Abstract

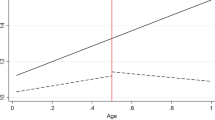

The Droit de Suite, known in the UK as Artists’ Resale Rights, provides an artist with the inalienable right to receive a royalty based on the resale price of an original work of art. This paper provides an empirical analysis of actual changes in the UK auction market for art that is newly subject to the Droit de Suite (DDS) because of a change in law. All changes are measured relative to changes for art not subject to the DDS and relative to changes in the auction markets for art in countries where there has been no change in law. We do a difference-in-difference analysis, differencing price growth and sales growth across market segments and across countries over the period 1993–2007. Our results suggest that the introduction of the DDS has not had a consistent negative impact on the UK art auction market during the period of study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In French, droit de suite means “right to follow”.

The DDS is currently implemented in most European countries, with the exception of Switzerland. The DDS is not payable in the US or in Japan. On June 9, 2010, Australia implemented legislation providing for the DDS.

The UK adopted Directive 2001/84/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the resale right for the benefit of the author of an original work of art on 27 September 2001. The directive was published in the Official Journal of the European Communities on 13 October 2001: L272, Volume 44 (page 32). The UK implemented the Artist’s Resale Right on 14 February 2006 by Statutory Instrument 2006 No. 346. This document can be accessed at http://www.opsi.gov.uk/si/si2006/20060346.

The dealer market is opaque and its size is unclear. One study estimated that the art market in the UK is evenly split between auctions and dealers (Kusin and Company 2002). However, in another measure, undocumented sources indicated that collection houses in the UK were collecting less than 20% of DDS revenue from dealers. Unless DDS has impacted on the decision to sell through a dealer rather than an auction house, the omission of prices from dealers should not have a material effect on our results.

Solow (1998) presents an interesting argument for the DDS: there may be some rise in subsequent prices because of the increased incentive to maintain the value of their work in the future (i.e. they will not overproduce, as predicted by the Coase conjecture), though this is a second-order effect.

A different approach would compare price growth in the period when the DDS was under consideration in the UK with a previous period, such as 1986–1996, before implementation of the DDS was given serious consideration in the UK. However, the volatility of the art market was very high during this period due to the run-up in prices in 1989 (see Ashenfelter and Graddy 2003 or Mei and Moses 2002) and the volatility of Contemporary Art, even relative to Impressionist and Modern Art, was especially high during the end of the 1990s. Furthermore, due to taste changes for art over time, cross-country and cross-market comparisons are more likely to be valid than comparisons over 10-year time periods.

In an earlier version of the paper (Graddy and Banterghansa 2009) we use data from 1996 to the present. We find very similar results with both data sets.

The art market in the UK can be divided into two segments, art sold by public auction and art sold by dealers. Public art auctions are controlled by a small number of auction houses, and the public nature of the transactions make it easy to analyze this segment in some detail. Sales by dealers are not publicly verifiable.

Hislop’s Art Sales Index is a widely used and respected source of data on fine art sales. Specifically, it covers sales of paintings, prints, works on paper, sculptures, miniatures, and photographs by all of the major auction houses worldwide.

The dates for periods four, five and six were used as part of a study for the UK patent office on the implementation of the DDS in the UK. Please see Graddy and Szymanski (2005) and Graddy et al. (2008). Periods one through three were chosen in order to present two periods before the 2001 EU directive on the DDS.

Original sales of art by the artist are not subject to the DDS. Only after the first transfer of ownership does the DDS come into force. It is very, very rare that the first sale of a work of art takes place at auction (an unusual exception was the Damien Hirst single-sale auction that took place in the autumn of 2008). We do not control for original sales by the artist, but due to the rarity of this event, this omission should not at all affect our results.

We downloaded the painting date, but that was only available for about half of the observations. Furthermore, this variable was not significant when it was included in a regression using the subsample for which the variable was available. The insignificance is not surprising, as the prices are demeaned by artist.

Note that we use all of the characteristics that were used in Chanel et al. (1996). In addition, we include medium of painting. While other hedonic analyses have been able to include other characteristics such as sign or stamped and lot number (e.g. see Beggs and Graddy 1997), we were not able to easily download these characteristics from Art Sales Index.

Kraeussl and van Elsland (2008), as implemented in Kraeussl and Lee (2010), have proposed an alternative method for dealing with the problem of too many artist dummy variables. However, as we are interested only in the indices for this study, and not the coefficients on the individual artist dummies, demeaning the regressors is a sufficient correction, especially as it results in an identical index as if artist dummy variables had been included as regressors.

As is usual when constructing price indices, all analyses in both the hedonic and repeat sales regressions are in nominal terms.

The price growth per year is calculated as exp(coef[period 6]1/10) − 1.

In any earlier version of the paper (see Graddy and Banterghansa 2009), we started in 1996. At the request of a referee, we have now extended our data back to 1993, with very similar results.

Depending on how the dataset is constructed, time between sales can range from 3 to 28 years (see Beggs and Graddy 2009). The 20-year period was chosen arbitrarily, but it does give some feel for the magnitude of the impact on returns that should be felt with the introduction of the DDS.

Mei and Moses (2002, 2005) construct their database by searching through auction catalogs from 1950 to 2000 for sales that list a prior sale in their provenance, and then going back to the catalogs for the sale in which the provenance was listed. While the Mei and Moses dataset is excellent in its size, scope, and accuracy, assembling such a dataset is very time-consuming and expensive. Given our database, we have proceeded with the matching method described above.

This methodology was developed by Bailey et al. (1963) and used by Case and Shiller (1987) and Hosios and Pesando (1991) for the real estate market, and subsequently used by Goetzmann (1993), Pesando (1993), Mei and Moses (2002), Goetzmann and Spiegel (2003) and Beggs and Graddy (2008) for the art market.

The average return per year is calculated as exp(μ)1/13, where μ is the sum of the coefficients on each period. This is a lower bound to the average per period growth rate, as the average return per year is calculated as exp(μ + σ2/2)1/13, where σ 2 is the variance in the error term of the repeat sales regressions (2) above. Goetzman (1993) and Mei and Moses (2002) use the coefficient on the second stage Case and Shiller regressions as an estimate of σ 2, but this requires an i.i.d. assumption on the errors of the repeat sales regressions. We prefer to note the growth rate as a lower bound.

References

Ashenfelter, O., & Graddy, K. (2003). Auctions and the price of art. Journal of Economic Literature, 41, 763–787.

Asimow, M. (1971). Economic aspects of the droit de suite. In M. Nimmer (Ed.), Legal rights of the artist. National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities, Washington D.C.

Bailey, M. J., Muth, R. F., & Nourse, H. O. (1963). A regression method for real estate price index construction. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 58, 933–942.

Bays, C. W. (2008). Does a resale royalty benefit artists? The case of California. Unpublished manuscript, East Carolina University.

Beggs, A., & Graddy, K. (1997). Declining values and the afternoon effect: Evidence from art auctions. Rand Journal of Economics, 28, 544–565.

Beggs, A., & Graddy, K. (2008). Failure to meet the reserve price: The impact on the returns to art. Journal of Cultural Economics, 32, 301–320.

Beggs, A., & Graddy, K. (2009). Anchoring effects: Evidence from art auctions. American Economic Review, 99, 1027–1039.

Bolch, B. W., Damon, W. W., & Hinshaw, C. E. (1978). An economic analysis of the California art royalty statute. Connecticut Law Review, 10, 689–701.

Case, K. E., & Shiller, R. J. (1987). Prices of single-family homes since 1970: New indexes for four cities. New England Economic Review, September–October, 45–56.

Chanel, O., Gerard-Varet, L.-A., & Ginsburgh, V. (1996). The relevance of hedonic price indices: The case of paintings. Journal of Cultural Economics, 20, 1–24.

Colonna, C. M., & Colonna, C. G. (1982). An economic and legal assessment of recent visual artists’ reversion rights agreements in the United States. Journal of Cultural Economics, 6, 77–85.

Filer, R. K. (1984). A theoretical analysis of the economic impact of artists’ resale royalties legislation. Journal of Cultural Economics, 8, 1–28.

Ginsburgh, V. (2005a). The DDS. An economic viewpoint. In The modern and contemporary art market. Maastricht: The European Fine Art Foundation.

Ginsburgh, V. (2005b). The economic consequences of the droit de suite in the European union. Economic Policy and Analysis, 35, 61–71.

Goetzmann, W. N. (1993). Accounting for taste: Art and financial markets over three centuries. American Economic Review, 83, 1370–1376.

Goetzmann, W. N., Renneboog, L., & Spaenjers, C. (2010). Art and money, mimeo.

Goetzmann, W. N., & Spiegel, M. (2003). Art market repeat sales indices based upon Gabrius S.P.A. data. Gabrius white paper.

Graddy, K., & Banterghansa, C. (2009). The impact of the droit de suite in the UK: An empirical analysis. CEPR working paper DP7136.

Graddy, K., & Szymanski, S. (2005). A study into the likely impact of the implementation of the resale right for the benefit of the author of an original work of art. IP Institute working paper.

Hansmann, H., & Santilli, M. (1997) Authors’ and artists’ moral rights: A comparative legal and economic analysis. Journal of Legal Studies, 26, 95–144.

Hauser, R. (1962). The French droit de suite: The problem of protection for the underprivileged artist under the copyright law. Copyright Law Symposium, 11, 1–27.

Hosios, A., & Pesando, J. (1991). Measuring prices in resale housing markets in Canada: Evidence and implications. Journal of Housing Economics, 1, 303–317.

Graddy, K.; Horowitz, N., & Szymanski, S. (2008). A study into the effect on the UK art market of the introduction of the artist’s resale right. IP Institute working paper.

Karp, L., & Perloff, J. (1992). Legal requirements that artists receive resale royalties. International Review of Law and Economics, 13, 163–177.

Kraeussl, R., & Lee, J. (2010). Art as an investment: The top 500 artists, mimeo.

Kraeussl, R., & van Elsland, N. (2008). Constructing the true art market index—A novel 2-step hedonic approach and its application to the german art market, mimeo.

Kusin and Company. (2002). The European art market in 2002: A survey. Helvoirt, The Netherlands: TEFAF.

McAndrew, C., & Dallas-Conte, L. (2002). Implementing droit de suite (artists’ resale rights) in England. The Arts Council of England.

Mei, J., & Moses, M. (2002). Art as an investment and the underperformance of ‘master-pieces’. American Economic Review, 92, 1269–1281.

Mei, J., & Moses, M. (2005). Vested interest and biased price estimates: Evidence from an auction market. Journal of Finance, 60, 2409–2435.

Merryman, J. M., Elsen, A., & Urice, S. (2007). Law, ethics and the visual arts, 5e (pp. 579–612). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Law International.

Pesando, J. (1993). Art as an investment: The market for modern prints. American Economic Review, 83, 1075–1089.

Price, M. (1968). Government policy and economic security for artists: The case of the Droit de Suite. Yale Law Journal, 77, 1333–1366.

Solow, J. L. (1998). An economic analysis of the droit de suite. Journal of Cultural Economics, 22, 209–226.

Tepper, J. D. (2007). The droit de suite: An unartistic approach to American law. Available at http://www.works.bepress.com/jonathan_tepper/1.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Rachel Campbell, Rachel McColluch, Dan Tortorice and participants in the Faculty Workshop at Brandeis University and the SEA session on the Economics of Art for very helpful comments on this paper. We would also like to thank two referees at the Journal of Cultural Economics for very helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Banternghansa, C., Graddy, K. The impact of the Droit de Suite in the UK: an empirical analysis. J Cult Econ 35, 81–100 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-010-9134-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-010-9134-y