Abstract

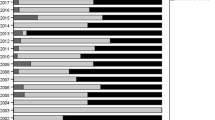

In January 2016, Melissa Cook, a California gestational surrogate experiencing a multiple-birth pregnancy following the in vitro fertilization (IVF) transfer of three embryos comprised of donor eggs and sperm provided by the intended father, went to the media when the intended father requested that she undergo a fetal reduction because twins were less expensive to raise than triplets. Much of the legal interest in this case to date has centered on the enforceability of surrogacy contracts. However, the Cook case also raises troubling issues about fertility treatment practices involving gestational surrogates, twin preference, and third-party reproduction medical decision-making. This paper focuses on multiple-embryo transfers in the context of US surrogacy arrangements. Offering an original analysis of data obtained from the US national-assisted reproduction registry, it examines single- and multiple-embryo transfer trends over a 12-year period (2003 to 2014). Findings reveal that recommended guidelines were followed in fewer than 42% of the cases in 2014. The paper argues that ensuring equitable medical treatment for all recipients of IVF requires the adoption of treatment guidelines tailored to, and offering protections for, specific patient groups, and that, once in place, guidelines must be robustly implemented.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Traditional English children’s nursery rhyme, c 1780.

Bever L. I am pro-life: A surrogate mother’s stand against ‘reducing’ her triplets. Washington Post. January 7 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2016/01/07/i-am-not-having-an-abortion-a-surrogate-mothers-stand-against-reducing-her-triplets/

Melissa K Cook v. Cynthia Anne Harding United States District Court Central District of California, Case No. 2:16-cv-00742 ODW (AFM) June 6, 2016.

Johnson v. Calvert (1993) [No. S023721. May 20, 1993].

California, AB-1217, C.466 Surrogacy Arrangements, (2011–2012).

Gabry LI. Procreating out pregnancy: surrogacy and the need for a comprehensive regulatory scheme. C J Law Soc Probs. 2012;45:415–50.

O’Reilly, K. When parents and surrogates disagree on abortion. The Atlantic. February 18 2016. http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2016/02/surrogacy-contract-melissa-cook/463323/

Storrow R. Surrogacy American style. In Surrogacy, law and human rights. In Gerber P. O’Byrne K., editors. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. 2015, 193–216.

Ragoné H. Incontestable motivations. In Franklin S. Ragoné H., editors, Reproducing reproduction: kinship, power and technological innovation. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998, pp.118-31.

Gugucheva M. Surrogacy in America. Council for Responsible Genetics: Cambridge Mass. 2010. www.councilforresponsiblegenetics.org

Perkins KM, Boulet SL, Jamieson DL, Kissin DM. Trends and outcomes of gestational surrogacy in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2016;106:435–42.

White PM. Hidden from view: Canadian gestational surrogacy practices and outcomes, 2001–2012. Reprod Health Matters. 2016;24:205–17.

Jones HW, Schnorr JA. Multiple pregnancies: call to action. Fertil Steril. 2001;75:11–3.

Davidson CM. Octomom and multi-fetal pregnancies: why federal legislation should require insurers to cover in vitro fertilization. William Mary J Women Law. 2010;17:135–86.

Kawwass JF, Monsour M, Crawford S, Kissin DM, Session DR, Kulkarni AD, et al. Trends and outcomes for donor oocyte cycles in the United States, 2000–2010. J Am Med Assoc. 2013;310(22):2426–34.

Acharya KS, Keyhan S, Acharya CR, Yeh JS, Provost MP, Goldfarb JM, et al. Do donor oocyte cycles comply with ASRM/SART embryo transfer guidelines? An analysis of 13,393 donor cycles from the SART registry. Fertil Steril. 2016;103:603–7.

Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act of 1992 (FCSRC) Pub, L No.102-493 (October 24, 1992).

Price F. Establishing Guidelines and Regulations: The Clinical management of Fertility. In Birthright: Law an Ethics at the Beginning of Life. In R. Lee R. Morgan D. editors, London: Routledge. 1989, p.42.

Seppälä M. The world collaborative report on in vitro fertilization and embryo replacement: current state of the art in January 1984. In Seppälä M. and R.G. Edwards R.G. editors. In Vitro Fertilisation and Embryo Transfer. Annals of New York Academy of Science 1985; 442: 558–63.

Price F. Establishing guidelines and regulations: the clinical management of fertility. In Birthright: law an ethics at the beginning of life. In R. Lee R. Morgan D. editors, London: Routledge. 1989, pp. 37–55.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Educational bulletin. Special problems of multiple gestation. International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1989 (revised 1999) 64:323–33.

Lemonick MD. Septuplets: it’s a miracle. Time Magazine December 1 1997. http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,987455,00.html

Schreuder C. Fertility experts see a dark side to the septuplets’ birth controls needed, some ethicists say. Chicago Tribune. 1997. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1997-11-23/news/9711230361_1_fertility-treatment-septuplets-babies.

Christie J. Party for seven! Record-breaking McCaughey septuplets turn 18 and prepare to graduate high school. Daily Mail. 2015. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3237111/Party-seven-Record-breaking-McCaughey-septuplets-turn-18-prepare-graduate-high-school.html.

Before the Medical Board of California Department of Consumer Affairs, State of California In the Matter of the First Amended Accusation Against Michael Kamrava MD. Physician and Surgeon Certificate No. G41227. Agency Case No. 06-2009-197098. OAH Case No. 2010010877. 2011. http://documents.latimes.com/michael-kamrava-disciplinary-decision.

Robertson JA. Procreative liberty and harm to offspring in assisted reproduction. Am J Law Med. 2004;30:7–40.

Manninen BA. Parental, medical, and sociological responsibilities: “Octomom” as a case study in the ethics of fertility treatments. J Clin Res Bioeth. 2011;S1:002. doi:10.4172/2155-9627.S1-002.

Daar J. Federalizing embryo transfers: taming the wild west of reproductive medicine? C J Gend Law. 2012;23:257–325.

Cahn NR. Collins JM. Eight is enough. Northwestern University Law Review Colloquy 2009; 103: 501–13.

Schieve LA, Meikle SF, Ferre C, Peterson HB, Jeng G, Wilcox LS. Low and very low birth weight in infants conceived with use of assisted reproductive technology. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:731–7.

Pharoah PO. Risk of cerebral palsy in multiple pregnancies. Clin Perinatol. 2006;33:301–13.

Expert Panel on Infertility and Adoption. 2009. Raising expectations. Toronto: Ontario Government.

MacKay AP, Berg JC, King JC, Duran C, Chang J. Pregnancy-related mortality among women with multifetal pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:563–8.

Sazonova A, Källen K, Thurin-Kjellberg A, Ulla-Britt Wennerholm U-B, Bergh C. Neonatal and maternal outcomes comparing women undergoing two in vitro fertilization (IVF) singleton pregnancies and women undergoing one IVF twin pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:731–7.

Stillman RJ, Richter KJ, Jones Jr HW. Refuting a misguided campaign against the goal of single-embryo transfer and singleton birth in assisted reproduction. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:2599–607.

Koivurova S, Hartikainen AL, Gissler M, Hemminki, Klemetti R, Jarvelin MR. Health care costs resulting from IVF: prenatal and neonatal periods. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2798–805.

Klock SC. Psychological adjustment to twins after infertility. Best practice and research. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2004;18:645–56.

Bissonnette F, Phillips S, Gunby J, Holzer H, Mahutte N, St-Michel P, et al. Working to eliminate multiple pregnancies: a success story in Québec. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;23:500–4.

CBC News. Quebec in vitro fertilization: a breakdown of new restrictions on treatment. 2015. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/quebec-ivf-treatment-new-law-1.3317682.

Ferraretti AP, Goossen V, de Mouzon J, Bhattacharya S, Castilla JA, Korsak V, et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2008: results generated from European registers by ESHRE. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:2571–84.

Chambers GM, Hoang VP, Sullivan EA, Chapman MG, Ishihara O, Zegers-Hochschild F, et al. The impact of consumer affordability on access to assisted reproductive technologies and embryo transfer practices: an international analysis. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:191–8.

De Neubourg D, Bogaerts K, Wyns C, Albert A, Camus M, et al. The history of Belgian assisted reproduction technology cycle registration and control: a case study in reducing the incidence of multiple pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:2709–19.

Karletröm PO, Bergh C. Reducing the number of embryos transferred in Sweden: Impact on delivery and multiple birth rates. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:2202–7.

Velez MP, Connelly MP, Kadoch IJ, Phillips S, Bissonnette F. Universal coverage of IVF pays off. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:1313–9.

Kresowick JD, Stegmann BJ, Sparks AE, Ryan GL, van Voorhis BJ. Five years of mandatory single-embryo transfer (mSET) policy dramatically reduces twinning rate without lowering pregnancy rates. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:1367–9.

Harbottle S, Hughes C, Cutting R, Roberts S, Brison D, On behalf of the Association of Clinical Embryologists & The (ACE) British Fertility Society (BFS). Elective single embryo transfer: an update to UK best practice guidelines. Hum Fertil. 2015;18:165–83.

Regina (Assisted Reproduction and Gynaecology Centre and Another) v Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority [2013] EWHC 3087 (Admin) [2013] WLR (D) 416.

Martin JR, Bromer JG, Sakkas D, Patrizio P. Insurance coverage and in vitro fertilization outcomes: a U.S. perspective. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:964–9.

Buckles KS. Infertility insurance mandates and multiple birth rates. Health Econ. 2013;22:775–89.

Boulet SL, Crawford S, Zhang Y, Sunderham S, Cohen B, Bernson D, et al. Embryo transfer practice and perinatal outcomes by insurance mandate status. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:403–9.

Crawford S. Boulet SL. Jamieson DL. Stone C. Mullen J. Kissin DM. Assisted reproductive technology use, embryo transfer practices and birth outcomes after infertility insurance mandates: New Jersey, and Connecticut. Fertility and Sterility 2016;105: 347–55 at 349.

Monteleone PAA, Mirisola RJ, Gonçalves SP, Baracat EC, Serafini PC. Outcomes of elective cryopreserved single or double embryo transfers following failure to conceive after fresh single embryo transfer. Reprod Biomed Online. 2016;33:161–7.

Tremellen K, Wilkinson D, Savulescu J. Is mandating elective single embryo transfer ethically justifiable in young women? Reprod BioMed Soc Online. 2016;1:81–7.

Adamson D. Regulation of assisted reproductive technologies in the United States. Family Law Q. 2005;39:727–44.

Preisler A. Assisted reproductive technology: the dangers of an unregulated market and the need for reform. DePaul J Health Care Law. 2013;15:213–36.

Thompson C. Making parents: the ontological choreography of reproductive technologies. Cambridge: Mass: MIT Press; 2005.

Jain T. Missmer SA. Hornstein MD. Trends in embryo-transfer practice and in outcomes of the use of assisted reproductive technology in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine 2004; 350: 1639–45 at 1642.

Tasdemir M, Tasdemir I, Kodama H, Fukuda J, Tanaka T. Two instead of three embryo transfer in in-vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:2155–8.

Roest JP, Mous HVH, van Heusden AM, Zeilmaker GH, Verhoeff A. A triplet pregnancy after in vitro fertilization is a procedure-related complication that should be prevented by replacement of two embryos only. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:290–5.

Templeton A, Morris JK. Reducing the risk of multiple births by transfer of two embryos after in vitro fertilitzation. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:573–7.

Viska S, Tiitinen A, Hyden-Granskog C, Hovatta O. Elective transfer of embryo results in an acceptable pregnancy rate and eliminates the risk of multiple births. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:2392–5.

Martin JA. Park MA. Trends in twin and triplet births: 1980–97. National Vital Statistics Reports September 14 1999; 47(24). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Ryan M. The cost of longing. 2001. Georgetown University Press.

American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Practice Committee opinion: guidelines on number of embryos transferred. Birmingham, AL: American Society for Assisted Reproductive Medicine; 1998.

American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Practice Committee opinion: guidelines on number of embryos transferred. Birmingham, AL: American Society for Assisted Reproductive Medicine; 1999.

Practice Committee of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Guidelines on the number of embryos transferred. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:773–84.

Stern JE, Ceders MI, Jain T. Assisted reproduction technology practice patterns and the impact of embryo transfer guidelines in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2007;88:275–82.

Practice Committee of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Guidelines on number of embryos transferred. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:S51–2.

Practice Committee of Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Guidelines on number of embryos transferred. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:S163–4.

Stillman RJ. The Suleman octuplets: what can an aberration teach us? Fertil Steril. 2010;93:341–3.

Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Practice Committee of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. Guidelines on number of embryos transferred. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1518–9.

Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Practice Committee of Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. Criteria for number of embryos to transfer: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:44–6.

Kissin DM, Kulkarni AD, Mneimneh A, Warner L, Boulet SL, Crawford S, et al. Embryo transfer practices and multiple births resulting from assisted reproductive technology: an opportunity for prevention. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:954–61.

Practice Committee of Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, and Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Elective single-embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:835–42.

Kulkarni AD, Jamieson DJ, Jones Jr HW, Kissin DM, Gallo MF, Macaluso M, et al. Fertility treatments and multiple births in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2218–25.

Hamilton BE. Martin JA. Osterman MJK. Curtin SC. Mathews TJ. Births: final data for 2014. National Vital Statistics Reports 2015; 66. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Tymstra T. At least we tried everything: about binary thinking, anticipated decision regret, and the imperative character of medical technology. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2007;28:131.

Twisk M, van der Veen F, Repping S, Heineman M-J, Korevaar JC, Bossuyt PMM. Preferences of sub-fertile women regarding elective single embryo transfer: additional in vitro fertilization cycles are acceptable, lower pregnancy rates are not. Fertil Steril. 2007;88:1006–9.

Leese B, Denton J. Attitudes towards single embryo transfer, twin and higher order pregnancies in patients undergoing infertility treatment: a review. Hum Fertil. 2010;13:28–34.

Kovacs P. Commentary: will patients accept fewer embryo transfers? Medscape. July 21, 2015.

Teman E. Birthing a mother. Los Angles: University of California Press; 2010.

Ashenden S. Reproblematising relations of agency and coercion: surrogacy. In Gender, agency and coercion. In S. Madhock S. Phillips A. Wilson K. 2013. Bassingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. 2013, pp. 195–218.

Radin M. Contested commodities. 1996. Cambridge, Mass. Harvard University Press.

Shapiro J. For a feminist considering surrogacy, is compensation really the key question? Wash Law Rev. 2014;89:1345–73.

Ainsworth S. Bearing children, bearing risks: feminist leadership for progressive regulation of compensated surrogacy in the United States. Wash Law Rev. 2014;89:1077–123.

Phillips A. Our bodies: whose property? Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2013.

Child–parent Security Act, Assemb. B. 4319, 2015 Assemb., Reg. Sess. (N.Y. 2016)

D’Alton-Harrison R. Mater semper incertus est: who’s your mummy? Medical Law Review 2014. 22, no.3: 357–83.

Hinson DS. McBrien M. Surrogacy across America. Family Advocate 2011–12; 34: 32–6.

Finkelstein A. MacDougall S. Kintominas A. Olsen A. Surrogacy law and policy in the U.S.: a national conversation informed by global lawmaking. Report of the Columbia Law School, Sexuality & Gender Law Clinic. 2016.

American Society for Reproductive Medicine. 2013. Consideration of the gestational carrier: a committee opinion. www.arsm.org.

Practice Committee of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Recommendations for practices utilizing gestational carriers: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:e1–e18.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee Opinion. Family building through gestational surrogacy. Am College Obstet Gynecologists. 2016;660:1–7.

Bernstein G. Unintended consequences: prohibitions on gamete donor anonymity and the fragile practice of surrogacy. Indiana Health Law Rev. 2013;10:291–324.

Söderström-Anttila V. Wennerholm U-B. Loft A. Pinborg A. Aittomaki K. Romundstad LB. Berg C. Surrogacy: outcomes for surrogate mothers, children and the resulting families—a systematic review. Human Reproduction Update 22, 2016; 2: 260–76.

American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Multiple pregnancy and birth: twins, triplets, and high-order multiples: a guide for patients. 2012.

Practice Committee of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Recommendations for practices utilizing gestational carriers: a committee opinion. Fertility and Sterility 2015;103: e1-8 at e3.

Shenfield F, Pennings G, Cohen J, Devroey P, de Wert G, Tarlatzis B. ESHRE task force on ethics and law 10: surrogacy. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:2705–7.

Shenfield F, Pennings G, De Mouzon J, Ferraretti AP, Goossens V. ESHRE’s good practice guide for cross-border reproductive care for centers and practitioners. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:1625–7.

Melissa Kay Cook, et al. v. Cynthia Anne Harding, et al., California Central District Court, 2:16-cv-00742 2016 WL, February 2, 2016 at 52.

National ART Surveillance System (NASS) tabular data provided on request by the Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, August 8, 2015, April 11, 2016, December 16 and 29, 2016.

MedCalc. https://www.medcalc.org/calc/

Schmidt CO, Kohlmann T. When to use the odds ratio or the relative risk? Int J Public Health. 2008;53:165–7.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee Opinion. Family building through gestational surrogacy. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. March 2016; 660:3.

Practice Committee of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Recommendations for practices utilizing gestational carriers: a committee opinion. Fertility and Sterility 2015; 103: e3 and e.5.

Melissa Kay Cook v. Cynthia Anne Harding. Case no. 2:16-cv-00742-ODW (AFM) Document 92,06.06.16. Order Granting Defendants Motions to Dismiss [44,46,54, 60] 2159 at 2165, lines 11–17.

2016 WL 424998 (C.D.Cal.) (Trial Pleading) United States District Court, C.D. California. Los Angeles Division Melissa Kay COOK et al. v. Cynthia Anne Harding M.P.H., et al. No. 2:16-CV-00742 at 62.

Gleicher N. The irrational attraction of elective single-embryo transfer (eSET). Hum Reprod. 2013;28:294–7.

Gleicher N, Kushnir VA, Barad DH. Risks of spontaneously an IVF-conceived singleton and twin pregnancies differ, requiring reassessment of statistics premises favoring elective single embryo transfer (eSET). Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2016;14:25–32.

Beeson D, Darnovsky M, Lippman A. What’s in a name? Variations in terminology of third-party reproduction. Reprod Biomed Online. 2015;31:805–15.

Lupton D. Social worlds of the unborn. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan; 2013.

Fuchs EL, Berenson AB. Screening of gestational carriers in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2016;106:1496–502.

Beck H. The legalization of emotion: managing risk by managing feelings in contracts for surrogate labor. Law Soc Rev. 2015;49:143–77.

Family Building Act H.R. 697, 111th Cong. (1st Sess. 2009).

RESOLVE, 2016. http://www.resolve.org/family-building-options/insurance_coverage/state-coverage.html.

Rosenthal Marie. Aetna follows best practices for IVF procedures: incentives lower multiple births. Managed Healthcare Executive. April 1. 2013.

Johnston J, Gusmano MK, Patrizio P. In search of real autonomy for fertility patients. Health Econ Policy Law. 2015;10:243–50.

Mid-South Insurance Co. vs. Doe, 2:02-1789-18, 274 F.Supp.2d 757 (D.S.C. 07/29/03).

California Family Code, Section 7962 (4).

Robert R. 2011. The common core standards and next chapter in American education. 2011. Cambridge Mass: Harvard Education Press.

Explicit reference to counselling: Virginia (§ 20–156 to 20–165); Texas TFC Chapter 160; Louisiana 2016 HB NO. 1102, Part III D.

Maine (19-A §§ 1931, 1932).

Texas (TFC Chapter 160).

Utah (§ 78B-15-801 to 78B-15-809).

Acknowledgements

Dr. Sheree L. Boulet, Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta provided the data used in this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

White, P.M. “One for Sorrow, Two for Joy?”: American embryo transfer guideline recommendations, practices, and outcomes for gestational surrogate patients. J Assist Reprod Genet 34, 431–443 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-017-0885-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-017-0885-7