Abstract

Despite the contributions of charismatic and transformational theories, their universal applicability has recently been called into question. Dovetailing this debate is a growing interest in followers. We contribute to these discussions by examining the impact of follower individual difference profiles on preferences for charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic styles of leading. Drawing on Weber’s (1924) taxonomy of managerial authority in its reconceptualized form as the charismatic-ideological-pragmatic (CIP) model, we conducted a vignette study in which 415 working adults first completed an online survey assessing their personality and work values. Eight weeks later, a second survey asked them to read a fictional scenario about an organization and three speeches depicting each leader’s style. Participants then indicated their leader preference, which we sought to predict using their personality and work values profiles. Results of discriminant function analyses indicated certain linear combinations of personality and work values variables discriminated between participants’ leader preferences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Little debate surrounds the vital impact of charismatic and transformational theories on the leadership literature. Influenced by the writings of Max Weber, arguably the foremost social theorist of the twentieth century, the emergence of these theories in the 1970s and 1980s (e.g., Bass 1985; Burns 1978; House 1977) reflected a watershed moment in leadership research—one that revived interest in the field following the failed attempts at identifying a set of universal leader traits and situational moderators. Indeed, across a wide range of outcomes, strong support exists for these theories in understanding outstanding leader behavior (Judge and Piccolo 2004).

Yet, questions have emerged over their universality and ability to capture the “full range” of leader behavior (e.g., Parr et al. 2013; Yukl 1999). In fact, Weber (1924), although aware of the potent effects that charisma can exert on followers, recognized its transient nature and the unique qualities of those affected by it. In his well-known work on managerial authority, he posited the existence of two other forms of leader behavior: traditional and legal-rational. The former is guided by an adherence to tradition, the latter by a formalistic belief in the law and rational appeal. For Weber, these styles of leading were equally valuable to organizational life.

In order to revitalize Weber’s taxonomy, recent research on the charismatic-ideological-pragmatic (CIP) model has examined similarities and differences between affective, vision-based influence and more traditional, belief-centered and rational, problem-focused forms of leading (e.g., Hunter et al. 2011; Ligon et al. 2008; Mumford 2006). Given the debate over the universality of charismatic and transformational theories, the CIP model is timely in that it offers more balance to the literature by highlighting the multiple paths by which leaders may strongly influence the individuals and groups they lead.

Based on the CIP model, the present study seeks to provide a quantitative and qualitative investigation of preferences for charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic styles of leading using follower personality and work values profiles as predictors. Although differences between these styles exist across contexts, we focus on conditions of crisis when they are most prominent (Mumford 2006). We make three contributions to the literature. First, using a follower-centric lens, we build on recent studies (e.g. Li et al. 2013; Parr et al. 2013) that highlight contingencies on the common view that charismatic and transformational behaviors are universally impactful. We theorize for whom charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic styles may be most influential and contrast the types of people who may prefer a charismatic style versus other forms of leading.

Second, by examining profiles of individuals who may be most attracted to charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic styles of leading, we expand on previous studies that have focused on specific personal characteristics (e.g., extraversion) as they relate to perceptions of charismatic and transformational behaviors (e.g., Felfe and Schyns 2006, 2010; Schyns and Felfe 2006; Schyns and Sanders 2007) and people’s implicit beliefs about charisma as an ideal leader trait (e.g., Keller 1999). That is, we take a broader approach that seeks to provide a comparative analysis of how different types of followers may react differently to three different styles of leading. In so doing, we also fill a void in CIP research by exploring its follower side, which remains unstudied to date.

Third, we contribute to research on followers (e.g., Carsten et al. 2010; Thoroughgood et al. 2012). Although there are no leaders or leadership without followers (Hollander 1993), the leadership literature is largely leader-centric, focusing on leader traits and behaviors and often depicting followers as passive recipients of leaders’ influence. Much less is known about follower characteristics or how they form unique profiles that influence reactions to different styles of leading. Borrowing from Klein and House (1995), leadership is a social process requiring a spark (leader), flammable material (susceptible followers), and oxygen (conducive context). We seek to identify what makes certain followers “flammable” in relation to three outstanding forms of leading.

Theoretical Foundations

Max Weber, the famous German sociologist, is known for his influence on modern social science. Perhaps his greatest contribution is his theory of management authority. Weber (1924) theorized that leader behavior can take three forms: charismatic, traditional, and legal-rational. These styles align with the C, I, and P in Mumford’s (2006) CIP model, respectively. A traditional style seeks to protect traditional values and institutions in order to preserve order and stability. In turn, a legal-rational style stresses pragmatism, which Weber believed was a driving force in bureaucracies. Finally, a charismatic style entails a leader’s perceived possession of extraordinary qualities and focus on breaking down bureaucracies via inspiring oratory and an idealized vision of the future.

Today, Weber’s taxonomy, in its reformulated form as the CIP model, is well supported by research (e.g., Bedell-Avers et al. 2008; Hunter et al. 2011; Mumford et al. 2008). Mumford’s (2006) six historiometric studies of 120 historical leaders revealed that charismatic, ideological and pragmatic leaders, across performance criteria, did not show performance differences—thus highlighting that there are multiple paths to becoming an outstanding leader and that research can profit from exploring these other pathways in addition to the well-studied charismatic path.

Overview of the CIP Model

Although stylistic differences between charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic leaders can be observed across contexts, CIP theory suggests these differences are most salient during times of instability when internal or external events threaten a social system’s performance and survival (Mumford 2006). Such conditions disrupt normal life, creating anxiety among system members. A leader’s sense-making, or prescriptive mental model, thus serves to alleviate stress by offering clarity about a group’s direction and a basis for goal pursuit (Shamir and Howell 1999).

Prescriptive models are based on a leader’s interpretation of the situation or descriptive mental model. Descriptive models are cognitive schemas that shape leaders’ perceptions of the environment. Leaders apply these heuristics to reduce the numerous causal variables related to a crisis into more manageable elements. What distinguishes outstanding leaders is their ability to integrate and reorganize descriptive models into prescriptive strategies for crisis resolution. Charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic leaders differ based on their descriptive models, creating variation in the prescriptive models they offer followers. Below, we discuss these distinctions (see Table 1).

Charismatic

The hallmark of a charismatic style is an emotionally evocative, imagery-laden vision of the future—a future radically different from the status quo (Conger and Kanungo 1987). It involves inspiring oratory to build a coalition of followers, as well as unconventional behavior and risk-taking. Charismatic leaders focus on positive events and goals, while pointing to negative aspects of the current system. They support new ideas and programs and empower followers by emphasizing trust, support, and teamwork. Such leaders set high goals and instill confidence in followers to reach them. Finally, charismatics view events as within their control and build commitment to their vision by promoting a collective identity (Shamir et al. 1993).Footnote 1

Ideological

An ideological style also involves an emotionally arousing vision; yet, such visions focus on an idealized past and a return to prior routines (Mumford 2006). Ideological leaders’ visions focus on preserving traditional values in order to maintain order and stability. They stress ideology over inspiring oratory and use their strong beliefs to guide their decisions during crises. Ideologues appeal to followers by pointing to a group’s history and prior status. Unlike charismatics, their speeches focus more on negative images of a system gone wrong to spur action. Thus, they rely on appeals marked by negative affect, aggression, confrontation, and propaganda. Ideologues grant influence to followers who fulfill their duties and reflect the group’s values, but expect conformity and punish those deviating from group norms (Ligon et al. 2008).

Pragmatic

A pragmatic style does not focus on vision articulation, but rather rational problem-solving that targets present circumstances (Mumford 2006). Pragmatic leaders cut to the heart of a problem and scan the situation for data to be used in their analysis. They employ adaptive strategies based on situational demands and focus on malleable goals that change when available data suggest a strategy is not working. Pragmatics stress rational persuasion, position clarification, and descriptions of paths to goal attainment. They do not rely on emotional appeals, but rather utilize balanced strategies grounded in expertise that appeal to followers’ desire for problem-focused action. Finally, pragmatics emphasize performance with followers; they allow autonomy and respect followers’ concerns, but focus on negotiation (Bedell-Avers et al. 2009).Footnote 2

Follower Characteristics and Leader Preferences

Despite only a handful of studies on the moderating effects of follower characteristics (e.g., Ehrhart and Klein 2001; Jung and Avolio 1999; Li et al. 2013; Wofford et al. 2001), the notion that attributes of followers influence a leader’s acceptance is not new. Contingency models (e.g. House 1971; Kerr and Jermier 1978) suggest follower characteristics may accentuate, attenuate, or neutralize the impact of a leader’s actions. Similarly, charisma is an attributional process that depends on follower perceptions (Conger and Kanungo 1987). Based on French and Raven (1959), Barbuto (2000) suggested influence depends on followers’ instant reactions to influence attempts. The effects of these “influence triggers” on compliance, in turn, depend on follower motivations.

Three overlapping theoretical explanations offer insight regarding the role of follower characteristics in shaping reactions to leaders. First, previous studies (e.g., Engle and Lord 1997; Liden et al. 1993; Keller 1999) point to a leader’s perceived similarity. The premise of similarity-attraction is that individuals prefer others who hold similar attitudes, values, and traits (Byrne 1971). Perceptions of similarity reinforce our beliefs, reduce dissonance, and stabilize the self-concept. Second, implicit leader theories (ILTs), or the cognitive structures specifying ideal traits and behaviors of leaders (Lord et al. 1984), influence reactions to leaders. ILTs develop from interactions, events, and experiences with leaders and aid in understanding and reacting to them (Epitropaki and Martin 2004). When a person “fits” our leader prototype, we classify them as a leader and grant them influence. Third, social projection theory provides a link between similarity-attraction and ILTs. It highlights the tendency to project one’s thoughts, preferences, and behaviors onto others (Cronbach 1955), leading to an overestimation that they will think and behave similarly across situations. Projection results from the lack of information we have about others, making the self a logical anchor from which to judge them (Epley et al. 2004). Assuming that others will think and behave similarly may also help sustain a positive self-image. Thus, people may not only prefer leaders who are seen as similar, but project their traits onto their images of a prototypical leader (Keller 1999). That is, ILTs may be a reflection of oneself.

In sum, these approaches point to the importance of followers’ perceived compatibility with a leader and their style of leading. While a few studies have used these theories to explain how isolated follower attributes influence perceptions of charisma (e.g. Ehrhart and Klein 2001; Felfe and Schyns 2010), few have explored how different constellations of characteristics shape preferences for different styles of leading. We address this gap by exploring how different types of followers may hold different preferences for charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic leaders.

The CIP Model and Follower Personality Profiles

Preference for a Charismatic Style of Leading

Consistent with prior work (e.g., Felfe and Schyns 2006; Keller 1999), we expected that a person high on extraversion, agreeableness, and openness and low on neuroticism would prefer a charismatic style. Because charismatic leaders are outgoing, assertive, and enthusiastic (Judge and Bono 2000), they may appeal to extraverted followers who are also sociable, dominant, and energetic. Indeed, extraverts tend to believe that charisma is an ideal quality in a leader (Keller 1999). Further, extraversion has a positive emotional core (e.g., Larsen and Ketelaar 1991), with extraverts reacting to positive stimuli with more positive affect. Thus, a charismatic’s positive emotional expressions may elicit more positive emotional reactions in extraverts. Their actions may also align with the positive lens through which less neurotic people view their social worlds. However, an ideologue’s hostile rhetoric is likely to fall in contrast to a less neurotic follower’s worldview, while a pragmatic may be unattractive due to their unemotional nature altogether.

Agreeable individuals focus on creating positive social relationships; they are courteous, cooperative, sympathetic, and tolerant (McCrae and Costa 1986). Because charismatic leaders are collaborative, sensitive to follower needs, and concerned with fostering positive relationships, they will likely appeal to agreeable followers. Yet, because agreeable people evade conflict and expect civil treatment (Graziano et al. 1996), they may react less favorably to an ideologue’s confrontational tactics, sharp rhetoric, and lesser focus on follower needs. Moreover, because pragmatics avoid emotional closeness to foster rational analysis, they may be less appealing to agreeable followers. Finally, those high on openness are curious, broad-minded, and comfortable with change (Costa and McCrae 1992). As such, they may be attracted to a charismatic’s focus on change and new ideas. Yet, they may perceive an ideological leader as overly insular given their rigid devotion to ideology and focus on a limited set of past-oriented goals (Hunter et al. 2011).

Preferences for charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic leaders may also vary based on followers’ temporal focus. Temporal focus is the degree to which people devote attention to the past, present, and future (Shipp et al. 2009). It is important given that it is linked to sense-making (Weick 1979), emotion (Wilson and Ross 2003), motivation (Fried and Slowik 2004), and decision-making (Das 1987). Future-focused followers may prefer charismatic leaders given their future-oriented visions and perceive these leaders’ temporal lens as similar to their own. Future focus is also related to positive affect and optimism (Shipp et al. 2009), qualities likely to be related to preference for the hope-infused messages of charismatic leaders.

In sum, because charismatics (a) are extraverted and articulate an emotionally evocative, inspirational vision of the future; (b) are collaborative, sensitive to follower needs, and interested in developing followers; and (c) are open to new ideas that challenge the status quo, they should appeal to followers who are also gregarious and prone to positive emotions, who value civility, collaboration, and positive social relationships, and who are open to change and new solutions.

Hypothesis 1

Relative to those who prefer an ideological or pragmatic style of leading, people who prefer a charismatic style possess a personality profile marked by higher (a) extraversion, (b) agreeableness, (c) openness, and (d) future focus and lower (e) neuroticism.

Preference for an Ideological Style of Leading

In contrast, ideological leaders may appeal to individuals high on neuroticism and low on agreeableness and openness. Given neurotic people hold negative explanatory styles (Judge et al. 2003), they may perceive an ideological leader’s negative emotional displays and sense-making activities as similar to their own cognitive style. Further, ideologues’ hostility toward out-groups may attract neurotic people who similarly project their negative emotions onto others. Indeed, neuroticism is related to blame attributions (Kuppens and Van Mechelen 2007) and displaced aggression (Denson et al. 2006). However, neurotic people may distrust a charismatic leader’s optimism and emphasis on follower needs and be less likely to prefer a pragmatic leader given they are guided more by emotions than logic (Morelli and Andrews 1980; Pacini and Epstein 1999).

Research further indicates followers low on agreeableness may actually react positively to leaders’ negative emotions (e.g., anger) (Van Kleef et al. 2010). Because disagreeable people are argumentative and cynical of others’ motives, they expect less civility and are less sensitive to inconsiderate behavior (Graziano et al. 1996). Thus, followers who are less focused on social harmony may not only view an ideologue’s brusqueness as sincere and similar to themselves, but may accept it given social conflict is less distracting and more motivating to them (Van Kleef et al. 2010). Yet, disagreeable followers may be skeptical of a charismatic leader’s affability and view such leaders as overly willing to appease others. They may also view a pragmatic leader as too socially flexible and willing to sell out their values to achieve goals (Bedell-Avers et al. 2009).

Because ideologues stress order and stability rather than change, they may also attract followers low on openness. Indeed, a lack of openness is related to risk aversion and resistance to change (Oreg 2003). Conversely, followers low on openness may resist a charismatic’s focus on change or disagree with a pragmatic leader’s malleable plans, which may change if strategic.

In terms of other constructs, those high on authoritarianism hold strong values stressing obedience to authority, a rigid devotion to in-group norms and an intolerance of out-groups and rule breakers (Altemeyer, 1988). They are likely to show unconditional respect for authorities, traditions, and institutions and support leaders who punish norm violators (Altemeyer, 1981). As followers, they may identify with ideological leaders who support tradition, create in- and out-groups, and demand obedience. Given their traditional values and hierarchical attitudes, they may also rely more on internal values than on how they are treated when responding to a leader (Li et al. 2013). Thus, they may be unmoved by a charismatic’s focus on developing close relationships with and empowering followers. They may also react critically to a charismatic’s change-oriented vision or to a pragmatic’s willingness to forfeit group values for strategic goals.

Authoritarians also tend to possess a rigid cognitive style marked by an intolerance of ambiguity (Van Hiel et al. 2004). Cognitively rigid people are less motivated to process complex information and tend to support legitimate authorities that also focus on clarity and order (Jost et al. 2003). Given ideologues support known solutions to organizational problems, which are easy to understand and geared toward preserving stability, rigid followers should identify with them. In contrast, charismatics may elicit anxiety in such followers, who view their openness to change and uncertainty as threatening. Given pragmatics may endorse sudden shifts in strategy based on the situation, they may also produce anxiety in followers who resist changes in plans.

Finally, those preferring an ideologue’s focus on tradition and established solutions are likely to have a past temporal lens. For past-focused individuals, time and events are believed to repeat themselves, resulting in perceived similarities between the past, present, and future (Ji et al. 2009). Thus, present or future problems are viewed as resolvable by following time-honored approaches (Brislin and Kim 2003). Given this cyclical perception of time, the past is treasured and traditions are respected. Thus, past-focused followers may identify with the known solutions of an ideologue. A past focus is also related to lower optimism, an external locus of control, and negative affect (Shipp et al. 2009), which are all linked to ideological leaders (Mumford 2006).

Taken together, because ideological leaders (a) articulate an emotionally evocative vision that relies on negative emotions and in-group-out-group distinctions, (b) are more confrontational and less sensitive to follower needs, and (c) seek to preserve past norms, values, and traditions, they may appeal to followers who are disposed to negative emotions, who value blunt rhetoric and are more tolerant of insensitive behavior, and who are more dogmatic and authoritarian.

Hypothesis 2

Relative to those who prefer a charismatic or pragmatic style of leading, people who prefer an ideological style possess a personality profile marked by higher (a) neuroticism, (b) authoritarianism, (c) cognitive rigidity, and (d) past focus and lower (e) agreeableness and (f) openness.

Preference for a Pragmatic Style of Leading

We expected followers high on openness and conscientiousness and low on neuroticism and extraversion would prefer a pragmatic leader. Given their focus on adaptability, pragmatic leaders are tolerant of ambiguity and change course when the situation dictates. Thus, like those preferring a charismatic leader, those who prefer a pragmatic may also be open and flexible in response to sudden changes in strategy. Furthermore, because conscientious people are planful and thorough, they may view pragmatic leaders, who carefully scrutinize available data before deciding on a given course of action, as similar to themselves. Conscientiousness and openness are also related to rational cognition (Pacini and Epstein 1999). As such, followers high on these factors may view a pragmatic leader’s style as similar to their own flexible, methodical nature.

Further, followers low on extraversion may be less attracted to a charismatic’s energetic and expressive style and more attracted to a pragmatic’s more measured approach. Assuming these followers will react more favorably to logical appeals, they may be lower on neuroticism and higher on rational mindedness. Cognitive-experiential self-theory (CEST; Epstein 1994) suggests people experience differences between what they think and feel, which stem from two information-processing systems: experiential and rational. The latter is an inferential system based in modes of reasoning that are conscious, analytical, and affect-free. The former is a learning system that is preconscious, automatic, and affect laden (Pacini and Epstein 1999). CEST suggests these systems act independently and interactively to shape behavior and vary in their activation in people. Thus, those with dominant rational thinking styles, who are less motivated by emotion, may identify with pragmatic leaders who focus on logic and deemphasize emotion.

Finally, given pragmatic leaders place a strong emphasis on solving current problems, in contrast to charismatic leaders’ focus on the future and ideological leaders’ focus on the past, followers with a present focus should identify with pragmatic leaders’ orientation to the present.

Overall, because pragmatic leaders (a) are willing to adjust their strategies in response to changing situational conditions, (b) are methodical and measured in their approaches, and (c) are focused on solving present problems, they may appeal to followers who are also adaptable and comfortable with change, logical in their problem-solving, and oriented to the present moment.

Hypothesis 3

Relative to those who prefer a charismatic or ideological style of leading, people who prefer a pragmatic style possess a personality profile marked higher (a) openness, (b) conscientiousness, (c) rational mindedness, and (d) present focus and lower (e) extraversion and (f) neuroticism.

The CIP Model and Follower Work Values Profiles

Preference for a Charismatic Style of Leading

A charismatic leader’s focus on collaboration is likely to appeal to followers who value teamwork. Indeed, Ehrhart and Klein (2001) found that those valuing participation and working for mutual benefit tended to prefer a charismatic leader. Given ideologues emphasize hierarchy, control, and obedience, while pragmatics emphasize autonomy, they may appeal less to team-oriented followers. Team-oriented followers may also hold weaker values for autonomy and competition, and thus a charismatic’s focus on unity and cooperation may align with their values.

Finally, given a charismatic style is oriented around change, which entails ambiguity and risk taking, those with a weaker value for stability may feel comfortable with and stimulated by this form of leading. Those caring less about stability tend to engage in sensation-seeking and prefer changes in their environment (Zuckerman and Link 1968). These individuals may be less attracted to an ideological style of leading, given its focus on preserving the status quo, or a pragmatic style, which may support aspects of the status quo when strategically opportunistic.

In sum, because charismatic leaders (a) promote collaboration and a sense of collective identity and (b) support ideas that challenge the status quo, they should appeal to followers who prefer working cooperatively in teams and who are comfortable in unstable work environments.

Hypothesis 4

Relative to those who prefer an ideological or pragmatic style of leading, people who prefer a charismatic style possess a work values profile marked by a stronger value for (a) teamwork and weaker values for (b) autonomy, (c) competition, and (d) stability.

Preference for an Ideological Style of Leading

Authoritarians, perhaps due to their needs for certainty and stability, tend to obey strong authority figures at the expense of autonomy (Thoroughgood et al. 2012). Given ideologues focus on reestablishing order and demand conformity to in-group norms and values (Ligon et al. 2008), they may appeal to followers with a greater value for stability but a weaker value for autonomy.

Moreover, ideological leaders recruit a close cadre of like-minded followers who identify with their focus on returning to a group’s previous status (Mumford 2006). Thus, similar to charismatic leaders, they may attract those who value teamwork more and competition with in-group members less. For such followers, a group’s values are strongly linked to their identities. As such, their self-esteem likely depends on the group’s relative standing with out-group rivals (Howell and Shamir 2005). Indeed, research suggests authoritarians are willing to sacrifice their own goals for the in-group’s and support competition with out-groups (Triandis and Gelfand 1998). Thus, individuals who identify with ideologues may value working cooperatively with in-group members to accomplish group goals—as long as they remain committed to the group’s values.

Taken together, because ideological leaders (a) promote stability and order and (b) require conformity to in-group norms and values, they should attract followers who also value stability and who will work cooperatively with others to support the in-group’s values and traditions.

Hypothesis 5

Relative to those who prefer a charismatic or pragmatic style of leading, people who prefer an ideological style possess a work values profile marked by stronger values for (a) stability and (b) teamwork and weaker values for (c) autonomy and (d) competition.

Preference for a Pragmatic Style of Leading

In contrast to a charismatic leader’s focus on group cohesion and an ideological leader’s focus on conformity, pragmatic leaders support follower independence as a means of fostering diverse views and reducing groupthink (Mumford 2006). Thus, followers who value autonomy and the ability to influence their groups’ decisions may identify more with a pragmatic leader.

More independent followers might also prefer greater competition and less teamwork. Those valuing autonomy and self-reliance tend to value competitive success, show less concern for and weaker bonds to in-groups and believe groups are productive when members pursue self-interests (Triandis and Gelfand 1998; Wagner 1995). Given pragmatics stress opportunism, are willing to manipulate situations to gain a competitive advantage, and appeal to followers’ functional desires (Bedell et al. 2006), they may attract individualistic followers who focus on personal achievement and competition. As alluded to earlier, pragmatics may also attract those with a weak need for stability given such individuals must embrace sudden changes in strategy.

Overall, because pragmatic leaders (a) stress follower autonomy over group cohesion, (b) focus on strategic opportunism to secure a competitive advantage, and (c) change their strategies when needed, they may appeal to those who are more independent, competitive, and adaptable.

Hypothesis 6

Relative to those who prefer a charismatic or ideological style of leading, people who prefer a pragmatic style possess a work values profile marked by stronger values for (a) autonomy and (b) competition and weaker values for (c) teamwork and (d) stability.

Method

Participants and Procedure

This study used a sample of 445 working adults (M age = 36.65, SD = 5.31; 64.6% female) from a masters HR program at a university in the northeast of the United States. It was mainly Caucasian (81.3%), followed by African-American (7.7%), Hispanic (3.8%), and “other” (7.0%). Participants were working full or part-time and had, on average, 15.50 (SD = 5.12) years of work experience. They represented various industries (e.g., business, 29.5%; healthcare, 17.9%). In exchange for their participation, individuals were given course credit. To further incentivize participants, we also entered individuals who completed the surveys into a raffle for a US$500 Amazon gift card.

Data were collected online at two time points, separated by 8 weeks. Using a design employed by Ehrhart and Klein (2001), at time 1, participants completed a survey containing demographic and predictor measures. At time 2, they logged on to a second survey and read a description of an organization going through a crisis in which it was revealed that the CEO and top management team were embezzling money from the company. They were asked to imagine themselves as regional managers and informed that their task would be to give their vote to the board on who they preferred to be the new CEO. In random order, they were given statements from the three candidates describing their plan to resolve the crisis and their style of leading.

Subsequently, participants were asked to select the leader they preferred to be the next CEO. Responses to this leader choice item were used as the criterion in our discriminant function analyses, which were used to classify participants into personality and work values profiles. To garner further insight, we asked participants to list adjectives to describe the three leaders and to explain their leader choices. We also asked them to respond to a set of Likert-type items that assessed their perceived similarity to each of the leaders. We included this measure to examine the degree to which perceived similarity was related to participants’ overall leader selections.

To screen out those who may have paid less than adequate attention to the stimulus materials, participants responded to three questions that asked the name of the organization in the scenario, its circumstances, and what it was doing to address these conditions. Those who failed to answer all of the questions correctly were removed from the analysis (final N = 415).

Time 1: Independent and Control Variables

All variables were assessed on a 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 Strongly agree) Likert scale.

Big Five Traits

The Big Five were measured with the 44-item Big Five Inventory (John et al. 1991). Extraversion was measured with eight items (e.g., “I am talkative.”) (α = .84); openness with 10 items (e.g., “I’m curious about many different things.”) (α = .82); conscientiousness with nine items (e.g., “I do a thorough job.”) (α = .77); agreeableness with nine items (e.g., “I have a forgiving nature.”) (α = .77); and neuroticism with eight items (e.g., “I can be moody.”) (α = .81).

Authoritarianism

Zakrisson’s (2005) 15-item measure assessed authoritarianism (e.g., “The ‘old-fashioned ways’ and ‘old-fashioned values’ still show the best way to live.”) (α = .84).

Cognitive Rigidity

Four items from Oreg’s (2003) study were used to measure cognitive rigidity (α = .77) (e.g., “Once I have come to a conclusion, I am not likely to change my mind.”).

Rational Mindedness

Pacini and Epstein’s (1999) ten-item measure was used to assess rational mindedness (α = .90) (e.g., “I have no problem thinking things through carefully”).

Temporal Focus

Shipp et al. (2009) measures assessed temporal foci. The past-focused scale (α = .92) comprises four items (e.g., “I replay memories of the past in my mind”); the current focus scale (α = .76) consists of four items (e.g., “My mind is on the here and now”); and the future-focused scale (α = .82) includes four items (e.g., “I focus on my future”).

Work Values

Work values were measured with Berings et al.’s (2004) scales [Autonomy: four items (e.g., “It is important …” “… that I’m able to work independently most of the time.”) (α = .82); Teamwork: five items (e.g., “… that I be able to work in a team on a regular basis.”) (α = .86); Competition: five items (e.g., “… that my contributions are clearly marked as my own.”) (α = .74); and Stability: four items (e.g., “… for things to be changed only when strictly required.”) (α = .72)].

Demographic Variables

Consistent with previous studies of follower characteristics (e.g., Erhart and Klein 2001), we controlled for participants’ age, gender, and years of work experience.

Time 2: Stimulus Materials and Dependent Variables

Development of Study Materials

At time 2, participants were given an introduction to Big Buddies, a nonprofit focused on creating mentoring relationships between volunteers and children in need. Because the emergence of charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic leaders may be influenced by the organizational context, we chose a nonprofit in order to minimize, as much as possible, any contextual advantages afforded to a given leader. Specifically, Mumford (2006) noted that while charismatic leaders can emerge across a range of contexts, pragmatic leaders tend to emerge in business. In turn, ideological leaders are found more in nonprofit and political settings given the stronger values-based missions of such organizations. We consulted with ten CIP experts who suggested a nonprofit on the basis that it would (a) allow each leader to equally show their strengths and (b) enhance the study’s generalizability to more traditional workplaces.Footnote 3

Next, participants read about the crisis at Big Buddies. They were informed that auditors had revealed that top managers had embezzled money from organizational funds and that the scandal had led to a 47.2% decline in donations and a loss in donor trust. To cover rising costs and loss of donations, 360 employees were laid off, producing anxiety among the staff. To foster trust in top leaders, the Board of Directors were asking those in regional manager roles and up to vote on the candidate that they preferred to be the next CEO. As a new regional director, participants read descriptions of each person’s style of leading and plan to resolve the crisis.

Using prior descriptions (Mumford 2006), three passages, each three paragraphs long (425 words), were created to capture the prescriptive models of the three leader styles. Equal portions of each passage were devoted to the dimensions distinguishing the leaders’ prescriptive model. For example, the second paragraph differentiated the leaders based on the nature and outcomes sought. The charismatic described multiple positive goals; the ideologue described a limited set of transcendent goals; and the pragmatic discussed malleable goals (see Appendix A).

We asked ten people, each with a Ph.D. in I/O Psychology and experience with the CIP model, to offer feedback on the fictional scenario and the three passages, which were used to make needed changes. The passages’ content validity was also assessed with a sort task. Fifteen grad assistants were given descriptions of the leaders’ prescriptive models and asked to classify each based on the style of leading depicted. All individuals correctly classified the passages.

Leader Choice

After reading the three statements, individuals selected their preferred leader. Choice data were used to classify participants into personality and work values profiles.

Perceived Leader Similarity

Perceived similarity was measured using six items from Turban and Jones (1988) (e.g., “This leader and I would see things in much the same way.”) and Liden et al. (1993) (e.g., “This leader and I would handle problems in a similar way.”) (α = .93).

Results

We first assessed for any univariate and multivariate outliers by examining whether any cases possessed z-scores greater than ±3.00 on the study variables or met the p < .001 criterion for Mahalanobis distance, respectively (Fidell and Tabachnick 2003). Results did not reveal any outliers among the cases. When asked to make their leader selections, 191 (45.9%) participants chose the charismatic leader, 96 (23.0%) selected the ideological leader, and 128 (30.9%) opted for the pragmatic leader. A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) employing Fisher’s LSD post hoc analysis for group comparisons, with overall leader choice as the grouping variable and perceived similarity to the leader as the outcome variable, suggested respondents tended to choose the leader who they perceived to be most similar to themselves [charismatic: F(412) = 54.08, p < .01; ideological: F(412) = 16.32, p < .01; pragmatic: F(412) = 66.03, p < .01]. We conducted this analysis controlling for demographic characteristics of participants (age, gender, and work experience) and found no differences (see Table 2 for means and SDs). Thus, we report this analysis using the parsimonious model. Correlations among the personality and work values variables can be found in Table 3. Both sets of variables displayed low to moderate correlations among IVs, suggesting they are distinct enough to include in the discriminant function analyses.

Discriminant Function Analysis

To identify personality and work values profiles that would predict the probability of selecting a specific leader, consistent with similar studies (e.g., Ehrhart and Klein 2001), we used discriminant function analysis (DFA). DFA is used to classify cases when a dependent variable is categorical. We selected DFA over other analyses that may predict categorical outcomes (e.g., logistic regression) given we were interested in how personality and work values profiles, not single predictors, impact individuals’ leader choices. DFA assesses the relative importance of multiple independent variables (IVs) when distinguishing among groups on the dependent variable (DV), discarding IVs that have no impact on group distinctions (Tabachnick and Fidell 2001). DFA produces discriminant functions, which are latent variables consisting of linear combinations of discriminating IVs. The function loadings represent the discriminant coefficient for a given IV in the larger discriminant function. Thus, larger loadings reflect more discriminating variables (Tabachnick and Fidell 2001).

DFA produces one fewer discriminant function than the number of categories classified, where each function is orthogonal to the others. When multiple functions are created, the first maximizes differences between values on the DV, while the second maximizes values on the DV controlling for the first function. To analyze our data, two separate DFAs were conducted. One DFA using the personality variables as predictors yielded two discriminant functions. A second DFA using the work values variables as predictors also yielded two functions.Footnote 4 Before running each DFA, confirmatory factor analyses were conducted on the personality and work values variables, respectively, to evaluate their distinctiveness. For the personality variables, an 11-factor model was tested in which all items for the Big Five, authoritarianism, cognitive rigidity, rational mindedness, and the three temporal foci were specified to load onto their respective factors. This model displayed an adequate fit to the data: χ 2(2399) = 3016.20, p < .001; RMSEA = .03, comparative fit index (CFI) = .95, and incremental fit index (IFI) = .94, providing support for the 11-factor model. For the value variables, a 4-factor model was tested in which items for autonomy, teamwork, competition, and stability were specified to load onto their factors. This model also displayed an adequate fit: χ 2(117) = 191.50, p < .001; RMSEA = .04, CFI = .95, IFI = .95, thus lending support to the 4-factor model.

With respect to the DFAs, to avoid type I error, we used predicted group membership estimates unadjusted for prior knowledge of group sizes in the sample. This more conservative analysis reduces bias related to the assumption that the charismatic would be more likely to be selected in the population, as was found in this sample. Thus, it assumes that, without knowledge of the predictors, each leader is equally likely to be selected. We also utilized a stepwise entry method using Wilk’s lambda as the criteria of selection (i.e., the variable that minimizes Wilk’s lambda and maximizes Mahalanobis distance is selected). The resulting functions reflect linear combinations of variables that are most useful in distinguishing among participants who select a specific leader. Variables not meeting the criterion to enter were excluded from the analysis.

Additionally, to assess the potential influences of our control variables (gender, age, and work experience), we entered all IVs and control variables for the personality and values DFAs. Consistent with recommendations for using statistical controls in DFA (see Garson 2012), we compared the squared canonical correlations for two models, one with the control variables and one without. Results showed that the controls did not significantly explain differences in participants’ overall leader preference over and above the independent variables for each DFA. Thus, we did not include any control variables in the subsequent personality and values DFAs.

Personality

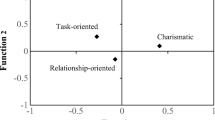

In contrasting the personality profiles that would predict the probability of selecting a particular leader, the first function provided a significant (r = .25, p < .01) canonical correlation. The upper portion of Table 4 lists the characteristics that distinguished the groups. This function, which we labeled “interpersonal-idealistic orientation,” consisted of higher levels of extraversion (r = .32), agreeableness (r = .34), and future focus (r = .36), and lower levels of rational mindedness (r = −.57), neuroticism (r = −.25), and past focus (r = −.59). An examination of the group mean centroids (Table 4), which reflect the distance between means for each group on the functions and thus inform interpretation of the factor loadings for each IV comprising the function, revealed that the function essentially distinguished between those preferring the charismatic leader (M = .32) and those preferring the pragmatic leader (M = −.38), with those preferring the ideological leader scoring near zero on the function (M = .06). Thus, individuals who preferred the charismatic leader scored highest on this function, or were more focused on interpersonal concerns and less on pragmatism, while those preferring the pragmatic leader scored lowest, or were less focused on interpersonal concerns and more on pragmatic thinking. In contrast to the first function, the second was not significant (r = .19, p = .06). The personality function was able to correctly classify 42.8% of participants’ leader preferences, which was significantly greater than the likelihood of proper classification due to chance alone (33.30%).Footnote 5

Work Values

The second DFA assessing work values resulted in two functions (Table 5). The first, which we labeled “individualism,” distinguished between individuals who selected the charismatic leader and those who chose the pragmatic leader and, to a lesser degree, the ideological leader (r = .22, p < .01). This function was defined by stronger values for competition (r = .73) and autonomy (r = .50) and a weaker value for teamwork (r = −.42). The group centroids revealed that the function differentiated among those who selected the charismatic leader (M = −.24) and those who chose the pragmatic (M = .27) and, to a lesser degree, the ideological leader (M = .12). Participants who preferred the charismatic leader scored lowest on this function, or were more focused on collective concerns, while those preferring the pragmatic leader were more focused on individual concerns. Those preferring the ideological leader largely scored in the middle on this function. In contrast to the first function, the second was not significant (r = .15, p = .06). The work values functions correctly classified 49.8% of participants’ overall leader choices, compared to the likelihood of proper classification as a result of chance alone (33.30%).

Overall, our findings suggest that those who preferred the charismatic leader tended to be more socially and collectively oriented, future focused, and less rational minded. Specifically, in terms of personality, they tended to be more extraverted, agreeable, and future focused and less neurotic, rational minded, and past focused. In terms of work values, they tended to hold weaker values for competition and autonomy and a higher value for teamwork. In contrast, those preferring the pragmatic leader tended to be less socially and collectively oriented, more rational minded, and more likely to value autonomy and competition. Specifically, in terms of personality traits, they tended to be less extraverted, agreeable, and future focused and more neurotic, rational minded, and past focused. In terms of work values, they tended to possess stronger values for competition and autonomy and a weaker value for teamwork. Finally, those who preferred the ideological leader tended to score in the middle on the personality function (interpersonal-idealistic orientation) and the work values function (individualistic orientation).

Post hoc Qualitative Analyses

To gain additional insight into our quantitative findings, we asked participants to (a) list as many adjectives as they could to describe each leader and to (b) explain why they chose the leader that they did. For the adjectival descriptions of each leader, we grouped responses based on participants’ leader choices. This allowed us to compare the reactions that participants with different style preferences had for the same leader. In so doing, we sought to examine the range of responses, both favorable and unfavorable, that participants had for each type of leader, thus adding insight into how charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic leaders are uniquely perceived by different people. Further, participants’ leader choice rationales provided a richer explanation for their preferences, allowing us to delve deeper into why they selected the leader that they did. These analyses also supported the notion that participants were not merely restating what they had read about the leaders in the vignettes but, rather, that they were forming unique and meaningful opinions about each of the leaders, which informed their personal preferences. Sample adjectives and choice rationales can be found in Appendices B and C, respectively.

Adjectival Descriptions

Participants preferring the charismatic leader listed adjectives that centered on charisma, unity, supportiveness, participation, innovation, and the future. Yet, those who chose the ideological and pragmatic leaders were more suspicious, listing adjectives that included insincere, egoistic, arrogant, grandiose, proselytizing, and use of flowery speech.

Those selecting the ideological leader listed adjectives centering on sincerity, strength, decisiveness, conservatism, traditional values, and respect for the past. Yet, those preferring the charismatic and pragmatic leaders tended to describe the ideologue as negative, intolerant, rigid, domineering, insensitive, polarizing, and too focused on the past. Finally, those preferring the pragmatic leader described this leader as rational, fact-driven, problem-focused, planful, and resourceful. Yet, those preferring the other two leaders described the pragmatic as dry and emotionless, uninspiring, arrogant, and overly focused on business, rather than social, issues.

Choice Rationales

Finally, we explored the reasons participants gave for their selections (see Appendix C). Coinciding with the adjectival descriptions, those selecting the charismatic leader stressed their relational way of leading, including their inspiring rhetoric, positivity, and concern for followers. They placed more value on teamwork and the leader’s unifying vision, as well as their openness to ideas, risk-taking, and future focus. Yet, many believed the ideologue was too negative, dogmatic, and past focused. A theme among those preferring the charismatic was on moving beyond the past in a positive way. The following quotes underscore this theme:

Leader I was negative and focused on the past. Leader C is focused on the future, energetic, confident about the challenges, and will be able to inspire others.

This leader speaks of a common vision for all employees … [and] seems to have the energy and the dynamic attitude to erase the shadow that was cast on the agency.

Leader C had the right balance of authority and direction. Leader I was too aggressive and knocked folks over the head with their version of the truth.

Participants who preferred the charismatic leader also tended to perceive the pragmatic leader as dry, overly analytical, and incapable of inspiring positive change. One individual noted:

Leader P … is too analytical and focused on the numbers to really inspire employees, clients, or donors to embrace changes and reenergize the organization.

In contrast, those selecting the ideological leader stressed the leader’s candor, focus on returning to the values of Big Buddies, and willingness to address the scandal. What was critical was not inspirational oratory or a focus on change. Rather, these individuals appreciated candid rhetoric that focused on going back to Big Buddies’ roots. Several quotes highlight this theme.

He did not make it seem he would come in and change the organization but push to bring it back to its values .,.. He seemed to be genuine and not to push new ideas on everyone. Leader I … was a “straight talker.” Leaders C and P only provided colorful speeches … I also like how he did not shy away from misgivings of the previous management and placed a focus on traditional values.

Participants who chose the ideological leader also believed the pragmatic leader was too analytical. Yet, they focused more on the pragmatic’s lack of focus on values, in contrast to more relational issues cited by those preferring the charismatic. For example, two participants noted:

Leader P wanted to … bring in analytics to solve the problems. When working with the public, things don’t work that way. It’s important the company get back to its roots ...

Leader P was focused solely on the numbers, not the values of the organization.

Finally, those selecting the pragmatic leader placed a heavier focus on logical problem-solving, detailed strategies, and fact-based solutions. They were not drawn to emotional oratory, but rather desired a realistic leader who could articulate concrete plans for solving problems:

I prefer a more realistic approach to the flowery, ‘isn’t life wonderful’ approach … realistic leaders who know how to lead is what it takes to make a successful business ... I am analytic like Leader P. I want to be more specific in my analysis and plans ...

Discussion

Recently, questions have arisen over whether charismatic and transformational leader behaviors are universally effective and, if not, what other forms of leading might be explored more fully (e.g., Li et al. 2013; Parr et al. 2013; Hunter et al. 2009, 2011; Mumford 2006). Importantly, answers to these questions are not found by focusing solely on leaders and their behaviors. Rather, it is critical to determine how different followers respond to such behaviors.

Merging this understanding that influence is a function of followers’ interpretations of leader behaviors with the growing questions over charismatic and transformational behaviors’ universal appeal, this study sought to examine how followers’ personal profiles may influence their reactions to charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic styles of leading, namely during crises. Addressing calls for more attention to followers (e.g., Uhl-Bien et al. 2014) and building on a growing body of research on follower typologies (e.g. Carsten et al. 2010; Thoroughgood et al. 2012), our results tentatively suggest that certain types of people may prefer charisma, while other types of people may prefer rational, problem-focused or traditional, values-based styles of leading. By taking a broader, profile approach and exploring the range of responses that different people may have to three previously established forms of leader behavior, we expand on prior studies that have focused narrowly on specific personal characteristics related to perceptions of charismatic and transformational behavior (e.g., Felfe and Schyns 2006, 2010; Schyns and Sanders 2007) and people’s implicit beliefs about charisma as an ideal leader trait (e.g., Keller 1999).

Consistent with and expanding on prior research, individuals who are more people- and team-oriented, emotionally stable, future focused, and less rationally minded tended to prefer the charismatic leader. Yet, a majority of the sample (∼54%) did not prefer the charismatic. For these participants, results tentatively suggested that an emphasis on rational problem-solving or traditional values was more important. In contrast to those who preferred the charismatic leader, individuals preferring the pragmatic leader tended to be less extraverted, agreeable, and team-oriented and more focused on rationality, autonomy, and competition. Interpreted within the context of our personality and work values functions, people who preferred the charismatic leader exhibited a more interpersonal, idealistic, and collectivistic orientation, while individuals who preferred the pragmatic leader demonstrated a more socially detached, pragmatic, and individualistic orientation. Interestingly, individuals preferring the ideological leader tended to score in between the other two preferences groups with respect to these broad orientations.

Theoretical Implications

This study has several theoretical implications. First, our findings highlight the need for more contextualized views on outstanding leader behavior. The literature’s leader-centric focus has led to an assumption that charismatic and transformational behaviors hold universal appeal. Given leadership is a social process embedded in context, it requires more holistic investigations that account for other pieces of the leadership puzzle. This study takes another step toward this goal by examining the alignment between different leader styles and different types of followers.

Second, although followers are often treated as an “under-explored source of variance in understanding leadership processes” (Lord et al. 1999, p. 167), our results suggest distinctions between those preferring different styles of leading. Turning to the future, we see promise in expanding the current investigation to include additional characteristics. For example, leader preferences may vary based on followers’ self-construals. Those preferring a charismatic leader may define themselves in more collectivistic terms (Howell and Shamir 2005), while individuals who tend to prefer pragmatic leaders may define themselves in a more individualistic fashion.

Third, our findings suggest the need for further mapping of follower profiles onto other models of leader behavior. For example, what types of followers value the fatherly benevolence, yet strong discipline, of a paternalistic leader or the service orientation of a servant leader? An understanding of what follower types are compatible with different styles of leading is needed to build more holistic theoretical models that explain both sides of the leader-follower equation.

Practical Implications

From a practical standpoint, our results highlight the often overlooked fact that influence depends on its target (French and Raven 1959). Part of cultivating leaders involves matching the right leaders with the right situations that fit their styles (Fiedler 1971). Our results point to the potential advantages of organizations placing a greater focus on matching supervisors and subordinates based on personality and work values profiles. To foster such efforts, employers might benefit from selection and placement initiatives that focus equally on understanding subordinate characteristics and how leaders may or may not “fit” with certain subordinates as they do on traits of leaders. Of course, such initiatives should be tempered by an understanding that too much similarity between supervisors and subordinates may stifle constructive dissent or creative problem-solving. Yet, taking a one-sided view on promoting leader effectiveness by focusing only leaders misses the role of follower characteristics in shaping influence processes.

Limitations

This study is not without its limitations. First, while the use of “paper leader” scenarios is not uncommon in leadership research, some suggest they fall short of producing the effects observed in an actual organization (Landy 2008). Yet, the use of written speeches aligned with our goal of comparing follower characteristics that, together, predict preferences for different styles of leading. Written speeches also allowed us to control for potential confounds associated with video and simulation methods, such as leaders’ appearance and tone of voice. Second, while extensive efforts were made to ensure the three speeches reflected the theoretical underpinnings of the CIP model, these leader styles were treated in independent terms. However, as mentioned earlier, certain leaders may display elements of each. Examining perceptions of “mixed-typed” styles of leading may explain the influence of leaders who do not fit neatly into a given category.

Third, it might be argued that our findings are unique to crisis situations. However, in creating the study’s fictional scenario, we adhered to a core tenet of CIP theory that differences between charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic styles of leading are best observed during times of crisis (Mumford 2006). This allowed us to more fully contrast these different styles and, in so doing, more effectively examine potential differences in the types of individuals who prefer them. Even so, future studies should seek to replicate our findings in more mundane settings. Finally, we cannot rule out potential situational effects stemming from the study’s non-profit scenario. As such, future studies should seek to replicate our findings in different contexts and examine how follower profiles may interact with situational factors to shape leader preferences.

Notes

Importantly, these differences are malleable—a point made by Weber (1924) and more recently Hunter et al. (2011). For example, charismatic leaders can behave pragmatically when solving problems, while ideological leaders may draw on themes of hope and optimism when articulating their values. The CIP model does not suggest leaders fit neatly into three categories. Rather, it suggests that reliable differences across these styles that can be meaningfully studied.

Although a political setting would have also been a suitable context for the present study, the general feedback from our ten CIP experts was that the unique dynamics of a political organization might limit the generalizability of our findings. In contrast, a nonprofit allowed us to depict a more traditional work setting found in many for profit organizations, while also describing an organization with a strong values-based mission that is at the core of ideological leaders’ prescriptive mental models.

Research suggests that individuals’ values, or their beliefs about desirable end states or behaviors that transcend situations and vary in content and intensity (Rokeach 1973; Schwartz 1992; Schwartz and Bilsky 1987, 1990), share systematic relations with their personality traits (see Bilsky and Schwartz 1994). In explanation, Bilsky and Schwartz (1994) argued that people’s personalities and values, although distinct, share similar underlying motivational dynamics such that they likely reciprocally affect one another. That is, our personalities shape and reinforce our values, which, in turn, promote congruent behavioral patterns consistent with our personalities, and so on. Thus, given personality and values are distinct, yet overlapping in nature (i.e., sharing common variance), we generated separate discriminant functions for participants’ personality and work values for the sake of parsimony and conceptual clarity. That is, we felt that separate DFAs for personality and work values would provide cleaner, more interpretable solutions given the variables comprising the functions are more conceptually distinct, respectively.

Case-wise classifications were also examined to determine whether any patterns emerged in misclassified participants based on the personality and work values functions (i.e., whether individuals who were predicted to choose one type of leader often chose a different leader). However, no patterns emerged based on our analysis.

References

Altemeyer, B. (1981). Right-wing authoritarianism. University of Manitoba press.

Altemeyer, B. (1988). Enemies of freedom: understanding right-wing authoritarianism. Jossey-Bass.

Barbuto, J. E. (2000). Influence triggers: a framework for understanding follower compliance. The Leadership Quarterly, 11, 365–387. doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(00)000045-X.

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership: good, better, best. Organizational Dynamics, 13, 26–40. doi:10.1016/0090-2616(85)90028-2.

Bedell, K., Hunter, S., Angie, A., & Vert, A. (2006). A historiometric examination of Machiavellianism and a new taxonomy of leadership. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 12, 50–72. doi:10.1177/107179190601200404.

Bedell-Avers, K. E., Hunter, S. T., Angie, A. D., Eubanks, D. L., & Mumford, M. D. (2009). Charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic leaders: an examination of leader-leader interactions. The Leadership Quarterly, 20, 299–315. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.03.014.

Bedell-Avers, K. E., Hunter, S. T., & Mumford, M. D. (2008). Conditions of problem-solving and the performance of charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic leaders: a comparative experimental study. The Leadership Quarterly, 19, 89–106. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.12.006.

Berings, D., De Fruyt, F., & Bouwen, R. (2004). Work values and personality traits as predictors of enterprising and social vocational interests. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 349–364. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00101-6.

Bilsky, W., & Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Values and personality. European Journal of Personality, 8, 163–181. doi:10.1002/per.2410080303.

Brislin, R. W., & Kim, E. S. (2003). Cultural diversity in people’s understanding and uses of time. Applied Psychology, 52, 363–382. doi:10.1111/1464-0597.00140.

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper & Row.

Byrne, D. E. (1971). The attraction paradigm. Academic Press.

Carsten, M. K., Uhl-Bien, M., West, B. J., Patera, J. L., & McGregor, R. (2010). Exploring social constructions of followership: a qualitative study. The Leadership Quarterly, 21, 543–562. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.03.015.

Conger, J. A., & Kanungo, R. N. (1987). Toward a behavioral theory of charismatic leadership in organizational settings. Academy of Management Review, 12, 637–647. doi:10.5465/AMR.1987.4306715.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 4(1), 5–13.

Cronbach, L. (1955). Processes affecting scores on “understanding of others” and “assumed similarity.”. Psychological Bulletin, 52, 177–193. doi:10.1037/h0044919.

Das, T. K. (1987). Strategic planning and individual temporal orientation. Strategic Management Journal, 8, 203–209. doi:10.1002/smj.4250080211.

Denson, T. F., Pedersen, W. C., & Miller, N. (2006). The displaced aggression questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 1032–1051. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.90.6.1032.

Ehrhart, M. G., & Klein, K. J. (2001). Predicting followers’ preferences for charismatic leadership: the influence of follower values and personality. The Leadership Quarterly, 12, 153–179. doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(01)00074-1.

Engle, E. M., & Lord, R. G. (1997). Implicit theories, self-schemas, and leader-member exchange. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 988–1010. doi:10.2307/256956.

Epitropaki, O., & Martin, R. (2004). Implicit leadership theories in applied settings: factor structure, generalizability, and stability over time. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 293–310. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.2.293.

Epley, N., Keysar, B., Van Boven, L., & Gilovich, T. (2004). Perspective taking as egocentric anchoring and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 327–339. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.327.

Epstein, S. (1994). An integration of the cognitive and psychodynamic unconscious. American Psychologist, 49, 709–724. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.49.8.709.

Felfe, J., & Schyns, B. (2006). Personality and the perception of transformational leadership: the impact of extraversion, neuroticism, personal need for structure, and occupational self-efficacy. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36, 708–739. doi:10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00026.x.

Felfe, J., & Schyns, B. (2010). Followers’ personality and the perception of transformational leadership: further evidence for the similarity hypothesis. British Journal of Management, 21, 393–410. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8551.2009.00649.x.

Fidell, L. S., & Tabachnick, B. G. (2003). Preparatory data analysis. In J. A. Schinka & W. F. Velicer (Eds.), Handbook of psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 115–121). New York: Wiley.

Fiedler, F. E. (1971). Validation and extension of the contingency model of leadership effectiveness: a review of empirical findings. Psychological Bulletin, 76, 128–148. doi:10.1037/h0031454.

French Jr., J. R. P., & Raven, B. H. (1959). The bases of social power. In D. Cartwright (Ed.), Studies in social power (pp. 150–167). Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research.

Fried, Y., & Slowik, L. H. (2004). Enriching goal-setting theory with time: an integrated approach. Academy of Management Review, 29, 404–422. doi:10.2307/20159051.

Garson, G. D. (2012). Discriminant function analysis. Asheboro, NC: Statistical Associates Publishers. doi:10.2307/20159051.

Graziano, W. G., Jensen-Campbell, L. A., & Hair, E. C. (1996). Perceiving interpersonal conflict and reacting to it: the case for agreeableness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 820–835. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.4.820.

Hollander, E. P. (1993). Legitimacy, power and influence: a perspective on relational features of leadership. In M. M. Chemers & R. Ayman (Eds.), Leadership theory and research: perspectives and directions (pp. 29–48). San Diego: Academic Press.

House, R. J. (1971). A path goal theory of leader effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 16, 321–339. doi:10.2307/2391905.

House, R. J. (1977). A 1976 theory of charismatic leadership. In J. G. Hunt & L. L. Larson (Eds.), Leadership: the cutting edge (pp. 189–207). Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

House, R. J., & Howell, J. M. (1992). Personality and charismatic leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 3, 81–108. doi:10.1016/1048-9843(92)90028-E.

Howell, J. M., & Shamir, B. (2005). The role of followers in the charismatic leadership process: relationships and their consequences. Academy of Management Review, 30, 96–112. doi:10.5465/AMR.2005.15281435.

Hunter, S. T., Bedell-Avers, K. E., & Mumford, M. D. (2009). Impact of situational framing and complexity on charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic leaders: investigation using a computer simulation. The Leadership Quarterly, 20, 383–404. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.03.007.

Hunter, S. T., Cushenbery, L., Thoroughgood, C., Johnson, J. E., & Ligon, G. S. (2011). First and ten leadership: a historiometric investigation of the CIP leadership model. The Leadership Quarterly, 22, 70–91. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.12.008.

Ji, L. J., Guo, T., Zhang, Z., & Messervey, D. (2009). Looking into the past: cultural differences in perception and representation of past information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96, 761–769. doi:10.1037/a0014498.

John, O. P., Donahue, E. M., & Kentle, R. L. (1991). The big five inventory—versions 4a and 54. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research.

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., & Sulloway, F. J. (2003). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 339–375. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.339.

Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2000). Five-factor model of personality and transformational leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 751–765. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.85.5.751.

Judge, T. A., Erez, A., Bono, J. E., & Thoresen, C. J. (2003). The core self-evaluations scale: development of a measure. Personnel Psychology, 56, 303–331. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00152.x.

Judge, T. A., & Piccolo, R. F. (2004). Transformational and transactional leadership: a meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 755–768. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.755.

Jung, D. I., & Avolio, B. J. (1999). Effects of leadership style and followers’ cultural orientation on performance in group and individual task conditions. Academy of Management Journal, 42, 208–218. doi:10.2307/257093.

Keller, T. (1999). Images of the familiar: individual differences and implicit leadership theories. The Leadership Quarterly, 10, 589–607. doi:10.2307/257093.

Kerr, S., & Jermier, J. M. (1978). Substitutes for leadership: their meaning and measurement. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 22, 375–403. doi:10.1016/0030-5073(78)90023-5.

Klein, K. J., & House, R. J. (1995). On fire: charismatic leadership and levels of analysis. The Leadership Quarterly, 6, 183–198. doi:10.1016/1048-9843(95)90034-9.

Kuppens, P., & Van Mechelen, I. (2007). Interactional appraisal models for the anger appraisals of threatened self-esteem, other-blame, and frustration. Cognition and Emotion, 21, 56–77. doi:10.1080/02699930600562193.

Landy, F. J. (2008). Stereotypes, bias, and personnel decisions: strange and stranger. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 1, 379–392. doi:10.1111/j.1754-9434.2008.00071.x.

Larsen, R. J., & Ketelaar, T. (1991). Personality and susceptibility to positive and negative emotional states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 132–140. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.132.

Li, N., Chiaburu, D. S., Kirkman, B. L., & Xie, Z. (2013). Spotlight on the followers: an examination of moderators of relationships between transformational leadership and subordinates’ citizenship and taking charge. Personnel Psychology, 66, 225–260. doi:10.1111/peps.12014.

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., & Stilwell, D. (1993). A longitudinal study on the early development of leader-member exchanges. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 662–674. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.662.

Ligon, G. S., Hunter, S. T., & Mumford, M. D. (2008). Development of outstanding leadership: a life narrative approach. The Leadership Quarterly, 19, 312–334. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.03.005.

Lord, R. G., Brown, D. J., & Freiberg, S. J. (1999). Understanding the dynamics of leadership: the role of follower self-concepts in the leader/follower relationship. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 78, 167–203. doi:10.1006/obhd.1999.2832.

Lord, R. G., Foti, R. J., & De Vader, C. L. (1984). A test of leadership categorization theory: internal structure, information processing, and leadership perceptions. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 34, 343–378. doi:10.1016/0030-5073(84)90043-6.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1986). Personality, coping, and coping effectiveness in an adult sample. Journal of Personality, 54, 385–404. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1986.tb00401.x.

Morelli, G., & Andrews, L. (1980). Rationality and its relation to extraversion and neuroticism. Psychological Reports, 47, 1111–1114. doi:10.2466/pr0.1980.47.3f.1111.

Mumford, M. D. (2006). Pathways to outstanding leadership: a comparative analysis of charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic leaders. Psychology Press.

Mumford, M. D., Antes, A. L., Caughron, J. J., & Friedrich, T. L. (2008). Charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic leadership: multi-level influences on emergence and performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 19, 144–160. doi:10.2466/pr0.1980.47.3f.1111.

Oreg, S. (2003). Resistance to change: developing an individual differences measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 680–693. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.4.680.

Pacini, R., & Epstein, S. (1999). The relation of rational and experiential information processing styles to personality, basic beliefs, and the ratio-bias phenomenon. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 972–987. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.76.6.972.

Padilla, A., Hogan, R., & Kaiser, R. B. (2007). The toxic triangle: destructive leaders, susceptible followers, and conducive environments. The Leadership Quarterly, 18, 176–194. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.03.001.

Parr, A. D., Hunter, S. T., & Ligon, G. S. (2013). Questioning universal applicability of transformational leadership: examining employees with autism spectrum disorder. The Leadership Quarterly, 24, 608–622. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.04.003.

Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. New York: Free Press.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 1–65). Orlando, FL: Academic. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60281-6.

Schwartz, S. H., & Bilsky, W. (1987). Toward a psychological structure of human values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 550–562. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.53.3.550.

Schwartz, S. H., & Bilsky, W. (1990). Toward a theory of the universal content and structure of values: extensions and cross-cultural replications. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 878–891. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.5.878.

Schyns, B., & Felfe, J. (2006). The personality of followers and its effects on the perception of leadership: an overview, a study, and a research agenda. Small Group Research, 37, 522–539. doi:10.1177/1046496406293013.

Schyns, B., & Sanders, K. (2007). In the eyes of the beholder: personality and the perception of leadership. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 37, 2345–2363. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2007.00261.x.

Shamir, B., & Howell, J. M. (1999). Organizational and contextual influences on the emergence and effectiveness of charismatic leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 10, 257–283. doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(99)00014-4.

Shamir, B., House, R. J., & Arthur, M. B. (1993). The motivational effects of charismatic leadership: a self-concept based theory. Organization Science, 4, 577–594. doi:10.1287/orsc.4.4.577.

Shipp, A. J., Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2009). Conceptualization and measurement of temporal focus: the subjective experience of the past, present, and future. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 110, 1–22. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.05.001.

Strange, J. M., & Mumford, M. D. (2002). The origins of vision: charismatic versus ideological leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 13, 343–377. doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00125-X.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics. New York: Harper & Row.