Abstract

This paper investigates the impact of tourism flows on demand for large regional and city theatres in Austria over the period from 1972 to 2011 (39 years). The results are obtained by applying an aggregated theatre demand function for both residents and tourists. The elasticity of theatre attendance in response to tourism is estimated along with other standard demand variables such as ticket price and income. The quality factors and theatre-specific effects are also included. The tourism flows variables are derived using detailed data set on tourist arrivals and their overnight counts, and they are also split between domestic and foreign tourists. To measure the impact of tourism flows on theatre demand, three alternative theatre markets specifications are considered. The total elasticity of attendance per capita in response to tourism is estimated between 15 and 20 %, indicating that increasing the number of arrivals by two tourists per resident in the relevant market would generate an increase in theatre attendance by 581–680 thousand visitors per year. The role of tourism flows is found to be particularly important for attendance at opera, operetta and musicals as opposed to attendance at drama performances. The analysis also reveals that foreign, non-German tourists have a positive impact on theatre attendance, whereas domestic tourists do not contribute significantly to higher demand for Austrian theatres.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

According to Tourism—Satellite Account, the tourist expenditures in Austria contributed overall to 7.5 % of GDP in 2010.

See Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft, Familie und Jugend (2011) for more details.

The paper uses somewhat similar data on Austrian theatres to those applied in Zieba (2011), albeit for a longer time period from 1972/1973 to 2010/2011 (39 years). The paper also differs substantially from the previous study not only by investigating the effects of tourism flows on demand for Austrian theatres but it also uses different dependent variables, and it provides estimates for attendance at different types of performances.

See Zieba (2009) for an exact definition of price of leisure and its application to estimating the demand for German public theatre.

Data on Austrian theatres were included for the first time in Theaterstatistik 1969/1970, and they are listed in this report the same way every year. This allows the comparison of data over time.

According to information available in Theaterstatistik, the typical theatre season lasts 12 months, from 1 August until 31 July of the following calendar year. However, in some cases, the season might be shorter as theatres reduce their activities during the summer (i.e. they play from beginning of September until around July), and so they prepare their repertoire in July and August for the new season.

In state-owned theatres, the management is usually appointed by the theatre’s licence holder. In the case of theatres with private ownership, external governmental institutions are entitled to control them.

All examined theatres also have their own venues which often consist of one large and several small auditoriums granted to them by the state, municipalities and federal regions in Austria.

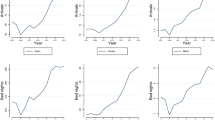

It should be noted that similar pattern of attendance can be observed in the data when attendance is normalised using the per capita terms. Therefore, the figures for the normalised data are not presented.

The exact name of the data source is “STATcube—Statistische Datenbank der STATISTIK AUSTRIA”.

Approximately 1600 reporting municipalities (around two-thirds of Austrian municipalities) submit data on monthly arrivals and overnight stays by guests from Austria and abroad who stay in around 75,000 commercial and private accommodation establishments.

NUTS is an abbreviation for "Nomenclature des unités territoriales statistiques". This system divides the territory of the EU into territorial units on three levels, which normally consist of entire administrative units or groupings of such units: NUTS1 Regions of the European Communities, NUTS2 Basic administrative units and NUTS3 Subdivisions of the basic administrative units.

The discussion of what we might expect by loosening the constraint is presented in Sect. 4.1.3.

The federal regions in Austria are geographically large units, and they are also rather homogenous in their population and income structure. Most of the cities in which the theatres are located are the actual capitals of the federal provinces. The only exception is the theatre in Baden (“Stadttheater Baden”) which is located on the border between two federal regions, and in this instance, the market for the theatre may extend to the neighbouring districts such as Vienna. For this theatre, both specifications were empirically tested, but the results did not differ.

It should be noted that this measure includes visitors attending performances staged by foreign ensembles, but it does not include attendance at guest performances.

The art genre “opera” was combined together with category “operettas and musicals” as they produced the same results with regard to all variables discussed.

The Austrian Shilling was pegged against the German Mark since 1976 and was relatively stable until Austria became an official member of European Monetary Union (EMU) in 1999. For the period prior to joining the EMU, the ticket price measured in Austrian Shilling was converted into EUR values using the official conversion rate of 1 EUR = 13,7603 ATS.

The Veblen effect which means a positive demand response due to an increase in ticket price is rather unrealistic for tourists attending the performing arts but could be valid, for example, for tourists acquiring works of art.

In order to control for both the relative price differences and nominal exchange rate fluctuations, following Dritsakis (2012) we included in the demand model the real effective exchange rate index for Austria, but the variable was not significant.

These capacity constraints apply mainly to two small auditoriums for two theatres in Vienna. We run the model by excluding these observations and the results did not change.

Including separate dummy variables for the location of each theatre will be dropped from the model due to collinearity with the individual theatre dummies. However, we also estimate the model using the dummy variables for the location instead of dummy variables for theatres and we find similar results.

For the first and the second market specifications, this involves weighting the tourism flows of the current year by 5/12 and the flows of the following calendar year by 7/12. For the third market specification, the tourists arrivals per season are obtained by adding 5 months of the current year (August–December) and 7 months of the following year (January–July). To account for the fact that some theatres do not play in July and August as they prepare for the new season, we also use a 10-month season as an alternative specification.

The data on total disposable income of households in Austria were not available for the required time period at NUTS-3 level. The data on gross domestic product (GDP) were available for the period 2000–2011 for both federal regions (NUTS2) and the smaller territorial units (NUTS3) in Austria. For 1969–1999, the country level data were available and the values for NUTS2 and NUTS3 units were obtained using the average shares (calculated on the basis of data available for the later period).

The log-linear model was chosen since a substantially better statistical fit was obtained through the use of the logarithmic transformation of all variables as compared to a simple linear function. The logarithmic transformation has also the advantage as the estimates of determinants of demand can be interpreted as direct partial elasticities.

In the long-panel case, the cluster robust standard errors are no longer valid. Another alternative would be to use the Newey–West corrected standard errors. However, assuming that the model for serial correlation in the error term is correct, the FGLS estimator is more efficient asymptotically. In our case, both specifications are applied and deliver identical results with the exception of the magnitude of the ticket price coefficient which is 0.15 % lower in the Newey–West specification. Thus, we present the results for the FGLS model only.

O’Hagan and Zieba (2010) applied a dynamic difference GMM estimator in order to correct for possible endogeneity bias and the results varied little from those using the fixed-effects estimator.

These results are not presented as the estimates of all other remaining explanatory variables in the demand model for drama performances were very similar to those presented in the paper.

Serial correlation of order 1 but not higher was confirmed by Wooldridge’s (2002) test for linear panel data.

The number of artists was in the end excluded from the demand models presented in Table 5 as it was never significant and highly correlated with décor and costumes variable. This might be due to the fact that this variable refers to all artistic staff in a theatre and not specifically to those playing at opera, operetta and musical performances.

References

Ateca-Amestoy, V. (2008). Determining heterogeneous behavior for theatre attendance. Journal of Cultural Economics, 33(2), 85–108.

Borowiecki, K. J., & Castiglione, C. (2014). Cultural participation and tourism flows: an empirical investigation of Italian provinces. Tourism Economics, 20(2), 241–262.

Bull, A. (1995). The economics of travel and tourism (2nd ed.). Melbourne: Addison Wesley Longman Australia Pty Ltd.

Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft, Familie und Jugend. (2011). Tourismus in Österreich 2011. Ein Überblick in Zahlen. http://www.bmwfw.gv.at/Tourismus/TourismusInOesterreich/Documents/Tourismus%20in%20O%CC%88sterreich%202011_HP.pdf.

Carey, S., Davidson, L., & Sahli, M. (2013). Capital city museums and tourism flows: An empirical study of the museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. International Journal of Tourism Research, 15, 554–569.

Craik, J. (1997). The culture of tourism. In C. Rojek & J. Urry (Eds.), Touring cultures: Transformations of travel and theory (pp. 114–136). London: Routledge.

Divisekera, S., & Deegan, J. (2010). An analysis of consumption behaviour of foreign tourists in Ireland. Applied Economics, 42, 1681–1697.

Dritsakis, N. (2012). Tourism development and economic growth in seven Mediterranean countries: A panel data approach. Tourism Economics, 18(4), 801–816.

Gapinski, J. (1984). The economics of performing Shakespeare. The American Economic Review, 74(3), 458–466.

Gapinski, J. (1986). The lively arts as substitutes for the lively arts. The American Economic Review, 76(2), 20–25.

Gapinski, J. (1988). Tourism contribution to the demand for London’s lively arts. Applied Economics, 20, 957–968.

Gorman, W. M. (1959). Separable utility and aggregation. Econometrica, 27(3), 469–481.

Grisolía, J. M., & Willis, K. G. (2012). A latent class model of theatre demand. Journal of Cultural Economics, 36(2), 113–139.

Gruber, K., & Köppl, R. (1998). The theatre system of Austria. In Hans van Maanen & Steve Wilmer (Eds.), Theatre worlds in motion. Structures, politics and developments in the countries of Western Europe (pp. 37–73). Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Hall, M., & Zeppel, H. (1990). Cultural and heritage tourism: The new grand tour? Historic Environment, 7, 86–98.

Kim, H., Cheng, Ch-K, & O’Leary, J. T. (2007). Understanding participation patterns and trends in tourism cultural attractions. Tourism Management, 28, 1366–1371.

Laamanen, J.-P. (2013). Estimating demand for opera using sales system data: The case of Finnish National Opera. Journal of Cultural Economics, 37(4), 417–432.

McIntyre, C. (2007). Survival theory: Tourist consumption as a beneficial experiential process in a limited risk setting. International Journal of Tourism Research, 9(2), 115–130.

McKercher, B. (2002). Towards a classification of cultural tourists. International Journal of Tourism Research, 4, 29–38.

Moore, T. (1966). The demand for broadway theatre tickets. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 48(1), 79–87.

O’Hagan, J., & Zieba, M. (2010). Output characteristics and other determinants of theatre attendance—An econometric analysis of German data. Applied Economics Quarterly, 56(2), 147–174.

Richards, G. (1996). The scope and significance of cultural tourism. In G. Richards (Ed.), Cultural tourism in Europe (pp. 19–46). Wallingford: CAB International.

Seaman, B. (2006). Empirical Studies of Demand for the Performing Arts. In V. Ginsburgh & D. Throsby (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of art and culture (Vol. 1, pp. 416–472). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Stylianou-Lambert, T. (2011). Gazing from home: Cultural tourism and art museums. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(2), 403–421.

Toma, M., & Meads, H. (2007). Recent evidence on the determinants of concert attendance for mid-size symphonies. Journal of Economics and Finance, 31(3), 412–421.

Werck, K., & Heyndels, B. (2007). Programmatic choices and the demand for theatre: The case of Flemish theatres. Journal of Cultural Economics, 31(1), 25–41.

Willis, K. G., & Snowball, J. D. (2009). Investigating how the attributes of live theatre production influence consumption choices using conjoint analysis: The example of the national arts festival, South Africa. Journal of Cultural Economics, 33(3), 167–183.

Withers, G. (1980). Unbalanced growth and the demand for performing arts: An econometric analysis. Southern Economic Journal, 46(3), 735–742.

Wooldridge, J. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. London: MIT Press.

Zieba, M. (2009). Full-income and price elasticities of demand for German public theatre. Journal of Cultural Economics, 33(2), 85–108.

Zieba, M. (2011). Determinants of demand for theatre tickets in Austria and Switzerland. Austrian Journal of Statistics, 40(3), 209–219.

Zieba, M., & O’Hagan, J. (2013). Demand for live orchestral music—The case of German Kulturorchester. Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik, 233(2), 225–245.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the editors and one anonymous referee for the valuable comments. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Barcelona Workshop on Regional and Urban Economics: Cultural Tourism and Sustainable Urban Development, held by AQR-IREA Research Group. The participants of this workshop are thanked for their insightful discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

See Table 7.

Appendix 2: Aggregate theatre demand model for residents and tourists

Following Gapinski (1988), we assume that the quantity of cultural experiences demanded by a resident (y r ) depends on the ticket price (P), price of substitutes (Ps) and his/her disposable income (Inc r ), and thus, it is equal to: \(y_{r} = \alpha_{r} + \alpha_{pr} P + \alpha_{sr} Ps + \alpha_{I} Inc_{r}\) and the quantity of cultural experiences demanded by a tourist (q t ) is equal to: \(q_{t} = \alpha_{t} + \alpha_{pt} P + \alpha_{st} Ps + \alpha_{E} Exp_{t}\) where P and Ps are the ticket price and the prices of substitutes, respectively, and Exp t is the tourist expenditure. Given R residents and T tourists, the total demand for cultural experiences must be equal to \(Y = \sum\nolimits_{r = 1}^{r = R} {y_{r} } + \sum\nolimits_{t = 1}^{t = T} {q_{t} }\) or alternatively can be written as:

Furthermore, assuming that the price coefficients are the same for both residents and tourists (thus α pr = α pt and α sr = α st ) and dividing the Eq. (2) by the number of residents (so that y = Y/R), we obtain the number of cultural experiences per resident which is given by Eq. (3):

where I is the income per resident, E is the total tourist expenditures per resident and TR = T/R is the ratio of tourists divided by the number of residents. The shifts coefficient of interest is α tr and denotes the impact of tourism on theatre attendance per resident.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zieba, M. Tourism flows and the demand for regional and city theatres in Austria. J Cult Econ 40, 191–221 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-015-9250-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-015-9250-9

Keywords

- Cultural tourism

- Tourism flows

- Elasticity of theatre attendance in response to tourism

- Austrian theatres