Abstract

Objectives

The paper explores the effects of electronic monitoring (EM) on young offenders’ educational outcomes and contributes to the evaluation of EM as a non-custodial sanction with a new outcome measure.

Methods

The study is based on a natural experiment exploiting a reform in Denmark in 2006 introducing electronic monitoring to all offenders under the age of 25 with a maximum prison sentence of 3 months. Information on program participation is used to estimate instrument variable models in order to assess the causal effects of EM on young offenders’ educational outcomes. The empirical analyses are based on a comprehensive longitudinal dataset (n = 1013) constructed from multiple official administrative registers and including a high number of covariates.

Results

The EM-program increases the completion rates of upper secondary education by 18 % points among program participants 3 years post-release. The EM-program includes house arrest under electronic surveillance, labor market or education participation, unannounced drug and alcohol tests and a crime preventive program. It is not possible to separate the treatment effects of the different program elements in the empirical analyses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the early 1980s, the use of electronic monitoring (EM) for offenders has spread to penal systems across the world (Nellis et al. 2013). More than 500,000 people in the United States and Europe had been electronically monitored by 2010 (Di Tella and Schargrodsky 2013), and nearly 200,000 EM units are used in the United States each year (Payne, 2014). In times with growing prison populations, EM has been introduced in many Western countries as a substitute for imprisonment or as part of an early release program in order to reduce expenditures in the prison system (Renzema and Mayo-Wilson 2005). Although EM has been implemented in many different legal systems over the last three decades, there is still a lack of empirical knowledge on the effects of this non-custodial alternative to imprisonment (Andersen and Andersen 2014).

Non-custodial sanctions such as probation, community service and electronic monitoring typically lack random assignment, because offenders with the most serious records and the highest risk of re-offending are often found non-eligible and placed in confinement. This makes it difficult to determine the causal effects of these types of sanctions, as selection into the programs often depends on the expected outcome (for example, re-offending). Previous reviews of non-custodial sanctions and electronic monitoring have only identified a few quantitative studies that applied methodologically sound designs in order to evaluate the effects of alternative sanctions (Renzema and Mayo-Wilson 2005; Villettaz et al. 2006). The evaluations of EM-programs included in these reviews did not find significant effects of electronic monitoring on recidivism rates (e.g. Bonta et al. 2000; Finn and Muirhead-Steves 2002). However, these small-scale evaluations have since been criticized for methodological shortcomings (Di Tella and Schargrodsky 2013; Marklund and Holmberg 2009), and recent studies of EM have identified positive effects on participants’ subsequent criminal outcomes. Marklund and Holmberg (2009) evaluate the Swedish EM-program using matching methods and document lower recidivism rates among offenders with early release on electronic monitoring. More recent studies have done causal inference by applying different natural experimental designs to address selection bias. Di Tella and Schargrodsky (2013) use the random assignment of judges in Argentina to compare offenders serving in prison with offenders serving with electronic monitoring, and they document significant negative effects on re-arrest rates between 11 and 16 % points. A study of early EM releases from prisons in England using a regression discontinuity design finds a reduction in the probability of re-arrest of ex-prisoners between 20 and 40 % within 2 years (Marie 2015). Finally, two studies exploit the reforms that introduced and extended the use of electronic monitoring in Denmark and document negative effects on recidivism (Jørgensen 2011) and positive effects on subsequent labor market outcomes (Andersen and Andersen 2014).

This brief survey of recent studies on electronic monitoring reflects a general trend in the literature evaluating non-custodial sanctions. The literature typically has a strong focus on recidivism, which leaves a gap when it comes to measures of rehabilitation (Killias et al. 2010). Although a classic argument for substituting short-term prison sentences with non-custodial sanctions is the damaging effects of imprisonment on offenders’ social networks and integration into society, rehabilitation outcomes such as employment, income, education and family relations are rarely measured and evaluated (Villettaz et al., 2006). Furthermore, little is known about the effects of alternative sanctions on young offenders’ future outcomes. Studies of juvenile court involvement and incarceration have documented substantial negative effects on educational attainments (Aizer and Doyle 2015; Hjalmarsson 2008; Sweeten 2006). Therefore, it is important to obtain knowledge about whether non-custodial sanctions like EM interrupt young adults’ educational course to a lesser extent. The grounds for changing the Danish legislation in 2006 and giving young offenders with short-term prison sentences the opportunity to serve with electronic monitoring was actually the argument of maintaining labor market participation and educational enrollment (Sorensen and Kyvsgaard 2009). The scope of this paper is to contribute with new knowledge about non-custodial sanctions by comparing the effects of imprisonment and electronic monitoring on young offenders’ educational outcomes.

Electronic monitoring is a less intrusive type of punishment compared to custodial sanctions,Footnote 1 and criminological theoretical perspectives provide diverse expectations regarding the impact on offenders’ future outcomes. The theories on deterrence argue that the severity of punishment affects the offenders’ subsequent criminal behavior, because the experience of imprisonment changes the offenders’ perception of sanctions (e.g., Becker 1968; see reviews of deterrence studies: Nagin 1998, 2013; Nagin et al. 2009). Hence, the deterrence perspective would predict higher reoffending rates among offenders serving with EM, compared to offenders serving time in prison. A less severe punishment would have a lower self-deterrent effect, and offenders who experience incarceration would be more likely to desist from criminal acts.Footnote 2 Offenders serving with EM would therefore have a higher probability of reoffending, and thus be more likely to drop out of education and achieve lower educational outcomes due to subsequent imprisonment. On the other hand, theories on social learning and peer effects point to lower re-offending rates among offenders serving with EM with reference to the interactions with other criminals, the training of criminogenic skills and the hardening of offenders in prison. Within this framework, exposure to deviant peers is assumed to prompt higher levels of delinquency due to deviant attitudes and norms, direct modeling and indirect reinforcing effects (see e.g., Akers 1998; Mcgloin 2009). Empirical studies have documented causal peer effects and specialization among inmates (e.g. Bayer et al. 2009; Damm and Gorinas 2013; Stevenson 2014), which suggests that offenders in house arrest with electronic surveillance who have fewer interactions with other criminals and more contact with pro-social peers (like family) would be less likely to reoffend. In regards to educational outcomes, this would imply that offenders serving with EM with lower recidivism rates are less likely to drop out and have a higher chance of achieving better educational results. Additionally, in EM-programs including a provision to attend school, contact with pro-social classmates, instead of criminal inmates, can increase the chances of young offenders continuing in the school system.

The purpose of the present study is to examine the effects of electronic monitoring by looking at a new outcome measure, education, which has great significance to the young offenders’ future trajectories. Previous research has documented a negative correlation between education and delinquency (e.g., Farrington et al. 1986; Gottfredson 1985; Lochner and Moretti 2004), as individuals with higher educational attainments are less likely to be involved in criminal activities. Furthermore, a large number of empirical studies have documented negative effects of dropping out of secondary education on subsequent criminal outcomes (see review in Rumberger 2011). Education is not only important to criminal outcomes, but plays a significant role in determining individual life-course outcomes, such as health, income and employment (see e.g., reviews by Card 1999; Oreopoulos and Salvanes 2011). Thus, the completion of upper secondary education is important to all young adults to secure future life outcomes, and especially to young offenders in order to reduce the risk of reoffending, overcome the mark of a criminal record, enhance the chance of entering the labor market and obtain a legitimate income.

Research Design and Methodology

In Denmark, serving with electronic monitoring has gradually been introduced as a non-custodial sanction over the last decade from 2005 to 2013.Footnote 3 Contrary to many other countries, electronic monitoring in Denmark is a voluntary program offered by the Department of Prison and Probation Service (DPPS) as a way of serving a prison sentence. This implies that the Danish program is an alternative to imprisonment and not part of the probation program or other early release programs. Thus, offenders who meet the formal criteria regarding sentence length (and age), who are not incarcerated and do not have unserved prison sentences receive a letter informing them about the opportunity to serve the prison sentence at home under intensive surveillance and control.

Offenders who choose to apply for the EM-program must fulfill a number of requirements in order to get approved for the program by the DPPS. First of all, they have to hold a permanent address and obtain consent from family members, spouse or other individuals over the age of 18 living at the address. Second, they must participate in the labor market or be enrolled in an educational program. Third, offenders who have previously served with EM are disqualified if re-sentenced (incl. suspended sentences) within the last 2 years. Finally, the DPPS can reject the application to the EM-program with reference to personal circumstances (e.g., intensive drug or alcohol abuse). Prior studies of the Danish EM-program have shown that among young offenders offered the chance to serve with electronic monitoring, 30 % did not apply to the program, and 9 % had their applications rejected by the DPPS (Jørgensen 2011).Footnote 4

The Danish EM-program includes house arrest under electronic surveillance with an ankle bracelet and a fixed schedule for leaving and returning to the house within a time limit of plus/minus 5 min. The program participants are obliged to attend work or school (minimum of 20 h a week), and they are subject to unannounced visits from DPPS workers, including tests for drug or alcohol use. Finally, they attend a mandatory crime preventive program organized by DPPS. If the offenders violate any of these terms, the permit to serve under house arrest will be suspended, and he/she will serve the rest of the sentence in prison.

A methodological note should be made in regard to the program content; due to the fact that the Danish EM-program includes several elements besides electronic surveillance, it is not possible to distinguish between the effects of electronic monitoring and other parts of the program in the empirical analyses. The program conditions and content are of great importance when comparing custodial and non-custodial sanctions, because they define the fundamental characteristics of the comparison, and thus the generalizability of the findings (Mears et al. 2015; Nagin et al. 2009). I compare participants in the EM-program who are treated with all of the different program elements (described above) to offenders serving their sentence in prison. In a Danish context, a custodial sanction of a maximum of 3 months sentenced to offenders over the age of 18 typically entails confinement in an open prison facility.Footnote 5 In the open prisons, the prisoners can leave the facility during the day to attend school or work. The assignment of offenders to facilities by the DPPS relies on sentence length, age, distance to residential address (i.e. to maintain enrollment in education) and prison capacity (Damm and Gorinas 2013). Although offenders serving in open prisons officially have the opportunity to continue their educational program during their imprisonment, this can be difficult to do in practice. Prison facilities are, for example, often located in the countryside, and the distance to the educational institutions by public transportation can therefore be very long.

The Natural Experiment

Evaluating the causal effects of serving a sentence with electronic monitoring requires a treatment group and a control group that are identical in all characteristics besides the type of sanction. This requirement makes it difficult to determine the causal effects of new forms of sanctions such as probation, community service or electronic monitoring, as they are often introduced without a controlled trial setup. Alternative sanctions typically lack random assignment, as offenders with the most serious records are found non-eligible to serve with e.g., electronic monitoring, and are thus placed in confinement. These circumstances cause selection problems, and together with the fact that the EM-programs are often restricted to low-risk offenders, this makes it difficult to evaluate the program effects (Di Tella and Schargrodsky 2013).

In this study, I exploit a natural experiment and apply instrumental variable estimations to address these methodological challenges and evaluate the causal effects of EM on ex-offenders’ educational outcomes. Specifically, I analyze the Danish reform of 2006 introducing EM to offenders between the ages of 15 and 25 with a maximum prison sentence of 3 months, and evaluate a case with an EM-program offered to young moderate risk offenders with short custodial sentences who would otherwise be incarcerated.Footnote 6 The EM-reform constitutes a natural experiment in which young offenders with short-term prison sentences are ‘treated’ with different types of sanctions before and after the reform.Footnote 7 The setup makes it possible to compare educational outcomes between the treatment group: offenders sentenced April 21st 2006 to April 21st 2009 and the historical control group: offenders sentenced April 21st 2003 to April 20th 2006. The overall design of the study is illustrated in Fig. 1.

When applying a natural experimental design and including a historical control group, it is important to consider any historical changes that can affect the comparability between the two groups. In regards to the justice system, changes in the penal code or the judges sentencing practice that entail short prison sentences in new types of cases could potentially bias the results if the characteristics of the offenders with a prison term under 3 months systematically changed over the period 2003–2009. The introduction of new alternative sanctions restricted to convictions of a certain length could affect the judges’ sentencing behavior. However, this does not appear to be the case in Denmark in relation to the EM-program, since the overall distribution in sentence length did not change around the EM-reform (Andersen and Andersen 2014), and there are no substantial differences in types of crimes or sentence lengths between the two groups of offenders convicted before and after the reform (see Table 1). Hence, there is no evidence of the introduction of the EM-program as an offer to young offenders leading to systematic changes in the judges’ sentencing behavior, either towards lower or higher prison terms, in the years 2006–2009. This suggests that the reform, which introduces a new form of non-custodial sanctions and changes the individuals’ likelihood of serving with EM from 1 day to the next, is unrelated to the characteristics of the offenders.

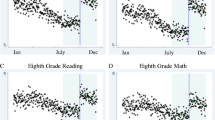

At the same time, it is important to look at reforms and other changes in the educational system that could affect the dropout and completion rates of the control and treatment groups differently during the observed period (2003–2009). If there was a time trend, for example, a general gradient decrease in the dropout rate over the 6 year period, then the estimated treatment effects could be biased. The present study focuses on upper secondary education, which is divided into two main tracks in Denmark: vocational education and training and general upper secondary education.Footnote 8 The official statistics show stable completion rates in Denmark from 2003 to 2009 in both vocational and general upper secondary education. To investigate whether this general trend also applies to the study sample, I compare the educational outcomes of the control and treatment groups prior to conviction. Figure 2 shows the percentage of young offenders who are not enrolled in and have not completed upper secondary education at five different time points prior to conviction and five different time points after release from prison or the EM-program. Two years before conviction, about 40 % of the offenders are not enrolled in and have not completed upper secondary education. This percentage falls gradually up until conviction, when the restrictions of the study sample imply that all offenders are enrolled in upper secondary education at the time of conviction (cf. sample description in “Data” section). There are no significant differences between the treatment and control groups prior to conviction, which suggests that the outcome measure is not influenced by historical changes.

Percentage of young offenders with short-term prison sentences who are not enrolled in and have not completed upper secondary education at five time points prior to conviction and five time points after release. Data source: Administrative register data from Statistics Denmark and the Department of Prison and Probation Service for Danish offenders (age 18–25) sentenced to short-term prison sentences in 2003–2009

Data

The empirical analyses use a longitudinal dataset constructed from multiple administrative registers provided by Statistics Denmark and matched by a unique personal identifier. This dataset enables me to draw a full sample of all 8741 Danish offenders 15–25 years old who are sentenced to a prison sentence of a maximum of 3 months from April 21st 2006 to April 21st 2009. In the Danish legal system, special sentencing and sanctioning options apply to offenders between the ages of 15 and 18, which implies that they are not placed in regular prison with adult inmates, but confined at special secured institutions.Footnote 9 For this reason, I restrict the analyses to offenders 18–25 years old, given that the sample of young offenders below the age of 18 (n = 413) is too small to estimate separate models for this group. Furthermore, to ensure that the comparison of sanction types is limited to electronic monitoring versus imprisonment, I exclude offenders who are ‘fuzzy’ treated (n = 264), as they are sentenced to both imprisonment and community service.

I use data from the DPPS to identify offenders in the treatment group who fulfill the formal criteria and are offered to serve with electronic monitoring by letter from the DPPS. To match this group of offenders, I use the detailed register data to extract a historical control group conditioned on the same formal criteria that apply to the treatment group. These restrictions of the two groups reduce the sample to a total of 5230 individuals who fulfill the formal criteria to serve with EM. In a final step, I reduce the dataset to the 1013 offenders who are enrolled in education at the time of conviction. This step is important in order to ensure that the educational outcome is not influenced by the offenders’ anticipation of treatment, because the approval by the DDPS to serve with EM requires participation in the labor market or educational enrollment. The enrollment in upper secondary education is measured at the day of conviction, as this time point also defines whether the offender is eligible for the EM-program or not (i.e. convicted before or after the reform).

In order to analyze the educational outcomes, I exploit the longitudinal register data and follow the offenders for 3 years after their release from prison or the EM-program. At the time of the study, this is the maximum follow-up period for which educational records are available for all six cohorts of offenders convicted 2003–2009.Footnote 10 The register data holds information on all entries in the Danish educational system, and I measure the outcome variable (enrolled, dropped out, completed) at six different time points: 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, 30 and 36 months after release. The outcome variable is measured relative to the offender’s unique release date, and it allows for re-entry to the educational system between the six different time points. The descriptive analyses in the section “Empirical Findings” report all three outcome categories: enrolled, dropped out and completed upper secondary education, and they also include a survival analysis of the time to completion. The regression analyses solely focus on completed upper secondary education as the outcome measure, given that the initial results do not reveal significant differences in the enrollment rates of the treatment and control groups. Completion of upper secondary education is especially important to the group of young offenders in this study, as 91 % of them are enrolled in the vocational program, which qualifies them to enter skilled employment in the labor market (such as e.g., carpenter, blacksmith, electrician or hairdresser) directly after graduating.

The use of register data makes it possible to test the comparability of the historical control group and the treatment group with a high number of observables. Thus, I combine multiple administrative registers to include a wide range of different control variables on demography, type of sentence, crime and educational history. The first three types of variables are included with reference to prior research that enhanced the importance of including information on conviction offense type, criminal history and demography (age, sex and race) in studies comparing different forms of sanctions (Nagin et al. 2009). In addition to these classical covariates in criminological studies, I also include information on the offenders’ prior educational attainment to ensure that the treatment and control groups do not differ substantially pre-treatment in observables linked to the outcome measure. Table 1 shows summary statistics for these variables, including test of the mean tendencies between the treatment and the control groups. The descriptive statistics for the two groups only reveal small differences in the type of offense, crime and educational history between the treatment and the control groups.Footnote 11

Estimation Method

The study samples consist of a total of 1013 offenders sentenced to a prison term of a maximum of 3 months who fulfill the formal requirements to serve with electronic monitoring. The control group includes 570 offenders convicted in 2003–2006 (prior to the reform) who all served their sentences in prison. As described previously, electronic monitoring is a voluntary program in Denmark, and participation in the program requires the offender to apply and obtain approval from the DPPS. This program feature implies that the treatment group includes 278 individuals who applied for the EM-program, got approved by the DPPS and served their sentence with EM and 165 offenders who did not apply for the program or did not receive permission to serve with EM, and therefore, served the sentence in prison (see Table 2).

This empirical setup with a ‘divided’ treatment group resembles a classic example of non-compliance to treatment in an experimental study, where the intended treatment is randomly assigned, but the delivered treatment is not randomly distributed, because some of the participants in the treatment group do not comply with the assigned treatment. In this study, I argue that the intended treatment, offering offenders the EM-program, is randomly assigned due to the reform in 2006 (as discussed in “The Natural Experiment” section), whereas the delivered treatment, serving with EM, is not randomly assigned. Quite the contrary, the delivered treatment relies on the offenders’ application to the EM-program and the permission of the DPPS, and is, therefore, expected to be determined by (unobservable) characteristics of the offender, such as drug abuse, motivation and social network. Put in other terms, the offenders who end up serving under house arrest with electronic monitoring are selected members of the treatment group and are most likely to be offenders with the lowest risk of recidivism and the highest chances of completing their education, even if they were not in the EM-program. These selection issues, which are caused by the offenders’ self-selection into the program, and the non-random allocation of permissions by the DPPS, underline the importance of applying appropriate estimation techniques to address selection and omitted variable bias. This is important, as the fundamental assumption of exogeneity in the linear regression model is violated when the unobserved characteristics of the offenders (such as motivation, self-control or drug abuse) are correlated with both the likelihood of serving with EM (X) and educational outcomes (Y). This means that if we estimate the treatment effects with simple OLS-regression models, the regression estimates would be biased by confounding, and causal interpretation is not possible (Angrist 2006).

One strategy to address the methodological issues is to estimate Intention-To-Treat (ITT) models. Here, the researcher compares outcomes between the control group and the group assigned to treatment; in this case, all 443 individuals in the treatment group who were offered to serve with EM (regardless of whether they actually served with EM or in prison). This way, you make a ‘conservative’ evaluation of the treatment effects as you compare the outcomes of the non-treated control group to the outcomes of a mixed group of treated and non-treated offenders. Hence, the ITT-models will, by definition, underestimate the effects of treatment due to the non-compliance (Angrist 2006; Bushway and Apel 2010).

A second strategy is to estimate an Instrument Variable (IV)-model that addresses the selection issues and takes the compliance rate into account. The IV-strategy allows you to exploit the random assignment of the intended treatment to estimate the causal effects of the delivered treatment (Angrist 2006).Footnote 12 In this setup, I use the EM-reform in Denmark in 2006 as an instrument (Z) for whether the offender served with electronic monitoring or served in prison. The EM-reform is highly correlated with the endogenous variable (serving with EM), but unrelated to the enrollment/completion rates from upper secondary education (see “The Natural Experiment” section). I estimate two stage least square (2SLS) regression models to evaluate the causal effects of electronic monitoring on the offenders’ subsequent educational outcome, using the reform, which introduces random allocation to the EM-program (intended treatment) as an instrument of serving with EM (delivered treatment). The 2SLS regression model can be written as follows:

where \(X_{i}\) is the delivered treatment variable, served with EM or not for individual i., \(Z_{i}\) is the instrument variable, convicted before or after the reform for individual i, \(Y_{i}\) is the educational outcome for individual i, \(\omega_{i}\), \(\varepsilon_{i}\) and \(\mu_{i}\) are the error terms in the respective models.

The first stage model estimates the correlation between the instrument (Z) and the endogenous variable (X), and the fitted values from the first-stage model (\(\hat{X}_{\text{i}}\)) are used in the second-stage model as an instrument put in the place of the endogenous variable. In a model with a dummy variable of the delivered treatment (1 for serving with EM and 0 for serving in prison), the first stage model measures the compliance rate, in this case, the proportion of the population that serves with electronic monitoring. The second stage model estimates the 2SLS coefficient, and in models with one-sided non-compliance,Footnote 13 this estimate can be interpreted as the average causal effect of treatment to the treated (ATET) (Angrist, 2006). In this study, the ATET-effect applies to young offenders (18–25 years old) with short-term prison sentences who are enrolled in education at the time of conviction and who are in the EM-program, and it reflects the difference between the average educational outcomes of the offenders serving with EM and the average educational outcomes of the imprisoned offenders. The 2SLS estimate is a rescaling of the ITT-effect by the compliance rate, when the IV-model includes one endogenous variable and a single instrument (Angrist 2006). All in all, the IV-method is a simple and valuable technique to address selection bias in both experimental and quasi-experimental studies (Angrist 2006; Bushway and Apel 2010).

It is important to note that I estimate linear regression models (and not probit or logit models), even though the outcome measure and instrument variable are discrete. The linear regression estimates are identical to marginal effects in non-linear models when applied to a saturated regression model, only including dummy variables on the right hand side (Angrist 2006; Angrist and Pischke 2009). Furthermore, the causal interpretation of the 2SLS estimates is not affected by the nonlinearity of the discrete instrument variable or the outcome measure (Angrist 2001, 2006). The 2SLS regression model is therefore preferable to other more complex estimation methods, such as 3SLS models.

Empirical Findings

In order to evaluate educational outcomes after serving with electronic monitoring, I look at six different time points after the offenders’ release from either prison or the EM-program. There are no significant differences between the treatment and control groups at 3, 6, or 12 months after release (see Table 3). But, 18, 24, 30 and 36 months after release, the percentage of offenders who completed upper secondary education is significantly higher in the treatment group. In both the treatment and the control group, about 20 % of the offenders dropped out of the educational system from the time of conviction, during the time served and within the first 3 months post-release. This suggests that the results found by Aizer and Doyle (2015) in their study of juvenile incarcerations do not apply to a Danish case with young offenders enrolled in upper secondary education. Aizer and Doyle (2015) document negative effects of short periods of incarceration on the likelihood of returning to school among juveniles, which are potentially caused by formal hindrances in the school system. However, in this study, there are no significant differences between the offenders serving in prison and the offenders serving with EM within the first 12 months after release. So, if discrimination also exists in the Danish educational system, it seems to affect both groups of offenders in this study.

Figure 3 shows the time to completion of upper secondary education, measured in days from the time of conviction. To ensure that differences between offenders serving in prison and offenders serving with EM do not simply reflect a delay in the completion time caused by the confinement period, the number of days spent in prison is excluded from the exposure time in the survival plot. The results support the previous findings, as there are no differences in the probability of completing upper secondary education in the first years after conviction, and the treatment group has significantly higher completion rates compared to the control group in the longer run.

Survival plot: time to completion of upper secondary education from conviction. Data source: Administrative register data from Statistics Denmark and the Department of Prison and Probation Service for Danish offenders (age 18–25) sentenced short-term prison sentences in 2003–2009. Note: Wilcoxon Test, p value: 0.003 and Log-Rank Test, p value 0.001

The descriptive results show similar educational outcomes for the young ex-offenders with short prison sentences within the first year after conviction/release and higher educational outcomes for the treatment group in the longer run. However, these simple comparisons of educational outcomes between the treatment and control groups could underestimate the actual effects of the EM-program compared to imprisonment. About 37 % of the offenders in the treatment group were offered the chance to participate in the EM-program, but served in prison (see Table 2). Hence, the comparisons do not reflect the ‘real’ differences between offenders serving with EM and offenders serving in prison, but can be characterized as descriptive intent-to-treat estimates. In the next section, I present the results from the IV-regression models that estimate the causal effects of the EM program, taking both the selection of participants for the EM-program and the compliance rate in the treatment group into account.

Results from IV-Estimations

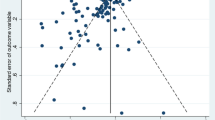

The IV-method estimates two regression models simultaneously: the first and second stage regression models. Table 4 shows the results of two first stage models with and without covariates. The first stage regression models evaluate the effects of the intended treatment, offered to serve with EM (convicted after the reform) on the delivered treatment, served with EM. The results show large and significant first stage effects of the instrument. The introduction of covariates does not influence the results, which suggests that the second stage estimations (presented in Table 5, Models C) can be interpreted as the average causal effect of serving with electronic monitoring, because individual offender characteristics do not appear to influence the likelihood of the offender being convicted before or after the EM-reform. Furthermore, only a few of the observed individual characteristics (demography, criminal history and prior educational records) contribute significantly to explain which offenders eventually serve with EM (see all results for the covariates in the first stage model in Table 6 in the “Appendix”).

Table 5 shows the results from three different types of regression models for the completion of upper secondary education, measured 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, 30 and 36 months after release. Models A are simple OLS regression models, Models B are Intent-To-Treat regression models and Models C are the second stage regression models. The 2SLS regressions (Models C) show the average differences in the completion rates of upper secondary education between offenders serving with EM and offenders serving the sentence in prison. There are no significant differences 3, 6 and 12 months after release, which points to a short-term retention effect among offenders from the EM-program, leading to higher completion rates in the longer run. After 18 months, 2SLS estimates show significant differences between the two groups, and the EM-program increases the completion rates from upper secondary education by 11.2 % points 1.5 years after release and 17.8 % points 3 years after release. Thus, there is a positive effect of the EM-program on the educational outcome of young offenders with short custodial sanctions, as a higher percentage of the offenders serving with electronic monitoring complete upper secondary education post-release.

Table 5 also includes the results of simple OLS-models and ITT-models for comparison. First, the simple OLS regressions (Model A) identify significant differences at 4–6 time spells and overestimate the effects of the EM-program, when compared to the results from the 2SLS-models. Second, the ITT-models take selection into account by comparing the control group with the total treatment group (offered to serve with EM). The results resemble the 2SLS-estimations by identifying a significant difference 1.5, 2, 2.5 and 3 years after release. But the ITT-estimates are too low, relative to the 2SLS-estimates, because only 63 % of the offenders in the treatment group served with EM, and this drives the estimated effects downwards. The 2SLS-estimates are a rescaling of the ITT-effects by the compliance rate, and they identify the causal program effects of electronic monitoring, which otherwise would have been underestimated by applying ITT-estimation techniques.

Sensitivity Analyses

The robustness of the results from the empirical analyses is tested with different specifications of the study sample. First, the result from the first stage model with covariates suggests that matching the group of offenders serving with EM to controls based on observable characteristics would be difficult. Instead of applying Propensity Score Matching to estimate the treatment effects of serving with EM, I use the setup to refine the initial selection of the treatment and control groups, and subsequently, estimate 2SLS models to take selection to the EM-program into account. Based on the results from a propensity score model, I restrict the sample (n = 1013) to cases with common support (n = 1006) and then estimate 2SLS-models with this sub-sample. The results from this sensitivity analysis are very similar to the reported findings (see Table 7 in the “Appendix”). This is, however, not surprising, as the calculation of the propensity score only leads to the exclusion of 7 observations from the control group. These findings support the claim that the construction of the control group based on the formal criterion to serve with EM provides a reliable match to the treatment group on observable characteristics. Moreover, the results support that the EM-reform constitutes a natural experiment creating variation in the offered sanction type to young offenders with a prison sentence exogenous to individual characteristics.

Second, some offenders in the treatment group broke the terms of the EM-program and ended up serving the rest of their sentence in prison. This group experienced both electronic monitoring and prison, and to make sure that these ‘double treated’ offenders do not affect the results, I estimate the 2SLS-models without these 29 individuals. The results are again very similar to the reported findings (see Table 8 in the “Appendix”). Third, if offenders serving in prison cannot continue their educational program during incarceration, this may delay their completion of upper secondary education. To test whether the findings could be influenced by the confinement time of the control group, I have estimated the 2SLS-models supplying three extra months to complete upper secondary education to the control group. Even with the extended follow-up periods for the control group, the significant differences between offenders serving in prison and offenders serving with EM still exist and the effect sizes are very similar to the reported finding (see Table 9 in the “Appendix”).

Finally, recent discussions regarding the evaluation of sanctions have highlighted the importance of investigating heterogeneous treatment effects, as interventions may have varying effects across different groups of offenders (Mears et al. 2015). In this study, the sample size was, however, too small (resulting in large standard errors) to analyze heterogeneous effects with separate models for different subpopulations (e.g., divided by age, education length, prison conditions or prior prison history). In future studies, this type of analysis will be relevant in order to assess, for example, which groups of offenders benefit the most from serving with EM.

Conclusion and Discussion

The results of the empirical analyses reveal significant differences between offenders serving with electronic monitoring and offenders serving in prison when we look at their educational outcomes after release. For offenders between 18 and 25 who fulfill the formal requirements to serve with EM, participation in the EM-program increases the probability of completing upper secondary education by 11 % points after 1.5 years and by 18 % points 3 years after release, compared to imprisonment. The analyses show longer-term effects of electronic monitoring on educational outcomes, when given to young offenders with short-term prison sanctions who are enrolled in education at the time of conviction.

Looking at the time trend, the findings suggest that the EM-program has a short-term retention effect: keeping young offenders in the educational system, which then, in the longer run, turns into higher completion rates of upper secondary education. If the effects of the EM-program on young offenders’ educational outcomes had been limited to the first time periods, this could suggest that incarceration (directly or indirectly) forced young offenders to drop out of educational programs. The empirical analyses do not detect short-term incapacitation effects; instead, the difference between the two groups gradually increases during the 3 year follow-up period. These longer-term effects of the EM-program on the young offenders’ subsequent educational outcomes suggest that sanctioning with electronic monitoring can have rehabilitative effects, compared with imprisonment, in the longer run.

In regards to the interpretation of the results, some considerations in relation to the content of the Danish EM-program are important to discuss. The EM-program evaluated in this study consists of several elements besides house arrest under electronic surveillance, and it is not possible in the analyses to differentiate between these components. Prior qualitative research has pointed to diverted effects of the EM-program, as the fixed time schedule and the requirements to attend school help the offenders to structure their everyday lives (Jørgensen 2011). This is an example of one element in the program that is likely to enhance young offenders’ chances of finishing their educational programs. Another element is the requirement of sobriety and no drug use during the EM-program, which is controlled by unannounced visits from the DPPS. Drug testing has previously shown effects on offenders’ likelihood of school dropout post-release (Kilmer 2008). This element is a common trait of both imprisonment and the EM-program, but drug use is (similar to many other countries) common among prisoners in Danish prisons. Therefore, it is not possible to rule out that some of the treatment effect can be attributed to the alcohol and drug control in the EM-program. As mentioned above, the empirical analyses of the Danish EM-program do not distinguish between the separate program elements and how much they each contribute to the positive effects on educational outcomes. But, the empirical analyses show effects long after the end of the program (maximum duration of 92 days), which suggests that the combination of house arrest with electronic surveillance and the other elements in Danish EM-program affect the participants in the longer run. If we return to the theoretical perspective on the effects of sanctions, the empirical results do not support the deterrence perspective, which points to lower educational outcomes for offenders serving with EM, when compared to offenders serving in prison. The positive effects of the EM-program could, from the social learning and peer theory perspective, be explained by program participants having more contact with pro-social peers (family and classmates) and less interaction with criminal peers.

The study is based on a natural experiment applying IV-estimations in order to take self-selection and non-random allocation of permissions for the EM-program into account. The IV-regression models identify the average treatment effects to the treated (ATET), which means that the estimated effects apply to young offenders (18–25 years old) with short-term prison sentences, enrolled in education at the time of conviction and participating in the EM-program. The treatment effects of the EM-program can potentially be extended to a larger group of offenders, as the compliance rate in the Danish program was only 63 %, and prior studies show that around 30 % of offenders offered the chance to serve with electronic monitoring do not apply to the EM-program (Jørgensen 2011). This means that the positive effects of the EM-program on educational outcomes can potentially be furthered by increasing the application rate to the program.

In times with large prison populations and discussions regarding downsizing, it is important to recognize that alternative sanctions can have positive influences on young offenders’ future outcomes, both in terms of recidivism (Di Tella and Schargrodsky 2013; Jørgensen 2011; Marie 2015) and in regards to labor market participation (Andersen and Andersen 2014) and educational outcomes. These findings are important in order to evaluate the returns of introducing noncustodial sanctions and to inform future policy decisions and discussion on electronic monitoring. It will, however, be important to do further qualitative and quantitative research to achieve a deeper understanding of the mechanisms behind these results: how the different program elements affect offenders’ future outcomes, how sanction types influence educational trajectories and how different outcomes like crime, education and labor market participation are interrelated.

Notes

It is important to mention that empirical studies have questioned this notion of non-custodial sanctions as less harsh or severe to the individual, e.g., through examples of offenders choosing prison instead of early release with intense supervision and through offenders rating non-custodial sanctions as more severe than short-term prison sentences (Descenes et al. 1995; Payne and Gainey 1998; Petersilia and Descenes 1994; Wood and May 2003). In the Danish context, however, about 80 percent of the offenders rated electronic monitoring as less severe than prison, when asked in a questionnaire after the EM-program (Jørgensen 2011).

Previous reviews on imprisonment and reoffending document, that the empirical evidence of deterrent effects of imprisonment is non-conclusive (Mears et al. 2015; Nagin et al. 2009). This picture is also reflected in recent studies addressing selection issues and yet identifying diverse results: Bales and Piquero (2012) and Cochran et al. (2014) find higher risk of recidivism among imprisoned offenders compared to offenders e.g., on probation, whereas Kuziemko (2013) shows that the length of imprisonment lowers the risk of recidivism, and Nagin and Snodgrass (2013) find little evidence that incarceration has an impact on rearrests.

The Danish EM-program was first introduced to traffic offenders with a maximum sentence of three months in May 2005, then extended in April 2006 to all offenders between the ages of 15 and 25 with a maximum prison sentence of three months and extended in June 2008 to all offenders with a maximum prison sentence of three months (no age requirements). In 2010, the requirement of the maximum prison sentence was raised from three to five months, and finally, in July 2013, to a maximum of six months (Jørgensen 2011; Sorensen and Kyvsgaard 2009).

These numbers are based on records of young offenders between the ages of 15 and 25 offered to serve with EM within the first year after the reform. This type of information was, however, not available for this study.

In Denmark, serving in a closed prison facility with high levels of security and monitoring, where prisoners only receive permission to leave the facility on special occasions, are restricted to offenders with either a prison sentence above five years, a gang membership, a high protection need or a high risk of evasion (Damm and Gorinas 2013).

In Denmark, short-term prison sentences are widely used; 61 percent of a total of 9,967 prison sentences in 2013 were below 4 months (Department of Prison and Probation Service, 2013).

A similar identification strategy was used by Andersen and Andersen (2014) in their study of labor market outcomes, and this study contributes by analyzing educational outcomes.

In the Danish educational system, primary and lower secondary schooling levels are integrated into a compulsory nine-year program (followed by an optional 10th year). The compulsory level is followed by the upper secondary level, with the general programs lasting 2–3 years and qualifying students for higher education and the vocational programs lasting 3.5 years on average and qualifying students to enter skilled employment in the labor market.

In Denmark, the minimum age of criminal responsibility is 15 and young offenders are sentenced by the same penal code and in the same courts as adult offenders, as there is no separate juvenile justice system. A number of special sentencing and sanctioning options exist for young offenders (15–18 years old), and when placed in custody or sentenced to a prison term, they are confined in separate institutions (Kyvsgaard 2003).

Attrition in the Danish register data only occurs upon death or migration, and this entails that only two offenders are excluded because of missing educational information during the three year follow-up period. However, the case handling was prolonged and postponed the release date of 16 offenders in the treatment group. This implies that I cannot follow their educational attainments for the full 36 months. Instead of excluding these cases from the analyses (and potentially introducing selection), I have included their last educational record measured at 28–35 months. Any implications for the estimation of the treatment effect would most likely bias the EM-program coefficient downwards, as the 16 offenders in the treatment group have a shorter time period to finish the educational program.

In relation to criminal and educational history, the descriptive results could point to a small negative selection into the treatment group, as they have ‘worse’ records than the control group. If these differences between the two groups influence the results, it would most likely imply an underestimation of the effects of the EM-program.

In experimental settings, the non-compliance can be two-sided in cases with both treatment migration (when individuals in the control group are treated) and treatment dilution (when individuals in the treatment group do not receive treatment). This study of a natural experiment, with a legal reform introducing treatment at a specific date, is only subject to one-sided non-compliance due to treatment dilution.

References

Aizer A, Doyle JJ Jr (2015) Juvenile incarceration, human capital and future crime: evidence from randomly-assigned judges. Q J Econ 130(2):1–46

Akers RL (1998) Social learning and social structure: a general theory of crime and deviance. Northeastern University Press, Boston

Andersen LH, Andersen SH (2014) Effect of electronic monitoring on social welfare dependence. Criminol Public Policy 13(3):1–31

Angrist J (2001) Estimation of limited dependent variable models with dummy endogenous regressors: simple strategies for empirical practice. J Bus Econ Stat 19:12–16

Angrist J (2006) Instrumental variables methods in experimental criminological research: What, why, and how? J Exp Criminol 2:23–44

Angrist J, Pischke JS (2009) Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Apel R, Bushway S, Paternoster R, Brame R, Sweeten G (2008) Using state child labor laws to identify the causal effect of youth employment on deviant behavior and academic achievement. J Quant Criminol 24(4):337–362

Bales W, Piquero A (2012) Assessing the impact of imprisonment on recidivism. J Exp Criminol 8(1):71–101

Bayer P, Hjalmarsson R, Pozen D (2009) Building criminal capital behind bars: peer effects in juvenile corrections. Q J Econ 124(1):105–147

Becker G (1968) Crime and punishment: an economic approach. J Polit Econ 76:169–217

Bonta J, Wallace-Capretta S, Rooney J (2000) Can electronic monitoring make a difference? An evaluation of three Canadian programs. Crime Delinq 46(1):61–67

Bushway SD, Apel RJ (2010) Instrument variables in criminology and criminal justice. In: Piquero AR, Weisburd D (eds) Handbook of quantitative criminology. Springer, Berlin, pp 595–612

Card D (1999) The causal effect of education on earnings. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol Chapter 30. Elsevier, Rotterdam, pp 1802–1863

Cochran J, Mears D, Bales W (2014) Assessing the effectiveness of correctional sanctions. J Quant Criminol 30(2):317–347

Damm AP, Gorinas C (2013) Deal drugs once, deal drugs twice: peer effects in prisons on recidivism. In: Gorinas C (ed) Essays on marginalization and integration of immigrants and young criminals—a labor economics perspective. Aarhus University, Department of Economics and Business, Aarhus

Department of Prison and Probation Service (2013) The annual statistic report 2013. Department of Prison and Probation Service, Denmark

Descenes EP, Turner S, Petersilia J (1995) A dual experiment in intensive community supervision: Minnesota’s prison diversion and enhanced supervised release programs. Prison J 75:330–356

Di Tella R, Schargrodsky E (2013) Criminal recidivism after prison and electronic monitoring. J Polit Econ 121(1):28–73

Farrington D, Gallagher B, Morley L, Ledger RS, West D (1986) Unemployment, school leaving and crime. Br J Criminol 26(4):335–356

Finn MA, Muirhead-Steves S (2002) The effectiveness of electronic monitoring with violent male parolees. Justice Q 19(2):293–312

Gottfredson MR (1985) Youth employment, crime, and schooling. Dev Psychol 21(3):419–432

Hjalmarsson R (2008) Criminal justice involvement and high school completion. J Urban Econ 63:613–630

Jørgensen TT (2011) Afsoning i hjemmet. En effektevaluering af fodlænkeordningen. Justitsministeriets Forskningskontor, København

Killias M, Gilliéron G, Villard F, Poglia C (2010) How damaging is imprisonment in the long-term? A controlled experiment comparing long-term effects of community service and short custodial sentences on re-offending and social integration. J Exp Criminol 6(2):115–130

Kilmer B (2008) Does parolee drug testing influence employment and education outcomes? Evidence from a randomized experiment with noncompliance. J Quant Criminol 24(1):93–123

Kuziemko I (2013) How should inmates be released from prison? An assessment of parole versus fixed-sentence regimes. Q J Econ 128(1):371–424

Kyvsgaard B (2003) The criminal career: the Danish longitudinal study. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Lochner L, Moretti E (2004) The effect of education on crime: evidence from prison inmates, arrests, and self-reports. Am Econ Rev 94(1):155–189

Marie O (2015) Early release from prison on electronic monitoring and recidivism: a tale of two discontinuities. Unpublished manuscript

Marklund F, Holmberg S (2009) Effects of early release from prison using electronic tagging in Sweden. J Exp Criminol 5(1):41–61

Mcgloin JM (2009) Delinquency balance: revisiting peer influence. Criminology 47(2):439–477

Mears DP, Cochran JC, Cullen FT (2015) Incarceration heterogeneity and its implications for assessing the effectiveness of imprisonment on recidivism. Crim Justice Policy Rev 26(7):691–712

Nagin DS (1998) Criminal deterrence research at the outset of the twenty-first century. In: Tonry MH (ed) Crime and justice: an annual review of research, vol 23. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 1–42

Nagin DS (2013) Deterrence. In: Tonry MH (ed) Crime and justice: an annual review of research, vol 41. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 115–200

Nagin DS, Snodgrass GM (2013) The effect of incarceration on re-offending: evidence from a natural experiment in Pennsylvania. J Quant Criminol 29(4):601–642

Nagin DS, Cullen FT, Jonson CL (2009) Imprisonment and reoffending. In: Tonry MH (ed) Crime and justice: an annual review of research, vol 38. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 115–200

Nellis M, Beyens K, Kaminski D (eds) (2013) Electronically monitored punishment: international and critical perspectives. Routledge, New York

Oreopoulos P, Salvanes KG (2011) Priceless: the nonpecuniary benefits of schooling. J Econ Perspect 25(1):159–184

Payne BK (2014) It’s a small world, but I wouldn’t want to paint it: learning from Denmark’s experience with electronic monitoring. Criminol Public Policy 13(3):381–391

Payne BK, Gainey RR (1998) A qualitative assessment of the pains experienced on electronic monitoring. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 42(2):149–163

Petersilia J, Descenes EP (1994) Perceptions of punishment: inmates and staff rank the severity of prison versus intermediate sanctions. Prison J 74(3):306–328

Renzema M, Mayo-Wilson E (2005) Can electronic monitoring reduce crime for moderate to high-risk offenders? J Exp Criminol 1(2):215–237

Rumberger RW (2011) Dropping out—why students drop out of high school and what can be done about it. Harvard University Press, Harvard

Sorensen D, Kyvsgaard B (2009) Afsoning i hjemmet. En forløbsanalyse vedrørende fodlænkeordningen. Justitsministeriets Forskningskontor, København

Stevenson M (2014) Breaking bad: social influence and the path to criminality in Juvenile Jails. University of California, Berkeley, Department of Agricultural and Ressource Economics

Sweeten G (2006) Who will graduate? Disruption of high school education by arrest and court involvement. Justice Q 23(4):462–480

Villettaz P, Killias M, Zoder I (2006) The effects of custodial vs. non-custodial sentences on re-offending: a systematic review of the state of knowledge. Campbell Syst Rev 2006:13

Wood PB, May DC (2003) Racial differences in perceptions of the severity of sanctions: a comparison of prison with alternatives. Justice Q 20(32):605–631

Acknowledgments

The research was carried out in collaboration with the Rockwool Foundation Research Unit. The anonymous reviewers, Anna Piil Damm and Kim Møller are gratefully acknowledged for their valuable comments. I would like to thank Lars Højsgaard Andersen for sharing his insights about the datasets and Tanja Tambour Jørgensen and Britta Kyvsgaard for sharing their knowledge about the Danish legal system and the EM-program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Larsen, B.Ø. Educational Outcomes After Serving with Electronic Monitoring: Results from a Natural Experiment. J Quant Criminol 33, 157–178 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-016-9287-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-016-9287-8