Abstract

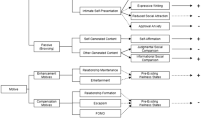

This research expands past investigations into the influence of low self-control as a risk factor for criminal victimization. Specifically, we consider two questions: (1) whether low self-control at one point in time can predict future victimization, and (2) whether victims alter lifestyle choices (like their own delinquency and contact with delinquent peers) in response to their earlier victimization. We answered these questions using three waves of adolescent panel data from the evaluation of the Gang Resistance Education and Training program. Our results support the predictions of self-control theory, showing that low self-control measured at an earlier time is associated with later victimization, even after controlling for past victimization, delinquency, social bonds, and delinquent peer contact. Likewise, self-control appears to influence the relationship between earlier victimization and later lifestyles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

There is some evidence suggesting that, at least for homeless and runaway youth, that drinking activity is associated with less victimization rather than more. Baron et al. (2001) speculated that this was because street people tend to be more judicious in locating a relatively inaccessible place to pass out after drinking.

We used the multiple imputations by chained equations “ICE” available in Stata 9 to impute missing values (Royston 2005a, b). This involved a three-step procedure in which we used the ICE function to generate 10 imputed data sets. We then estimated regression models separately for each of the 10 imputed data sets. Finally, we computed the pooled parameter estimates of the 10 regressions to account for the possible underestimation of standard errors that may be observed in single imputation procedures to obtain more precise parameter estimates (Acock 2005; Rubin 1987; Schafer 1997). Furthermore, to assess if our results were influenced by the number of data sets imputed, we estimated as many as 20 data sets with no improvement in precision above what 10 data sets generated (also see von Hippel 2005).

We capped the upper bound to three victimization incidents because very few adolescents reported more than three victimizations.

The GREAT data contained eight items adapted from the Grasmick et al. (1993) scale. In the current study, we used these eight items to form our low self-control construct.

During our initial data analysis runs, we incorporated items measuring such themes as “exposure to gangs at school” and “unattended lifestyles.” Net of the other variables included in the analysis, their influence on victimization was negligible. We declined to include these measures in the results presented here because having an excessively large number of items in a latent variable structural equation model, relative to the sample size, would have resulted in insufficient degrees of freedom, thus preventing the model from converging.

Only one of the control variables (sex) emerged significant. Boys were more likely to be victimized than girls. However, the pattern of results for boys and girls were virtually the same.

To assess whether our results were victimization specific, we disaggregated victimization into the three specific types used in our analyses. The results did not change and maintained the pattern presented in the models.

In every case, the means for the low self-control group were significantly higher than the means for the high self-control group. For example, the low self-control group reported higher levels of victimization, associations with delinquent peers, and delinquency. All t-values were significant at 0.01.

These path coefficients are significantly different. We used the equality of coefficients test which allows us to directly compare coefficient differences across models using the following equation: \(t=b_1-b_2 /\sqrt {(\hbox{SE}\,b_1)^{2}+(\hbox{SE}\,b_2)^2} \) (Paternoster et al. 1998). While victimization is stable across both high and low self-control groups, a closer look at the coefficients revealed that victimization risk has a stronger positive effect for the low self-control group (0.56 vs. 0.38; t = 2.76; P < 0.05). We also followed the same procedures for victimization to delinquent peer associations. Again the effect of victimization to delinquent peers is stronger for the low self-control group (0.38 vs. 0.22; t = 2.41; P < 0.05). It should be noted that we used unstandardized parameters for model comparisons.

Other research appears to support this conclusion that experience with “negative” earlier events apparently does not lead to changes in behavior. Piquero and Pogarsky (2002), for instance, found that the receipt of punishment had a positive relationship with later offending behavior. Moreover, the perceptions of the offenders about their risk of punishment appeared unaffected by their earlier misfortune.

We also believe that evidence that criminological themes like the stability of crime apply to victimization makes a still stronger case for extending other theories of crime to victimization. We are indebted to an anonymous referee for pointing out the possibility that Agnew’s (1992) general strain theory and social learning theory (Akers 1985) may have relevance. For example, it is plausible that persons cope with victimization by lashing out, which further increases the chances for re-victimization. Individuals may also become withdrawn and depressed (i.e., retreat) in response to victimization, thereby marginalizing themselves and increasing their vulnerability (see, also, Felson 1992). Individuals may also, as a consequence of certain types of victimization, develop behavior patterns that endorse the use of crime/violence in interpersonal interaction, which again increase future victimization risk. Although the victimization literature on these theories is virtually nonexistent, it is our view that knowledge about victimization could only benefit from testing ideas originally intended for explaining crime, leading to more complex and informative analyses than those offered to date.

We found support for our hypothesized models. However, one anonymous referee pointed out that the effect sizes for our theoretical variables range from medium ( < 0.30) to small ( < 0.10) using Cohen’s (1988) recommendations (also see Kline, 2005). Thus, our conclusions should be interpreted with these effect sizes in mind.

References

Acock A (2005) Working with missing values. J Marriage Fam 67:1012–1028

Agnew R (1992) Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology 30:47–87

Akers RL (1985) Deviant behavior: a social learning approach. Wadsworth, Belmont, CA

Arbuckle JL, Wothke W (1999) AMOS 4.0 user’s guide. SPSS, Chicago

Baron SW, Kennedy LW, and Forde DR (2001) Male street youths’ conflict: The role of background, subcultural, and situational factors. Justice Quart 18:759–789

Bollen K (1989) Structural equations with latent variables. John Wiley and Sons, New York

Cairns RB, Cairns BD (1994) Lifelines and risks: pathways of youth in our time. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Academic Press, New York

Cohen LE, Felson M (1979) Social change and crime rate trends: a routine activity approach. Am Sociol Rev 44:588–608

Cook PJ (1986) The demand and supply of criminal opportunities. In: Tonry M, Morris N (eds) Crime and justice: an annual review of research. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 1–27

Dugan L (1999) The effect of criminal victimization on a household’s moving decision. Criminology 37:903–930

Esbensen F (2003) Evaluation of the Gang Resistance Education and Training (GREAT Program in the United States, 1995–1999. Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, Ann Arbor, MI

Esbensen F, Osgood DW (1999) Gang resistance educations and training (GREAT): results from the national evaluation. J Res Crime Delinq 36:194–225

Evans TD, Cullen FT, Burton Jr VS, Dunaway RG, Benson ML (1997) Social consequences of self-control: testing the general theory of crime. Criminology 35:475–504

Felson RB (1992) Kick ‘em when they’re down: explanations of the relationship between stress and interpersonal aggression and violence. Sociol Quart 33:1–16

Felson M (1998) Crime and everyday life. Pine Forge, Thousand Oaks, CA

Finkelhor D, Dziuba-Leatherman J (1995) Victimization prevention programs: a national survey of children’s exposure and reactions. Child Abuse Negl 19:129–139

Fisher BS, Sloan JJ, Cullen FT, Lu C (1998) Crime in the ivory tower: the level and sources of student victimization. Criminology 36:671–710

Forde DR, Kennedy LW (1997) Risky lifestyles, routine activities, and the general theory of crime. Justice Quart 14:265–294

Garofalo J (1981) The fear of crime: causes and consequences. J Crim Law Criminol 72:839–857

Garofalo J (1987) Reassessing the lifestyle model of criminal victimization. In: Gottfredson MR, Hirschi T (eds), Positive criminology. Sage, Newbury Park, CA

Gottfredson M, Hirschi T (1987) The methodological adequacy of longitudinal research on crime. Criminology 25:581–614

Gottfredson MR, Hirschi T (1990) A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA

Gover AR (2004) Risky lifestyles and dating violence: a theoretical test of violent victimization. J Crim Justice 32:171–180

Grasmick HG, Tittle CR, Bursik RJ, Arneklev BJ (1993) Testing the core empirical implications of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory of crime. J Res Crime Delinq 30:5–29

Haynie DL (2001) Delinquent peers revisited: does network structure matter?. Am J Sociol 106:1013–1057

Hechter M, Kanazawa S (1997) Sociological rational choice theory. Ann Rev Sociol 23:191–214

Hindelang MJ, Gottfredson MR, Garofalo J (1978) Victims of personal crime: an empirical foundation for a theory of personal victimization. Ballinger, Cambridge, MA

Hirschi T (1969) Causes of delinquency. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

Hirschi T, Gottfredson MR (1983) Age and the explanation of crime. Am J Sociol 89:552–584

Hoelter J (1983) The analysis of covariance structures: goodness of fit indices. Sociol Methods Res 11:325–344

Jensen GF, Brownfield D (1986) Gender, lifestyles, and victimization: beyond routine activity theory. Viol Victims 1:85–99

Junger M, West R, Timman R (2001) Crime and risky behavior in traffic: an example of cross-situational consistency. J Res Crime Delinq 38:439–359

Jussim L, Osgood DW (1989) Influence and similarity among friends: an integrated model applied to incarcerated adolescents. Soc Psychol Quart 84:98–112

Karmen AJ (2003) Crime victims. Wadsworth, Belmont, CA

Keane C (1998) Evaluating the influence of fear of crime as an environmental mobility restrictor on women’s routine activities. Env Behav 30:60–74

Kline RB (2005) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press, New York

Lauritsen JL (2001) The social ecology of violent victimization: Individual and contextual effects in the NCVS. J Quant Criminol 17:3–32

Lauritsen JL, Laub JH, Sampson RJ (1992) Conventional and delinquent activities: implications for the prevention of violent victimization among adolescents. Viol Victims 7:91–108

Lauritsen JL, Sampson RJ, Laub JH (1991) Addressing the link between offending and victimization among adolescents. Criminology 29:265–291

Miethe TD, Meier RF (1994) Crime and its social context: Toward an integrated theory of offenders, victims, and situations. State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

Miethe TD, Stafford MC, Long JS (1987) Social differentiation in criminal victimization: a test of routine activities/lifestyles theories. Am Sociol Rev 52:184–194

Mustaine EE, Tewksbury R (1998) Predicting risks of larceny theft victimization: a routine activity analysis using refined activity measures. Criminology 36:829–858

Osborn DR, Tseloni A (1998) The distribution of household property crimes. J Quant Criminol 14:307–330

Osgood DW, Wilson JK, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD (1996) Routine activities and individual deviant behavior. Am Sociol. Rev 61:635–655

Paternoster R, Brame R, Mazerolle P, Piquero A (1998) Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology 36:859–866

Pease K, Laylock G (1996) Revictimization: reducing the heat on hot victims. research in action. National Institute of Justice, Washington, DC

Piquero AR, Gomez-Smith Z, Langton L (2004) Discerning unfairness where others may not: low self-control and unfair sanction perceptions. Criminology 42:699–733

Piquero AR, Hickman MJ (2003) Extending Tittle’s control balance theory to account for victimization. Crim Justice Behav 30:282–301

Piquero AR, Pogarsky G (2002) Beyond Stafford and Warr’s reconceptualization of deterrence: personal and vicarious experiences, impulsivity, and offending behavior. J Res Crime Delinq 39:153–186

Piquero AR, MacDonald J, Dobrin A, Daigle L, Cullen FT (2005) Studying the relationship between violent death and violent re-arrest. J Quant Criminol 21:55–71

Pratt TC, Cullen FT (2000) Empirical status of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory of crime: a meta-analysis. Criminology 38:931–964

Rountree PW, Land KC (1996) Burglary victimization, perceptions of crime risk, and routine activities: a multilevel analysis across Seattle neighborhoods and census tracts. J Res Crime Delinq 33:147–180

Rountree PW, Land KC, Miethe TD (1994) Macro-micro integration in the study of victimization: a hierarchical logistic model analysis across Seattle neighborhoods. Criminology 32:387–414

Royston P (2005a) Multiple imputation of missing values: update. Stata J 5:188–201

Royston P (2005b) Multiple imputation of missing values: update of ice. Stata J 5:527–536

Rubin DB (1987) Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Wiley, New York

Sampson RJ, Lauritsen JL (1990) Deviant lifestyles, proximity to crime, and the offender-victim link. J Res Crime Delinq 27:110–139

Schafer JL (1997) Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. Chapman & Hall, London

Schreck CJ (1999) Victimization and low self-control: an extension and test of a general theory of crime. Justice Quart 16:633–654

Schreck CJ, Fisher BS (2004) Specifying the influence of family and peers on violent victimization: Extending routine activities and lifestyles theories. J Interpersonal Viol 19:1021–1041

Schreck CJ, Fisher BS, Miller JM (2004) The social context of violent victimization: a study of the delinquent peer effect. Justice Quart 21:23–48

Schreck CJ, Miller JM, Gibson C (2003) Trouble in the school yard: a study of the risk factors of victimization at school. Crime Delinq 49:460–484

Schreck CJ, Wright RA, Miller JM (2002) A study of the individual and situational antecedents of violent victimization. Justice Quart 19:159–180

Sherif M, Sherif CW (1964) Reference groups: exploration into conformity and deviation of adolescents. Harper & Row, New York

Skogan WG, Maxfield MG (1981) Coping with crime: individual and neighborhood reactions. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA

Singer SI (1981) Homogeneous victim-offender populations: a review and some research implications. J Crim Law Criminol 72:779–788

Stewart EA, Elifson KW, Sterk CE (2004) Integrating the general theory into an explanation of violent victimization among female offenders. Justice Quart 21:159–182

Tedeschi J, Felson RB (1994) Violence, aggression, and coercive action. American Psychological Association Books, Washington, DC

von Hippel PT (2005) How many imputations are needed? A comment of Hershberger and Fisher (2003). Struct Equation Model 12:334–335

Warr M (1994) Public perceptions and reactions to violent offending and victimization. In: Reiss AJ, Roth JA (eds) Understanding and preventing violence: consequences and control. National Academy Press, Washington, DC

Warr M (1996) Organization and instigation in delinquent groups. Criminology 31:17–40

Warr M, Stafford M (1983) Fear of victimization: a look at the proximate causes. Soc Forces 61:1033–1043

Wilcox P, Land KC, Hunt SA (2003) Criminal circumstance: a dynamic, multicontextual criminal opportunity theory. Aldine de Gruyter, New York

Wittebrood K, Nieuwbeerta P (2000) Criminal victimization during one’s life course: the effects of previous victimization and patterns of routine activities. J Res Crime Delinq 37:91–122

Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM (2000) Childhood and adolescent predictors of physical assault: a prospective longitudinal study. Criminology 38:233–261

Acknowledgments

The data for this study were originally collected by Finn Esbensen and made available through the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research. Neither Esbensen nor ICPSR bear any responsibility for the analyses and results presented here. The authors gratefully acknowledge Alex Piquero, Donna Bishop, Pamela Wilcox, and the anonymous referees for their constructive comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schreck, C.J., Stewart, E.A. & Fisher, B.S. Self-control, Victimization, and their Influence on Risky Lifestyles: A Longitudinal Analysis Using Panel Data. J Quant Criminol 22, 319–340 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-006-9014-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-006-9014-y