Abstract

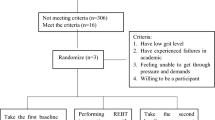

The present study examined the perceived credibility of two versions of Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT), specific and general, in the treatment of academic procrastination. A total of 96 university students rated treatment plans for their potential effectiveness which also included manipulations of two further variables: (1) the expertness level of the prospective counselor (expert vs. non-expert) and (2) whether the treatment was presented as an empirically supported treatment (EST) or non-empirically supported treatment (non-EST). The findings revealed a significant interaction between counselor expertness and EST status for the specific REBT rationale, but not for the general REBT rationale. As expected, participants’ credibility ratings of the specific REBT rationale were higher when a prospective counselor was described as expert as opposed to non-expert. However, this was only for the non-EST description. Contrary to predictions, when the specific REBT rationale was presented as an EST, treatment credibility was lower when counselor expertness was high compared to low. The findings have implications for clinical practice in respect to what information should be provided in treatment rationales and warrant further investigations into how specific REBT treatment is perceived.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Addis, M. E., & Carpenter, K. M. (1999). Why, why, why? Reason-giving and Rumination as predictors of response to activation and insight-oriented treatment rationales. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 55, 881–894.

Addis, M. E., & Jacobson, N. S. (2000). A closer look at the treatment rationale and homework compliance in cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24, 313–326.

Angle, S. S., & Goodyear, R. K. (1984). Perceptions of counselor qualities: Impact of subjects’ self-concepts, counselor gender, and counselor introductions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 31, 576–579.

Barak, A., & LaCrosse, M. B. (1975). Multidimensional perception of counselor behavior. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 22, 471–476.

Bernstein, B. L., & Figiolo, S. W. (1983). Gender and credibility introduction effects on perceived counselor characteristics. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 30, 506–513.

Bohner, G., Ruder, M., & Erb, H. P. (2002). When expertise backfires: Contrast and assimilation effects in persuasion. British Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 495–519.

Borkovec, T. D., & Castonguay, L. G. (1998). What is the scientific meaning of empirically supported therapy? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 136–142.

Borkovec, T. D., & Nau, S. D. (1972). Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 3, 257–260.

Burns, D. D. (1980). Feeling good: The new mood therapy. New York: William Morrow & Co.

Chambless, D. L., & Hollon, S. D. (1998). Defining empirically supported therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 7–18.

Chambless, D. L., & Ollendick, T. H. (2001). Empirically supported psychological interventions: Controversies and evidence. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 685–716.

Corrigan, J. D., Dell, D. M., Lewis, K. N., & Schmidt, L. D. (1980). Counseling as a social influence process: A review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 27, 395–441.

Devilly, G. J., & Borkovec, T. D. (2000). Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 31, 73–86.

Dryden, W., Dancey, C., & Goldsmith, P. (1990). The status of expectancy-arousal theory: Comparative credibility of systematic desensitization and rational-emotive therapy in the treatment for anxiety about study. Psychological Reports, 66, 803–809.

Dryden, W., David, D., & Ellis, A. (2009). Rational emotive behavior therapy. In K. S. Dobson (Ed.), Handbook of cognitive-behavioral therapies (3rd ed., pp. 226–276). New York: Guilford.

Dryden, W., Hurton, N., Malki, D., Manias, P., & Williams, K. (2008). Patients’ initial doubts, reservations and objections to the ABC’s of REBT and their application. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 26, 63–88.

Ellis, A. (1980). Rational-emotive therapy and cognitive behavior therapy: Similarities and differences. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 4, 325–340.

Ellis, A., & Knaus, W. J. (1977). Overcoming procrastination. New York: Institute for Rational Living.

Fox, S. G., & Wollersheim, J. P. (1984). Effect of treatment rationale and problem severity upon therapeutic preferences. Psychological Reports, 55, 207–214.

Goates-Jones, M., & Hill, C. E. (2008). Treatment preference, treatment-preference match, and psychotherapist credibility: Influence on session outcome and preference shift. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 45, 61–74.

Hardy, G. E., Barkham, M., Shapiro, D. A., Reynolds, S., Rees, A., & Stiles, W. B. (1995). Credibility and outcome of cognitive-behavioral and psychodynamic-interpersonal psychotherapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 34, 555–569.

Heppner, P. P., & Claiborn, C. D. (1989). Social influence research in counseling: A review and critique. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36, 365–387.

Heppner, P. P., Wampold, B. E., & Kivlighan, D. M. (2008). Research design in counseling. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Howell, D. C. (2007). Statistical methods for psychology (6th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

Hoyt, W. T. (1995). Antecedents and effects of perceived therapist credibility: A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 43, 430–447.

Kazdin, A. E., & Krouse, R. (1983). The impact of variations in treatment rationales on expectancies for therapeutic change. Behavior Therapy, 14, 657–671.

Kazdin, A. E., & Wilcoxon, L. A. (1976). Systematic desensitization and nonspecific treatment effects: A methodological evaluation. Psychological Bulletin, 83, 729–758.

LaCrosse, M., & Barak, A. (1976). Differential perception of counselor behavior. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 23, 170–172.

Lichtenberg, J. W. (1997). Expertise in counseling psychology: A concept in search of support. Educational Psychology Review, 9, 221–238.

Maddux, J. E., & Rogers, R. W. (1980). Effects of source expertness, physical attractiveness, and supporting arguments on persuasion: A case of brains over beauty. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 235–244.

Merluzzi, T. V., Banikiotes, P. G., & Missbach, J. W. (1978). Perceptions of counselor characteristics: Contributions of counselor sex, experience, and disclosure level. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 25, 479–482.

Morrison, L. A., & Shapiro, D. A. (1987). Expectancy and outcome in Prescriptive vs. Exploratory psychotherapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 26, 59–60.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Osarchuk, M., & Goldfried, M. R. (1975). A further examination of the credibility of therapy rationales. Behavior Therapy, 6, 694–695.

Pornpitakpan, C. (2004). The persuasiveness of source credibility: A critical review of five decades’ evidence. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34, 243–281.

Rokke, P. D., Carter, A. S., Rehm, L. P., & Veltum, L. G. (1990). Comparative credibility of current treatments for depression. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 27, 235–242.

Roth, A., & Fonagy, P. (2005). What works for whom? A critical review of psychotherapy research. London: Guilford Press.

Schmidt, L. D., & Strong, S. R. (1970). “Expert” and “inexpert” counselors. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 17, 115–118.

Shapiro, D. A. (1981). Comparative credibility of treatment rationales: Three tests of expectancy theory. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 20, 111–122.

Strong, S. R. (1968). Counseling: An interpersonal influence process. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 15, 215–224.

Strong, S. R., & Dixon, D. N. (1971). Expertness, attractiveness, and influence in counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 18, 562–570.

Strong, S. R., & Schmidt, L. D. (1970). Expertness and influence in counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 17, 81–87.

Tormala, Z. L., Briñol, P., & Petty, R. E. (2006). When credibility attacks: The impact of source credibility on persuasion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42, 684–691.

UCLA: Academic Technology Services, Statistical Consulting Group (2009). Statistical Computing. Retrieved 26 September 2009 from http://www.ats.ucla.edu/stat/spss/faq/threeway_hand.htm.

Wiggins, J. S. (1973). Personality and prediction: Principles of personality assessment. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Wollersheim, J. P., McFall, M. E., Hamilton, S. B., Hickey, C. S., & Bordewick, M. C. (1980). Effects of treatment rationale and problem severity on perceptions of psychological problems and counseling approaches. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 27, 225–231.

Wong, E. C., Kim, B. S. K., Zane, N. W. S., Kim, I. J., & Huang, J. S. (2003). Examining culturally based variables associated with ethnicity: Influences on credibility perceptions of empirically supported interventions. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 9, 88–96.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Specific REBT Treatment Rationale

A Psychological Treatment to Tackling Procrastination

Procrastination can be defined as putting off doing what is in your interests to do, at a time when it is in your interests to do it. As such, it is, by definition, self-defeating. While all students procrastinate at times some have a chronic problem with procrastination and require professional help. All forms of such help are based on an understanding of the reasons why people procrastinate.

What I will do here is to outline a treatment to helping people overcome procrastination. I want you to imagine that you have a chronic problem with procrastination and that you have decided to seek help for this problem. After you have read about the treatment you will be offered, I will ask you to answer some questions about it to gauge your opinion about the treatment.

The treatment is based on the idea that when you procrastinate, you are demanding or insisting that certain conditions exist before you get down to work and that you will put off working until these demanded conditions are met. Here are some common examples of such conditions, the demands that accompany them and the outcome of these demands. Please note that a demand is, by nature, a rigid attitude that you hold about the condition in question.

Condition | Demand (Rigid attitude) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

Comfort | “I must be comfortable before I start work” | Procrastination until I am comfortable |

Mood | “I must be in the mood before I start work” | Procrastination until I am in the mood |

Competence | “I must feel competent before I start work” | Procrastination until I feel competent |

Motivation | “I must be motivated before I start work” | Procrastination until I am motivated |

Immediate understanding | “I must understand what I have to do before I start to do it” | Procrastination until I have such understanding |

Pressure | “I must be under pressure before I start work” | Procrastination until I am under pressure |

Immediate gratification | “Faced with the choice of doing something that I enjoy or starting work I must do what I want to do” | Procrastination until I have done what I want to do |

Once your counselor has encouraged you to identify the conditions you believe have to exist before you start work, you will be helped to develop a healthier flexible attitude towards these same conditions. For example, if you demand pre-work comfort, you will be helped to see that while you might prefer to be comfortable before you start work, it is not necessary for you to be so. You can start work feeling uncomfortable and then see what happens. Typically what will happen if you start work feeling uncomfortable while holding this new flexible belief is that you will initially feel more uncomfortable, but then the discomfort will go down and soon pass as you get into your work.

The aim therefore is for you to adopt and apply a flexible attitude towards the conditions that currently believe have to exist before you start work. The following outlines the healthy flexible attitudes about the same conditions as those listed above and the outcome of holding these flexible attitudes.

Condition | Non-dogmatic preference (Flexible attitude) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

Comfort | “I would like to be comfortable before I start work, but this condition isn’t necessary” | Start work even though uncomfortable |

Mood | “I would like to be in the mood before I start work, but this condition isn’t necessary” | Start work even though not in the mood |

Competence | “I would like to feel competent before I start work, but this condition isn’t necessary” | Start work even though not feeling competent |

Motivation | “I would like to be motivated before I start work, but this condition isn’t necessary” | Start work even though not motivated |

Immediate understanding | “I would like to understand what I have to do before I start to do it, but this condition isn’t necessary” | Start work even though I do not understand what I have to do |

Pressure | “I would like to be under pressure before I start work, but this condition isn’t necessary” | Start work even though I am not under pressure |

Immediate gratification | “Faced with the choice of doing something that I enjoy or starting work I would like to do what I want, but this condition isn’t necessary” | Start work foregoing immediate gratification |

After you have been helped to identify the rigid attitude that underpins your procrastination and its flexible healthy alternative, the focus will be on encouraging you to see that your rigid attitude is false, illogical and unhelpful to you while the flexible alternative to this belief is true, logical and more helpful to you. In particular you will be reminded that your rigid attitude leads to procrastination, while your flexible attitude will help you to get down to work.

When you believe that a particular condition needs to exist before you start work (rigid attitude), you may well come up with a number of so called “reasons” to justify your procrastination. If you are honest with yourself, you will see that such “reasons” are really rationalisations and self-deceptions and that you can respond constructively to your own rationalisation and even start work while they come into your mind.

Once you have grasped these points and have gotten some practice at responding constructively to your rigid attitudes and rationalisations in the counseling session with the person helping you, you will then be helped to put your learning into practice at home using the following steps.

-

1.

Set a specific time when you are going to begin work

-

2.

If you do not start at the appointed time, identify the condition that you are insisting has to exist before you start and remind yourself that this condition is desirable, but not necessary.

-

3.

Start work in the absence of the condition even though it may feel strange and uncomfortable to do so and see what happens after a specified time.

-

4.

Identify and respond to any rationalisations you have given yourself not to start work and then start work. Do this even though the rationalisations may be in your mind to some extent.

Repeatedly acting in ways that are consistent with your flexible attitudes towards your work and not being seduced by your own rationalisations are the defining characteristics of this approach to dealing with procrastination.

Other Methods

After you have made progress at developing the relevant flexible attitudes and responding effectively to your rationalisations, you will be helped to address the following factors that may be involved in your procrastination problem.

-

Setting work-based goals and being goal focused

-

Developing better self-discipline

-

Improving your management of time

-

Choosing the best working environment for you

-

Improving your study skills

-

Reinforcing your study behavior

-

Chunking work periods and taking suitable breaks without returning to procrastination behavior

-

Getting exercise and developing good nutritional habits to protect you from lethargy

-

Getting a good night’s sleep to keep you fresh for work

However, this approach to tackling procrastination is based on the idea that none of the above useful practices will help you overcome your procrastination in the longer term without you:

-

(1)

first changing the rigid attitudes that I have already discussed to their flexible alternatives and

-

(2)

then changing the rationalisations that support your rigid attitudes and the procrastination that stems from them.

Once you have made good headway at doing these two things, you will be able to make longer-term use of these other methods of tackling procrastination.

General REBT Treatment Rationale

A Psychological Treatment to Tackling Procrastination

Procrastination can be defined as putting off doing what is in your interests to do, at a time when it is in your interests to do it. As such, it is, by definition, self-defeating. While all students procrastinate at times some have a chronic problem with procrastination and require professional help. All forms of such help are based on an understanding of the reasons why people procrastinate.

What I will do here is to outline a treatment to helping people overcome procrastination. I want you to imagine that you have a chronic problem with procrastination and that you have decided to seek help for this problem. After you have read about the treatment you will be offered, I will ask you to answer some questions about it to gauge your opinion about the treatment.

The treatment is based on the idea that procrastination stems from a number of factors, all of which will be considered in counseling sessions. Before I introduce these factors and discuss how they would be addressed, I want to make the important point that your counselor will carry out a thorough assessment of your procrastination problem and the factors that maintain it before planning with you a tailored treatment to helping you to deal with your procrastination problem. Having said that, here are the nine areas that will be considered in the treatment that you will be offered.

Setting Goals and Being Goal Focused

People who procrastinate tend to easily lose sight of their goals with respect to the work that they put off. Here, you will be helped to set work-related goals and develop reasons for your goals. You will be helped to keep these reasons to the forefront of your mind and particularly to rehearse them when deciding whether to work or procrastinate.

Dealing with Emotional Factors and the Negative Thoughts and Attitudes that Underpin Them

People who procrastinate often do so because of emotional factors such as fear of failure. If this is the case with you, you will be helped to identify the negative thoughts that underpin your anxiety-based procrastination and will learn constructive alternatives, thoughts that will lead you to study rather than procrastinate.

Furthermore, you will be helped to identify underlying unhelpful attitudes that render you vulnerable to procrastination and will learn constructive attitudes in their stead. Thus, if you think that your worth as a person is based on how well you do a piece of work, you will learn how to detach your worth from your performance.

Developing Better Self-Discipline

People who have a procrastination problem have a problem with self-discipline. They tend to do things that are not in their longer-term interest and, by definition, don’t do what is in their self-interest. If lack of self-discipline is a factor in your procrastination, you will be helped to address this problem as it pertains to developing good work habits. In particular, you will be helped to identify the thoughts that lead you to engage in pleasurable pursuits rather than getting down to work and in their stead you will be encouraged to think in ways that help you to resist temptation and start work.

Improving Your Management of Time

People who procrastinate do not utilise their time very well. They think they have more time to do a task than they actually have. Also, when they do eventually decide to get down to work, they waste time by doing things like organising their desk and study materials. If time management is a problem for you, you will be helped to do such things as

-

Analysing a piece of work and deciding realistically how much time it would take and devoting extra time to it in case of unexpected eventualities

-

Keeping a time management diary so that you can see how you actually use time and on the basis of this how you can use your time more effectively

Identifying the Working Environment that Suits You Best

People who procrastinate tend not to consider the environment in which they study. Some people work better in a quiet environment while others work better with some background noise. Some people work better alone, while yet others concentrate when others are present. You will be helped to identify the environment in which you work best and you will be encouraged to work in this environment even though it may seem strange to others (e.g., in a coffee bar of a busy train station).

Improving Study Skills

People who procrastinate frequently lack good study skills and if this applies to you, you will be helped to identify skills that you might improve on and be helped to do so. Here is a sample of such skills:

-

Using different reading strategies for different purposes

-

Picking out key points in reading material

-

Making useful notes while reading

-

Planning essays and other written assignments

-

Putting material into your own words

The argument is that once you have improved your study skills then you will be less inclined to procrastinate.

Reinforcing Study Behavior

One of the most robust findings in human psychology is that behavior is more likely to occur when it is reinforced. The problem with many people who procrastinate is that they tend to opt to have their reinforcement before doing their work rather than work and then reinforcing themselves for it. So, if this applies to you will be encouraged to set realistic work targets and reinforce yourself when you have met these targets. Conversely, you will be encouraged to refrain from engaging in rewarding activity until you have achieved your targets.

Chunking Work Periods and Taking Suitable Breaks

People who procrastinate leave things to the very last minute before getting down to work. When they eventually get down to work they usually have to work long hours without taking a break. Thus, they tend to have two positions: procrastination and long unstinting work periods. When people procrastinate they do so because (a) they associate work with long periods of unremitting tedium and (b) they procrastinate to avoid such associations.

If this applies to you, you will be helped to making new associations with work by studying in manageable chunks (as defined by you) and taking suitable breaks from work.

Getting into and Keeping Yourself in the Best State for Sustained Study

When you have to engage in a prolonged period of study, it is easy to overlook the importance of factors that may impact on your studying behavior like physical and mental fitness. Since studying involves being alert, it is important that you consider ways of getting yourself into the best state to sustain your mental alertness. Otherwise you will feel tired and lethargic, states which will make it easy for you to continue to procrastinate. You will be encouraged to consider two areas here:

-

Getting exercise and developing good nutritional habits to protect you from lethargy

-

Getting a good night’s sleep to keep you fresh for work

If you need help in either or both of these areas, then this will be provided to you. Thus, you will be: (a) helped to construct and follow a realistic physical exercise programme; (b) given dietary and nutritional advice and (c) helped to develop and implement good sleep habits.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dryden, W., Sabelus, S. The Perceived Credibility of Two Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy Rationales for the Treatment of Academic Procrastination. J Rat-Emo Cognitive-Behav Ther 30, 1–24 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-010-0123-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-010-0123-z