Abstract

Interactional synchrony refers to the coordination of movements between individuals in both timing and form during interpersonal communication. Most previous studies in Western culture used a coding methodology and concluded that interactional synchrony occurred for positive episodes but not for negative episodes (e.g., Charny, E. J. (1966). Psychosomatic Medicine, 28, 305–315). In this study, we examined interactional synchrony using a between-participants pseudosynchrony experimental paradigm (Bernieri, F. J., & Rosenthal, R. (1991). In R. S. Feldman & B. Rime (Eds.), Fundamentals of nonverbal behavior (pp. 401–432). New York: Cambridge University Press). Sixty Japanese female university students viewed interaction clips and judged the level of perceived synchrony. The results show that interactional synchrony was perceived in negative episodes as well as in positive episodes. The degree of perceived synchrony was higher in positive episodes than in negative episodes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For the terms used in discussing the pseudosynchrony experimental paradigm, we followed the example of Bernieri and Rosenthal (1991), which systematically reviewed the studies of interactional synchrony.

There may be some differences between men and women in nonverbal behavior perception (Hall, 1984). Although we only report the results for female participants, we also analyzed the results for male participants. Our results were limited by the much smaller male sample size. However, we did not find significant difference between male and female participants on scores of perceived synchrony.

The rating items used in the pilot study were the same as in the following experiment. We describe some details about the rating items in the following procedure.

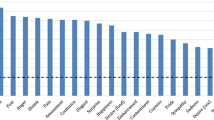

We made comparisons of the mean ratings for the three aspects of perceived synchrony between the positive and negative episodes conditions. The results showed the same tendency. The mean ratings of simultaneous movement (t(59) = 6.70, p < .001), tempo similarity(t(59) = 6.72, p < .001), and coordination and smoothness (t(59) = 6.60, p < .001), were significantly higher for the positive episodes condition than for the negative episodes condition.

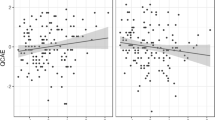

There was not a significant difference between internal pseudo-interaction and external pseudo-interaction.

In this study, we first conducted a one-way ANOVA with one factor of three levels (genuine, internal pseudo-interactions, and external pseudo-interactions) for each emotional condition to test Hypothesis 1. Next, to compare perceived synchrony in the conversations about positive episodes with that in the conversations about negative episodes, we conducted a 3 × 2 ANOVA. We considered the one-way ANOVA as desirable for the test of Hypothesis 1, because the pseudosynchrony experimental paradigm was a method in which stimuli were compared to each other to illustrate the occurrence of interactional synchrony. After that, we conducted a 3 × 2 ANOVA as an additional analysis to compare perceived synchrony in the conversations about positive episodes with the conversations about negative episodes to reveal more details about the effect of the emotional tone of the conversation.

References

Argyle, M., & Dean, J. (1965). Eye contact, distance and affiliation. Sociometry, 28, 287–304.

Baron, R. M., & Boudreau, L. A. (1987). An ecological perspective on integrating personality and social psychology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 1222–1228.

Bernieri, F. J. (1988). Coordinated movement and rapport in teacher–student interactions. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 12, 120–138.

Bernieri, F. J., Davis, J. M., Rosenthal, R., & Knee, C. R. (1994). Interactional synchrony and rapport: Measuring synchrony in displays devoid of sound and facial affect. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 303–311.

Bernieri, F. J., & Gillis, J. S. (1995). The judgment of rapport: A cross-cultural comparison between Americans and Greeks. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 19, 115–130.

Bernieri, F. J., Gillis, J. S., Davis, J. M., & Grahe, J. E. (1996). Dyad rapport and the accuracy of its judgment across situations: A lens model analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 110–129.

Bernieri, F. J., Reznick, J. S., & Rosenthal, R. (1988). Synchrony, pseudosynchrony, and dissynchrony: Measuring the entrainment process in mother–infant interactions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 243–253.

Bernieri, F. J., & Rosenthal, R. (1991). Interpersonal coordination: Behavior matching and interactional synchrony. In R. S. Feldman & B. Rime (Eds.), Fundamentals of nonverbal behavior (pp. 401–432). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Buck, R., Losow, J. I., Murphy, M. M., & Costanzo, P. (1992). Social facilitation and inhibition of emotional expression and communication. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 962–968.

Cappella, J. N. (1981). Mutual influence in expressive behavior: Adult–adult and infant–infant dyadic interaction. Psychological Bulletin, 89, 101–132.

Charny, E. J. (1966). Psychosomatic manifestations of rapport in psychotherapy. Psychosomatic Medicine, 28, 305–315.

Condon, W. S. (1970). Method of micro-analysis of sound films of behavior. Behavior Research Methods and Instrumentation, 2, 51–54.

Condon, W. S., & Ogston, W. D. (1966). Sound film analysis of normal and pathological behavior patterns. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases, 143, 338–457.

Condon, W. S., & Sander, L. W. (1974). Synchrony demonstrated between movements of the neonate and adult speech. Child Development, 45, 456–462.

Gillis, J. S., Bernieri, F. J., & Wooten, E. (1995). The effects of stimulus medium and feedback on the judgment of rapport. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 63, 33–45.

Grahe, J. E., & Bernieri, F. J. (2002). Self-awareness of judgment policies of rapport. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 1407–1418.

Hall, J. A. (1984). Nonverbal sex differences: Communication accuracy and expressive style. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hall, J. A., & Bernieri, F. J. (2001). Interpersonal sensitivity: Theory and measurement. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Kimura, M., Yogo, M., & Daibo, I. (2004). Synchrony tendency in the conversation about emotional episodes: A measurement by “the pseudosynchrony experimental paradigm.” Japanese Journal of Interpersonal and Social Psychology, 4, 92–99.

Kimura, M., Yogo, M., & Daibo, I. (2005). Expressivity halo effect in the conversation about emotional episodes. Japanese Journal of Research on Emotions, 12, 12–23.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224–253.

Matarazzo, J. D., Saslow, G. W., Wiens, A. N., Weitman, M., & Allen, B. V. (1964). Interviewer head nodding and interviewee speech durations. Psychology: Theory, Research, and Practice, 1, 54–63.

Matsumoto, D., & Ekman, P. (1989). American–Japanese cultural differences in intensity ratings of facial expressions of emotion. Motivation and Emotion, 13, 143–157.

Nisbett, R. E. (2003). The geography of thought: How Asians and Westerners think differently...and why. New York: The Free Press.

Planalp, S. (1999). Communicating emotion: Social, moral, and culture processes. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Takai, J., & Ota, H. (1994). Assessing Japanese interpersonal communication competence. Japanese Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 33, 224–236.

Tickle-Degnen, L., & Rosenthal, R. (1987). Group rapport and nonverbal behavior. Review of Personality and Social Psychology, 9, 113–136.

Tronik, E. D., Als, H., & Brazelton, T. B. (1977). Mutuality in mother–infant interaction. Journal of Communication, 27, 74–79.

Wylie, L. (1985). Language learning and communication. The French Review, 53, 777–785.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kimura, M., Daibo, I. Interactional Synchrony in Conversations about Emotional Episodes: A Measurement by “the Between-Participants Pseudosynchrony Experimental Paradigm”. J Nonverbal Behav 30, 115–126 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-006-0011-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-006-0011-5