Abstract

Empirical research in international trade has shown that exporting firms display higher productivity than their non-exporting competitors. This paper focuses on the relation between export and profitability. Our evidence on Italian exporting firms shows that exporting activity is not systematically associated to higher firm’s profitability. This is shown both by means of non-parametric methods and, with an approach that is more standard within the empirical trade literature, by regression techniques that try to identify an “export premium”.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although, at least initially, most of the attention had been placed to manufacturing sectors only, there is now a tendency to consider also the service sectors (Lejour and Smith 2008; Canoy and Smith 2008; Vogel and Wagner 2010) also intended as service to exporting manufacturers (Ahn et al. 2010; Akerman 2010; Bernard et al. 2010).

A disclaimer is due in this respect. Although this is the main idea underpinnings most of the theoretical models, evidence is more blurred. Many empirical works report, for instance, that in the decomposition of sectoral productivity growth, the term that accounts for firms/plants level productivity growth (within term) is bigger than that accounting for the reallocation of market share to more productive firms/plants (between term). See for instance Baily et al. (1992), Foster et al. (2001), and Baldwin and Gu (2006). A similar exercise that provides germane results is that in Bottazzi et al. (2010).

As said, this latter mechanism, that involves ascribing the biggest share of the productivity growth to reallocation, receive more contrasting evidence. For instance the results in Baily et al. (1992) and Baldwin and Gu (2006) report that for Canada and US the main driving force of (industry) productivity growth resides in the firm-level effect (the so-called within effect in the productivity growth decomposition).

Note, however, that they only report evidence on a very small sample (164 firms) of Japanese enterprises.

In between, notice that the euro introduction, which happened during the time interval covered by our database, can be considered as one of such trade liberalization event.

The correlation between productivity (both labor and TFP) and profitability for firms in our sample is positive and significant. Results, not shown here, are available on request.

For the empirical analysis that we present in the paper we have used freely-available software. In particular for the statistical and econometric analysis we have used R (http://www.r-project.org/), gbutils and subbotools developed by Bottazzi (2004).

The database has been made available for work after careful censorship of individual information and was accessible at ISTAT facilities. More detailed information concerning the development of the database Micro.3 are in Grazzi et al. (2009).

Limited liability companies (società di capitali) have to hand in a copy of their financial statement to the Register of Firms at the local Chamber of Commerce in accomplishment to article 2435 of the Civil Code. Then the Union of the Chambers of Commerce gathers the data from local units, and it is this latter database that is finally provided to ISTAT.

Istat provides the time series for the Italian economy at: http://con.istat.it/default.asp.

Notice that the table reports the percentage of exporters in the Micro.3 database which, to repeat, contains information on firms bigger than 20 employees. Also consider that trade data are collected by Istat on every single cross-national transaction, thus we are not introducing any sample bias in the analyses that follow.

The pre-euro period stops in 1995 because from 1996 onward it is already possible to detect a much more stable Italian Lira/Deutsche Mark exchange rate, and some convergence to the level of exchange that was later fixed by the Council of the European Union.

Many measures of multi-factor productivity can in principle be employed—and are actually used also in this work—, sticking to labor productivity prevents from introducing possible biases due to the misspecification of the function representing the technology. Further, the concern for biased regression coefficients due to omitted variables (i.e. technology, capital, work-force skill, etc) is mitigated by recent work by Foster et al. (2001) which shows a close correlation between multi-factor productivity and labor productivity in U.S. See also the estimates in Haltiwanger et al. (1999).

Although there might be reasons to employ only simple labor productivity as a proxy of firm’s efficiency (see previous footnote) we also provide results for Total Factor Productivity so that it is at least possible to compare our results to those of other work that only employ TFP estimates. In this work TFP is computed assuming a simple Cobb–Douglas production function and constant labor and capital shares across firms in the same industry. Capital is proxied by fixed tangible assets at the original historic cost.

Gross Operative Margin is valued added minus wages, salaries, and social insurances paid by the firm.

The size and productivity differentials between exporting and non-exporting firms were already put forward in previous empirical analyses on Italian firms (see, among the others Ferragina and Quintieri 2000; Basile 2001; Sterlacchini 2001; Castellani 2002; Bugamelli and Infante 2003; Serti and Tomasi 2008).

Also consider that, as far as “surviving” firms are concerned, we know that labor productivity is a relatively stable variable (cf. Dosi and Grazzi 2006).

Other tests have been used, also in the literature of international economics to compare the distributions of productivity of different groups of firms, see for instance the work by Delgado et al. (2002), in order to provide a benchmark for comparison, we inform the reader that results for the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) are coherent with those of the FP test. Due to space constraints we do not report in this version of the paper results for KS test, but they are available from the author on request. Whether another application in the field of economics of the FP test can be found in Bottazzi et al. (forthcoming).

Results are largely consistent also with Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Results of this further test are not reported in this version of the paper but are available from the author on request.

In the present work we consider registered patents both at USPTO and EPO. There are 1883 firms with registered patents in our database. Exploratory analysis show that—as expected—patenting activity appears to be positively related to firms’ performance in terms of productivity and profitability (to a less extent), but not in terms of firms’ growth.

In principle it would probably be more senseful to think of a regression model where the export status stands on the left-hand side of the equation, and conversely labor productivity is on the right-hand. Indeed, this would reflect more closely what suggested by the theory: it is those firms that are more productive to start with that, after trade liberalization, are more likely to export. Or to put it in another way, one would like better a model where productivity “causes” a higher probability to export. However, in order to ensure the comparability of our results to those in the literature, we conform to the standard “export premia” regressions where the export dummy is on the right hand side of the equation.

As it could be expected, due to the almost irrelevance of the threshold of export (as shown in Fig. 2), results do not change substantially if considering export share or a dummy that considers a given threshold of export share of total sales.

Parametric and non-parametric Kendall’s Tau correlation coefficients show that this is the case for firms in our sample; further see also Bottazzi et al. (2010).

For the size of the firm, as proxied by sales, we choose the median as indicator of central tendency.

Of course, there are reasons to believe that the well known evidence in favor of the productivity premia for exporting firms is also related to size. For we know that bigger firms are generally more productive (see, for the Italian case, Bottazzi and Grazzi 2010) and we also know that bigger firms are more likely to export. In the parametric analysis that we perform in this work (Section 5) we try to disentangle these effects, for the time being let us focus on the issue of export threshold only.

References

Ahn J, Khandelwal A, Wei S (2010) The role of intermediaries in facilitating trade. Research Paper in Economics 1, Stockholm University, Department of Economics

Akerman A (2010) A theory on the role of wholesalers in international trade based on economies of scope. Working Paper 15706, National Bureau of Economic Research

Aw BY, Chung S, Roberts MJ (2000) Productivity and the decision to export: micro evidence from Taiwan and South Korea. World Bank Econ Rev 14(1):65–90

Baily MN, Hulten C, Campbell D (1992) Productivity dynamics in manufacturing establishments. Brookings Pap Econ Act Microecon 4:187–249

Baldwin JR, Gu W (2006) Plant turnover and productivity growth in canadian manufacturing. Ind Corp Change 15(3):417–465

Bartelsman EJ, Haltiwanger J, Scarpetta S (2009) Measuring and analyzing cross country differences in firm dynamics. In: Dunne T, Jensen JB, Roberts MJ (eds) Producer dynamics: new evidence from micro data. National Bureau of Economic Research Studies in Income and Wealth, Chicago: NBER/ The University of Chicago Press

Basile R (2001) Export behavior of Italian manufacturing firms over the nineties: the role of innovation. Res Policy 30(8):1185–1201

Bernard AB, Jensen BJ (1995) Exporters, jobs, and wages in US manufacturing: 1976–1987. Brookings Pap Econ Act Microecon 1995:67–112

Bernard AB, Jensen BJ (1999) Exceptional exporter performance: cause, effect, or both? J Int Econ 47(1):1–25

Bernard AB, Jensen JB (2004) Why some firms export. Rev Econ Stat 86(2):561–569

Bernard A, Wagner J (1997) Exports and success in german manufacturing. Review of World Economics (Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv) 133(1):134–157

Bernard AB, Eaton J, Jensen JB, Kortum SS (2003) Plants and productivity in international trade. Am Econ Rev 93(4):1268–1290

Bernard AB, Jensen JB, Redding SJ, Schott PK (2007) Firms in international trade. J Econ Perspect 21(3):105–130

Bernard AB, Grazzi M, Tomasi C (2010) Intermediaries in international trade: direct versus indirect modes of export. Research Series 10-199, National Bank of Belgium

Bottazzi G (2004) Subbotools user’s manual. LEM—Working Papers 2004-14, Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna

Bottazzi G, Grazzi M (2010) Wage–size relation and the structure of work-force composition in italian manufacturing firms. Camb J Econ 34(4):649–669

Bottazzi G, Grazzi M, Secchi A (2005) Characterizing the production process: a disaggregated analysis of Italian manufacturing firms. Riv Polit Econ 95(1):243–270

Bottazzi G, Cefis E, Dosi G, Secchi A (2007) Invariances and diversities in the evolution of Italian manufacturing industry. Small Bus Econ 29(1–2):137–159

Bottazzi G, Dosi G, Jacoby N, Secchi A, Tamagni F (2010) Corporate performances and market selection. Some comparative evidence. Ind Corp Change 19(6):1953–1996

Bottazzi G, Grazzi M, Secchi A, Tamagni F (forthcoming) Financial and economic determinants of firm default. J Evol Econ. doi:10.1007/s00191-011-0224-6

Bugamelli M, Infante L (2003) Sunk costs of exports. Temi di discussione (Economic Working Papers), 469, Bank of Italy, Economic Research Department

Canoy M, Smith P (2008) Services and the single market. J Ind Compet Trade 8(3):319–347

Castellani D (2002) Export behavior and productivity growth: Evidence from italian manufacturing firms. Review of World Economics (Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv) 138(4):605–628

Delgado MA, Farina JC, Ruano S (2002) Firm productivity and export market: a non-parametric approach. J Int Econ 57(1):397–422

Dosi G, Grazzi M (2006) Technologies as problem-solving procedures and technologies as input–output relations: some perspectives on the theory of production. Ind Corp Change 15(1):173–202

Dosi G, Grazzi M, Tomasi C, Zeli A (forthcoming) Turbulence underneath the big calm: what is happening behind the flat trend of productivity in Italy. Small Bus Econ J. doi:10.1007/s11187-011-9326-7

Dunne T, Roberts MJ, Samuelson L (1988) Patterns of firm entry and exit in US manufacturing industries. Rand J Econ 19:495–515

Ericson R, Pakes A (1995) Markov-perfect industry dynamics: a framework for empirical work. Rev Econ Stud 62(1):53–82

Ferragina AM, Quintieri B (2001) Caratteristiche delle imprese esportatrici italiane. Un’analisi su dati Mediocredito e Federmeccanica. In: Quintieri B (ed) Processi di internazionalizzazione delle imprese italiane: caratteristiche, performance e innovazione. Bologna, Il Mulino, pp 61–89

Fligner MA, Policello GE (1981) Robust rank procedures for the Behrens–Fisher problem. J Am Stat Assoc 76(373):141–206

Foster L, Haltiwanger JC, Krizan CJ (2001) Aggregate productivity growth. Lessons from Microeconomic Evidence. In: New developments in productivity analysis, NBER Chapters. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc., pp 303–372

Fryges H, Wagner J (2010) Exports and profitability: first evidence for German manufacturing firms. The World Economy 33(3):399–423

Girma S, Greenaway D, Kneller R (2004) Does exporting increase productivity? A microeconometric analysis of matched firms. Rev Int Econ 12(5):855–866

Grazzi M, Sanzo R, Secchi A, Zeli A (2009) Micro.3 some notes on the development of the integrated system of data 1989–2004. Documenti n. 11, Istat

Haltiwanger JC, Lane JI, Spletzer JR (1999) Productivity differences across employers: the roles of employer size, age, and human capital. Am Econ Rev 89(2):94–98

Hopenhayn H (1992) Entry, exit and firm dynamics in long run equilibrium. Econometrica 60:1127–1150

Hsiao C (2007) Panel data analysis–advantages and challenges. TEST 16(1):1–22

Jensen BJ, McGuckin RH (1997) Firm performance and evolution: empirical regularities in the us microdata. Ind Corp Change 6:25–47

Jovanovic B (1982) Selection and the evolution of industry. Econometrica 50(3):649–70

Lejour A, Smith P (2008) International trade in services—editorial introduction. J Ind Compet Trade 8(3):169–180

López RA (2009) Do firms increase productivity in order to become exporters? Oxf Bull Econ Stat 71(5):621–642

Lu J, Beamish P (2006) Sme internationalization and performance: growth vs profitability. J Int Entrep 4:27–48

Mairesse J (2007) Comments on: panel data analysis–advantages and challenges. TEST 16(1):37–41

Mayer T, Ottaviano G (2008) The happy few: the internationalisation of european firms. Intereconomics 43(3):135–148

Melitz MJ (2003) The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica 71(6):1695–1725

Melitz MJ, Ottaviano GIP (2008) Market size, trade, and productivity. Rev Econ Stud 75(1):295–316

Roberts MJ, Tybout JR (1997) The decision to export in Colombia: an empirical model of entry with sunk costs. Am Econ Rev 87(4):545–64

Serti F, Tomasi C (2008) Self-selection and post-entry effects of exports: evidence from Italian manufacturing firms. Rev World Econ (Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv) 144(4):660–694

Sterlacchini A (2001) The determinants of export performance: a firm-level study of Italian manufacturing. Rev World Econ (Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv) 127(3):450–472

Temouri Y, Vogel A, Wagner J (2010) Self-selection into export markets by business services firms: evidence from france, germany and the united kingdom. IZA Discussion Papers 5147, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA)

Vogel A, Wagner J (2010) Exports and profitability—first evidence for german business services enterprises. Appl Econ Q 56(1):7–30

Wagner J (2002) The causal effects of exports on firm size and labor productivity: first evidence from a matching approach. Econ Lett 77(2):287–292

Wagner J (2007) Exports and productivity: a survey of the evidence from firm-level data. The World Economy 30(1):60–82

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges helpful comments and discussions with Giovanni Dosi, Chiara Tomasi and thanks two anonymous referees. The statistical exercises presented in the paper would not have been possible without the valuable help of the Italian Statistical Office (ISTAT) and in particular of Roberto Monducci and Alessandro Zeli. The research leading to these results has received funding from MIUR, PROT. 2007HA3S72_003, PRIN 2007. The usual disclaimers apply.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Thresholds for export status

Appendix: Thresholds for export status

In the paper we content ourselves with a definition of exporter as that of any firm that in a given year has reported a positive fraction of turnover (however small) from sales abroad. Table 1 reported the percentage of exporting firms without considering any threshold of export intensity, and so did the distributional analysis in Fig. 1.

The purpose of this Appendix is to investigate if the results we obtain in the paper significantly depend on the definition of exporter. Scholars have investigated the issue of export intensity in relation to performance variables, most notably firm’s productivity (see, among the others, Aw et al. 2000; Castellani 2002; Bernard et al. 2003 and Fryges and Wagner 2010 on profitability), however the literature does not, nor the empirical evidence, provide conclusive results. Another relevant dimension in order to try answering our original question, is the time window. A firm that is willing to expand by going international will have to pay a sunk cost of entry, which is also specific to each destination country.Footnote 25 As such we do expect that once a firm has taken such a decision, and paid the relative entry cost, it will tend to persist in the export market for some years to follow. Thus, a further distinction that might turn useful for understanding who are “exporters” is that between “systematic” exporters, those firms that once have started to export then persist in the export market, and “occasional” exporters, those firms that are sporadically active on the international markets.

We concentrate on those sectors accounting for a relevant share of national exports (as shown in Table 3) and among these, we will choose sectors also in order to provide a representative picture of the whole manufacturing industry in Italy. To this end we consider the sectors of Manufacture of textile (NACE 17), Basic metals (NACE 27), Machinery and equipment n.e.c. (NACE 29) as they satisfy these criteria, and in addition these sectors also have a high number of observations.

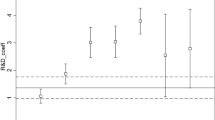

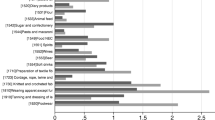

Plots in Fig. 2 display a measure of central tendency of some performance variables, namely size as proxied by total sales, productivity (labor and TFP), profitability, and growth, for firms exporting more than a given threshold of their turnover. The aim is to better understand if beyond a certain threshold of export intensity we do observe a given pattern in the variable of interest. In particular, our interest is to verify if the differences between the two groups of firms, exporters and non exporters, arise after some threshold of export intensity, or if, on the contrary, the only discriminant cutoff is the export status, irrespectively of its intensity.

Row I: median size (as total sales in thousands of euro) at different threshold of export intensity. Row II: real average labor productivity at different threshold of export intensity. Row III: average profitability (as ROS) at different threshold of export intensity. Row IV: average one-year growth rates at different threshold of export intensity

Every dot in the graphs represents the averageFootnote 26 value of a given variable for firms exporting more than x% of their sales. Of course, we are aware that the performance variables that we are investigating are not normally distributed and they do display a very wide support (see for instance Bottazzi et al. 2005, 2007) so that sometimes the mean is a noisy indicator. In principle, one would want to compare at every threshold of export intensity the whole distribution of a variable for exporters and for non exporters in order to get a more precise assessment of the differences between the two groups.

Let us now consider the relation between different thresholds of export intensity and the median size of firms associated to that threshold. Many empirical works show that bigger firms are more likely to be exporters (Serti and Tomasi 2008; Bernard et al. 2007; Castellani 2002), and this is shown also in the plots in the first row of Fig. 2. Such a gap persists also at higher level of export intensity. Also notice that in the machine tool sector (NACE 29) after the clear gap that identifies firms starting to export, we do observe a slight increase of the median size at higher export intensities. The other sectors included in the analysis do not display such a feature.

The relation between labor productivity and export intensity is represented by plots in the second row of Fig. 2. For firms in the textile sector, NACE 17, in 2000 and 2004 the average labor productivity of all non-exporters was around 35 thousands euro (deflated with the sectoral production price index) as marked by the corresponding dots at the extreme left of the plot. A relevant “productivity premium” characterizes exporting firms. Again such difference has more to do with export status than export intensity. The average labor productivity of all firms exporting any positive share of their turnover is, both in 2000 and 2004, around 40 thousands euro, registering an increase of 15% with respect to non-exporting firms. This is very robust evidence, as it holds across all sectors included and is valid for all years.Footnote 27 Again, one notices that in the sector of machine tool, NACE 29, intensive exporters appear to be more productive than marginal exporters, and that the trend is linear. Results for TFP are much in line with those on labor productivity, in particular this is surprisingly so for the sector of machine tool, NACE 29.

Plots in fourth row of Fig. 2 compare the profitability of non-exporters to that of firms with different intensity of export. As far as profitability is concerned we do register, in most sectors and years, the opposite trend: exporters report lower profitability. The same lack of relationship is also apparent between export and firms’ growth, as displayed by the plots in the fifth and last row of Fig. 2.

Let us now consider the issue of persistency over time in the export status. To this purpose, in the following we define a firm as “systematic” exporter in 2004 if it has exported in 3 or more of the previous 5 years. We define accordingly a firm as “occasional” exporter if it has exported only once or twice in the same time interval, and residually, non exporters are those firms that never exported in these years. Since the database we employ for trade data, COE, contains information on all cross-border transactions performed by Italian firms, we are safe that we are not inducing any selection bias in the analysis by employing these definitions.

Plots in Fig. 3 display the empirical density of total sales, labor and TFP, return on sales and growth rates in 2004 for firms as classified in the categories of “systematic”, “occasional” exporters, and never exporters on the basis of their export activity in the previous five years. From the plots it is apparent that “systematic” exporters are bigger in all the industrial sectors that we consider, Textile, NACE 17, Basic Metal, NACE 27, and Machine tool, NACE 29. Further it is clear that there exists a ranking between the three groups of firms that holds in all sectors: “systematic” exporters are bigger than “occasional” exporters, and the latter are bigger than never exporters. The same ranking is observable also for the distributions of labor and TFP, whether, as in the plots of Fig. 1, the export activity is not apparently associated to better performance in terms of profitability or growth.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grazzi, M. Export and Firm Performance: Evidence on Productivity and Profitability of Italian Companies. J Ind Compet Trade 12, 413–444 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-011-0102-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-011-0102-9

Keywords

- trade

- export premium

- systematic and occasional exporters

- productivity

- profitability

- international competition