383–S400. doi:10.1080/13691058.2013.814807.

Culhane-Pera, K. A., Sriphetcharawut, S., Thawsirichuchai, R., Yangyuenkun, W., & Kunstadter, P. (2014). Crossing borders in birthing practices: A Hmong village in Northern Thailand (1987–2013). Hmong Studies Journal, 15(2), 1–17.

Wibulpolprasert, S. (ed.). (2013). Thailand Health Profile 2008-2010. Bureau of Policy and Strategy, Ministry of Public Health. Bangkok: Thailand. http://www.moph.go.th/ops/thp/thp/en/index.php?id=288&group_=05&page=view_doc. Accessed 22 June 2014.

Morse, J. M., Stern, P. N., Corbin, J., Bowers, B., Charmaz, K., & Clarke, A. E. (Eds.). (2009). Developing grounded theory: The second generation. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Finlayson, K., & Downe, S. (2013). Why do women not use antenatal services in low- and middle-income countries? A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. PLoS Medicine, 10(1), e1001373. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.101373.

World Health Organization. (2009). Baby-friendly hospital initiative: Revised, updated, and expanded for integrated care. Section 2:Strengthening and sustaining the baby-friendly hospital initiative: a course for decision-makers. WHO, UNICEF, and Wellstart International. Geneva: WHO press. http://www.unicef.org/nutrition/files/BFHI_section_2_2009_eng.pdf. Accessed 13 December 2014.

Carroli, G., & Mignini, L. (2009). Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Systematic Review, 2, CD000081. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD00081.pub2.Review.

Bowser, D., & Hill, K. (2010). Exploring evidence for disrespect and abuse in facility-based childbirth: report of a landscape analysis. USAID-TRAction Project: Harvard School of Public Health University Research Co, LLC. 2010:1–57. http://www.mhtf.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/17/2013/02/Respectful_Care_at_Birth_9-20-101_Final.pdf. Accessed 13 December 2014.

Ho, J. J., Pattanittum, P., Japaraj, R. P., Turner, T., Swadpanich, U., Crowther, C. A., & SEA-ORCHID Study Group. (2010). Influence of training in the use and generation of evidence on episiotomy practice and perineal trauma. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 111(1), 13–18. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.04.035.

Festin, M. R., Laopaiboon, M., Pattanittum, P., Ewens, M. R., Henderson-Smart, D. J., Crowther, C. A., & SEA-ORCHID Study Group. (2009). Cesarean section in four South East Asian countries: reasons for, rates, associated care practices and health outcomes. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 9, 17. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-9-17.

Lumbiganon, P., Laopaiboon, M., Gülmezoglu, A. M., Souza, J. P., Taneepanichskul, S., Ruyan, P., et al. (2010). Method of delivery and pregnancy outcomes in Asia: the WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health 2007–2008. Lancet, 375(490–9), 2010. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61870-5. (Erratum in Lancet. 2010;376:1902).

Charoenboon, C., Srisupundit, K., & Tongsong, T. (2013). Rise in cesarean section rate over a 20-year period in a public sector hospital in northern Thailand. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 287, 47–52. doi:10.1007/s00404-012-2531-z.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. (2014). Obstetric care consensus No. 1: Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 123, 693–711. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000444441.04111.1d.

Souza, J. P., Gülmezoglu, A. M., Lumbiganon, P., Laopaiboon, M., Carroli, G., Fawole, B., & Ruyan, P. (2010). Caesarean section without medical indications is associated with an increased risk of adverse short- term maternal outcomes: the 2004–2008 WHO Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health. BMC Medicine, 8, 71. doi:10.1086/1741-7015-8-71.

Hodnett, E. D., Gates, S., Hofmeyr, G. J., & Sakala, C. (2013). Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Systematic Review, 2, CD003766. doi:10.1002/14651858.CDC003766.pub5.

Yuenyong, S., Jirapaet, V., & O’Brien, B. A. (2008). Support from a close female relative in labour: The ideal maternity nursing intervention in Thailand. Journal of Medical Association of Thailand, 91(2), 253–260.

World Health Organization. (2009). Integrated management of pregnancy and childbirth: WHO recommended interventions for improving maternal and newborn health. Geneva: WHO press; 2009. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2007/who_mps_07.05_eng.pdf. Accessed 13 December 2014.

Chunuan, S., Somsap, Y., Pinjaroen, S., Thitimapong, S., Nangham, S., & Ongpalanupat, F. (2009). Effect of the presence of family members, during the first stage of labor, on childbirth outcomes in a province hospital in Songkhla Province, Thailand. Thai Journal of Nursing Research, 13(1), 16–27.

Liamputtong, P. (2004). Giving birth in the hospital: Childbirth experiences of Thai women in Northern Thailand. Health Care for Women International, 25, 454–480.

Yuenyong, S., O’Brien, B. A., & Jirapaet, V. (2012). Effects of labor support from close female relative on labor and maternal satisfaction in a Thai setting. Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Neonatal Nursing, 41(1), 45–56. doi:10.1111/j/1552-6909.2011.01311.x.

d’Oliveira, A. F., Diniz, S. G., & Schraiber, L. B. (2002). Violence against women in health-care institutions: an emerging problem. Lancet, 359(9318), 1681–1685.

Liamputtong, P. (2005). Birth and social class: Northern Thai women’s lived experiences of caesarean and vaginal birth. Sociology of Health & Illness, 7(2), 243–270.

Whittaker, A. (1999). Birth and the postpartum in Northeast Thailand: contesting modernity and tradition. Medical Anthropology, 18(3), 215–242.

Crozier, K., Chotiga, P., & Pfeil, M. (2013). Factors influencing HIV screening decisions for pregnant migrant women in South East Asia. Midwifery, 29(7), e57–e63. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2012.08.013.

Langer, A., Horton, R., & Chalamilla, G. (2013). A manifesto for maternal health post-2015 Comment. Lancet, 318(9867), 601–602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60259-7.

CARE USA. (2012). Learning, sharing, adapting: innovations in maternal health programming. http://www.care.org/sites/default/files/documents/MH-2012-Learning-Sharing-Adopting.pdf. Accessed 3 November 2014.

United Nations Population Fund, International Confederation of Midwives, and World Health Organization (2014). The state of the world’s midwifery 2014: A universal pathway. A woman’s right to health. http://unfpa.org/webdav/site/global/shared/documents/publications/2014/SoWMy-Report-English-rev2.pdf. Accessed 3 November 2014.

Acknowledgments

Funding from Fulbright Scholarship, Thailand—United States Educational Foundation (Fulbright), Oxfam (UK); Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria; and Generosity in Action. Conclusions are those of the authors. Thanks to Sophie LeCoeur MD, PhD, co-investigator of Access to Care in Communities, Program for HIV Prevention and Treatment, Chiang Mai, Institute de Recherche pour le Developpement (IRD), France, and Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand (UMI 474-PHPT). Special thanks to the Hmong villagers who participated in research study, and William Ventres MD and Sonia Patten PhD for reading prior drafts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Culhane-Pera, K.A., Sriphetcharawut, S., Thawsirichuchai, R. et al. Afraid of Delivering at the Hospital or Afraid of Delivering at Home: A Qualitative Study of Thai Hmong Families’ Decision-Making About Maternity Services. Matern Child Health J 19, 2384–2392 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-015-1757-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-015-1757-3