Abstract

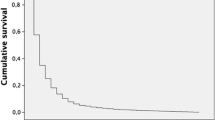

Objective To compare the duration of financial compensation and the occurrence of a second episode of compensation of workers with occupational back pain who first sought three types of healthcare providers. Methods We analyzed data from a cohort of 5511 workers who received compensation from the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board for back pain in 2005. Multivariable Cox models controlling for relevant covariables were performed to compare the duration of financial compensation for the patients of each of the three types of first healthcare providers. Logistic regression was used to compare the occurrence of a second episode of compensation over the 2-year follow-up period. Results Compared with the workers who first saw a physician (reference), those who first saw a chiropractor experienced shorter first episodes of 100 % wage compensation (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] = 1.20 [1.10–1.31], P value < 0.001), and the workers who first saw a physiotherapist experienced a longer episode of 100 % compensation (adjusted HR = 0.84 [0.71–0.98], P value = 0.028) during the first 149 days of compensation. The odds of having a second episode of financial compensation were higher among the workers who first consulted a physiotherapist (OR = 1.49 [1.02–2.19], P value = 0.040) rather than a physician (reference). Conclusion The type of healthcare provider first visited for back pain is a determinant of the duration of financial compensation during the first 5 months. Chiropractic patients experience the shortest duration of compensation, and physiotherapy patients experience the longest. These differences raise concerns regarding the use of physiotherapists as gatekeepers for the worker’s compensation system. Further investigation is required to understand the between-provider differences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- ALBI:

-

Acute low back pain injury program of care

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DC:

-

Doctor of chiropractic

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- IRSST:

-

Institut de Recherche en Santé Sécurité au Travail

- IWH:

-

Institute for Work and Health

- MD:

-

Medical doctor

- NOC:

-

National occupational code

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PT:

-

Physiotherapist

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristics

- R-RTW:

-

Readiness to return to work

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SIC-80:

-

Standard international classification 1980

- WSIB:

-

Workplace Safety and Insurance Board

References

Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, Blyth F, Woolf A, Bain C, et al. The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):968–74. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204428.

Schmidt CO, Raspe H, Pfingsten M, Hasenbring M, Basler HD, Eich W, et al. Back pain in the German adult population: prevalence, severity, and sociodemographic correlates in a multiregional survey. Spine. 2007;32(18):2005–11. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e318133fad8 (Phila Pa 1976).

Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Côté P. The Saskatchewan health and back pain survey: the prevalence of low back pain and related disability in Saskatchewan adults. Spine. 1998;23(17):1860–6.

Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Martin BI. Back pain prevalence and visit rates: estimates from U.S. national surveys, 2002. Spine. 2006;31(23):2724–7. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000244618.06877.cd (Phila Pa 1976).

Leroux I, Dionne CE, Bourbonnais R, Brisson C. Prevalence of musculoskeletal pain and associated factors in the Quebec working population. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2005;78(5):379–86. doi:10.1007/s00420-004-0578-2.

WSIB. By the numbers: 2013 WSIB statistical report. Toronto, ON: Workplace Safety and Insurance Board. http://www.wsibstatistics.ca. Accessed 3 Aug 2014.

Lamarche D, Veilleux F, Provencher J, Boucher P. Statistiques sur les affections vertébrales 2005–2008. Québec; QC: Commission de la santé et de la sécurité du travail du Québec2009 Contract No.: ISBN: 978-2-550-56793-6.

Loi sur les accidents du travail et les maladies professionnelles (LATMP). L.R.Q., c. A-3.001 (1985).

WSIB. Un plus grand choix de professionels de la santé pour les travailleurs blessés ou malades. Bull Polit. 2004;17(1):3.

McIntosh G, Frank J, Hogg-Johnson S, Bombardier C, Hall H. Prognostic factors for time receiving workers’ compensation benefits in a cohort of patients with low back pain. Spine. 2000;25(2):147–57 (Phila Pa 1976).

Ojha HA, Snyder RS, Davenport TE. Direct access compared with referred physical therapy episodes of care: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2014;94(1):14–30. doi:10.2522/ptj.20130096.

Gregory AW, Pentland W. Program of care for acute low back injuries: one-year evaluation report. Maitland Consulting Inc.; 2004.

Sears JM, Wickizer TM, Franklin GM, Cheadle AD, Berkowitz B. Nurse practitioners as attending providers for injured workers: evaluating the effect of role expansion on disability and costs. Med Care. 2007;45(12):1154–61. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181468e8c.

Turner JA, Franklin G, Fulton-Kehoe D, Sheppard L, Stover B, Wu R, et al. ISSLS prize winner: early predictors of chronic work disability: a prospective, population-based study of workers with back injuries. Spine. 2008;33(25):2809–18. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817df7a7 (Phila Pa 1976).

Steenstra IA, Busse JW, Tolusso D, Davilmar A, Lee H, Furlan AD, et al. Predicting time on prolonged benefits for injured workers with acute back pain. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25(2):267–78. doi:10.1007/s10926-014-9534-5.

Steenstra IA, Franche RL, Furlan AD, Amick B 3rd, Hogg-Johnson S. The added value of collecting information on pain experience when predicting time on benefits for injured workers with back pain. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;. doi:10.1007/s10926-015-9592-3.

Bultmann U, Franche RL, Hogg-Johnson S, Cote P, Lee H, Severin C, et al. Health status, work limitations, and return-to-work trajectories in injured workers with musculoskeletal disorders. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(7):1167–78. doi:10.1007/s11136-007-9229-x.

Blanchette M-A. Première ligne de soins pour les travailleurs atteints de rachialgie occupationnelle: étude du délai de consultation et du premier fournisseur de services de santé [Ph.D. thesis by articles]: Université de Montréal. 2016.

Wilkins R. PCCF+ version 4G user’s guide: automated geographic coding based on the statistics Canada postal code conversion files. Health Analysis and Measurement Group. Statistics Canada, 64 pp. 2006.

Statistics Canada. Standard industrial classification—establishments (SIC-E) 1980. Statistics Canada. 2014. http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3VD.pl?Function=getVD&TVD=53446. Accessed 12 Aug 2015.

WSIB. Operational policy: responsibilities of the workplace parties in work reintegration. 2011.

Hébert F, Duguay P, Massicotte P, Levy M. Révision des catégories professionnelles utilisées dans les études de l’IRSST portant sur les indicateurs quinquennaux de lésions professionnelles. Montréal: IRSST1996 Contract No.: Études et recherches/Guide technique R-137.

Duguay P, Boucher A, Busque M, Prud’homme P, Vergara D. Lésions professionnelles indemnisées au Québec en 2005–2007: profil statistique par industrie-catégorie professionnelle. Études et recherches/Rapport R-749 Montréal: IRSST. 2012;202.

Dasinger LK, Krause N, Deegan LJ, Brand RJ, Rudolph L. Physical workplace factors and return to work after compensated low back injury: a disability phase-specific analysis. J Occup Environ Med. 2000;42(3):323–33.

Sinnott P. Administrative delays and chronic disability in patients with acute occupational low back injury. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(6):690–9. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181a033b5.

Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Wiley; 2004.

Vittinghoff E, Glidden DV, Shiboski SC, McCulloch CE. Predictor selection. Regression methods in biostatistics. Berlin: Springer; 2012. p. 395–429.

Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Battie M, Street J, Barlow W. A comparison of physical therapy, chiropractic manipulation, and provision of an educational booklet for the treatment of patients with low back pain. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(15):1021–9. doi:10.1056/nejm199810083391502.

Hurwitz EL, Morgenstern H, Harber P, Kominski GF, Belin TR, Yu F, et al. A randomized trial of medical care with and without physical therapy and chiropractic care with and without physical modalities for patients with low back pain: 6-month follow-up outcomes from the UCLA low back pain study. Spine. 2002;27(20):2193–204. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000029253.40547.84 (Phila Pa 1976).

Hurwitz EL, Morgenstern H, Kominski GF, Yu F, Chiang LM. A randomized trial of chiropractic and medical care for patients with low back pain: eighteen-month follow-up outcomes from the UCLA low back pain study. Spine. 2006;31(6):611–21. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000202559.41193.b2 (Phila Pa 1976; discussion 22).

Meade TW, Dyer S, Browne W, Frank AO. Randomised comparison of chiropractic and hospital outpatient management for low back pain: results from extended follow up. BMJ. 1995;311(7001):349–51.

Meade TW, Dyer S, Browne W, Townsend J, Frank AO. Low back pain of mechanical origin: randomised comparison of chiropractic and hospital outpatient treatment. BMJ. 1990;300(6737):1431–7.

Petersen T, Larsen K, Nordsteen J, Olsen S, Fournier G, Jacobsen S. The McKenzie method compared with manipulation when used adjunctive to information and advice in low back pain patients presenting with centralization or peripheralization: a randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2011;36(24):1999–2010. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e318201ee8e (Phila Pa 1976).

Skargren EI, Carlsson PG, Oberg BE. One-year follow-up comparison of the cost and effectiveness of chiropractic and physiotherapy as primary management for back pain. Subgroup analysis, recurrence, and additional health care utilization. Spine. 1998;23(17):1875–83 (Phila Pa 1976; discussion 84).

Skargren EI, Oberg BE, Carlsson PG, Gade M. Cost and effectiveness analysis of chiropractic and physiotherapy treatment for low back and neck pain. Six-month follow-up. Spine. 1997;22(18):2167–77 (Phila Pa 1976).

Baldwin ML, Cote P, Frank JW, Johnson WG. Cost-effectiveness studies of medical and chiropractic care for occupational low back pain. A critical review of the literature. Spine J. 2001;1(2):138–47. doi:10.1016/S1529-9430(01)00016-X.

Brown A, Angus D, Chen S, Tang Z, Milne S, Pfaff J et al. Costs and outcomes of chiropractic treatment for low back pain (structured abstract). Health Technology Assessment Database 2005.

Butler RJ, Johnson WG. Adjusting rehabilitation costs and benefits for health capital: the case of low back occupational injuries. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20(1):90–103. doi:10.1007/s10926-009-9206-z.

Cote P, Cassidy JD, Carroll L. The treatment of neck and low back pain: who seeks care? who goes where? Med Care. 2001;39(9):956–67.

Wasiak R, Pransky GS, Atlas SJ. Who’s in charge? Challenges in evaluating quality of primary care treatment for low back pain. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14(6):961–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00890.x.

Hurwitz EL, Chiang LM. A comparative analysis of chiropractic and general practitioner patients in North America: findings from the joint Canada/United States Survey of Health, 2002–03. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:49. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-6-49.

Cote P, Baldwin ML, Johnson WG. Early patterns of care for occupational back pain. Spine. 2005;30(5):581–7. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000154613.17511.dd (Phila Pa 1976).

Richardson B, Shepstone L, Poland F, Mugford M, Finlayson B, Clemence N. Randomised controlled trial and cost consequences study comparing initial physiotherapy assessment and management with routine practice for selected patients in an accident and emergency department of an acute hospital. Emerg Med J EMJ. 2005;22(2):87–92. doi:10.1136/emj.2003.012294.

Fritz JM, Kim J, Dorius J. Importance of the type of provider seen to begin health care for a new episode low back pain: associations with future utilization and costs. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015. doi:10.1111/jep.12464.

Allen H, Wright M, Craig T, Mardekian J, Cheung R, Sanchez R, et al. Tracking low back problems in a major self-insured workforce: toward improvement in the patient’s journey. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(6):604–20. doi:10.1097/jom.0000000000000210.

Amorin-Woods LG, Beck RW, Parkin-Smith GF, Lougheed J, Bremner AP. Adherence to clinical practice guidelines among three primary contact professions: a best evidence synthesis of the literature for the management of acute and subacute low back pain. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2014;58(3):220–37.

Lim KL, Jacobs P, Klarenbach S. A population-based analysis of healthcare utilization of persons with back disorders: results from the Canadian Community Health Survey 2000–2001. Spine. 2006;31(2):212–8 (Phila Pa 1976).

Plenet A, Gourmelen J, Chastang JF, Ozguler A, Lanoe JL, Leclerc A. Seeking care for lower back pain in the French population aged from 30 to 69: the results of the 2002–2003 Decennale Sante survey. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2010;53(4):224–31. doi:10.1016/j.rehab.2010.03.006 (31–8).

Nyiendo J, Haas M, Goldberg B, Sexton G. Patient characteristics and physicians’ practice activities for patients with chronic low back pain: a practice-based study of primary care and chiropractic physicians. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24(2):92–100. doi:10.1067/mmt.2001.112565.

Sharma R, Haas M, Stano M. Patient attitudes, insurance, and other determinants of self-referral to medical and chiropractic physicians. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(12):2111–7.

Cote P, Hogg-Johnson S, Cassidy JD, Carroll L, Frank JW, Bombardier C. Initial patterns of clinical care and recovery from whiplash injuries: a population-based cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(19):2257–63. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.19.2257.

Hurwitz EL, Morgenstern H. The effects of comorbidity and other factors on medical versus chiropractic care for back problems. Spine. 1997;22(19):2254–63 (Phila Pa 1976; discussion 63–4).

Hestbaek L, Munck A, Hartvigsen L, Jarbol DE, Sondergaard J, Kongsted A. Low back pain in primary care: a description of 1250 patients with low back pain in danish general and chiropractic practice. Int J Fam Med. 2014;2014:106102. doi:10.1155/2014/106102.

Kosny A, Maceachen E, Ferrier S, Chambers L. The role of health care providers in long term and complicated workers’ compensation claims. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21(4):582–90. doi:10.1007/s10926-011-9307-3.

Cote P, Hogg-Johnson S, Cassidy JD, Carroll L, Frank JW, Bombardier C. Early aggressive care and delayed recovery from whiplash: isolated finding or reproducible result? Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(5):861–8. doi:10.1002/art.22775.

Cote P, Soklaridis S. Does early management of whiplash-associated disorders assist or impede recovery? Spine. 2011;36(25 Suppl):S275–9. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182388d32 (Phila Pa 1976).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ashleigh Burnet and many others from the WSIB for facilitating access to data. M. A. Blanchette is currently supported by a Ph.D. fellowship from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) and previously received Ph.D. Grants from both the Quebec Chiropractic Foundation and the CIHR strategic training program in transdisciplinary research on public health intervention (4P). The data extraction was funded through a grant from the WSIB Research Advisory Committee. Dr. Hogg-Johnson reports grants from Workplace Safety & Insurance Board Research Advisory Council, during the conduct of the study; grants from Ontario Ministry of Labour, outside the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no other conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Blanchette, MA., Rivard, M., Dionne, C.E. et al. Association Between the Type of First Healthcare Provider and the Duration of Financial Compensation for Occupational Back Pain. J Occup Rehabil 27, 382–392 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-016-9667-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-016-9667-9