Abstract

It has repeatedly been shown that dispositional optimism, a generalized positive outcome expectancy, is associated with greater physical and psychological well-being. Coping has been proposed to mediate this purportedly causal relationship. From an expectancy-value perspective on motivation, optimists’ confidence leads them to tenaciously pursue goals. However, the ability to flexibly adjust goals might serve optimists’ ability to deal with adversity particularly well. This study investigated motivational coping (tenacious goal pursuit and flexible goal adjustment) as the mechanism linking dispositional optimism to several indices of well-being (general well-being, depression, anxiety and physical complaints) by means of a questionnaire study in the general population. Results of this study confirmed that motivational coping—primarily in the form of flexible goal adjustment—mediates the relationship between optimism and all indices of well-being except physical complaints. Furthermore, coping by flexibly adjusting one’s goals is generally a more prominent pathway to well-being than tenaciously pursuing those goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The role personality plays in determining well-being has long been a topic of interest in psychological research (Caspi et al. 2005). Well-being is a complex construct that has been defined in various ways (Ryan and Deci 2001). One personality factor that seems inextricably linked with greater well-being in a broad sense is optimism (Carver et al. 1994; Carver et al. 2010; Rasmussen et al. 2009; Scheier and Carver 1992). Moreover, in times of adversity, such as in response to chronic injuries, diseases or medical procedures, optimists consistently report fewer psychological and physical complaints (Carver et al. 2010; Rasmussen et al. 2009). Coping has been proposed as a potential mediator of these relationships (Carver et al. 2010; Scheier and Carver 1985, 1992; Scheier et al. 1986).

Dispositional optimism has been defined as a generalized positive outcome expectancy (Scheier and Carver 1985). Optimists generally expect good things to happen to them, while pessimists anticipate negative outcomes. According to the expectancy-value model of motivation, the combination of the outcome expectancy and the value of a goal determines goal-directed behaviour (Carver and Scheier 1998). It has been argued that optimists’ confidence about the future leads them to continue effort towards desired goals, even ‘when the going gets tough’. In contrast, pessimists’ tendency to doubt future outcomes facilitates a reduction in goal-directed effort and goal disengagement (Carver et al. 2010; Slutske et al. 2005). In line with the fundamental premises of the expectancy-value model of motivation, optimists have typically been described as approach or engagement copers (Carver et al. 2010; Solberg Nes and Segerstrom 2006). Pessimists, on the other hand, have been found to make greater use of avoidant or disengagement coping (Carver et al. 2010; Roth and Cohen 1986; Solberg Nes and Segerstrom 2006).

Although optimists’ tendency to pursue desired goals tenaciously has generally been related to indices of higher well-being, the adaptive nature of favourable beliefs and tenacity in goal pursuit has been argued (Carver et al. 2010). For instance, optimists appear reluctant to reduce efforts after poor outcomes when gambling (Gibson and Sanbonmatsu 2004). In general, optimists seem to experience more goal conflict (Segerstrom and Nes 2006). Moreover, overly optimistic expectations have been associated with a failure to recognize or act upon threat (Weinstein 1989).

In contrast to these observations, however, optimists are assumed to display great flexibility in coping and goal pursuit. It has been found that optimists switch flexibly between several coping strategies to meet the demands of the situation (Carver et al. 2010; Solberg Nes and Segerstrom 2006). Dispositional optimism has been linked to several measures of goal dis- and/or re-engagement (Brandtstädter and Renner 1990; Rasmussen et al. 2006; Solberg Nes and Segerstrom 2006; Wrosch and Scheier 2003). Aspinwall and Richter (1999), for example, found that optimists were more likely than pessimists to disengage from unsolvable anagrams in order to allocate their effort to solvable anagrams.

Although several classifications exist in the coping literature, the need for an emphasis on functional and motivational aspects within the study of coping has been argued (Skinner et al. 2003; Van Damme et al. 2008). Brandstädter and Renner (1990) proposed a dynamic perspective on coping. In their dual process model of coping, tenacious goal pursuit and flexible goal adjustment are introduced as two broad motivational coping strategies. Tenacious goal pursuit is an assimilative coping mode in which life circumstances are adjusted to reach a desired condition. Flexible goal adjustment, on the other hand, refers to the process of accommodation, in which personal preferences or goals are adjusted to meet the constraints of a situation.

These motivational coping tendencies have successfully explained higher quality of life in older age (Brandtstädter and Renner 1990) and in general (Wrosch and Scheier 2003; Wrosch et al. 2003). Motivational coping might mediate the relationship between dispositional optimism and well-being. Flexible goal adjustment especially seems to buffer the negative consequences of stressful circumstances (Schmitz et al. 1996). Since optimism has specifically been related to well-being despite adversity, flexible goal adjustment might be of particular importance with respect to explaining the relationship between optimism and well-being.

This study investigates the role of motivational coping in the association between dispositional optimism and well-being. We examine and compare the direct and indirect effects of optimism on four indices of well-being: general well-being, depression, anxiety and physical complaints, through two motivational coping strategies in a parallel multiple mediator model. We hypothesize that motivational coping (flexible goal adjustment and tenacious goal pursuit) mediates the effect of dispositional optimism on well-being. Furthermore, we hypothesize that the indirect effect of optimism on well-being is larger through flexible goal adjustment than through tenacious goal pursuit.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

The participants were 254 individuals (177, or 69 % female) with a mean age of 35.31 (SD = 15.04).Footnote 1 The recruitment strategy included flyers at Maastricht University and advertisements in regional newspapers. Fluency in the Dutch language and an age between 18 and 65 were necessary conditions to participate. Inclusion criteria were checked via email prior to participation. Participation was voluntarily, with a chance of winning an iPod or gift coupons by lottery as an incentive. In this sample, the reported levels of education were junior (16.5 %) or senior/academic education (35.8 %) and secondary (46.9 %) or primary education (0.8 %).

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Dispositional Optimism

The Dutch Version of the Life Orientation Test Revised (LOT-R) was used to measure dispositional optimism (Scheier et al. 1994). Dispositional optimism was measured by means of 3 positive and 3 negative items, such as ‘In uncertain times, I usually expect the best’ or ‘If something can go wrong for me, it will’. Four filler items are added to conceal the aim of the assessment. The response format used was a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (=strongly agree) to 5 (=strongly disagree). Reliability and validity of the LOT-R has been established as satisfactory (Scheier et al. 1994). The total score was computed as the average response to the positive and reversed negative items, such that higher scores reflect greater dispositional optimism (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83).Footnote 2 .

2.2.2 Tenacious Goal Pursuit and Flexible Goal Adjustment

Motivational coping was assessed by means of a Dutch translation of the flexible goal adjustment (FGA) and tenacious goal pursuit (TGP) scales (Brandtstädter and Renner 1990). Psychometric properties of the English version of the scales have been reported to be good (Brandtstädter and Renner 1990). Both scales consist of 15 items measuring assimilative and accommodative tendencies at a dispositional level. Items such as ‘I can be very obstinate in pursuing my goals’ or ‘After a serious disappointment, I soon turn to new tasks’ are used to measure accommodative (TGP) and assimilative (FGA) coping respectively. The items are scored on a scale ranging from 0 (= not agree at all) to 4 (= totally agree). In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for TGP and FGA were 0.82 and 0.86, respectively. Higher scores reflect greater tenacious goal pursuit and more flexible goal adjustment.

2.2.3 Well-being Questionnaire: General well-being

General well-being was measured with the 12-item Dutch Well-Being Questionnaire (W-BQ12; Bradley 2000; Pouwer et al. 2000; Riazi et al. 2006). The Dutch version of the W-BQ12 is shown to be a valid and reliable measure of well-being in people with diabetes (Pouwer et al. 2000). Although originally designed to be suitable for use by people with chronic diseases (avoiding somatic items), it can nevertheless be used as a generic measure for general well-being (Pouwer et al. 2000; Speight et al. 2007). The questionnaire consists of 12 items, which comprise three subscales of 4 items each. The ‘negative well-being’ subscale assesses (the absence of) negative feelings related to anxiety or depression. The ‘positive well-being’ subscale consists of items measuring feelings of happiness and satisfaction. In addition to these two subscales measuring hedonic aspects of well-being, the ‘energy’ subscale of the WBQ-12 measures a eudaimonic aspect of well-being (i.e. vitality). In this study only the total score was used as an indication of self-reported general well-being. All items were scored on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (= not at all) to 3 (= all the time). Individual items were reversed according to the guidelines and the average response was used in the analysis (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92). Higher scores on the scale reflect greater general well-being.

2.2.4 Anxiety and Depression

The Dutch version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Questionnaire (HADS) developed by Zigmond and Snaith (1983) was used in this study to measure anxiety and depression. Psychometric properties of both the English and Dutch version have been found to be satisfactory (Spinhoven et al. 1997; Zigmond and Snaith 1983). Both the depression and anxiety subscale consist of 7 items that are scored on a 4-point Likert scale. The average response to items in each subscale was used as the quantification of anxiety (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85) and depression (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87) in the analysis, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of anxiety/depression.

2.2.5 Physical Complaints

Participants were asked to indicate to what extent they experience a series of physical complaints. On the physical complaints list, the following answering format was used: 0 = never or hardly ever, 1 = <3 or 4 times a year, 2 = almost every month, 3 = almost every week, 4 = more than once a week. Items consisted of the following physical complaints: nausea, headache, back pain, fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, stomach-ache and dizziness. The average response across all items was used as a measure of the frequency of common physical complaints (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80).

2.3 Procedure

Participants who expressed interest in response to our recruitment efforts received additional information about the study by e-mail. They were informed that the study was being conducted in order to evaluate the quality of certain questionnaires. Detailed instructions about the online procedure were provided and qualifications for inclusion in the study were checked via email.

Participants were then directed to our assessment page, located in a secure online environment. Following the provision of informed consent, demographic variables were measured. Participants then completed several questionnaires in which each item was presented separately on screen. The procedure did not allow items to be skipped. Other questionnaires that are not part of the scope of this article were also included in this assessment battery. Total assessment time was 45–60 min.

2.4 Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficients between dispositional optimism, motivational coping strategies (flexible goal adjustment; tenacious goal pursuit) and indices of well-being (general well-being; depression; anxiety; physical complaints) were calculated.

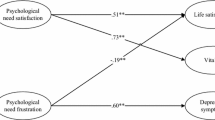

In order to test whether the relationship between dispositional optimism and well-being is mediated by motivational coping (hypothesis 1), an observed variable path analysis corresponding to Fig. 1 was conducted using Mplus v6.0 (Muthén and Muthén 2011). This model includes all possible direct and indirect effects of optimism on general well-being, anxiety, depression and physical complaints, with the indirect effects operating through the two motivational coping strategies. A model with multiple mediators such as this contains two specific indirect effects of optimism on each outcome, one through each motivational coping strategy, as well as a total indirect effect defined as the sum of the two specific indirect effects. As is widely-recommended (e.g., Hayes 2013; Hayes and Scharkow 2013), inference for indirect effects was based on bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals using 10,000 bootstrap samples. Mediation is established if the confidence interval for an indirect effect does not straddle zero.

To examine whether the indirect effect of optimism is significantly larger through flexible goal adjustment than through tenacious goal pursuit (hypothesis 2), these specific indirect effects were formally compared, for each outcome, also using a bootstrap confidence interval for the difference between indirect effects (see Hayes 2013, pp. 140–143; MacKinnon 2000; Preacher and Hayes 2008).

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics as well as correlation coefficients between dispositional optimism, motivational coping and indices of well-being are presented in Table 1. The correlations between dispositional optimism, motivational coping strategies (flexible goal adjustment and tenacious goal pursuit) and well-being (general well-being, depression, anxiety, and physical complaints) were all statistically significant. As expected, the relatively more optimistic participants scored higher in both tenacious goal pursuit and flexible goal adjustment. Furthermore, participants relatively higher in these motivational coping strategies reported greater general well-being, lower depression and anxiety, and fewer physical complaints.

3.2 Mediation Analysis

We hypothesized that dispositional optimism is related to indices of well-being and that these relationships are mediated by flexible goal adjustment and tenacious goal pursuit. The correlations between optimism and the four well-being measures in Table 1 substantiate that optimists tend to experience more well-being than those who are less optimistic.

The path analysis corresponding to Fig. 1 was conducted using maximum likelihood estimation with Mplus 6.0. In accordance with the recommendation of Preacher and Hayes (2008), the covariances between the errors in estimation of the mediators were freely estimated. We also freely estimated the covariances between the errors in estimation of each outcome.Footnote 3 Not depicted in Fig. 1, we included sex and age as controls in the model by adding paths from these covariates to all mediators and outcomes in order to eliminate any association between key variables in the model that could be attributed to sex differences or shared covariation with age.Footnote 4 The resulting model is saturated, meaning as many parameters are estimated as degrees of freedom available. Therefore, fit is necessarily perfect.

The model coefficients can be found in Tab. 2 and 3 provides the indirect effects of optimism through motivational coping along with bootstrap confidence intervals. The total indirect effect offers information about motivational coping (i.e., summed across the indirect effects through the two coping strategies) as a mediator. Specific indirect effects of flexible goal adjustment and tenacious goal pursuit describe mediation by the individual motivational coping tendencies. The direct effects (in the first row of Table 2) estimate the relationship between optimism and the well-being outcomes through mechanisms or processes (e.g., spuriousness) not explicitly modelled.

As can be seen from the total indirect effects of optimism in Table 3 (TGP + FGA), aggregated coping mechanisms significantly mediate the relationship between dispositional optimism and general well-being, anxiety, and depression, but not physical complaints. Based on the coefficients in Table 2 and the bootstrap confidence intervals for the total indirect effects, more optimistic participants tend to pursue goals more tenaciously, and are more inclined to adjust their goals based on the demands of the situation as compared to low optimistic participants. These strategies in turn are associated with increased general well-being and reduced anxiety and depression.

The total indirect effects aggregate across the specific indirect pathways of influence, and as discussed in Hayes (2013), they can mask or otherwise obscure the effects operating at the level of the specific mediators depending on the size and sign of those specific indirect effects. In a multiple mediator model, the specific indirect effects quantify the influence of one variable and another through a third while statistically holding constant the other mediators in the model. An examination of the specific indirect effects in Table 3 shows that the mediation of the effect of optimism on well-being operates primarily through flexible goal adjustment, with negative indirect effects on depression and anxiety and a positive indirect effect on general well-being. The only statistically significant specific indirect effect through tenacious goal pursuit was on general well-being, with optimism associated with more positive general well-being.

Finally, as can be seen in Table 2, the direct effect of optimism on well-being was statistically significant for all outcome variables, meaning that optimism is related to well-being after accounting for the indirect process through motivational coping. That is, holding differences in motivational coping constant, the more optimistic the greater well-being (higher general well-being and lower anxiety, depression, and physical symptoms).

3.3 Comparison of Indirect Effects

The prior analysis reveals evidence of an indirect effect of optimism on several measures of well-being primarily through flexible goal adjustment and not through tenacious goal pursuit. A difference in significance of indirect effects does not imply they are significantly different. A formal test of difference between these specific indirect effects (TGP–FGA) can be found in Table 3, along with bias-corrected 95 % confidence intervals for the differences. As can be seen, for general well-being, anxiety, and depression, the two specific indirect effects were statistically different (as the bootstrap confidence interval for the difference does not straddle zero), but they were not different for physical complaints. These results bolster our claim that of the two coping strategies we examined, flexible goal adjustment is the primary mechanism through which dispositional optimism influences well-being.

4 Discussion

The beneficial impact of dispositional optimism on physical and psychological well-being is well documented (Carver et al. 1994, 2010; Rasmussen et al. 2009; Scheier and Carver 1985, 1992). The relationships between dispositional optimism and general well-being, depression, anxiety and physical complaints adds to the available evidence establishing that optimists experience greater subjective well-being than pessimists. More importantly, however, this study provides new evidence regarding the mechanism by which this effect may operate. We sought to investigate two motivational coping strategies as the mechanism linking dispositional optimism and several indices of well-being, and found evidence consistent with mediation by motivational coping. Similar to what others have found (Brandtstädter and Renner 1990; Rasmussen et al. 2006; Solberg Nes and Segerstrom 2006; Wrosch and Scheier 2003; Wrosch et al. 2003), optimists in our study were more inclined than pessimists to pursue goals tenaciously while also flexibly adjusting goals based on the situation. Moreover, it was primarily flexible goal adjustment that seemed to translate into greater well-being. There was no indirect effect of optimism through tenacious goal pursuit except for one measure of well-being, and that indirect effect was smaller than the effect through flexible goal adjustment. These results underscore that motivational coping at least partially explains the relationship between dispositional optimism and certain indices of well-being (Carver et al. 1994, 2010; Rasmussen et al. 2009; Scheier and Carver 1992).

These results also confirm our hypothesis that the indirect effect of optimism on well-being would be larger through flexible goal adjustment than through tenacious goal pursuit. These results contribute to the conviction that flexible goal adjustment protects people from negative consequences in stressful circumstances and promotes quality of life (Schmitz et al. 1996; Wrosch and Scheier 2003; Wrosch et al. 2003). While these findings are consistent with research linking optimism and goal disengagement and reengagement (Brandtstädter and Renner 1990; Rasmussen et al. 2006; Wrosch and Scheier 2003; Wrosch et al. 2003), reconciling them with predictions from the expectancy-value model of motivation is challenging. In this framework, optimistic expectations by definition lead to well-being through continued goal attainment. However, our results attest to the greater importance of optimists’ flexibility instead of tenacity in the pursuit of goals towards well-being.

Our results invite speculations on the role of flexible goal adjustment in an expectancy-value framework of motivation. First of all, it is interesting that flexible goal adjustment has been described as a strategy to stay engaged instead of turning effort away. Adaptive self-regulation includes not only behavioural but also cognitive responses. Goal adjustment strategies, such as redefining values, goal conceptualisations and internal standards for evaluations of goal progress are actually engagement enhancing strategies (Carver and Scheier 2000). Secondly, it should be noted that goals are organised in a hierarchical structure (Carver and Scheier 1998). Disengagement of a behavioural goal on a lower level might therefore secure goal attainment on a higher level. The broadening effect of positive emotions and cognitions might support a focus on the bigger picture (Fredrickson 2001, 2004), thereby enhancing flexible goal pursuit. Finally, a discrepancy between general and specific optimistic expectations has been reported (Armor and Taylor 1998; Hanssen et al. 2013, 2014; Scheier and Carver 1992). Both generalized and specific expectations might influence goal-directed behaviour differently (Neff and Geers 2013). It is not inconceivable that generalized expectations influence the pursuit of higher order goals in particular.

Another area of research that might be helpful in understanding adaptive self-regulation in optimists is based on the principles of the Self Determination Theory (SDT; Deci and Ryan 2000). According to SDT, the type of motivation determines self-regulatory processes (Ryan and Deci 2000). Thompson and Gaudreau (2008) found that students with generalized positive expectations engage in academic activities mainly because of pleasure (intrinsic motivation), while the engagement of students with generalized negative expectations is based on extrinsic motivation. These latter findings provided evidence for the mediating role of self-determined motivation in the association of optimism/pessimism with coping (Thompson and Gaudreau 2008). The SDT-inspired Dualistic model of Passion (Vallerand et al. 2003) describes two types of passion for activities that seem closely linked to the two types of motivational coping in the dual process model of coping (Brandtstädter and Renner 1990). A harmonious passion, which results from an autonomous internalisation (linked to intrinsic motivation), fosters flexible engagement in the loved activity. An obsessive passion, which results from a controlled internalisation (linked to extrinsic motivation), leads to a rigid persistence of the important activity. The study of harmonious versus obsessive passion might lead to new insights regarding adaptive self-regulation in optimists.

A few important limitations should be noted. First, although the model we proposed and estimated is a causal one, with optimism purportedly influencing coping which in turn influences well-being, statistics cannot establish cause, and our data are merely correlational in nature. Experimental research can provide useful information about the way in which optimists pursue goals. Second, even after accounting for the contribution of motivational coping strategies, optimism was still related to well-being (i.e., the direct effects were statistically significant). This finding suggests the existence of additional processes linking dispositional optimism to well-being that our model does not account for. Third, this study was based on a general community sample rather than people who experience adversity in some form day after day. Replication using a sample of people who regularly experience adversity (such as chronic pain sufferers, cancer patients, and so forth) could provide more information about the role of flexibility in how optimists deal with stressful circumstances.

In conclusion, motivational coping seems to be one mechanism by which optimism can influence several aspects of well-being. We found that flexible goal adjustment stands out as a particularly important motivational coping strategy relative to the tenacious pursuit of goals that may in turn influence psychological well-being. Future research should focus on flexible goal adjustment as displayed by optimists in order to understand better how this coping strategy could facilitate the effectiveness of interventions aimed at dealing with adversity in life.

Notes

One male did not report his age. In the analyses we report, we imputed this participant’s missing age with the mean age for men (39.89 years).

There has been some debate in the literature whether the LOT-R is unidimensional or bidimensional with optimism and pessimism factors. We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis comparing a unidimensional to a bidimensional model and found that although the bidimensional model did fit better, the correlation between the two factors was −0.80. Thus, we treat the LOT-R as a unidimensional measure of optimism given the strong negative correlation between optimism and pessimism.

Fixing these covariances to zero resulted in a statistically significant reduction in fit, signifying the importance of allowing the remaining variance in these variables to correlate after accounting for their associations resulting from their determinants in the model.

Preliminary analyses revealed that males reported significantly higher depression, and fewer physical complaints than females, and older participants reported less optimism, lower tenacious goal pursuit, lower general well-being, and higher depression than younger participants.

References

Armor, D. A., & Taylor, S. E. (1998). Situated optimism: Specific outcome expectancies and self-regulation. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 30, pp. 309–379). New York: Academic Press.

Aspinwall, L. G., & Richter, L. (1999). Optimism and self-mastery predict more rapid disengagement from unsolvable tasks in the presence of alternatives. Motivation and Emotion, 23, 221–245.

Bradley, C. (2000). The 12-item Well-being Questionnaire. Origins, current state of development, and availability. Diabetic Medicine, 7, 445–451.

Brandtstädter, J., & Renner, G. (1990). Tenacious goal pursuit and flexible goal adjustment: Explication and age-related analysis of assimilative and accommodative strategies of coping. Psychology and Aging, 5, 58–67.

Carver, C. S., Pozo-Kaderman, C., Harris, S. D., Noriega, V., Scheier, M. F., Robinson, D. S., et al. (1994). Optimism versus pessimism predicts the quality of women’s adjustment to early stage breast cancer. Cancer, 73, 1213–1220.

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. (1998). On the Self-Regulation of Behavior. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (2000). Scaling back goals and recalibration of the affect system are processes in normal adaptive self-regulation: Understanding ‘response shift’ phenomena. Social Science and Medicine, 50, 1715–1722.

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Segerstrom, S. C. (2010). Optimism. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 879–889.

Caspi, A., Roberts, B. W., & Shiner, R. L. (2005). Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 453–484.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what”and “why”of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. The American Psychologist, 56, 218–226.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B Biological sciences, 359, 1367–1378.

Gibson, B., & Sanbonmatsu, D. M. (2004). Optimism, pessimism, and gambling: the downside of optimism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 149–160.

Hanssen, M. M., Peters, M. L., Vlaeyen, J. W., Meevissen, Y. M., & Vancleef, L. M. (2013). Optimism lowers pain: Evidence of the causal status and underlying mechanisms. Pain, 154, 53–58.

Hanssen, M. M., Vancleef, L. M., Vlaeyen, J. W., & Peters, M. L. (2014). More optimism, less pain! The influence of generalized and pain-specific expectations on experienced cold-pressor pain. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 37, 47–58.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: The Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F., & Scharkow, M. (2013). The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychological Science, 24, 1918–1927.

MacKinnon, D. P. (2000). Contrasts in multiple mediator models. In J. Rose, L. Chassin, C. C. Presson, & S. J. Sherman (Eds.), Multivariate applications in substance use and research: New methods for new questions (pp. 141–160). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2011). Mplus users guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles: Author.

Neff, L. A., & Geers, A. L. (2013). Optimistic expectations in early marriage: a resource or vulnerability for adaptive relationship functioning? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105, 38–60.

Pouwer, F., Snoek, F. J., van der Ploeg, H. M., Ader, H. J., & Heine, R. J. (2000). The well-being questionnaire: evidence for a three-factor structure with 12 items (W-BQ12). Psychological Medicine, 30, 455–462.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling methods for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891.

Rasmussen, H. N., Scheier, M. F., & Greenhouse, J. B. (2009). Optimism and physical health: a meta-analytic review. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 37, 239–256.

Rasmussen, H. N., Wrosch, C., Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (2006). Self-regulation processes and health: the importance of optimism and goal adjustment. Journal of Personality, 74, 1721–1747.

Riazi, A., Bradley, C., Barendse, S., & Ishii, H. (2006). Development of the Well-being questionnaire short-form in Japanese: the W-BQ12. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 4, 40.

Roth, S., & Cohen, L. J. (1986). Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress. American Psychologist, 41, 813–819.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54–67.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166.

Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology, 4, 219–247.

Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1992). Effects of optimism on psychological and physical well-being: Theoretical overview and empirical update. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 16, 201–228.

Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 1063–1078.

Scheier, M. F., Weintraub, J. K., & Carver, C. S. (1986). Coping with stress: Divergent strategies of optimists and pessimists. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1257–1264.

Schmitz, U., Saile, H., & Nilges, P. (1996). Coping with chronic pain: flexible goal adjustment as an interactive buffer against pain-related distress. Pain, 67, 41–51.

Segerstrom, S. C., & Nes, L. S. (2006). When Goals Conflict But People Prosper: The Case of Dispositional Optimism. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 675–693.

Skinner, E. A., Edge, K., Altman, J., & Sherwood, H. (2003). Searching for the structure of coping: a review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 216–269.

Slutske, W. S., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., & Poulton, R. (2005). Personality and problem gambling: a prospective study of a birth cohort of young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 769–775.

Solberg Nes, L., & Segerstrom, S. C. (2006). Dispositional optimism and coping: a meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10, 235–251.

Speight, J., McMillan, C., Barrington, M., & Victor, C. (2007). Review of scales of positive mental health validated for use with adults in the UK: Technical report. In (pp. 246). Edinburgh, Scotland.

Spinhoven, P., Ormel, J., Sloekers, P. P., Kempen, G. I., Speckens, A. E., & Van Hemert, A. M. (1997). A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychological Medicine, 27, 363–370.

Thompson, A., & Gaudreau, P. (2008). From optimism and pessimism to coping: The mediating role of academic motivation. International Journal of Stress Management, 15, 269–288.

Vallerand, R. J., Blanchard, C., Mageau, G. A., Koestner, R., Ratelle, C., Leonard, M., et al. (2003). Les passions de l’ame: on obsessive and harmonious passion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 756–767.

Van Damme, S., Crombez, G., & Eccleston, C. (2008). Coping with pain: a motivational perspective. Pain, 139, 1–4.

Weinstein, N. D. (1989). Optimistic biases about personal risks. Science, 246, 1232–1233.

Wrosch, C., & Scheier, M. F. (2003). Personality and quality of life: the importance of optimism and goal adjustment. Quality of Life Research, 12(Suppl 1), 59–72.

Wrosch, C., Scheier, M. F., Miller, G. E., Schulz, R., & Carver, C. S. (2003). Adaptive self-regulation of unattainable goals: goal disengagement, goal reengagement, and subjective well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 1494–1508.

Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67, 361–370.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Netherlands Organisation of Scientific Research [Grant number 453-07-005]. The contribution of Dr. Vancleef was sponsored by the Netherlands Organisation of Scientific Research [Grant number 451-09-026]. Johan W.S. Vlaeyen was supported by the Odysseus Grant ‘‘The Psychology of Pain and Disability Research Program’’ funded by the Research Foundation, Flanders, Belgium (FWO Vlaanderen, Belgium).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Hanssen, M.M., Vancleef, L.M.G., Vlaeyen, J.W.S. et al. Optimism, Motivational Coping and Well-being: Evidence Supporting the Importance of Flexible Goal Adjustment. J Happiness Stud 16, 1525–1537 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9572-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9572-x