Abstract

Knowledge of mobility is essential for understanding animal habitat use and dispersal potential, especially in the case of species occurring in fragmented habitats. We compared within-patch movement distances, turning angles, resting times, and flight-related morphological traits in the locally endangered butterfly, the dryad (Minois dryas), between its old populations occupying xerothermic grasslands and newly established ones in wet meadows. We expected that the latter group should be more mobile. Individuals living in both habitat types did not differ in their body mass and size, but those from xerothermic grasslands had wider thoraxes and longer wings, thus lower wing loading index (defined as body mass to wing length ratio). The majority of movements were short and did not exceed 10 m. Movement distances were significantly larger in males. However, there was no direct effect of habitat type on movement distances. Our results suggest that the dryads from xerothermic grasslands have better flight capabilities, whereas those from wet meadows are likely to invest more in reproduction. This implies that mobility is shaped by resource availability rather than by recent evolutionary history. Lower female mobility may have negative implications for the metapopulation persistence because only mated females are able to (re)colonise vacant habitat patches efficiently. Conservation efforts should thus be focused on maintaining large habitat patches that prevent stochastic local extinctions. Furthermore, the recommendation of promoting the exchange of individuals among patches through improving matrix permeability, as well as assisted reintroductions of the species into suitable vacant habitats should also improve its conservation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For most animals, mobility is a crucial trait that allows them to find basic resources such as mating partners, food or shelter. Moreover, mobility enables many animals to persist in increasingly fragmented and heavily altered environments in which more and more species are forced to live (Fahrig 2003; Foley et al. 2005; Concepcion et al. 2008). Due to such environmental changes individuals must be able to reach habitat patches with the essential resources in order to survive (Fahrig 2003; Thomas et al. 2004; Dover and Settele 2009). Within-patch mobility enhances local population resilience to the habitat disturbance and may also be an indication of the potential exchange of individuals between local populations which supports metapopulation persistence (Hanski and Ovaskainen 2000; Kraus et al. 2003). Individuals with large mobility may potentially explore all available resources within a habitat patch as well as utilise those that are widespread in different habitats (Dennis et al. 2003; Auckland et al. 2004; Kalarus et al. 2013).

Several insect studies revealed that flight performance is strongly associated with morphological traits (Berwaerts et al. 2002; Merckx and Van Dyck 2002). For instance, it was found that butterflies from newly established populations have longer wings (Merckx and Van Dyck 2002) and are characterized by increased mobility (Hanski et al. 2006). However, it remains unknown if morphological traits are also related to mobility at a very local, within-habitat patch scale.

Knowledge of mobility is especially important in the case of endangered species occurring in small and isolated local populations, which are surrounded by an inhospitable matrix (Mathias et al. 2001; Thomas et al. 2001; WallisDeVries 2004). One such species is a specialist butterfly, the dryad Minois dryas (Scopoli 1763). In Poland, the occurrence of this species is restricted to few isolated localities in the south of the country, including the Kraków region, where it survives in protected calcareous xerothermic grasslands, and more recently has spread into surrounding wet meadows (Dąbrowski 1999; Kalarus et al. 2013). Therefore, it is worth to examine whether the dryads living in wet meadows differ in mobility and flight morphology from those inhabiting xerothermic grasslands. It can be expected that the individuals from former group should be more mobile and cover longer distances, which should also be reflected in their morphology since they are the descendants of the most dispersive butterflies and their mobility is likely to possess a substantial genetic component (Hill et al. 1999; Merckx et al. 2003; Haag et al. 2005).

The aim of our study was to investigate differences in within-patch movements and flight morphology between the dryads from xerothermic and wet habitats. In addition, we focused on inter-sexual differences in mobility, which are typically strong in butterflies, but often neglected (Ovaskainen et al. 2008; Nowicki and Vrabec 2011; Schultz et al. 2012). Specifically, for both habitat types and sexes we compared (1) movement distances and turning angles; (2) morphological traits possibly associated with butterfly mobility (body mass, forewing length, thorax width, wing loading index, and general body size index); (3) resting times, which are inversely related to flight activity. Based on the results obtained we also provide practical conservation recommendations for the dryad.

Methods

Fieldwork

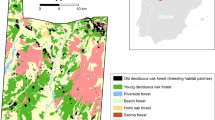

The survey was carried out during the flight period of the dryad, i.e. August, in 2009 and 2010. Four habitat patches were selected for the study. Two of them are xerothermic grasslands: Skołczanka (site A, 1.01 ha) and Uroczysko Kowadza (site B, 0.72 ha). The other two are nearby wet meadows (site C, 4.41 ha; site D, 1.04 ha). The inter-patch distances within the pairs of patches of the same type are 80 m (for wet meadows) to 180 m (for xerothermic grasslands), whereas both pairs lie 200–400 apart. All the investigated sites are located within the Bielańsko-Tyniecki Landscape Park and are part of the Natura 2000 site “Dębnicko-Tyniecki Obszar Łąkowy” (PLH 120065). A more detailed description of all four study sites can be found elsewhere (Kalarus et al. 2013).

We examined within-patch movements by the dryads, their resting times between consecutive flights, and morphological traits potentially related to mobility. The movements were recorded from the moment when a spotted butterfly was initially noticed resting on a plant. Butterflies were followed by observers from the distance of about 5 meters in order to avoid disturbing butterflies. Points where the butterfly stopped were subsequently marked with numbered bamboo poles. This made it possible to measure distances of movements and turning angles between them with the help of steel measuring tape and compass. Resting time between consecutive movements was recorded with the precision of one second. Other types of behaviour were very rarely observed and thus were not considered in the present study. After the fifth consecutive movement the butterfly was captured with an entomological net. Thorax width and forewing length were then measured to the nearest 0.1 mm using a Vernier calliper. Finally, each individual was placed in a small envelope and weighted with a TOMOPOL S-50 balance with the precision of 0.005 g. The weighting was repeated twice for each butterfly and averaged. Having taken all the above measurements, we marked the butterfly with a unique number on the underside of its hind wing with a non-toxic permanent marker, and immediately released it. The data from any individual (even if recaptured) were used only once in the analyses to avoid pseudoreplication.

Statistical analysis

Since our survey design was incomplete, i.e. not every site was surveyed in both years of the study; we were not able to test the effects of site and year separately. Thus, we instead adopted the effect of a data set, i.e. data collected at a given site in a particular year, as a random factor in the analyses conducted using generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) with parameter estimates derived using the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) method (Searle et al. 1992; Wolfinger et al. 1994). The data set effect was always nested within habitat type. Nevertheless, in all the cases, it proved insignificant and did not improve the model fit. Consequently, with this effect removed, the final models were reduced to standard general linear models (GLMs).

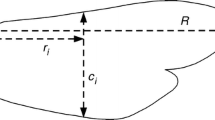

Separate GLMs were applied to test the impacts of habitat type and sex as well as their interaction term on the morphological characteristics of the dryads. The investigated traits included body mass, thorax width, forewing length, wing loading index, and general body size (see below). The traits were derived for the purpose of subsequent analyses as the original traits were clearly positively correlated with one another (ln-transformed body mass vs. thorax width: r = 0.489, P < 0.001; ln-transformed body mass vs. wing length: r = 0.602, P < 0.001; thorax width vs. wing length: r = 0.589, P < 0.001). Wing loading index was defined as the ratio of body mass to forewing length. Applying the classic definition of wing loading (i.e. body mass to wing surface ratio; see Dudley and Srygley 1994) was not possible, because wing surface measurements could not be easily taken in the field, and thus we had to rely on a proxy using wing length instead (as e.g. Tiple et al. 2009). General body size index was calculated as the sum of standardised values of body mass, thorax width and wing length obtained through dividing the measurements by the means for all individuals. Body mass measurements were cubic rooted before standardisation. We decided to rely on the derived index rather than to use body mass as a measure of body size, because butterfly body mass varies (typically decreases) during adult life span, and definitely we were not able to weight all individuals in the same moment of their life, e.g. directly after hatching.

In the next step, further GLMs were built to explain patterns in the average movement distances and resting times. The latter was used as a measure of butterfly inactivity. Both variables were ln-transformed to achieve their normal distribution. Among the predictors the models included butterfly sex, habitat type and their interaction term as fixed effects; as well as wing loading and butterfly size indexes as continuous covariates.

Turning angles were grouped into twelve 30°-wide classes. Their distributions were first tested for inter-sexual differences separately for xerothermic grasslands and wet meadows with Chi square tests. Since there were no significant differences in any case, the data for both sexes were pooled together for further analyses of the turning angle distributions. The distributions were compared between the two habitat types, again using Chi square test. Additionally, the distributions for each habitat type were evaluated against two theoretical distributions: the uniform distribution and the von Mises distribution, which is equivalent to the normal distribution for circular data (Fisher and Best 1979; Batschelet 1981). The uniformity of the turning angle distributions was assessed with the Rao’s spacing test (Mardia and Jupp 2000), whereas the Watson’s U2 test (Zar 1998) was applied to examine whether the distributions were consistent with the von Mises distribution. We also calculated the concentration index K (Fisher and Best 1979) of the turning angle distribution for each habitat type to obtain how the distributions are concentrated around the mean angle. The concentration index K is a measure of the deviation of the angle distribution from a uniform one (Mardia and Jupp 2000). Higher K index values indicate higher concentration of angle distribution.

The GLMs were calculated in JMP 10, while the turning angle analysis was done in the Oriana 3.0 software.

Results

The GLM models for morphological traits indicated strong inter-sexual differences in each case (Table 1). Females of the dryad were heavier, had wider thorax and longer wings, but males had lower wing loading index (Fig. 1). Furthermore these inter-sexual differences were clearly confirmed for body size index in the interaction term habitat type × sex (Fig. 1). Individuals from xerothermic grasslands proved to have longer wings and lower wing loading index than those from wet meadows (Table 1; Fig. 1). In addition, the thorax was significantly wider in the former group, but the difference was evident only in males. For better illustration of morphometric measurements of the dryad butterflies their mean values are shown in Table 2.

The analysis of distances covered by the dryads revealed a significant effect of sex, with males flying further distances than females, but not of habitat type (Tables 2, 3; Fig. 2). The majority of movement distances were quite short (>10 m) and very few exceeded 20 m, especially in females (Fig. 2).

In general, females tended to rest longer than males (Tables 2, 4). Although habitat type alone did not affect the resting times of butterflies, its interaction with sex was highly significant (Table 4). The GLM model results also implied a positive relationship between wing loading index and resting time (Table 4; Fig. 3). With this relationship accounted for, resting times were the longest in females from wet meadows and the shortest in males from the same habitat, while there was no particular difference between resting times of both sexes in xerothermic grasslands (Fig. 4).

Inter-sexual differences in resting times (mean ± SE) of the dryad in both investigated habitats. White and grey bars represent females and males respectively. To account for the significant relationship between butterfly wing loading index and resting time, the values presented are residuals of this relationship

Distributions of turning angles did not differ between sexes in any habitat (xerothermic grasslands: χ2 = 4.251, P = 0.962; wet meadows: χ2 = 5.700, P = 0.893). However, with the data for both sexes pooled together, they did so between both habitats (χ2 = 21.281, P = 0.031; Fig. 5). Furthermore, the Rao’s spacing test outcome showed that the distributions were clearly not uniform, but instead they were consistent with the von Mises distribution as suggested by the insignificant Watson’s U2 test results (Table 5). In both habitat types the great majority of turning angles were centred near 0 (Fig. 5; see also relatively high values of the concentration index K in Table 5), which indicates that butterflies tended to move in fairly straight lines without much change in the flight direction.

Discussion

Numerous earlier studies have documented the relationship between morphological traits of various butterfly species and their mobility. Specifically, it has been found that mobility is negatively affected by body mass, but positively by thorax width and wing length (Berwaerts et al. 2002; Skórka et al. 2013). The results of the present study generally confirm the above patterns, although we found that wing loading index is more useful as a factor explaining the dryad mobility. Wing loading index correlated positively, while body size index correlated negatively with resting time, but only the former relationship proved statistically significant.

Comparisons of morphological characteristics between the two investigated habitat types indicated that the dryads from xerothermic grasslands appear more adapted to flight. They had wider thoraxes and longer wings than the individuals from wet meadows, and consequently, lower wing loading index, since there was no difference in body mass between both groups. Nevertheless, despite apparently greater potential mobility of the butterflies inhabiting xerothermic grasslands, habitat type alone had no apparent impact on within-patch movement distances. However, these morphological differences may indicate that dryads from xerothermic grasslands are more capable to successfully migrate from natal patches than butterflies from wet meadows.

There was no clear effect of habitat type on the resting times. Females from wet meadows rested longer, but males rested shorter than the butterflies from xerothermic grasslands. In wet meadows, relatively long resting times in females may force males to take flight more frequently in order to search for mating partners. Taking everything into consideration, while habitat type indirectly affected the dryad mobility through its effect on flight-related morphology, we found no evidence for its additional direct influence on local mobility, although effects may be present on realized dispersal. Moreover, this indirect effect of habitat type was in the opposite direction than expected, i.e. the individuals representing recently established populations in wet meadows turned out to be less mobile.

Consequently, it seems justified to hypothesise that mobility and flight morphology of the dryad within the studied region is shaped by differences in resource availability among habitat patches as a result of phenotypic plasticity (cf. Merckx and Van Dyck 2006), rather than by the recent evolutionary history of the populations inhabiting them. It is known, that availability and quality of foodplants affect morphology of adult individuals (Fischer and Fiedler 2000). In earlier research on the dryad we have demonstrated that xerothermic grasslands offer substantially more nectar sources, whereas wet meadows are generally better in terms of larval foodplant abundance (Kalarus et al. 2013). Since nectar is the predominant source of energy utilised for flight by many butterfly species (Sacktor 1975; Kammer and Heinrich 1978), its increased availability supports highly mobile individuals. In contrast, the dryads living in wet meadows are likely to invest more in reproduction. It is worth noting that thinner thoraxes recorded in this habitat apparently imply larger abdomens, as body mass did not differ between both grassland types. Greater investment in reproduction presumably leads to less investment in flight capacity since a trade-off between both investments should be expected (Gibbs and Van Dyck 2010).

The flight distances of the dryads within their habitat patches were strikingly short in most cases. The movement distances recorded in our study were not only well below distances separating habitat patches, but also considerably shorter than patch dimensions. In addition, the fact that turning angles fitted well with the von Mises distribution indicates that the flight routine followed correlated random walk (Kareiva and Shigesada 1983). Altogether our findings suggest limitations to the dryad movements within their patches (cf. Hovestadt and Nowicki 2008).

Mobility depression in highly fragmented landscapes has been frequently reported in butterflies (Mathias et al. 2001; Hanski and Meyke 2005; Bergerot et al. 2012). The phenomenon has serious conservation implications as it decreases metapopulation viability (Hanski 1999; Russell et al. 2006). In our study system, the situation may be worsened by male-biased mobility. While females are often a more mobile sex in butterflies (e.g. Bergman and Landin 2002; Auckland et al. 2004; Nowicki and Vrabec 2011, but see Junker and Schmitt 2010), we observed the opposite pattern in the dryad. This is a further constraint for the successful conservation of this species because only mated females are able to ensure colonisations of vacant habitat patches, which is a key process for metapopulation persistence. It is also possible that low, male-biased mobility has led to the extinction of the dryad in northern Poland as was earlier reported (Romaniszyn and Schille 1929; Dąbrowski 1994); as well as to its decline in Germany (Settele et al. 1999).

Because the distances covered by the dryad are so low, the colonisation of empty patches may be difficult. The recommended conservation actions should be focused on enhancing the chances of continuous existence of local populations despite presumably low exchange of individuals. This should be achieved through maintaining relatively large habitat patches, which should prevent stochastic extinctions of their populations (Hanski 1999). In addition, the exchange of individuals among habitat patches may be promoted through improving permeability of the matrix. A good quality matrix supports butterfly dispersal as it encourages individuals to emigrate from their habitat patches (Ricketts et al. 2001; Schtickzelle and Baguette 2003). In the case of the dryad, the optimal type of matrix seems to be meadows lacking the foodplants, but rich in nectaring plants. However, as the dryad is also known to utilise sunny deciduous forests with sparse canopy and forest edges (Krzywicki 1982; Warecki and Sielezniew 2008), such habitats may also be useful for dispersal (cf. Streitberger et al. 2012). Finally, potentially poor colonising capabilities of the species should be an argument for its assisted reintroductions into vacant suitable habitats. Such actions spontaneously conducted in recent years, proved to be particularly successful in establishing new viable populations (Dąbrowski 1994).

References

Auckland JN, Debinski DM, Clark RW (2004) Survival, movement, and resource use of the butterfly Parnassius clodius. Ecol Entomol 29:139–149

Batschelet E (1981) Circular statistics in biology. Academic, New York

Bergerot B, Merckx T, Van Dyck H, Baguette M (2012) Habitat fragmentation impacts mobility in a common and widespread woodland butterfly: do sexes respond differently? BMC Ecol 12(1):5

Bergman KO, Landin J (2002) Population structure and movements of a threatened butterfly (Lopinga achine) in a fragmented landscape in Sweden. Biol Conserv 108:361–369

Berwaerts K, Van Dyck H, Aerts P (2002) Does flight morphology relate to flight performance? An experimental test with the butterfly Pararge aegeria. Funct Ecol 16(4):484–491

Buszko J, Masłowski J (2008) Motyle Dzienne Polski. Koliber, Nowy Sącz

Concepcion ED, Diaz M, Baquero RA (2008) Effects of landscape complexity on the ecological effectiveness of agri-environment schemes. Landscape Ecol 23:135–148

Dąbrowski JS (1994) Successful attempts of reintroduction of local populations of Lepidoptera from the species Zygaena carniolica (Zygaenidae) and Minois dryas (Satyridae) into protected areas of the southern Poland. Chr Przyr Ojcz 50(2):31–42

Dąbrowski JS (1999) Skalnik driada Minois dryas (Scop.), (Lepidoptera: Satyridae)—gatunek zagrożony wyginięciem na ostatnich znanych stanowiskach w Polsce. Chr Przyr Ojcz 55(4):91–94

Dennis RLH, Shreeve TG, Van Dyck H (2003) Towards a functional resource-based concept for habitat: a butterfly biology viewpoint. Oikos 102:417–426

Dover J, Settele J (2009) The influences of landscape structure on butterfly distribution and movement: a review. J Insect Conserv 13:3–27

Dudley R, Srygley RB (1994) Flight physiology of neotropical butterflies: allometry of airspeed during natural free flight. J Exp Biol 191:125–139

Fahrig L (2003) The effects of habitat fragmentation on biodiversity. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 4:487–515

Fischer K, Fiedler K (2000) Response of the copper butterfly Lycaena tityrus to increased leaf nitrogen in natural food plants: evidence against the nitrogen limitation hypothesis. Oecologia 124:235–241

Fisher NI, Best DJ (1979) Efficient simulation of the von Mises distribution. Appl Stat 28:152–157

Foley JA, De Fries R, Asner GP, Barford C, Bonan G, Carpenter SR, Chapin FS, Coe MT, Daily GC, Gibbs HK, Helkowski JH, Holloway T, Howard EA, Kucharik CJ, Monfreda C, Patz JA, Prentice IC, Ramankutty N, Snyder PK (2005) Global consequences of land use. Science 309:570–574

Gibbs M, Van Dyck H (2010) Butterfly flight activity affects reproductive performance and longevity relative to landscape structure. Oecologia 163(2):341–350

Haag CR, Saastamoinen M, Marden JH, Hanski I (2005) A candidate locus for variation in dispersal rate in a butterfly metapopulation. P Roy Soc Lond B 272:2449–2456

Hanski I (1999) Metapopulation ecology. Oxford University Press, New York

Hanski I, Meyke E (2005) Large-scale dynamics of the Glanville fritillary butterfly: landscape structure, population processes, and weather. Ann Zool Fenn 42(4):379–395

Hanski I, Ovaskainen O (2000) The metapopulation capacity of a fragmented landscape. Nature 404:755–758

Hanski I, Saastamoinen M, Ovaskainen O (2006) Dispersal-related life-history trade-offs in a butterfly metapopulation. J Anim Ecol 75(1):91–100

Hill JK, Thomas CD, Blakeley DS (1999) Evolution of flight morphology in a butterfly that has recently expanded its geographic range. Oecologia 121:165–170

Hovestadt T, Nowicki P (2008) Investigating movement within irregularly shaped patches: analysis of MRR data using randomisation procedures. Isr J Ecol Evol 54:137–154

Junker M, Schmitt T (2010) Demography, dispersal and movement pattern of Euphydryas aurinia (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) at the Iberian Peninsula: an alarming example in an increasingly fragmented landscape? J Insect Conserv 14:237–246

Kalarus K, Skórka P, Nowicki P (2013) Resource use in two contrasting habitat types raises different conservation challenges for the conservation of the dryad butterfly Minois dryas. J Insect Conserv 17(4):777–786

Kammer AE, Heinrich B (1978) Insect flight metabolism. Adv Insect Physiol 13:133–228

Kareiva PM, Shigesada M (1983) Analyzing insect movement as a correlated random walk. Oecologia 56:234–238

Krauss J, Steffan-Dewenter I, Tscharntke T (2003) Local species immigration, extinction, and turnover of butterflies in relation to habitat area and habitat isolation. Oecologia 142:591–602

Krzywicki M (1982) Monografia motyli dziennych polski. Papilionidea i Hesperoidea, Lublin

Mardia KV, Jupp PE (2000) Statistics of directional data, 2nd edn. John Wiley & Sons, Chicester

Mathias A, Kisdi E, Olivieri I (2001) Divergent evolution of dispersal in a heterogeneous landscape. Evolution 55(2):246–259

Merckx T, Van Dyck H (2002) Interrelations among habitat use, behaviour, and flight-related morphology in two co-occurring Satyrine butterflies, Maniola jurtina and Pyronia tithonus. J Insect Behav 15:541–561

Merckx T, Van Dyck H (2006) Landscape structure and phenotypic plasticity in flight morphology in the butterfly Pararge aegeria. Oikos 113:226–232

Merckx T, Van Dyck H, Karlsson B, Leimar O (2003) The evolution of movements and behaviour at boundaries in different landscapes: a common arena experiment with butterflies. Proc R Soc B 270(1526):1815–1821

Nowicki P, Vrabec V (2011) Evidence for positive density-dependent emigration in butterfly metapopulations. Oecologia 167:657–665

Ovaskainen O, Luoto M, Ikonen I, Rekola H, Meyke E, Kuussaari M (2008) An empirical test of a diffusion model: predicting clouded apollo movements in a novel environment. Am Nat 171:610–619

Ricketts TH, Daily GC, Ehrlich PR, Fay JP (2001) Countryside biogeography of moths in a fragmented landscape: biodiversity in native and agricultural habitats. Conserv Biol 15(2):378–388

Romaniszyn J, Schille F (1929) Fauna motyli Polski (Fauna Lepidopterorum Poloniae). 1. Prace Monograficzne Komisji Fizjograficznej 6, p 57

Russell GJ, Diamond JM, Reed TM, Pimm SL (2006) Breeding birds on small islands: island biogeography or optimal foraging? J Anim Ecol 75:324–339

Sacktor B (1975) Biochemistry of insect flight. 1. Utilization of fuels by muscle. In: Candy DJ, Kilby BA (eds) Insect biochemistry and function. Chapman and Hall, London, pp 1–88

Schtickzelle N, Baguette M (2003) Behavioural responses to habitat patch boundaries restrict dispersal and generate emigration-patch area relationships in fragmented landscapes. J Anim Ecol 72:533–545

Schultz CB, Franco AMA, Crone EE (2012) Response of butterflies to structural and resource boundaries. J Anim Ecol 81:724–734

Searle SR, Casella G, McCulloch CE (1992) Variance components. Wiley, New York

Settele J, Feldmann R, Reinhardt R (eds) (1999) Die tagfalter Deutschlands. Ulmer, Stuttgart

Skórka P, Nowicki P, Kudlek J, Pepkowska A, Sliwinska EB, Witek M, Woyciechowski M (2013) Movements and flight morphology in the endangered large blue butterflies. Cent Eur J Biol 8:662–669

Streitberger M, Hermann G, Kraus W, Fartmann T (2012) Modern forest management and the decline of the woodland brown (Lopinga achine) in Central Europe. Forest Ecol Manag 269:239–248

Thomas JA, Bourn NAD, Clarke RT, Stewart KE, Simcox DJ, Pearman GS, Curtis R, Goodger B (2001) The quality and isolation of habitat patches both determine where butterflies persist in fragmented landscapes. P Roy Soc Lond B 268:1791–1796

Thomas CD, Cameron A, Green RE, Bakkenes M, Beaumont LJ, Collingham YC, Erasmus BF, De Siqueira MF, Grainger A, Hannah L, Hughes L, Huntley B, Van Jaarsveld AS, Midgley GF, Miles L, Ortega-Huerta MA, Peterson AT, Phillips OL, Williams SE (2004) Extinction risk from climate change. Nature 427:145–148

Tiple AD, Khurada AM, Dennis RLH (2009) Adult butterfly feeding–nectar flower associations: constraints of taxonomic affiliation, butterfly, and nectar flower morphology. J Nat Hist 43:855–884

WallisDeVries MF (2004) A quantitative conservation approach for the endangered butterfly Maculinea alcon. Conserv Biol 18:489–499

Warecki A, Sielezniew M (2008) Dryad Minois dryas (Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae) in south-eastern Poland: a recent range expansion or oversight of an endangered species? Pol J Entomol 77:191–198

Wolfinger R, Tobias R, Sall J (1994) Computing Gaussian likelihoods and their derivatives for general linear mixed models. SIAM J Sci Comput 15(6):1294–1310

Zar JH (1998) Biostatistical analysis, 4th edn. Prentice Hall, New Jersey

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the Polish National Science Centre Grant No. N304 064139 and by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research under its FP6 BiodivERsA Eranet project CLIMIT. The fieldwork was additionally supported by the Jagiellonian University through its DS/WBINOZ/INOŚ/761/09-10 funds as well as by the Bratniak Foundation. The authors are grateful to the students of the Jagiellonian University and the volunteers, especially Katarzyna Czober and Jakub Osika who participated in the fieldwork. We also thank Bernard Kromka for improving the English in the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kalarus, K., Skórka, P., Halecki, W. et al. Within-patch mobility and flight morphology reflect resource use and dispersal potential in the dryad butterfly Minois dryas . J Insect Conserv 17, 1221–1228 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-013-9603-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-013-9603-7