Abstract

Objectives

The present study examines how individuals’ sanction risk perceptions are shaped by neighborhood context.

Methods

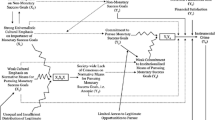

Using structural equation modeling on data from waves 6 and 7 of the National Youth Survey, we assess the direct and indirect relationships between adverse neighborhood conditions and two dimensions of sanction risk perceptions: the certainty of punishment and perceived shame. In addition, the role of shame as a mediator between neighborhood context and certainty of punishment is also investigated.

Results

The results indicate that adverse neighborhood conditions indirectly affect both forms of sanction risk perceptions, and additional results show that perceived shame fully mediates the effect of neighborhood conditions on perceptions of the certainty of punishment.

Conclusions

The perceptual deterrence/rational choice perspective will need to be revised to accommodate more explicitly the role of neighborhood context in shaping sanction risk perceptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Regarding our latter research question, we are aware that there may be a reciprocal relationship between formal sanction threats and informal sanction risk. Even so, we restrict our focus on the unidirectional pathway from perceived shame to the certainty of punishment since most of the strong arguments involving the relationship between the two dimensions of sanction risks are more focused on the effect of informal sanctions on formal sanctions (Etzioni 1988; Zimring and Hawkins 1973) and not vice versa.

The personal offending experience data collected in wave 7 with regard to the preceding year (1986) was measured as categorical variables, but the measures on offending experiences between 1984 and 1985 were measured as binary variables. For these reasons, the personal offending behavior index is constructed using binary indicators.

There was one outlying value of 12. This value has been recoded into four since it does not have any meaningful impact on the outcome.

Following the lead of Horney and Marshall (1992) and Anwar and Loughran (2011), we also employed an “arrest to crime ratio” variable. However, none of our exogenous variables successfully predicted this new ratio after it was entered in the model. Therefore, we decided to treat the two variables independently.

Maximum likelihood (ML) estimation is most commonly used in SEM. ML estimation assumes that the observed variables follow a multivariate normal distribution. As noted above, however, the categorical indicators of some of our measures in the current study do not allow us to use ML. Instead, oftentimes WLS (Weighted Least Square) has been relied upon as an alternative since it is known to be appropriate when the data do not follow a multivariate normal distribution (Bollen 1989). Nevertheless, Muthén et al. (1997) reported that WLS was found to be inferior to WLSMV and therefore WLSMV has been designated as a default estimator in Mplus when categorical endogenous variables or categorical indicators are involved (Muthen and Muthen 2010).

This correlation matrix could be obtained using the OUTPUT TECH4 option provided by M-plus. This command is useful in that it actually provides the correlation matrix derived from latent constructs rather than observed variables.

We also dropped the personal arrest experience variable, since the variable is not related to any of the dependent or the independent variables.

We recognize that, as with any study that uses a non-experimental research design, causality cannot be inferred in the present study. We have, however, established statistical associations with proper temporal ordering along with extensive controls to avoid potential spuriousness. We are therefore confident that the relationships we observed are consistent with the propositions made by the theoretical perspectives we are testing.

References

Akers RL (1998) Social learning and social structure: a general theory of crime and deviance. Northeastern University Press, Boston

Akers RL, Krohn MD, Lanza-Kaduce L, Radosevich M (1979) Social learning and deviant behavior: a specific test of a general theory. Am Sociol Rev 44:636–655

Anderson E (1999) Code of the street: decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. W. W. Norton and Company, New York

Anwar S, Loughran TA (2011) Testing a Bayesian learning theory of deterrence among serious juvenile offenders. Criminology 49:667–698

Apel R, Nagin DS (2011) General deterrence: a review of recent evidence. In: Wilson JQ, Petersilia J (eds) Crime and public policy. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 411–436

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 51:1173–1182

Beccaria C (1764) On crimes and punishment. Hackett, Indianapolis, IN

Becker GS (1968) Crime and punishment: an economic approach. J Polit Econ 76:169–217

Bernburg JG, Thorlindsson T (2007) Community structure and adolescent delinquency in Iceland: a contextual analysis. Criminology 45:415–444

Bishop DM (1984) Legal and extra legal barriers to delinquency: a panel analysis. Criminology 22:403–419

Bollen K (1989) Structural equations with latent variables. Wiley, New York

Braithwaite J (1989) Crime, shame and reintegration. Cambridge University Press, New York

Bridges GS, Stone JA (1986) Effects of criminal punishment on perceived threat of punishment: toward an understanding of specific deterrence. J Res Crime Delinq 23:207–239

Bursik RJ (1988) Social disorganization and theories of crime and delinquency: problems and prospects. Criminology 26:519–552

Bursik RJ, Grasmick HG (1993) Neighborhoods and crime: the dimensions of effective community control. Lexington Books, New York

Clarke RV, Cornish DB (2001) Rational choice. In: Paternoster R, Bachman R (eds) Explaining criminals and crime: essays in contemporary criminological theory. Roxbury, Los Angeles, pp 23–42

Cohen LE, Felson M (1979) Social change and crime rate trends: a routine activities approach. Am Sociol Rev 44:588–608

Cornish DB, Clarke RV (1986) The reasoning criminal: rational choice perspective on offending. Springer, New York

Cullen FT, Pratt TC, Miceli SL, Moon MM (2002) Dangerous liaison? Rational choice theory as the basis for correctional intervention. In: Piquero AR, Tibbetts SG (eds) Rational choice and criminal behavior: recent research and future challenges. Taylor and Francis, New York

Elliot DS, Huizinga D, Menard S (1989) Multiple problem youth: delinquency, substance use, and mental health problems. Springer, New York

Elliott DS, Wilson J, Huizinga D, Sampson R, Elliott A, Rankin B (1996) The effects of neighborhood disadvantage on adolescent development. J Res Crime Delinq 33:389–426

Etzioni A (1988) The moral dimension: toward a new economics. Free Press, New York

Fox J (1991) Regression diagnostics: an introduction, vol 79. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Gau JM, Pratt TC (2008) Broken windows or window dressing? Citizens (in)ability to tell the difference between disorder and crime. Criminol Public Policy 7:163–194

Geerken MR, Gove WR (1975) Deterrence: some theoretical considerations. Law Soc Rev 9:498–513

Gibbs JP (1975) Crime, punishment and deterrence. Elsevier, New York

Giordano PC (2010) Legacies of crime: a follow up of the children of highly delinquent girls and boys. Cambridge University Press, New York

Gorman-Smith D (2000) The interaction of neighborhood and family in delinquency. Poverty Res News 4:7–9

Gottfredson MR, Hirschi T (1990) A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA

Grasmick HG, Bursik RJ (1990) Conscience, significant others, and rational choice: extending the deterrence model. Law Soc Rev 24:837–861

Grasmick HG, Bursik RJ, Arneklev BJ (1993) Reduction in drunk driving as a response to increased threats of shame, embarrassment, and legal sanctions. Criminology 31:41–67

Harcourt BE (2001) Illusion of order: the false promise of broken windows policing. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Hay C (2001) An exploratory test of Braithwaite’s reintegrative shaming theory. J Res Crime Delinq 38:132–135

Hay C, Fortson EN, Hollist DR, Altheimer I, Schaible LM (2006) The impact of community disadvantage on the relationship between the family and juvenile crime. J Res Crime Delinq 43:326–356

Haynie DL, Silver E, Teasdale B (2006) Neighborhood characteristics, peer influence, and adolescent violence. J Quant Criminol 22(2):147–169

Horney J, Marshall IH (1992) Risk perceptions among serious offenders: the role of crime and punishment. Criminology 30:575–592

Joreskog KG, Sorobom D (1996) PRELIS 2: user’s reference guide. Scientific Software International, Chicago, IL

Kahan DM (1997) Social influence, social meaning, and deterrence. Virginia Law Rev 83:349–395

Kelling GL, Coles CM (1996) Fixing broken windows: restoring order and reducing crime in our communities. Free Press, New York

Kirk D, Papachristos AV (2011) Cultural mechanisms and the persistence of neighborhood violence. Am J Sociol 116:1190–1233

Klepper S, Nagin DS (1989) Tax compliance and perceptions of the risks of detection and criminal prosecution. Law Soc Rev 23:209–240

Kornhauser R (1978) Social sources of delinquency. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Loughran TA, Paternoster R, Piquero AR, Pogarsky G (2011) On ambiguity in perceptions of risk: implications for criminal decision making and deterrence. Criminology 49:1029–1061

Loughran TA, Piquero AR, Fagan J, Mulvey EP (2012) Differential deterrence: studying heterogeneity and changes in perceptual deterrence among serious youthful offenders. Crime Delinq 58:3–27

Makkai T, Braithwaite J (1994) The dialectics of corporate deterrence. J Res Crime Delinq 31:347–373

Meares TL, Kahan DM (1998) Law and (norms of) order in the inner city. Law Soc Rev 32:805–838

Muthen, L. K., & Muthen, B. O. (2010). M-plus 6.1: user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA

Muthén, B., du Toit, S. H. C., & Spisic, D. (1997). Robust inference using weighted least squares and quadratic estimating equations in latent variable modeling with categorical and continuous outcomes (Unpublished technical report)

Nagin DS (1998) Criminal deterrence research at the outset of the twenty-first century. In: Tonry M (ed) Crime and justice: a review of research, vol 23. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 1–42

Nagin DS, Paternoster R (1993) Enduring individual differences and rational choice theories of crime. Law Soc Rev 27:467–496

Nagin DS, Pogarsky G (2001) Integrating celerity, impulsivity, and extralegal sanction threats into a model of general deterrence: theory and evidence. Criminology 39:865–892

Nagin DS, Pogarsky G (2004) Time and punishment: delayed consequence and criminal behavior. J Quant Criminol 20:295–317

Papachristos AV (2011) Too big to fail. Criminol Public Policy 10:1053–1061

Papachristos AV, Meares TL, Fagan J (2007) Attention felons: evaluating project safe neighborhoods in Chicago. J Legal Stud 4:223–272

Papachristos AV, Wallace D, Meares TL, Fagan J (2013) Desistance and legitimacy: the impact of offender notification meetings on recidivism among high risk offenders. Available at SSRN 2240232

Paternoster R (1987) The deterrent effect of the perceived certainty and severity of punishment: a review of the evidence and issues. Justice Q 4:173–217

Paternoster R, Piquero AR (1995) Reconceptualizing deterrence: an empirical test of personal and vicarious experiences. J Res Crime Delinq 32:251–286

Paternoster R, Simpson S (1996) Sanction threats and appeals to morality: testing a rational choice model of corporate crime. Law Soc Rev 30:549–583

Patterson GR (1982) Coercive family process. Castalia, Eugene, OR

Pattillo-McCoy M (1999) Black picket fences: privilege and peril among the black middle class. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Perkins DD, Taylor RB (1996) Ecological assessments of community disorder: their relationship to fear of crime and theoretical implications. Am J Commun Psychol 24:63–108

Piliavin I, Rosemary G, Craig T, Matsueda RL (1986) Crime, deterrence, and rational choice. Am Sociol Rev 51:101–119

Piquero AR, Paternoster R (1998) An application of Stafford and Warr’s reconceptualization of deterrence to drinking and driving. J Res Crime Delinq 35:3–39

Piquero AR, Pogarsky G (2002) Beyond Stafford and Warr’s reconceptualization of deterrence: personal and vicarious experiences, impulsivity, and offending behavior. J Res Crime Delinq 39:153–186

Piquero AR, Tibbets S (1996) Specifying the direct and indirect effects of low self-control and situational factors in offenders’ decision making: toward a more complete model of rational offending. Justice Q 13:481–510

Pogarsky G, Piquero AR (2003) Can punishment encourage offending? Investigating the resetting effect. J Res Crime Delinq 40:95–120

Pogarsky G, Piquero AR, Paternoster R (2004) Modeling change in perceptions about sanction threats: the neglected linkage in deterrence theory. J Quant Criminol 20:343–369

Pogarsky G, Kim KD, Paternoster R (2005) Perceptual change in the National Youth Survey: lessons for deterrence theory and offender decision-making. Justice Q 22:1–29

Pratt TC (2009) Addicted to incarceration: corrections policy and the politics of misinformation in the United States. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Pratt TC, Cullen FT (2000) The empirical status of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory of crime: a meta-analysis. Criminology 38:931–964

Pratt TC, Cullen FT (2005) Assessing macro-level predictors and theories of crime: a meta-analysis. Crime Justice 32:373–393

Pratt TC, Turner M, Piquero AR (2004) Parental socialization and community context: a longitudinal analysis of the structural sources of self-control. J Res Crime Delinq 41:219–243

Pratt TC, Cullen FT, Blevins KR, Daigle LE, Madensen TD (2006) The empirical status of deterrence theory: a meta-analysis. In: Cullen FT, Wright JP, Blevins KR (eds) Taking stock: the status of criminological theory (advances in criminological theory, vol 15. Transaction Publishing, New Brunswick, NJ, pp 367–395

Pratt TC, Cullen FT, Sellers CS, Winfree T Jr, Madensen TD, Daigle LE, Fearn NE, Gau JM (2010) The empirical status of social learning theory: a meta-analysis. Justice Q 27:765–802

Reisig MD, Pratt TC (2011) Low self-control and imprudent behavior revisited. Deviant Behav 32:589–625

Reisig MD, Wolfe S, Holtfreter K (2011) Legal cynicism, legitimacy, and criminal offending: the nonconfounding effect of low self-control. Crim Justice Behav 38:1265–1279

Sampson RJ (2012) Great American city: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL

Sampson RJ, Bartusch DJ (1998) Legal cynicism and (subcultural?) Tolerance of deviance: the neighborhood context of racial differences. Law Soc Rev 32:777–804

Sampson RJ, Laub JH (1993) Crime in the making: pathways and turning points through life. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW (1999) Systematic social observation of public spaces: a new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. Am J Sociol 105:603–651

Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley T (2002) Assessing neighborhood effects: social processes and new directions in research. Annu Rev Sociol 28:443–478

Shaw CR, McKay HD (1942) Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Simons RL, Johnson C, Beaman J, Conger R, Whitbeck L (1996) Parents and peer group as mediators of the effect of neighborhood structure on adolescent problem behavior. Am J Neighborhood Psychol 24:145–171

Simons RL, Simons LG, Burt CH, Brody GH, Cutrona C (2005) Collective efficacy, authoritative parenting and delinquency: a longitudinal test of a model integrating community- and family-level processes. Criminology 43:989–1029

Skogan WG (1990) Disorder and decline: crime and the spiral of decay in American neighborhoods. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

St. Jean PKB (2007) Pockets of crime: broken windows, collective efficacy, and the criminal point of view. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Stafford MC, Warr M (1993) A reconceptualization of general and specific deterrence. J Res Crime Delinq 30:123–135

Taylor RB (1997) Social order and disorder of street blocks and neighborhoods: ecology, microecology, and the systemic model of social disorganization. J Res Crime Delinq 34:113–155

Tittle CR (1980) Sanctions and social deviance: the question of deterrence. Praeger, New York

Tittle CR, Botchkovar EV (2005) Self-control, criminal motivation and deterrence: an investigation using Russian respondents. Criminology 43:307–353

Turanovic, J. J., & Pratt, T. C. (2013). The consequences of maladaptive coping: integrating general strain and self-control theories to specify a causal pathway between victimization and offending. J Quant Criminol. doi:10.1007/s10940-012-9180-z

Turner MG, Hartman JL, Bishop DM (2007) The effects of prenatal problems, family functioning, and neighborhood disadvantage in predicting life-course-persistent offending. Crim Justice Behav 34:1241–1261

Tyler T (1990) Why people obey the law. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

Williams KR, Hawkins R (1986) Perceptual research on general deterrence: a Critical overview. Law Soc Rev 20:545–572

Wilson JQ, Kelling GL (1982) Broken windows: the police and neighborhood safety. Atl Mon 127:29–38

Zimring FE, Hawkins GJ (1973) Deterrence: the legal threat in crime control. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, B., Pratt, T.C. & Wallace, D. Adverse Neighborhood Conditions and Sanction Risk Perceptions: Using SEM to Examine Direct and Indirect Effects. J Quant Criminol 30, 505–526 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-013-9212-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-013-9212-3