Abstract

In recent years there has been a growing interest in problems, where either the observed data or hidden state variables are confined to a known Riemannian manifold. In sequential data analysis this interest has also been growing, but rather crude algorithms have been applied: either Monte Carlo filters or brute-force discretisations. These approaches scale poorly and clearly show a missing gap: no generic analogues to Kalman filters are currently available in non-Euclidean domains. In this paper, we remedy this issue by first generalising the unscented transform and then the unscented Kalman filter to Riemannian manifolds. As the Kalman filter can be viewed as an optimisation algorithm akin to the Gauss-Newton method, our algorithm also provides a general-purpose optimisation framework on manifolds. We illustrate the suggested method on synthetic data to study robustness and convergence, on a region tracking problem using covariance features, an articulated tracking problem, a mean value optimisation and a pose optimisation problem.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the rare cases when \(h: T\mathcal{M} \rightarrow\mathcal{M}_{\mathrm {obs}}\), we can consider \(\hat{h} (\cdot) \equiv h (\operatorname{Exp}(\cdot))\) instead.

These results are attained using a single-thread C++ implementation on a 1.6 GHz Intel Xeon.

We also experimented with slowly decreasing the size of this covariance, akin to weight decay, but did not observe any noticeable difference for this problem.

References

Balan, A.O., Sigal, L., Black, M.J.: A quantitative evaluation of video-based 3D person tracking. In: 2nd Joint IEEE International Workshop on Visual Surveillance and Performance Evaluation of Tracking and Surveillance, pp. 349–356 (2005)

Bandouch, J., Engstler, F., Beetz, M.: Accurate human motion capture using an ergonomics-based anthropometric human model. In: AMDO’08: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Articulated Motion and Deformable Objects. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 5098, pp. 248–258. Springer, Berlin (2008)

Bell, B.M., Cathey, F.W.: The iterated Kalman filter update as a Gauss-Newton method. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 38, 294–297 (1993)

Cappé, O., Godsill, S.J., Moulines, E.: An overview of existing methods and recent advances in sequential Monte Carlo. Proc. IEEE 95(5), 899–924 (2007)

do Carmo, M.P.: Riemannian Geometry. Birkhäuser, Boston (1992)

Caselles, V., Kimmel, R., Sapiro, G.: Geodesic active contours. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 22, 61–79 (1997)

Engell-Nørregård, M., Erleben, K.: A projected back-tracking line-search for constrained interactive inverse kinematics. Comput. Graph. 35(2), 288–298 (2011)

Erleben, K., Sporring, J., Henriksen, K., Dohlmann, H.: Physics Based Animation. Charles River Media, Newton Center (2005)

Fletcher, P.T., Joshi, S.: Riemannian geometry for the statistical analysis of diffusion tensor data. Signal Process. 87, 250–262 (2007)

Fletcher, P.T., Lu, C., Pizer, S.M., Joshi, S.: Principal geodesic analysis for the study of nonlinear statistics of shape. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 23(8), 995–1005 (2004)

Hairer, E., Lubich, C., Wanner, G.: Geometric Numerical Integration: Structure Preserving Algorithms for Ordinary Differential Equations. Springer, Berlin (2004)

Hauberg, S., Pedersen, K.S.: Stick it! Articulated tracking using spatial rigid object priors. In: Asian Conference on Computer Vision. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 6494. Springer, Berlin (2010)

Hauberg, S., Pedersen, K.S.: Predicting articulated human motion from spatial processes. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 94, 317–334 (2011)

Hauberg, S., Pedersen, K.S.: HUMIM software for articulated tracking. Tech. Rep. 01/2012, Department of Computer Science, University of Copenhagen (2012)

Hauberg, S., Sommer, S., Pedersen, K.S.: Gaussian-like spatial priors for articulated tracking. In: ECCV. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 6311, pp. 425–437. Springer, Berlin (2010)

Hauberg, S., Sommer, S., Pedersen, K.S.: Natural metrics and least-committed priors for articulated tracking. Image Vis. Comput. 30(6–7), 453–461 (2012)

Julier, S.J., Uhlmann, J.K.: A new extension of the Kalman filter to nonlinear systems. In: International Symposium Aerospace/Defense Sensing, Simulation and Controls, pp. 182–193 (1997)

Kalman, R.: A new approach to linear filtering and prediction problems. J. Basic Eng. 82(D), 35–45 (1960)

Karcher, H.: Riemannian center of mass and mollifier smoothing. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 30(5), 509–541 (1977)

Kendall, D.G.: Shape manifolds, procrustean metrics, and complex projective spaces. Bull. Lond. Math. Soc. 16(2), 81–121 (1984)

Kjellström, H., Kragić, D., Black, M.J.: Tracking people interacting with objects. In: IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 747–754 (2010)

Kraft, E.: A quaternion-based unscented Kalman filter for orientation tracking. In: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Information Fusion, pp. 47–54 (2003)

Kwon, J., Lee, K.M.: Monocular SLAM with locally planar landmarks via geometric rao-blackwellized particle filtering on Lie groups. In: IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 1522–1529 (2010)

Kwon, J., Lee, K.M., Park, F.C.: Visual tracking via geometric particle filtering on the affine group with optimal importance functions. In: Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 991–998 (2009)

Lewis, F.L.: Optimal Estimation: With an Introduction to Stochastic Control Theory. Wiley, New York (1986)

Li, R., Chellappa, R.: Aligning spatio-temporal signals on a special manifold. In: ECCV. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 6315, pp. 547–560. Springer, Berlin (2010)

Liu, X., Srivastava, A., Gallivan, K.: Optimal linear representations of images for object recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 26(5), 662–666 (2004)

van der Merwe, R., Doucet, A., Freitas, N.D., Wan, E.: The unscented particle filter. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2000), vol. 13, pp. 584–590. MIT Press, Cambridge (2001)

Misner, C., Thorne, K., Wheeler, J.: Gravitation. W.H. Freeman, New York (1973)

Pennec, X.: Intrinsic statistics on Riemannian manifolds: basic tools for geometric measurements. J. Math. Imaging Vis. 25(1), 127–154 (2006)

Pennec, X., Fillard, P., Ayache, N.: A Riemannian framework for tensor computing. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 66, 41–66 (2004)

Poppe, R.: Vision-based human motion analysis: an overview. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 108(1–2), 4–18 (2007)

Porikli, F., Tuzel, O., Meer, P.: Covariance tracking using model update based on Lie algebra. In: Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, vol. 1, pp. 728–735 (2006)

Rabiner, L.R.: A tutorial on hidden Markov models and selected applications in speech recognition. Proc. IEEE 77(2), 257–286 (1989)

Sidenbladh, H., Black, M.J., Fleet, D.J.: Stochastic tracking of 3D human figures using 2D image motion. In: ECCV, vol. II. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 1843, pp. 702–718. Springer, Berlin (2000)

Sigal, L., Black, M.J.: HumanEva: synchronized video and motion capture dataset for evaluation of articulated human motion. Tech. Rep. CS-06-08, Brown University (2007)

Singhal, S., Wu, L.: Training multilayer perceptrons with the extended Kalman algorithm. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 1, pp. 133–140 (1989)

Sipos, B.J.: Application of the Manifold-Constrained unscented Kalman filter. In: Position, Location and Navigation Symposium, IEEE/ION, pp. 30–43 (2008)

Sommer, S., Tatu, A., Chen, C., Jørgensen, D.R., de Bruijne, M., Loog, M., Nielsen, M., Lauze, F.: Bicycle chain shape models. In: IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, pp. 157–163. IEEE Computer Society, Los Alamitos (2009)

Sommer, S., Lauze, F., Nielsen, M.: The differential of the exponential map, Jacobi fields and exact principal geodesic analysis. CoRR (2010). arXiv:1008.1902

Srivastava, A., Klassen, E.: Bayesian and geometric subspace tracking. Adv. Appl. Probab. 36(1), 43–56 (2004)

Subbarao, R., Meer, P.: Nonlinear mean shift over Riemannian manifolds. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 84(1), 1–20 (2009)

Tidefelt, H., Schön, T.B.: Robust point-mass filters on manifolds. In: Proceedings of the 15th IFAC Symposium on System Identification (SYSID), pp. 540–545 (2009)

Tuzel, O., Porikli, F., Meer, P.: Region covariance: A fast descriptor for detection and classification. In: Leonardis, A., Bischof, H., Pinz, A. (eds.) ECCV. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 3952, pp. 589–600. Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg (2006)

Tyagi, A., Davis, J.W.: A recursive filter for linear systems on Riemannian manifolds. In: Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 1–8 (2008)

Wan, E.A., van der Merwe, R.: The unscented Kalman filter for nonlinear estimation. In: Adaptive Systems for Signal Processing, Communications, and Control Symposium, IEEE, pp. 153–158 (2002)

Ward, R.C.: Numerical computation of the matrix exponential with accuracy estimate. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 14, 600–610 (1977)

Wu, Y., Wu, B., Liu, J., Lu, H.: Probabilistic tracking on Riemannian manifolds. In: International Conference on Pattern Recognition, pp. 1–4 (2008)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for detailed comments, which substantially improved the quality of the manuscript. Furthermore, Søren Hauberg would like to thank the Villum Foundation for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below are the links to the electronic supplementary material.

(MP4 1.4 MB)

(MP4 4.6 MB)

(MP4 4.7 MB)

(MP4 899 kB)

(MP4 15.0 MB)

(MP4 4.8 MB)

(MP4 4.7 MB)

Appendices

Appendix A: Definitions from Differential Geometry

We give definitions of some concepts from differential geometry that we use in the paper (mainly from [5]) for the convenience of the reader.

-

1.

Differentiable Manifolds: A differentiable manifold of dimension M is a set \(\mathcal{M}\) and a family of injective mappings \(\mathcal{T}\) = \(\{x_{i}: U_{i} \subset\mathbb {R}^{M} \to\mathcal{M}\}\) of open sets U i of ℝM into \(\mathcal{M}\) such that

-

\(\bigcup_{i} x_{i}(U_{i}) = \mathcal{M}\), i.e. the open sets cover \(\mathcal{M}\).

-

For any pair i,j with x i (U i )⋂x j (U j )=W≠ϕ, the mapping \(x_{j}^{-1} \circ x_{i}\) is differentiable.

-

The family \(\mathcal{T}\) is maximal, which means that if (y,V), \(y:V\subset \mathbb{R}^{M}\to\mathcal{M}\) is such that: for each element of \(\mathcal{T}\), (x i ,U i ) with \(x_{i}(U_{i})\cap y(V)\not= 0\) implies that y −1∘x i is a diffeomorphism, then in fact \((y,V)\in\mathcal{T}\).

-

-

2.

Directional derivative of a function along a vector field: A vector field X on \(\mathcal{M}\) is a map that associates to each \(p\in\mathcal{M}\) an element \(X(p)\in T_{p}\mathcal{M}\), where \(T_{p}\mathcal{M}\) is the tangent space of \(\mathcal{M}\) at p. The space of smooth vector fields on \(\mathcal{M}\) is denoted \({\frak{X}}(\mathcal{M})\). Let \(f:\mathcal{M}\to\mathbb{R}\) be a differentiable function of \(\mathcal{M}\) and X a vector field on \(\mathcal{M}\). The directional derivative X.f is the function \(\mathcal{M}\to\mathbb{R}\),

(53)

(53)the differential of f at p evaluated at vector X(p).

-

3.

Covariant tensors: A p-covariant tensor h is a \(\mathcal{C}^{\infty}\) p-linear map

(54)

(54)i.e., for all \(x\in\mathcal{M}\), x↦h x :

(55)

(55)is p-linear and for vector fields \(X_{1},\dots,X_{p} \in{\frak{X}}\), the map x↦h x (X 1(x),…,X p (x)) is smooth.

-

4.

Riemannian Metric: A Riemannian metric on a manifold \(\mathcal{M}\) is a covariant 2-tensor g which associates to each point \(p\in\mathcal{M}\) an inner product g p =〈−,−〉 p on the tangent space \(T_{p}\mathcal{M}\), i.e., not only is it bilinear, but symmetric and positive definite and thus define a Euclidean distance on each tangent space. In terms of local coordinates, the metric at each point x is given by a matrix, g ij =〈X i ,X j 〉 x , where X i ,X j are tangent vectors to \(\mathcal{M}\) at x, and it varies smoothly with x. A Geodesic curve is a local minimiser of arc-length computed with a Riemannian metric.

-

5.

Affine connection: An affine connection ∇ on a differentiable manifold \(\mathcal {M}\) is a mapping

(56)

(56)which is denoted by ∇(X,Y)→∇ X Y and which satisfies the following properties:

-

∇ fX+gY Z=f∇ X Z+g∇ Y Z

-

∇ X (Y+Z)=∇ X Y+∇ X Z

-

∇ X (fY)=f∇ X Y+X(f)Y

in which \(X,Y,Z \in{\frak{X}}(\mathcal{M})\) and f,g are \(\mathcal {C}^{\infty}(\mathcal{M})\). This gives a notion of directional derivative of a vector field defined on the manifold. An affine connection extends naturally to more than vector fields, and especially of interest here, covariant tensors: if h is a covariant p-tensor and \(X\in{\frak{X}}(\mathcal {M})\), ∇ X h is defined as follows. Given p vector fields \(Y_{1},\dots,Y_{p}\in{\frak{X}} (\mathcal{M})\),

(57)

(57) -

-

6.

Covariant derivatives: Let \(\mathcal{M}\) be a differentiable manifold with affine connection ∇. There exists a unique correspondence which associates to a vector field V along the differentiable curve \(c:I\to\mathcal{M}\) another vector field \(\frac{DV}{dt}\) along c, called the covariant derivative of V along c, such that

-

\(\frac{D}{dt}(V+W) = \frac{DV}{dt} + \frac{DW}{dt}\), where W is a vector field along c.

-

\(\frac{D}{dt}(fV) = \frac{df}{dt}V + f\frac{DV}{dt}\), where f is a differentiable function on I.

-

If V is induced by a vector field Y, a member of the tangent bundle of \(\mathcal{M}\), i.e. V(t)=Y(c(t)), then \(\frac{DV}{dt} = \nabla_{\frac{dc}{dt}} Y\).

The covariant derivative extends to covariant tensors via the extension of the connection to them: Given a covariant p-tensor h defined along c and vector fields U 1,…,U p along c,

(58)

(58) -

-

7.

Parallel transport: Given a vector \(P\in T_{c(0)}\mathcal{M}\), the differential equation

(59)

(59)admits a unique solution, called the parallel transport of P along c. The induced map P↦P(t) from \(T_{c(0)}\mathcal{M}\) to \(T_{c(t)}\mathcal {M}\) is a linear isomorphism.

The parallel transport extends to covariant tensors in the same way: Given a p-linear mapping \(h:T_{c(0)}\mathcal{M}\times\dots\times T_{c(0)}\mathcal{M}\to \mathbb{R}\), the differential equation

(60)

(60)admits a unique solution, called the parallel transport of h along c. As for vectors, the mapping h↦h(t) is a linear isomorphism between p-linear maps on \(T_{c(0)}\mathcal{M}\) and p-linear maps on \(T_{c(t)}\mathcal{M}\).

-

8.

Levi-Civita connection: Given a Riemannian metric g on the manifold \(\mathcal{M}\), there exists a unique affine connection ∇ such that

-

compatibility with the metric:

$$ X.g(Y,Z) = g(\nabla_XY,Z) + g(X, \nabla_X Z) $$(61) -

symmetry:

(62)

(62)([X,Y] is the Lie bracket of X and Y).

∇ is the Levi-Civita connection associated to g. Note that from the previous items, one has ∇ X g=0 for any \(X\in{\frak{X}}(\mathcal {M})\) and that the parallel transport in that case is a linear isometry.

The compatibility of ∇ and the metric g can be expressed in term of covariant derivatives: if X(t)=X(c(t)) and Y(t)=Y(c(t)) are two vector fields along the curve c, and D/dt is the covariant derivative along c,

$$ \frac{d}{dt}g\bigl(X(t),Y(t)\bigr) = g \biggl( \frac{DX(t)}{dt},Y(t) \biggr) + g \biggl(X(t),\frac{DY(t)}{dt} \biggr). $$(63) -

-

9.

Christoffel symbols: In a parametrised manifold, where the curve c(t) is represented as (x 1(t),…,x M(t)), the covariant derivative of a vector field v becomes

$$ \frac{Dv}{dt} = \sum_m \biggl\{ \frac{dv^m}{dt} + \sum_{i,j}\varGamma_{ij}^m v^j\frac{dx^i}{dt} \biggr\} \frac{\partial}{\partial x_m}, $$(64)where the \(\varGamma_{ij}^{m}\) are the coefficients of the connection also known as the Christoffel symbols Γ. In particular, the parallel transport equation above becomes the first-order linear system

(65)

(65)For the Levi-Civita connection associated with the metric g, the corresponding Christoffel symbols are given by

$$ \varGamma_{ij}^m = \frac{1}{2}\sum _{l} \biggl\{\frac{\partial}{\partial x_i}g_{jm} + \frac{\partial}{\partial x_j}g_{mi} - \frac{\partial}{\partial x_m}g_{ij} \biggr \}g^{ml} $$(66)g ij is the ijth element of the metric, and g ij is the ijth element of its inverse. A curve is geodesic if the covariant derivative of its tangent vector field is zero everywhere on it, which means that a geodesic curve has zero tangential acceleration. Such a curve c satisfies the second order system of ODEs, which, with the above parametrisation becomes

$$ \frac{d^2x^m}{dt^2} + \sum_{ij} \varGamma^m_{ij}\frac{dx^i}{dt}\frac {dx^j}{dt} = 0,\quad m=1\dots M. $$(67) -

10.

Exponential map: The exponential map is a map \(\operatorname{Exp}: T\mathcal{M}\to\mathcal{M}\), that maps \(v \in T_{q}\mathcal{M}\) for \(q \in\mathcal{M}\), to a point \(\operatorname{Exp}_{q}v\) in \(\mathcal{M}\) obtained by going out the length equal to |v|, starting from q, along a geodesic which passes through q with velocity equal to \(\frac{v}{|v|}\). Given \(q \in\mathcal{M}\) and \(v\in T_{q}\mathcal{M}\), and a parametrisation (x 1,…,x n ) around q, \(\operatorname{Exp}_{q}(v)\) can be defined as the solution at time 1 of the above system of ODEs (67) with initial conditions (x m(0))=q and \((\frac{dx^{m}}{dt}(0)) = v\), m=1,…,M. The geodesic starting at q with initial velocity t can thus be parametrised as

(68)

(68) -

11.

Logarithm map: For \(\tilde{q}\) in a sufficiently small neighbourhood of q, the length minimising curve joining q and \(\tilde{q}\) is unique as well. Given q and \(\tilde{q}\), the direction in which to travel geodesically from q in order to reach \(\tilde{q}\) is given by the result of the logarithm map \(\operatorname{Log}_{q}(\tilde{q})\). We get the corresponding geodesics as the curve \(t\mapsto \operatorname{Exp}_{q}(t\operatorname{Log}_{q}\tilde{q})\). In other words, \(\operatorname{Log}\) is the inverse of \(\operatorname{Exp}\) in the neighbourhood.

Appendix B: Numerical Implementation of Exponential Maps and Parallel Transports

In this appendix, we briefly review some techniques for numerical implementation of exponential Maps and parallel transports. We have applied them in the articulated tracking example in Sect. 4.3. As logarithm maps are not used, they will not be described here. It is worth noticing that the numerical techniques presented in the following are easily adapted to other manifolds, though care should be taken in, e.g., step size selection when the manifold is highly curved.

2.1 B.1 Computing Exponential Maps

Assume \(\mathcal{M}\) is an M-dimensional sub-manifold of ℝN and that the metric is inherited from the standard inner product in ℝN. We can then discretise the geodesics in a straight-forward manner. We remind the reader that, given a vector v in the tangent space of the point x 0, the exponential map seeks a point \(\operatorname{Exp}_{\mathbf{x}_{0}} (\mathbf{v})\) on the geodesic curve starting at x 0 with the same length and direction as v.

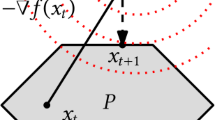

We then discretise the geodesics in a straightforward way by applying a standard forward Euler scheme based on the standard projection method [11]. The method repeatedly takes a discrete step in the tangent space in the direction encoded by v followed by a projection back onto the manifold. The latter is necessary as the discrete step will “fall of the manifold” unless \(\mathcal{M}\) is flat. This scheme is illustrated in Fig. 16. The missing piece is a scheme for projecting a point in the embedding space back onto \(\mathcal{M}\). Defining projection of \(\hat{\mathbf{x}} \in\mathbb{R}^{N}\) as finding the nearest point on \(\mathcal{M}\) reduces projection to a non-linear least-squares problem [15],

which can easily be solved using gradient descent [15]. Specifically, we apply a projected steepest descent with line-search, as empirical results have shown it to be both fast and stable [7]. This scheme usually finds a local optimum within a few iterations as it is warm-started with the results from the previous iteration.

In the practical implementation, we use 10 discrete steps in the Euler scheme, where the step length is controlled by the length of the tangent vector and the length of the geodesic segment computed so far. More sophisticated schemes that take local curvature into account might prove beneficial, but we have not experimented with this. We have tried with more discrete steps, but did not notice much improvement; we speculate that this is because we only need to compute short geodesic segments due to the sequential nature of the tracking problem.

2.2 B.2 Computing the Parallel Transport

Given two points x 0 and x I in \(\mathcal{M}\) and the geodesic segment α that joins them, we describe a classical approximation of the parallel transport of a vector \(\mathbf{v}_{0} \in T_{\mathbf{x}_{0}}\mathcal{M}\) to a vector \(\mathbf {v}_{i} \in T_{\mathbf{x}_{I}}\mathcal{M}\) along α, known as Schild’s Ladder [29]. This scheme places points along the geodesic and approximately parallel transports v 0 to these by forming approximate parallelograms on \(\mathcal{M}\).

Let {x 1,…,x I−1} denote points along the geodesic segment joining x 0 and x I . Then start by computing \(\mathbf {a}_{0} = \operatorname{Exp}_{\mathbf{x}_{0}} (\mathbf{v}_{0})\) and the midpoint b 1 of the geodesic segment joining x 1 and a 0 (see the left side of Fig. 17). Follow the geodesic from x 0 through b 1 for twice its length to the point a 1. This scheme is repeated for all sampled points along the geodesic from x 0 to x I (see the right side of Fig. 17). The final parallel transport of v 0 can then be evaluated as the logarithm map \(\operatorname{Log}_{\mathbf{x}_{I}} (\mathbf{a}_{I})\). When sampled points are available along the geodesic segment from x I to a I , this logarithm map can easily be approximated using the finite difference of the velocity at x I .

As we use the standard projection method for computing the geodesic which we transport along, we form approximate parallelograms between the discrete points on the geodesic. As with the exponential maps we do not seem to experience numerical problems caused by curvature of the manifold, most likely due to the short geodesics that occur as part of tracking. For more difficult parallel transportation problems, we believe that more sophisticated numerical schemes are needed.

Appendix C: Proof of Proposition 1

We need to show that \(\frac{DM_{t}}{dt} = 0\). It will be sufficient to show that

for the vectors v m (t),m=1,…,M defined in the proposition. Indeed, for each t, they form an orthonormal basis of \(T_{\alpha(t)}\mathcal{M}\):

because the v m (t)s are parallel along α, and therefore their covariant derivative vanish. By definition of the covariant derivative for a tensor,

The last two terms vanish, again because the v m (t)s are parallel. On the other hand, a simple calculation gives

(δ mm′ is the usual Kronecker symbol) and this quantity is thus independent of t. This concludes the proof. □

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hauberg, S., Lauze, F. & Pedersen, K.S. Unscented Kalman Filtering on Riemannian Manifolds. J Math Imaging Vis 46, 103–120 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10851-012-0372-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10851-012-0372-9