Abstract

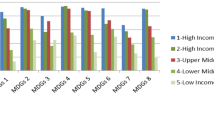

The article uses General Social Survey data (GSS) collected by Statistics Canada from 1986 to 2005 and experience sampling data (ESM) collected in 1985 and 2003 at the University of Waterloo to examine relationships between economic growth, household income, and subjective sense of well-being. The article puts to a test two propositions made by Easterlin (Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in Honor of Moses Abramovitz. Academic Press, New York, NY,1974), namely that personal and household incomes correlate positively with subjective well-being, but this does not apply to the relationship between subjective well-being and societal economic growth. Analyses of GSS data reported in this article support Easterlin’s findings. They show that higher household incomes correlate positively with respondents’ retrospective assessments of life satisfaction, but economic growth has not been accompanied by a corresponding rise of subjective well-being. Analyses of ESM data suggest that when relationships between household income and subjective well-being are measured by “experiential” measures (Csikszentmihalyi and Larson in J Nerv Ment Dis 175: 526–537, 1987), these relationships are not statistically significant and subjective valuations of well-being taper off at the top of the income pyramid.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Je ne sais rien de plus fatigant que d’être moralement très-heureux et materiellement très-malheureux. Honoré de Balzac, La Maison Nucingen (1838) http://www.feedbooks.com/book/1901/la-maison-nucingen.

www.jfklibrary.org/Historical+Resources/Archives/Reference+Desk/speeches/RFK/RFKSpeech68Mar18UKansas. For reasons underlying growing interest in subjective measurements of well-being see also Van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell (2004) and Layard (2005).

Different terms have been used to distinguish traditional recall assessments of subjective well-being (e.g. retrospective, remembered, global, reflective, cognitive) from the “on the go” assessments of daily life as it happens (process benefits, experienced utility, instant utility, momentary, affective). There is some ambiguity in all of these terms and hence a lack of consensus. We use the term “retrospective” (borrowed from Juster and Kahneman) in this article interchangeably with such terms as “generalised” or “recall” to emphasize the generality of traditional assessments of life satisfaction as opposed to situationally specific or instantaneous ESM valuations (How do I feel at the moment of the beep?). The policy implications of these two different measurements are commented upon in Section 7” of this article.

For further discussion of differences between retrospective and ‘instant utility’ measures of subjective well-being see Gershuny 2011.

ESM surveys were supported by grants from the Canadian Federal Department of Fitness and Amateur Sport and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

A glimpse at 2010 GSS data released after the submission of this article shows that life satisfaction ratings of employed adult population fell from 7.7 points in 2005 to 7.5 points in 2010 in spite of a 10 % growth of the PDI.

Unlike notions of “social comparison” or “relative income,” widely used in the discussion of the relationship between income and subjective well-being, the notion of “societal expectations” refers to a generalised longing for better socio-economic conditions, compared with the past rather than with other income groups or countries. The discourse about socio-political effects of rising and unfulfilled expectations goes back to Tocqueville (1856), Durkheim (1893), and Merton (1949).

Quelque différence qui paraisse entre les fortunes, il y a néanmoins une certaine compensation de biens et de maux qui les rend égales. Francois de La Rochefoucauld, Maximes (1664).

Pineo-Caroll-Moore socio-occupational classification of occupational groups is based on respondents’ occupation and their position within it. Professionals and high-level management, who ranked at the top of the occupational prestige scale, constituted in 1998 12 % of the employed population. Based on 2006 census data they earned around C$ 120,000–140,000 per annum. See 2006 Census of Canada: Topic-based tabulations. Employment income. www12.statcan.ca > Topic-based tabulations.

This phenomenon has been observed already by John Robinson (1977:162) in his analyses of the 1965–1966 U.S. time use data, when he wrote that “contrary to the positive value placed on free time in our society, greater life satisfaction generally was associated with less rather than more available free time.” Similar findings, based on Canadian GSS data, were reported by Zuzanek (2009).

According to Duesenberry (1952), utility obtained from consumption is not so much a function of the size of the expenditure or income, but rather of a comparison with the expenditure or income of other people, usually positioned in the higher income bracket, hence the notion of “relative income.”.

Effects of differences in framing SWB questions on survey findings are discussed by Graham (2009). See pp. 35 and 214.

The 2003 ESM survey shows that spending time alone correlates with affect negatively (“r” = − 0.10), while time spent in the company of children, friends or partners correlates with affect positively (“r” = 10, 12 and 0.17 respectively).

References

Abramovitz, M. (1959). The welfare interpretation of secular trends in national income and product. In M. Abramovitz, et al. (Eds.), The allocation of economic resources: Essays in honor of Bernard Francis Haley. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Alliger, G. M., & Williams, K. J. (1993). Using signal-contingent experience sampling methodology to study work in the field: A discussion and illustration examining task perceptions and mood. Personnel Psychology, 46(3), 525–549.

Andrews, F. M., & Whitey, S. B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being in America. New York, NY: Plenum.

Aristotle. (2009). The politics and the constitution of Athens. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Balzac, H. (1838) La Maison Nucingen, http://www.feedbooks.com/book/1901/la-maison-nucingen.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. (2004). Well-being overtime in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1359–1386.

Brooker, A. S. & Hyman, I. (2010). Time Use. A Report of the Canadian Index of Wellbeing (CIW). Toronto.

Campbell, A. (1972). Aspiration, satisfaction and fulfillment. In A. Campbell & P. Converse (Eds.), The human meaning of social change (pp. 441–446). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Campbell, A., Converse, P., & Rodgers, W. (1976). The quality of American life. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Cantril, A. H., & Roll, C. W., Jr. (1971). Hopes and fears of the American people. New York: Universe.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Csikszentmihalyi, I. (Eds.). (1988). Optimal experience: Psychological studies of flow in consciousness. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Hunter, J. (2003). Happiness in everyday life: The uses of experience sampling. Journal of Happiness Studies, 4, 185–199.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Larson, R. (1987). Validity and reliability of the experience sampling method. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 175(9), 526–537.

Deaton, A. (2008). Income, health, and well-being around the world: Evidence from the Gallup World Poll. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(2), 53–72.

DeVoe, S. E., & House, J. (2011). Time, money, and happiness: How does putting a price on time affect our ability to smell the roses? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2011.11.012.

Diener, E., Helliwell, J. F., & Kahneman, D. (Eds.). (2010). International differences in well-being. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Diener, E., Sandvik, E., Seidlitz, L., & Diener, M. (1993). The relationship between income and subjective well-being: Relative or absolute? Social Indicators Research, 28, 195–223.

Diener, E., & Suh, E. M. (1999). National differences in subjective well-being. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 434–450). New York, NY: Russell Sage.

Dow, G. K., & Juster, F. T. (1985). Goods, time and well-being: The joint dependence problem. In F. T. Juster & F. P. Stafford (Eds.), Time, goods, and well-being (pp. 397–413). Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan.

Drewnowski, J. (1970). Studies in the measurement of levels of living and welfare. Geneva: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development.

Duesenberry, J. S. (1952). Income, saving and the theory of consumer behaviour. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Durkheim, E. (1893). The division of labour in society. New York, NY: The Macmillan Company 1930.

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in Honor of Moses Abramovitz (pp. 98–125). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Easterlin, R. A. (1995). Will raising the income of all increase the happiness of all? Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 27(1), 35–47.

Easterlin, R.A. (2004) Feeding the illusion of growth and happiness: A reply to Hagerty and Veenhoven. http://www-bcf.usc.edu/~easterl/papers/HVcomment.pdf.

Easterlin, R.A. & Angelescu, L. (2009). Happiness and growth the world over: Time series evidence on the happiness-income paradox. IZA Discussion Paper (4060).

Easterlin, R. A., Angelescu, L., Switek, M., Sawangfa, O. & Zweig, J. S. (2010). The happiness-income paradox revisited. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), (doi:10.1073/pnas.1015962107).

Erikson, R. (1974). Welfare as a planning goal. Acta Sociologica, 17(3), 273–288.

Franklin, B. (1748) Advice to Young Tradesman Written by an Old One. Philadelphia: New Printing Office.

Galbraith, J. K. (1958). The affluent society. Boston: Houghton.

Gershuny, J. (2011). Time-use surveys and the measurement of national well-being. Oxford: University of Oxford, Centre for Time Use Research.

Graham, C. (2009). Happiness around the world. The paradox of happy peasants and miserable millionaires. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Graham, C. (2011). Does more money make you happier? Why so much debate? Applied Research Quality Life, 6, 219–239.

Hagerty, M. R. (2000). Social comparison of income in one’s community. Evidence from National Surveys of income and happiness. Journal of Personal and Social Psychology, 78(4), 764–771.

Hagerty, M. R., & Veenhoven, R. (2003). Wealth and happiness revisited—Growing national income does go with greater happiness. Social Indicators Research, 64, 1–27.

Hektner, J. M., Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Schmidt, J. (2002). Experience Sampling Method: Measuring the Quality of Everyday Life.

Helliwell, J. F. (2011). How can subjective well-being be improved? http://www.earth.columbia.edu/bhutan-conference-2011/sitefiles/John%2520Helliwell%2520-%2.

Homans, G. C. (1961). Social behavior: Its elementary forms. New York, NY: Harcourt.

Hurlburt, R. T., Lech, B. C., & Saltman, S. (1984). Random sampling of thought and mood. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 8, 263–275.

Juster, F. T. (1985). The validity and quality of time use estimates obtained from recall diaries. In F. T. Juster & F. P. Stafford (Eds.), Time, goods, and well-being (pp. 63–91). Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan.

Juster, F. T. (1990). Rethinking utility theory. The Journal of Behavioral Economics, 19(2), 155–179.

Juster, F. T., Courant, P. N., & Dow, G. K. (1981). A theoretical framework for the measurement of well-being. The Review of Income and Wealth, Series, 27(1), 1–31.

Juster, F. T., Ono, H., & Stafford, F. P. (2003). An assessment of alternative measures of time use. Sociological Methodology, 33(1), 19–54.

Kahneman, D., & Deaton, A. (2010). Does money buy happiness….or just a better life. Princeton: Princeton University. Mimeo.

Kahneman, D., & Krueger, A. B. (2006). Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(1), 2–24.

La Rochefoucauld, Francois. (1644). Réflexions ou sentences et maximes morales http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/14913.

Layard, R. (2005). Happiness: Lessons from a new science. New York, NY: Penguin Press.

Merton, R. K. (1949). Social theory and social structure. New York, NY: Free Press.

Noll, H. (2002). Social indicators and quality of life research: Background, achievements and current trends. In N. Genov (Ed.), Advances in sociological knowledge over half a century. Paris: International Social Science Council.

Robinson, J. (1977). How Americans use time. A social-psychological analysis of everyday behavior. New York, NY: Praeger.

Robinson, J. P. (1987). Microbehavioral approaches to monitoring human experience. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders, 175(9), 514–518.

Sacks, D. W., Stevenson, B. & Wolfers, J. (2010). Subjective well-being, income, economic development and growth. NBER Working Paper Series, (16441).

Shakespeare, W. (1623) As you like it. http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/1121/pg1121.txt.

Stevenson, B. & Wolfers, J. (2008) Economic growth and subjective well-being: Reassessing the Easterlin Paradox. http://bpp.wharton.upenn.edu/jwolfers/Papers/EasterlinParadox.pdf.

Stone, A. A., & Shiffman, S. (1992). Reflecting on the intensive measurement of stress, coping, and mood, with an emphasis on daily measures. Psychology and Health, 7, 115–129.

Strumilin, S. G. (1922) Problemy ekonomiki truda (Problems of the Economics of Labour). Moskva: Nauka (first published in 1922).

Stutzer, A. (2002) The Role of Income Aspirations in Individual Happiness. Working Papers Series ISSN 1424-0459, Institute of Empirical research in Economics, University of Zurich.

Tocqueville, A. (1856). The old regime and the revolution. New York, NY: Harper and Brothers.

Van den Haag, E. (1957). Of happiness and of despair we have no measure. In: Rosenberg B. & White D. M. Eds. Mass Culture. The Popular Arts in America. New York, NY: The Free Press of Glencoe (pp. 504–536).

Van Praag, B., & Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2004). Happiness quantified: Satisfaction calculus approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Veenhoven, R. (1991). Is happiness relative? Social Indicators Research, 24(1), 1–34.

Zuzanek, J. (2005). Adolescent time use and well-being from a comparative perspective. Loisir and Societe/Society and Leisure, 28(2), 379–423.

Zuzanek, J. (2009) Time use imbalance: Developmental and emotional costs. In: K. Matuska & Ch. R. Christiansen (Eds.) Life balance. Multidisciplinary theories and research. Bethesda MD: AOTA Press.

Zuzanek, J., & Mannell, R. (1993). Leisure behaviour and experiences as part of everyday life: The weekly rhythm. Loisir and Societe/Society and Leisure, 16(1), 31–57.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank anonymous reviewer # 1 for a series of constructive suggestions and Alexander Graham for assistance in preparing the manuscript of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zuzanek, J. Does Being Well-Off Make Us Happier? Problems of Measurement. J Happiness Stud 14, 795–815 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9356-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9356-0