Abstract

The focus on animal welfare in society has increased during the last 50 years. Animal welfare legislation and private standards have developed, and today many farmers within animal production have both governmental legislation and private standards to comply with. In this paper intentions and values are described that were expressed in 14 animal welfare legislation and standards in four European countries; Sweden, United Kingdom, Germany and Spain. It is also discussed if the legislation and standards actually accomplish what they, in their overall description and ethics, claimed to do, i.e. if this is followed up by relevant paragraphs in the actual body of the text in the legislation and standards respectively. The method used was an on-line questionnaire from the EconWelfare research project and text analyses. This study shows that the ethical values within a set of legislation or private standards are not always consistently implemented, and it is not always possible to follow a thread between the intentions mentioned initially and the actual details of the legislation or standard. Since values will differ so will also the animal welfare levels and the implications of similar concepts in the regulations. In general, the regulations described were not based on animal welfare considerations only, but also other aspects, such as food safety, meat quality, environmental aspects and socio-economic aspects were taken into account. This is understandable, but creates a gap between explicit and implicit values, which we argue, can be overcome if such considerations are made more transparent to the citizens/consumers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Increased Focus on Animal Welfare

Since the early 1970’s, when the general public became more aware of developments in animal husbandry, there has been an on-going public debate about animal welfare issues (Harrison 1964; Blokhuis 2004). This long-term tendency of growing concern for animal welfare seems to be associated with changes in modern animal production and also with even more basic changes in the relationship between humans and animals (Roex and Miele 2005). These concerns, however, seem to be framed in very different ways in various countries (Roex and Miele 2005). According to the ‘Eurobarometer’ (European Commission 2007) a majority of European citizens think that it is important to protect the welfare of farm animals, and 77 % believe that there is a need for further improvement in the protection of farm animals in their country. The focus on animal welfare and the intention that animals should be properly cared for are also reflected by increased political activity within the EU (Bonafos et al. 2010), and growth in commercial initiatives led by farmer cooperatives and/or retailers and processors (Kjaernes et al. 2007).

It is not only the concern for animal welfare that has increased; the number of attempts to define the concept of ‘animal welfare’ is also increasing (Stafleu et al. 1996; Fraser et al. 1997; Bayvel and Cross 2010; Veissier et al. 2011). Due to different definitions of animal welfare there can be conflicting conclusions about how the animals should be treated (Fraser et al. 1997; Yeates 2011), and different approaches in selecting welfare criteria (Barnard and Hurst 1996). The fact that there is no full consensus today on how to define and measure animal welfare has not prevented the development of animal welfare legislation and standards in different countries (Barnett 2007).

The Development of Standards and Legislation within Europe

In this paper the word legislation refers to state based regulatory systems that are legally binding, and the word standard refers to all other kinds of regulatory systems, often private, like assurance schemes, programmes, policies, certification schemes, voluntary codes of practice or conduct etc. We use the term regulations to cover both legislation and standards.

According to Vapnek and Chapman (2010) the first legislation prohibiting cruelty against animals was passed in the English Parliament in 1822. This type of legislation which criminalizes cruelty against animals is still today the most common form of animal welfare legislation around the world. From early to mid-twentieth century a number of countries developed legislation about the prevention of cruelty and unnecessary suffering. The first national legislation of this kind was developed in England 1911, after which for example Denmark followed in 1916, Germany in 1933, Norway in 1935 and Sweden in 1944.

An important event for the animal welfare movement was the publication of Ruth Harrison’s book Animal Machines in 1964. In this book Harrison described some realities of intensive farming. As a reaction to this book the English Parliament requested that the Brambell Committee to examine the critique of modern farming methods and define animal welfare (Radford 2001). The Brambell report gave both a definition of animal welfare and the first suggestions to the Five Freedoms, which since then have been modified by the Farm Animal Welfare Council to what they are today; e.g. freedom from hunger and thirst, freedom from discomfort, freedom from pain, injury and disease, freedom to express normal behaviour and freedom from fear and distress. The Five Freedoms have been adopted and incorporated both in various national legislation and in EU legislation (Vapnek and Chapman 2010), even if they are not directly mentioned in legislative texts (Brown 2013). Due to increased focus on positive welfare (Boissy et al. 2007; Yeates and Main 2008; Wathes 2010) the next step in the development of legislation of animals kept by humans seems to be a movement from the protection of animals from unnecessary suffering towards giving the animals a quality of life that is worth living (FAWC 2009).

Today, farmers within animal production do not only have the governmental animal welfare legislation to comply with, but can in addition to this chose to certify their production according to different kinds of private standards (Fraser 2006; Aerts 2007; Ransom 2007; Veissier et al. 2008). There are at least 67 animal welfare standards within the EU, out of approximately 440 within the food safety area (Areté 2010). Most of these standards have been established during the last decades (Bayvel 2004; Fraser 2006; Ransom 2007; European Commission 2010). Due to this rapid development the European Commission has recently made best practice guidelines for standards (European Commission 2010), and in the Action Plan of the European Commission 2006–2010 on animal welfare there was a vision of a market approach (Heerwagen 2010), in which the responsibilities shift from state administration and national ministries to the market place and the consumers (Asdal 2006), a development that is not unique for the agricultural and food safety area (Webb and Clarke 2004). According to Cohen (2004) there is an evolution of regulation towards private rather than public institutions as well as a change from the twentieth century perception of government, which focuses on state institutions and instruments, towards a more nuanced notion of governance that is broad enough to allow activities of both state and non-state institutions and actors.

The private standards have been initiated by different stakeholders in the food chain, for example the processing industry (slaughterhouses and dairy plants), the industry organisations (farmer organisations, organic farming organisations), retailer organisations, governmental and non-governmental organisations (Veissier et al. 2008). The reasons for initiating standards and their purpose can be diverse (Butterworth and Kjaernes 2007), and the reasons why farmers choose to participate can also vary. Bock and van Huik (2007) saw that the main incentive for farmers to participate in any standard was to get higher prices for their products and better access to the market, but the farmers affiliated to an organic standard or to a specific animal welfare standard were mainly motivated by ethical concerns and the possibility to improve animal welfare.

The Importance of Ethics and Values in Decision- and Policy-Making

Animal welfare consists of several dimensions: scientific, ethical, economic, and political (Lund et al. 2006; Christensen et al. 2012). If relevant, rational and reliable answers concerning animal welfare are to be made possible, there must be an interdisciplinary approach involving philosophic reflections and theoretical biology (Sandøe and Simonsen 1992; Yeates et al. 2011). Sociological, economic, and ethical aspects must be taken into consideration to make it possible to actually implement new findings about animal welfare in policies (Appleby 2004; Yeates et al. 2011). It is often expected that animal science alone can provide all the answers as to what animal welfare is and whether or not the welfare of an individual animal is good, but there are reasons to question this (de Greef et al. 2006). There are also strong reasons to question if science alone can and should be setting the minimum level of acceptable animal welfare in legislation and standards. The issue of what is a minimum acceptable level of animal welfare is an ethical rather than a scientific question, because at the end some judgements have to be made (Lundmark et al. 2013). These can, however, of course be based on scientific information.

Previous research concludes that when it comes to what ethical views (i.e. systematize what is a right or wrong action) animal welfare legislation is based upon, the utilitarian view is the most frequently used, even if deontological ethics can be perceived (Sandøe et al. 2003; Würbel 2009). When it comes to values (i.e. what is important/what is of a value for people (stakeholders) as a motive or goal) some research has been carried out about values in organic production, for example within the EU project Organic Revision (Padel et al. 2007a, b, 2009). However, not only organic, but all kind of animal welfare legislation and standards are based on a set values and premises, and to the best of the authors’ knowledge there is very little research in this area. In this paper we therefore intend to investigate the value basis of some national legislation and standards where animal welfare is said to be in focus, in order to contribute to the discussion about animal welfare, policymaking and values.

Aims of this Study

The first aim of this paper is to describe the intentions and values that can be found in 14 animal welfare legislations and standards in four European countries; Sweden, United Kingdom, Germany and Spain. A second aim is to discuss if the legislation and standards actually accomplish what they, in their overall description and ethics, claim to do, i.e. if the intentions are followed up by relevant paragraphs in the actual body of the text in the legislation and standards respectively. An overarching aim is to investigate to what extent these regulations may contribute to a higher level of animal welfare. This paper aims at providing an overview of the issues in question, not to give a full ethical analysis.

Materials and Methods

On-Line Questionnaire

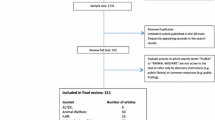

A questionnaire developed and used in the research project EconWelfare (‘Good animal welfare in a socio-economic context’), www.econwelfare.eu, was partly used (Kilchsperger et al. 2010; Schmid and Kilchsperger 2010a, b). This questionnaire asked for information about different public and private initiatives for improved animal welfare.Footnote 1 The questions were related to objectives, main actors, main instruments used as well as to their implementation, evaluation and impact of each of the initiative. Information was collected from eight European countries. The animal welfare researchers in each country were responsible for selecting initiatives according to specific criteria that were set up by the Econ Welfare group (Kilchsperger et al. 2010). To create a manageable corpus we selected four countries (out of eight countries) which had previously been shown to have different approaches and attitudes to animal welfare (Keeling et al. 2012). The animal welfare legislation from these countries was chosen together with 10 private standards. The countries and regulations are shown in Table 1. It should be mentioned that there are many other standards in the chosen countries, with a higher proportion of participating farms, which were not covered by EconWelfare and therefore not included here. It is also worth mentioning that there were differences between the standards as to how voluntary the farmers’ participating really was, in terms of market mechanisms etc.

The legislation and standards differed in relation to what animal species and categories of animals they covered. The private standards chosen in this study concerned one or several species of farm animals. The pieces of legislation included not only animals kept for farming purposes, but also other species kept by humans and sometimes even wildlife and invertebrates (Lundmark et al. 2013).

Text Analyses

In addition to these questionnaires, we made text analyses on the actual regulations and on the information available about them; including preparatory work, explanatory notes, web pages and brochures. To limit the scope of the national legislation the Animal Welfare Acts and the regulations on the housing and management of farm animals were analysed. The standard from Marks and Spencer could be analysed from the basis of the summarized information on the web page only, as the company refused to provide us with the actual standard in spite of repeated efforts.

A pilot study was made to make a first attempt to identify ethical values within animal welfare legislation (in the UK, Spain, and Argentina) and evaluate the method for text analyses (Behdadi 2012). The analysis used was argument analysis, including a concept analysis and value theory. In an argument analysis, explicitly and implicitly expressed premises (arguments) are searched for in relation to a specific conclusion or statement, e.g. what arguments, open or hidden, are used to draw a certain conclusion or make a statement (Feldman 1999). During the argument analysis common concepts were noted. The arguments used were scrutinized in order to establish whether they were built on facts (for example scientific research or long experience) or a value, or both.

Based on the pilot study and first text analysis of this study a total of seven focus areas were identified and described in a scheme structure. These focus areas had emerged in all, or the majority, of the regulations and were areas where similarities and differences in values could be discovered. The focus areas were; intentions with the legislation/standard, the concept of animal welfare, the five freedoms animal welfare concept, unnecessary suffering, natural behaviour, the stock-keeper´s role and the killing of animals, which is reflected in the presentation of the results below.

Results

The following results are based on the EconWelfare questionnaires as well as the EconWelfare analysis reports (Kilchsperger et al. 2010; Schmid and Kilchsperger 2010b) and our interpretation of these, and our analyses of standards and legislation in Sweden, the UK, Spain and Germany. We have chosen to present the results from the questionnaires of specific relevance to the research question about values and intentions in this study based both on explicit statements and implicit values in the regulations analysed.

The Initiators and Owners Behind the Legislation and Standards

The initiators/owners of the initiatives represented different parts of society. Whereas the legislation was of course a product of the governments in each country, the private standards were of more varied origin. Swedish Seal of Quality, Arlagården, the Laying Hen Welfare Programme and the Broiler Welfare Programme were all industry initiatives. M&S was a retailer initiative, KRAV and Neuland were farmer initiatives and Soil Association was initiated by farmers together with scientists and nutritionists. Freedom Food was initiated by an animal interest group. However, several of the initiatives had more than one initiator, in some cases representing completely different stakeholder groups. The main initiators/owners of the standards are presented in Table 1. When developing and updating the regulations most of the initiators/owners seem to have involved external experts and stakeholders in the process; for example scientists, farmers, authorities, consumer associations and animal welfare organizations.

The Intentions Behind the Legislation and Standards

The ideas behind different sets of legislation and standards have arisen under different circumstances. Even if all of the initiators/owners had incorporated animal welfare in their regulations a majority had also other areas and circumstances to consider. This means that animal welfare was not necessarily the main driver in the development process of all standards included in this study.

Public Concern and Consumer Influence

The present legislation in e.g. Sweden and UK were written mainly because of public concern about animal welfare, the negative impacts of intensification of food production and new knowledge, whereas the present legislation in Spain mainly exists as a result of demands from the European Union. For the private standards welfare scandals in the media, public or consumer concern, widespread animal diseases and the need for a trustworthy labelling were some of the reasons to initiate the standards. Looking at the basis of the claims the majority of industry, retailer and farmer initiated standards had taken consumers´ attitudes into account, beside other factors that also the legislators had considered, such as animal behaviour, animal health and ethical considerations. Arlagården very clearly stated that they are focusing on what the consumers expect; ‘All of our rules that are based on national legislation have been included in this standard because they regulate conditions that are of special importance to customers and consumers’ (our translation) (Arla 2011, p. 5). Seal of Quality motivated the requirement to give dairy cows access to pasture in line with the consumers´ demand and expectations. Several of the private standards also had the producers in mind when claiming that the standard in question would result in high quality products resulting in better prices for the producers.

Comparing Focus Areas in the Regulations

The majority of the private standards also had other focus areas than animal welfare, although the emphasis on animal welfare was strong. These other focus areas were for example food safety, disease control, environmental protection, milk composition, food quality, conservation of rural or peasant agriculture, regionalism, fair prices and stopping rural depopulation. The only private standard that focused solely on animal welfare was Freedom Food; but also a few other standards had a heavy focus on animal welfare. The countries’ animal welfare legislation texts were also focused on animal welfare only, but the initiators (e.g. responsible governments and agencies) mandate descriptions also involved focus areas other than just animal welfare; for example ensuring a strong and competitive agricultural sector, food safety and environmental protection. So even if a specific piece of legislation covered animal welfare only, the initiator had several other areas to take into consideration; areas that were also shared by a majority of the industry and farmer initiated initiatives. Even RSPCA (Freedom Food), which only focused on animal welfare, had taken other interests into consideration when developing the welfare standards as illustrated by the quote; ‘the standards are set at the limit of what is achievable, in terms of an animal husbandry and commercial viability…’(RSPCA 2012). Also KRAV showed an awareness of their standards having to function in a broader context, limiting what is acceptable or realistic; ‘The standard is set according to what is practically achievable at this present point in time’ (our translation) (KRAV 2012, p. 32). In the code of recommendations (for the welfare of livestock) to the UK Animal Welfare Act it said that the five freedoms form a logical basis for assessing animal welfare but within ‘the limitations of an efficient livestock industry’ (Defra 2012, p. 3). In the bill to the Swedish animal welfare Act it was made clear that economic considerations had been important; both when it comes to the animal welfare level requested and also regarding how rapidly new requirements would enter into force.

Animal Health and Welfare

The majority of the regulations described an overall aim to improve animal health and welfare. Natural behaviour (or similar expressions) and good husbandry were often mentioned as objectives as well as absence from suffering (the specific word ‘suffering’, however, was mainly mentioned in the legislation). KRAV also mentioned that animals should be treated with dignity and Swedish Seal of Quality used the phrase ‘animals should be respected as sentient beings’ (our translation) (Swedish Seal of Quality 2011), a phrase that is similar to the statement in Article 13 in the Lisbon Treaty (European Commission 2008). For Carnes Valles del Esla the main aim concerning the animals was to have an extensive type of production, for the benefit of animal welfare. The German Animal Welfare Act had a slightly different aim than the others as the first paragraph states that not only the well-being but also the lives of the animals should be protected; ‘The aim of this Act is to protect the lives and well-being of animals…’ (Tierschutzgesetz 1972, §1).

Synergetic Effects and Goal Conflicts

We found a risk for goal conflicts between different areas; for example between food safety, meat quality, environmental aspects and animal welfare, when these areas were covered by the same standard. For example the organic standard of Soil Association, and to some extent KRAV, did not approve the use of synthetic substances, such as synthetic amino acids, although these might be beneficial or sometimes even necessary for animal health and welfare. However, we also saw that regulations for different areas could have some synergetic effects. The goal of a quality product can, for example, be positive for the welfare of the animals when it comes to demands for healthy udders in dairy cows and clean animals in general. Our interpretation is actually that the main goal conflicts existed within the same area, in this case animal welfare, where the intentions of and values behind the regulations could be questioned in relation to the subsequent and more specific paragraphs. Several pieces of legislation and standards stated that animals should be protected from suffering and treated well, but nevertheless allowed painful procedures, for example castration without anaesthetics. Many standards expressed for example an intention to let the animals live a life were they can behave naturally. One example of this is the standard of KRAV, which mentioned the importance for mother and young to have the opportunity of close contact in the initial period of life of the offspring, but still accepted removing the calf from the dam at 24 h after birth (other standards accepted calf removal immediately after birth). Furthermore, an intrinsic conflict in farming for food became evident in the German animal welfare act, holding the aim to protect the lives of animals, although slaughter of young and healthy animals for meat consumption is allowed.

The Concept of Animal Welfare and the Five Freedoms

Besides the concept animal welfare, concepts like animal protection, animal well-being, animal health, animal fitness, animal care and animal friendly were used in the legislation and standards or in connection to them. Furthermore, the Swedish Broiler Welfare Programme used another concept to explain how the animals should be treated; animals shall be treated in a ‘correct way from an animal ethics point of view’ (our translation) (Svensk Fågel 2011). What exactly the different stakeholders refer to, however, was in general rather vague. It is likely that they sometimes meant the same thing but used different words or terms. It could also be the other way around; that they used the same words or expressions but actually did not mean the same thing. Apparently, most of them thought that it was essential for the animals to be healthy, to have physiological and behavioural needs fulfilled and not suffer unnecessarily. Some emphasized that they meant both physical and mental health and some emphasized that the measurement to ensure animal welfare must be of a preventative nature. Carnes Valles del Esla, Neuland and the two organic standards (Soil Association and KRAV), were focusing more explicitly on natural behaviour than the others. Freedom Food, Soil Association and Neuland clearly stated that they are striving for a positive animal welfare.

In the UK the concept of the five freedoms was often used as a base for a standard or legislation on animal welfare, which was not surprising, as the concept was originally developed by a UK group of scientists. This concept was also used in connection with the Spanish legislation. However, all countries studied have somehow included the content of the five freedoms even if they did not all use the specific term ‘five freedoms’. This was an expected result since also the EU legislation is partly based on the concept of the five freedoms.

(Un)necessary Suffering

The prevention of animal suffering was a central concept in the national legislation of all the four countries. The suffering that should be prevented was the one that is ‘unnecessary’ (Sweden, UK and Spain) or ‘avoidable’ and that is ‘caused without a good reason’ (Germany). Logically there is suffering that is necessary or unavoidable and therefor legal to expose animals to (Lundmark et al. 2013). Our interpretation is that the private standards also strive to prevent suffering but they consistently used other terms than ‘suffering’. The two organic standards more often used ‘stress’; focusing on minimizing the stress affecting the animals. Freedom Food stated that they wanted to protect the animals from ‘distress, discomfort or fear’. In some of the legislation/standards it was clarified that both physical and mental suffering was included.

Not much information was to be found about what (un)necessary or (un)avoidable suffering is, where to draw the line when it comes to minimizing stress or when there is a good reason to cause an animal suffering. The UK animal welfare act was the only regulation that actually gave some guidance in the legislative text. In section 4 (3) there is a list of considerations that should guide the courts when determining whether suffering has been unnecessary or not. The ‘considerations focus on the necessity, proportionality, humanity and competence of the conduct’ (Explanatory Notes 2006). In the government bill (1987/88:93) to the Swedish animal welfare act it is said that it is sometimes unavoidable to cause animal suffering and that this kind of suffering should be seen as legal. Two example are mentioned; the treatment of sick animals and the use of animals for scientific purposes; i.e. research on animals. Neuland favour small and medium-sized farms, since ‘mass raising’ of animals causes animals to suffer when these animals are treated like ‘means and not like ends’, implying that large-scale farming inherently leads to unnecessary suffering.

It was clear that different initiators made different assessments as to whether an action or situation results in a suffering for the animals or not, and that they had different views on what kind of suffering that was considered unnecessary and could be avoided. The regulations allowed and forbid different actions/situations. The differences could be seen on four levels; (1) between countries, (2) between different regulations within a country, (3) between different species of animals covered by the same legislation/standard and (4) between individuals of the same species covered by a regulation (e.g. different procedures allowed for different ages and different rules depending on the purpose of the keeping of the animal; production, companion, zoo etc.).

The Stock-Keeper’s Role

All initiators mentioned, in one way or another that the animal owner or the stock-keeper has a responsibility to fulfill the regulations and take proper care of the animals, but how much focus the stock-keeper was given differed. The majority of initiators stated that the stock-person should be competent, skilled, experienced, etc. While some initiators more or less just stated that the stock-keeper has a responsibility for the animals, others tried to describe the ideal stock-person in words. For example compassionate (Freedom Food), treating the animals with respect (Swedish Seal of Quality and the Broiler Programme), relaxed (Soil Association) and total awareness regarding the needs of animals (Carnes Valles del Esla). In the UK code of recommendations and Freedom Food whole chapters were regulating the stock-keepers duties and responsibilities. Soil Association had another approach in showing the importance of the stock-keeper by directing all the rules to the human; ‘you must’, ‘you need’, ‘you should’, ‘your animals need to be provided with’ etc. Other legislation/standards regulated the outcome from the animals perspective; for example Arlagården and the Swedish animal welfare legislation wrote; ‘animals must’, ‘animals must not’, ‘all animals shall’, ‘the animals are entitled to be provided with’ etc.

The extent to which the initiators mentioned why the stock-keepers have an important role for the animals’ welfare and a duty to fulfill the regulation varied. Some (more or less) just mentioned that it is ‘obvious’ that the owner or stock-person is responsible for treating the animals well; this was the case for example in the Swedish legislation and in Arlagården. In the recommendations to UK legislation it was stated that ‘Without good stockmanship, animal welfare can never be properly protected’ (Defra 2012, p. 3). Others specified that it was a ‘moral duty’ to treat the animals well; for example Swedish Seal of Quality and Carnes Valles del Esla. Carnes Valles del Esla had also an economic argument as to why animals must not be abused: ‘a complete rejection concerning animal abuse, as it is neither morally nor economically justifiable’ (our translation) (Valles del Esla 2012). M&S mentioned the argument that ‘We maintain our high quality food range due to the high standards of our farmers’ (M&S 2012); i.e. good stockmanship is necessary for good meat, milk and egg quality and of importance to make the consumers confident that the animals have had a good life (so that the consumers can eat with a good conscience). Soil Association also mentioned that it is good to treat the animals calmly for meat quality reasons. Some initiators; for example KRAV and Soil Association, mentioned that a calm and good treatment of animals minimizes the stress of the animals, which is a prerequisite for healthy animals. The German legislation stated that humans must protect the animals because they are ‘fellow creatures’. According to RSPCA (Freedom Food) stock-keeping should be carried out in a compassionate way because if you treat your animals well this will probably mean that you also treat humans compassionately. RSPCA’s mission is ‘to promote compassion for all creatures’.

Natural Behaviour

A majority of initiators claimed that they had a goal to adjust the environment to suit the animals and not the other way around. All of the initiators behind the legislation and standards mentioned that the animals’ natural behaviour must be taken into considerations. Slightly different expressions were used besides natural behaviour; for example species-specific behaviour, the specific identity/quality and specific needs, natural or near-natural lifestyles, biological and behavioural needs and normal behaviour patterns, in this text subsumed to ‘natural behaviour’. There was, however, a slight difference in how the concept was used. Some of the initiatives had a requirement that animals must be given the opportunity to perform natural behavior (or a similar concept) directly in the regulation, for example the legislation of Sweden, Germany and UK and the two organic standards. Others did not explicitly use the concept of natural behaviour in the legislative text but instead, for example, in preambles or introductory texts to the standards, implying that farmer compliance with the rules is a prerequisite for the animals to behave naturally. This was the case for example in Arlagården, Swedish Seal of Quality, the Broiler Welfare Programme and Carnes Valles del Esla. One standard did not mention it at all but referred to the national legislation that has natural behaviour as one of the most important keystones.

Generally, the initiators very rarely gave explanations to what they meant, more precisely, with expressions that imply that an animal, according to their regulation, should be given the opportunity to perform natural behaviours. In Freedom Food there was a list of abnormal behaviours and it was stated that measures must be taken if any of these are shown. Neuland emphasised on the animal’s possibilities to be free-ranging outdoors. Our interpretation is that Carnes Valles del Esla was taking this one step further; striving for the animals to live a ‘natural’ life, i.e. as close to a life in the wild as possible, as they mentioned pastoralism and the naturalness of this husbandry system as benefits. In the government bill to the Swedish animal welfare act a hesitant attitude was shown to modern and large stables or sheds when it comes to the animal’s abilities to perform natural behaviours. However, what natural behaviours the Swedish legislators actually wanted to support remains unclear.

Killing of Animals: Death is not a Welfare Problem in Itself?

All of the studied pieces of legislation and most of the private standards had requirements related to killing of animals, mainly about slaughter of animals for meat production, stating that such slaughter must be humane. Carnes Valles del Esla stressed that the slaughter method is important not only for the sake of the animals but also for the meat quality. However, the majority of regulations also considered killing of animals to be a method of preventing further suffering, i.e. euthanasia. In the UK legislation it was claimed that it can be beneficial to an animal to be killed or destroyed; ‘If a veterinary surgeon certifies that the condition of a protected animal is such that it should in its own interest be destroyed…’ [UK Animal Welfare Act 2006, 18(3)]. Although, for animals participating in prearranged animal fights it was not only the interest of the animals that mattered, but also public safety. The initiators very rarely discussed or questioned the right of humans to kill animals. Implicitly it was clear that all initiators behind these legislation texts and standards accepted the tradition or convention to kill animals for meat. However, for animals which have not yet reached the planned slaughter weight or were not at all intended for slaughter there were some alternative patterns of reasoning. For example, the Soil Association and Freedom Food discouraged the killing of healthy newborn calves. No initiators were comfortable with killing animals for other purposes than meat or prevention of suffering; RSPCA for example was opposed to the killing of animals ‘in the name of sport, entertainment or fashion’. In the Swedish bill to the legislation it was stated that if animals are sick or injured; killing must be the last remedy. At the same time there was no ban against killing perfectly healthy animals in Sweden since animals were seen as someone’s property (Striwing 1998). The situation is slightly different in Germany where animals since 1990 are no longer considered ‘things’ in the German legislation, although it has been doubtful whether this change has more than a symbolic meaning (Benz-Schwarzburg 2012). However, in the German state North-Rhine Westphalia a ban on the killing of one-day old male chickens has recently been adopted, within the laying hens industry, claiming that this killing is unnecessary and not in line with the intentions of the German legislation (The Local 2013).

Even if the sudden death of an animal can be seen as a way of preventing further suffering, and therefor favourable for the welfare of the individual animal, the herd or flock mortality on farm level was sometimes used as an animal welfare assessment parameter, for example by the Swedish Seal of Quality and the Laying Hen Programme. Too high mortality on a farm could obviously be seen as a welfare problem, probably because it indicates problems related to the health or management of the animals, imposing suffering prior to death.

Discussion

This discussion is focused on the sections of the results that we have found most interesting with regard to the aims of our study, i.e. in relation to the intentions and values stated in the studied documents.

The Focus is not Only on the Animals

From this study it is clear that the animal welfare legislation and these standards were not only taking the animals into concern, but that several other factors, i.e. economy, culture, traditions, religion, consumer demands, environment, food quality, food safety, disease risks etc., were also taken into account when an acceptable welfare level was decided upon. Other studies have also shown that it is not science alone that has an impact on the requested welfare level (Sandøe et al. 2004; Croney and Millman 2007). On the contrary, the chosen level depends on the intentions and values behind a legislation or a standard. Many of the private standards were clear on the fact that consumer demands and producers interests matters when setting the standards, and since such interests often relate to animal welfare such aspects have a central role in the standards. In animal welfare legislation, it was not made clear what other aspects were found to be relevant or why certain animal welfare levels were chosen, but reading the available mandates of the legislators lead us to the non-controversial conclusion that they must also have taken into consideration other interests than animal welfare alone.

Values and Ethical Views will Differ

We found that the legislation and standards used different concepts besides ‘animal welfare’. The precise meaning of these concepts remained unclear although some clues were given as to what was assumed to be important to the animals. Numerous studies have been carried out on different stakeholders’ and citizens’ attitudes to, and perception of, animal welfare. Van Poucke et al. (2006) saw a difference in the perception of the current state of animal welfare between men and women and between people from town or countryside in Belgium. Men perceived the current animal welfare state as being better, as did the people from rural areas. Boogaard et al. (2006) showed that considerations and definitions of animal welfare could differ depending on what experience a person has of animals. Pet owners were more negative to the welfare of farm animals than people without a pet, and people with farm experience perceived animal welfare more positively than people without this experience. Within the Welfare Quality® project a difference between consumers and animal welfare scientist was identified (Miele and Evans 2006). Consumers had more holistic concerns wanting the animals to experience positive emotions and have ‘natural’ living conditions, while scientists were more quantitative, more goal oriented and characterised primarily animal welfare by the absence of suffering. Also Bracke et al. (2005) describe that scientists were affected by the need to measure welfare with quantifiable parameters and that consumers had pictures of traditional farming and animals’ natural environment in mind, while producers perceived welfare from a production point of view. In a recent study indications were given that if the perspectives of what good animal welfare is differed between the farmer and the government (legislators and animal welfare inspectors) this could lead to implementation problems (Andrade and Anneberg 2014). Even if differences have been shown between different groups of stakeholders there are also common views. Aerts and Lips (2006) saw shared views by consumers, producers, other economic actors, scientists, government officials and NGO’s; economic welfare, care, respect and taking responsibility, although, not all values were equally important to all.

Differences exist not only between stakeholder groups but also between individuals and sub-groups within a given stakeholder group. De Rooij et al. (2010) discovered different views between farmers (on an individual level) such as; meeting legislative minimum requirements, good health and good production levels, abilities to express natural behaviour and respect for the animals intrinsic value. Bock and van Huik (2007) saw that organic pig farmers valued the animals’ opportunity for expressing natural behaviour highly, while conventional farmers defined animal welfare in terms of animal health and production performance.

Lund et al. (2004a) concluded that natural behaviour was a central aim when defining animal welfare in organic production, but natural behaviour was more important to the pioneers (who saw organic farming as a lifestyle) than to the entrepreneurs (who saw organic production as a way of making money and meet new challenges). Hubbard and Scott (2011) noticed that UK-farmers affiliated to Freedom Food (besides organic standards) associated animal welfare with the possibility to express normal behaviour to a larger extent than UK-farmers affiliated to other standards did. It is apparent that people’s values differ between cultures and individuals and these values will affect how animal welfare is understood (Vapnek and Chapman 2010). Sandøe et al. (2004) pointed out that concepts like ‘animal welfare’, ‘stress’ and ‘suffering’ are value-laden concepts in themselves and even within the scientific community there will be different understandings. These differences could for example mean that one person believes that a free-range organic hen has a better welfare as a result of the possibility to behave naturally outside, while another person focuses on health and think that the welfare is poorer on an organic farm due to the risk of parasites (Sandøe et al. 2004). Bilchitz (2012) mentioned that one key problem with legislation is when it contains a number of vague concepts that are poorly defined. Based on both our study and the results mentioned above, it is quite obvious that policy makers cannot take for granted that what they consider as animal welfare is interpreted in the same way by others, including producers and consumers. If there are different understandings of concepts used in the regulations there is a risk that the interpretations will differ when discussing what is actually acceptable according to a certain standard or legislation, or not.

Furthermore, the stock-keepers role will differ depending on both their own understanding of animal welfare, but also likely depending on what the policy maker focuses on in relation to ‘animal welfare’. If the animals’ health is stated in a standard or legislation to be central this is probably what the stock-keeper will focus on; if an extensive production is central this is probably what the stock-keeper is supposed to focus on and make it work. Furthermore, Sandøe et al. (2003) pointed out that legislation is made from different point of views and cover different and often conflicting concerns with the purpose to provide a minimum standard. Animal welfare legislation is mainly based on an utilitarian view, even if deontological ethics also can be perceived (Sandøe et al. 2003; Würbel 2009). We would like to argue that it is likely that at least partly other ethical views can be found mainly behind the private standards. Since industry and retailer standards are often concerned about the consumer and producer interests it is quite possible that a contractarian (Rawls 1971; Lund et al. 2004b) view might have some influence on formulation of standards (Lundmark et al. 2013). We also suggest that the compassionate stock-keeper in Freedom Food is an example of expressing ideals, which come close to a virtue ethics (Nussbaum 2006; Anthony et al. 2013) approach.

In the EU project Organic Revision core values and their relation to each other in organic production have been investigated (Padel et al. 2007a, b, 2009) based on the four different core values distinguished by IFOAM, the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements; health, ecology, fairness and care (Padel et al. 2007a). Health including also the animals’ health, fairness including the respect for other organisms and animal welfare; i.e. respect for physiological, natural behaviour (‘naturalness’) and well-being (Padel et al. 2007b). However, not only the organic standards are value-based. To a certain extent, all legislation and standards are influenced by values and this will affect what is acceptable or not and what is a ‘good enough’ welfare for the animals. We can conclude that all initiators agreed upon the view that humans have a right to use animals for our own good, i.e. that humans have a higher moral status than non-human animals. As this is a foundation for justifying human use of animals, it should be no surprising, but worth noting, that the basis for this starting point is not explicitly motivated. Rather, efforts are made in some legislation to indicate that animals and humans are not all that different in a biological sense. The German legislation, for example, indicates that animals are our fellow creatures and that they feel pain the same way that we do, leading to the conclusion that if there is a type of surgical procedure where humans do not need anaesthetics then the animals will not need it either. The UK legislation has clarified that in the Act ‘animal’ means a vertebrate other than man; i.e. also humans are animals. Interestingly, the UK legislators have felt an urge to clarify that human animals are not protected by the animal welfare act, while in the other countries this is taken for granted. In the Spanish legislation it is even explained that fish, reptiles and amphibians are animals (which is the same wording as in Council Directive 98/58/EC of 20 July 1998 concerning the protection of animals kept for farming purposes). Given these stated biological similarities and analogies, our interpretation is that the introductory paragraphs or texts about animal capacities and policy-maker intentions behind the regulation often indicate a more generous policy than actually formulated in the following, detailed requirements and the application of the legislation and standards.

Let the Animals Behave Naturally

One basic value found in both legislation and standards was that animals should be given the possibility to behave ‘naturally’. This was not unexpected since it is a common principle mentioned in relation to in animal welfare legislation (Brown 2013). However, in this study we have seen that it is not entirely clear what behaviours were considered as being ‘natural’ and apparently different values existed in relation to what was perceived as important when it comes to the animals possibilities to behave naturally. Segerdahl (2007) also argued that no consensus has been made concerning the definition of natural behaviour in relation to policymaking and legal documents. In this study different approaches to ‘natural behavior’ were discovered; from desiring animals to live as close to the wild situation as possible to accepting a confined indoor environment, as long as the animals can still perform some crucial behaviours in this housing system. Our interpretation is that even if it could sometimes seem as if the initiators want ‘natural behaviour’ to be perceived as a broad concept it was used as a rather narrow concept in the regulations. This concept mostly focused on the design of the animals’ husbandry system and environment, and less on social structures, weaning, feed, mutilations or mating behaviours. In 2011 a governmental commission in Sweden presented a suggestion for defining natural behavior in a future Swedish animal welfare act (SOU 2011:75): ‘the animals should be able to perform behaviors that a) they have a strong motivation to perform, b) that give a functional response, and c) that relates to the animals need of movement, rest, comfort, occupation, foraging and social relations’. However, this clarification has not yet been implemented and no new animal welfare act has yet been adopted.

Also in a limited sense it is probably strategically important to have ‘natural behaviour’ as a claim when trying to appeal to consumers and to satisfy citizen requirements. Lassen et al. (2006) showed that living a natural life is of importance for the lay persons in defining what good animal welfare is, while the absence of suffering and frustration are central in the expert (farmers, technicians, scientists) approach. To have a requirement for natural behaviour can also be seen as having a preventive approach; i.e. to prevent abnormal behaviours, frustration and suffering. Lidfors et al. (2005) draw the conclusion that even if there is no consensus on the concept ‘natural behaviour’ there is enough knowledge for giving science-based recommendations on housing systems to support essential animal behaviours. Hence it is possible both to build housing systems and formulate standards and legislation ensuring that basic behavioural needs are met. However, it is important to be aware that there is a discrepancy between farming systems labelled ‘natural’ and the animals’ total spectrum of natural behaviours.

Do not Let the Animals Suffer in Vain

Another basic value found in both legislation and standards were that animals should not be exposed to ‘unnecessary’ suffering. This was not unexpected either since this is a common principle in animal welfare legislation (Brown 2013). The exact phrase ‘unnecessary suffering’, however, was rarely used in the private standards in this study. There could be three reasons for this: (a) suffering is a negative value-laden word and hence it is avoided, (b) having higher ambitions with voluntary welfare programme, i.e. only preventing unnecessary suffering is a too low level of ambition, and (c) private standards often complement national legislation and therefore there is no need to repeat basic requirements and concepts.

When looking at procedures known to create a certain level of pain, distress or anxiety and therefore suffering for the animals, an interesting and inconsequent pattern emerges on what the regulations state as necessary or not. We will give you three illustrative examples; beak trimming, castration, and slaughter without prior stunning.

Beak trimming of laying hens is allowed in e.g. German and Spanish legislation but not by Neuland and not by any of the initiators in Sweden. It is known that beak trimming of poultry is painful and will cause acute pain in chicks and chronic pain when performed on older birds (Jendral and Robinson 2004; Gentle 2011). Beak trimming is also stressful (Jendral and Robinson 2004) and will prevent birds from exploring the environment and preening themselves (Duncan 2004). On the other hand, beak trimming can be seen as a way of improving animal welfare by decreasing the risk of feather pecking and cannibalism in layer flocks (Gentle 2011). In addition to causing injury and distress to the birds feather pecking and cannibalism can also result in economic losses for the producer (Weary and Fraser 2004). However, there are other methods of reducing possible negative welfare effects in non-beak trimmed layer flocks. Obviously, different regulations have valued these arguments differently when deciding on banning beak trimming or not.

Castration of male piglets is mainly done as a result of consumers’ demand for good meat quality since castration increases the deposit of fat (Prunier et al. 2006) and prevents the unpleasant boar-taint (Bonneau et al. 1992). Castration also makes the male animals’ behaviour easier to control (Prunier et al. 2006). Studies have shown that it is painful and stressful for the pigs to be castrated without anaesthetics at any age (EFSA 2004; FAWC 2011; Rault et al. 2011). Despite this it is allowed according to the legislation in the studied countries to castrate piglets before 7 days of age without anaesthetics, pain relief or veterinary involvement. While in Sweden it has, for example, previously been a norm to castrate (EFSA 2004)—although this is now being phased out—only 1–2 % of the male pigs in the UK are castrated, because of the tradition to slaughter the pigs at an earlier age (when boar-taint has not yet developed) and the fact that most of the pig producers (90 %) are affiliated to private standards that do not allow this procedure (FAWC 2011). Castration of piglets is not allowed at all by Soil Association and surgical castration has been banned by Freedom Food. Freedom Food could, however, permit immunocastration. According to the Neuland standard, the pigs must be under anaesthesia and pain relief if castrated.

Inconsequences could also been seen within a specific regulation. For example Soil Association did not allow the castration of piglets at any age or by any method, but they allowed the castration and tail docking of sheep and goats with rubber rings before 7 days of age. These procedures are also painful (Kent et al. 1998; Rault et al. 2011) but unlike the castration of piglets, which has no tradition in the UK, the castration and tail-docking of lambs with rubber rings has been practiced in the UK for decades (French et al. 1992) and are seen as a quick, easy and cheap procedures (Kent et al. 1998).

Slaughter of animals is another welfare issue regulated in all national legislation studied and in most of the standards. Cutting the throat of an animal without prior stunning will involve pain and distress for the animal until it is unconscious (von Holleben et al. 2010). Of the countries covered by this study, only Sweden has a total ban on slaughtering animals without stunning prior to bleeding. Slaughter without stunning is allowed (under some circumstances) in the other three countries’ legislation but banned in some of the standards, for example by Neuland. The legal background for allowing the slaughter of animals without prior stunning is related to religious traditions (von Holleben et al. 2010). According to the Lisbon Treaty animals shall be recognized as ‘sentient beings’ and full regard shall be paid by the member states to the welfare of animals, but exceptions are allowed when it comes to ‘religious rites, cultural traditions and regional heritage’ (European Commission 2008).

The examples above make it very clear that the weight given to the necessity of these procedures differ between countries, within countries and within the same regulation depending on the animal concerned. All stakeholders basically have access to the same scientific results but they have drawn different conclusions with respect to what is considered to be necessary or avoidable suffering, and therefor legal or acceptable to expose the animals to. Considerations related to economy, consumer demands, food quality, religion, culture and traditions play a large role when deciding if something is unnecessary or not. In agreement with this study, also Hurnik and Lehman (1982), Radford 2001, Wahlberg (2008), Forsberg (2011) and Bilchitz (2012) have noticed that what the policymakers actually define as ‘unnecessary’ or ‘necessary’ is usually not well explained. We are suggesting four different factors that will affect the interpretation of (un)necessary and (un)avoidable suffering in legislation and standards; (1) the intensity and duration of the suffering, (2) the intention behind an act that caused the suffering, (3) the fulfilment of human interests or (4) the weight given to animals’ interest. Whereas the first factor is empirically assessable, but still subject to judgment, the other three are entirely values based, and hence in need of interpretation to state level of acceptance in each case. In reality a combination of these factors is probably used, but how to prioritize and balance between these is dependent on the values of the policymakers or the people that have to interpret the regulation (Yeates et al. 2011). Worth mentioning is also the fact that there are different definitions of pain (Sandøe et al. 2004) and that different understandings exist as to which species are capable of suffering and therefore should be of moral concern for humans (Lund et al. 2007) and hence covered by legislation and standards.

Differences Between Intentions and Requirements

It was expected that values would differ between the regulations and countries, and as a consequence the level of welfare and what was established as acceptable and unacceptable suffering. However, the discrepancy between the level of animal welfare stated as acceptable and the reputed intentions within a regulation was somewhat more unexpected. When there was a contradiction between intentions and claims this also makes it harder to understand what the values behind really were. These contradictions were actually most obvious in national legislation and organic standards, maybe because there were more explicit intentions to compare with. Some of the other standards were more vague about their animal welfare intentions and more clear on the fact that also consumer and producer interest mattered, besides the animals. Previous studies have argued that there are risks for goal conflicts within organic farming (Alroe et al. 2001; Waiblinger et al. 2007; Vaarst and Alroe 2011), that the organic core values are not always implemented in national organic standards and that external economic pressure may lead to temptations to find solutions less coherent with agreed core values (Padel et al. 2007b). Scientists have seen a challenge in, or questioned if, it is possible for producers to live up to the core values when the organic production becomes more and more large-scaled and intensive (Verhoog and de Wit 2006; Kulö and Vramo 2007). Not much focus has been spent on contradictions and goal conflicts in other standards and legislation, but this study has shown that such contradictions are certainly present.

We believe that there is a risk that the credibility of a regulation is undermined if the distance between the expressed intentions and actual requirements is too large. Clarity and transparency are important so that citizens and consumers can trust the regulation. We argue that it is better to be clear about the level of welfare intended instead of trying to present intentions and values that the consumers would like to hear. The latter implies a risks to disappoint consumers when actually reading the detailed regulation, or seeing its implementation on farms. Algers (2011) discussed that if consumer and industry expectations of requirements for good animal welfare differ, this could increase the conflicts between the consumers and food industry. A further complication is that although all EU member states have to implement and conform to the EU legislation, their national legislation might be built upon values that differ from that of the European Union policymakers.

Strategies for Improving Animal Welfare

Some of the standards claimed that they were not only striving for animal welfare, but for a positive animal welfare. This, however, does not necessarily mean that the other pieces of legislation/standards do not strive for this because words such as welfare or well-being can either be interpreted as a neutral concept (describing the physical and mental status of the animal), or as a positive word in itself; that the animals are ‘faring well’. The idea of having a positive approach when measuring animal welfare, and to focus on the animal’s positive feelings (what an animal ‘likes’) is a rather novel idea (Yeates and Main 2008; Boissy et al. 2007). However, this positive approach seems like a logical development in man’s humane treatment of animals (Wathes 2010) since the most common concern for animal welfare has been centred upon negative concepts (Yeates and Main 2008).

The discussion about what the most appropriate approaches for a country is, when it comes to improving animal welfare, has been quite active. Different countries have different strategies to safeguard animal welfare and there is no single solution to promote animal welfare (Keeling et al. 2011; Ingenbleek et al. 2012). Sweden, for example, has a large trust in governmental legislation, which goes beyond the EU level, while the UK has a larger trust in the market forces, and because of this has developed more extensive private animal welfare standards (Keeling et al. 2011). It can be argued that the private standards are more cost-effective than a legislative approach, have a positive impact on animal welfare for those involved and have helped to address consumer concerns (Bayvel 2004). However, other researchers find that it may be too risky to trust only the market in improving animal welfare through standards, and that we need baseline legislation that is applicable to all animals (Bennett 1997; Aerts 2007), i.e. not only to those owned by the most motivated and successful farmers. Ingenbleek et al. (2012) argued that if the national baseline legislation is above EU level the national government should consider lowering the legislation level and instead trust the market to maintain or increase the welfare level through private standards. However, it can be questioned if the consumers are knowledgeable, prepared and willing to take on this responsibility, especially as consumers often appear to have little knowledge of how production animals are kept and managed at modern farms (te Velde et al. 2002; Algers 2011; Lusk and Norwood 2011). It is also possible that consumers generally expect production systems to be humane and fulfil animal welfare requirements, and it has been shown that European consumers are interested in animal welfare improvements compared to the current levels (European Commission 2007). Furthermore, it can be argued that the stricter national legislation in some member states is a useful tool to raise the animal welfare levels when revising EU legislation. We believe that this must be discussed further.

Other aspects that matters when deciding the national level of animal welfare is the consumers value conflicts between buying cheap food products and asking for higher animal welfare levels; i.e. the consumers’ willingness to pay for animal welfare (Bennett and Larson 1996; Bennett and Blaney 2003; Grethe 2007), and the farmers wish for freedom of action; i.e. the farmers’ possibility to decide over the own animals at the farm. The hypothetical risk of driving production abroad, to regions with less regulated and controlled farming practices, if the requirements differ too much between countries, which may lead to a deteriorated animal welfare situation in contrast to the desired improvements, is sometimes also mentioned. These aspects are, of course, important but will not be discussed further in this paper.

It can also be questioned if a decrease in the level of mandatory legislation will automatically lead to a higher welfare level due to voluntary commitments even in the long run. Our impression is that the farmers’ willingness to affiliate to private standards varies and is not always as high as it may seem, an observation that is supported by Kilchsperger et al. (2010). If the proportion of farmers affiliated is very high, the standard may in practice not be that voluntary; e.g. the producers do not have a possibility to stand outside if they want to be able to sell their product. Hubbard et al. (2007) discovered that some farmers perceive the schemes as a ‘necessary evil’, that the membership within a standard was an economic necessity rather than a choice.

Are producers already having a high level of animal welfare (e.g. above national legislation) more eager to affiliate voluntarily to a private standard? KilBride et al. (2012) discovered that farms affiliated to a private standard had a higher compliance with animal welfare legislation than non-affiliated farms. This is not in agreement with Main et al. (2003) who found that dairy farms affiliated to Freedom Food in some cases had less welfare problems but sometimes actually more, compared to non-affiliated farms. Based on our results we would conclude that both the legislation and standards have the intrinsic potential to contribute to a better welfare even if there are some goal conflicts. Ingenbleek et al. (2012) stated that it actually could be beneficial when a standard covers several issues, beside animal welfare, because consumers can get ‘tired’ of the focus on animal welfare only.

Even if there is certainly a potential to improve animal welfare by legislation and standards this must be further investigated by comparing the intentions and values with the actual control of the requirements and the level of compliance.

Conclusions

The implementation of legislation and standards is one way to ensure or improve the level of welfare for farm animals in a country. However, since values will differ so will also the animal welfare levels set up in the regulations, irrespective of a common scientific knowledge about how certain procedures or situations will affect the welfare of the animals. As a result of these variations in values, we cannot ask for universally agreed explanations or definitions of different concepts used in animal welfare regulations around the world. Nevertheless, there is a need to define different concepts used, such as ‘animal welfare’, ‘unnecessary suffering’ and ‘natural behaviour’ in order to minimize variations in possible interpretations, as this will affect implementation, at least within the same regulation.

Animal welfare is an important aspect of consumer consideration in Europe. Private animal welfare related standards are often designed to appeal to consumers while still needing to be commercially viable and possibly also taking other aspects into account, a combination that may open for diverging values versus actual requirements. The introductory paragraphs/preambles and intentions of a regulation are often more generous to the benefit of the animals than the following detailed requirements, and for the sake of transparency and trust there is a need to decrease this gap between the intentions and the actual requirements. In this study, we found that the same applies also to governmental legislation. The values behind such legislation are often more explicitly stated, while the actual requirements are still modified in relation to e.g. the producers’ monetary constraints, environmental and socio-economic aspects or food safety. Furthermore, this study shows that the ethical values behind a set of legislation or private standards are not always consistently implemented. Neither is it always possible to follow the thread between the intentions mentioned initially and the actual details of the legislation or standard.

This study illustrates the importance of well thought-through values when developing legislation and standards and the importance of consistency throughout both regulatory documents and the policy-making process, to create transparent systems.

Notes

A copy of the EconWelfare questionnaire form can be obtained on request from the main author of this paper.

References

Aerts, S. (2007). Animal welfare in assurance schemes: Benchmarking for progress. In W. Zollitsch, C. Winckler, S. Waiblinger, & A. Haslberger (Eds.), Sustainable food production and ethics (pp. 279–284). Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

Aerts, S., & Lips, D. (2006). Stakeholder’s attitudes to and engagement for animal welfare: To participation and cocreation. In M. Kaiser & M. Lien (Eds.), Ethics and the politics of food (pp. 500–505). Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

Algers, B. (2011). Animal welfare—recent developments in the field. CAB Reviews: Perspectives in Agriculture, Veterinary Science, Nutrition and Natural Resources, 6(010), 1–10.

Alroe, H. F., Vaarst, M., & Kristensen, E. S. (2001). Does organic farming face distinctive livestock welfare issues? A conceptual analysis. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 14(3), 275–299.

Andrade, S., & Anneberg, I. (2014). Farmers under pressure. Analysis of the social conditions of cases of animal neglect. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 27, 103–126.

Anthony, R., Gjerris, M., & Röcklinsberg, H. (2013). Fish welfare, environment and food security: A pragmatist virtue ethics approach. In H. Röcklinsberg & P. Sandin (Eds.), The ethics of consumption—the citizen, the market and the law (pp. 257–262). Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

Appleby, M. C. (2004). Science is not enough: How do we increase implementation? Animal Welfare, 13, S159–S162.

Areté-Research & Consulting in Economics. (2010). Inventory of certification schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs marketed in the EU Member States. http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/quality/certification/inventory/inventory-data-aggregations_en.pdf. Accessed 14 May 2013.

Arla. (2011). Kvalitetsprogrammet Arlagården, version 3.1 [Quality Assurance Programme Arlagården, version 3.1].

Asdal, K. (2006). Re-doing responsibilities: Re-doing the state politics of food and the political market-place. In M. Kaiser & M. Lien (Eds.), Ethics and the politics of food (pp. 393–397). Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

Barnard, C. J., & Hurst, J. L. (1996). Welfare by design: The natural selection of welfare criteria. Animal Welfare, 5(4), 405–433.

Barnett, J. L. (2007). Effects of confinement and research needs to underpin welfare standards. Journal of Veterinary Behavior-Clinical Applications and Research, 2(6), 213–218.

Bayvel, A. C. D. (2004). Science-based animal welfare standards: The international role of the Office International des Epizooties. Animal Welfare, 13, S163–S169.

Bayvel, A. C. D., & Cross, N. (2010). Animal welfare: A complex domestic and international public-policy issue-who are the key players? Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 37(1), 3–12.

Behdadi, D. (2012). The Compassionate Stock-keeper’ and other Virtous Ideals. Values and Definitions in the Animal Welfare Legislations of the United Kingdom, Spain and Argentina. Report 32. Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. Skara.

Bennett, R. M. (1997). Farm animal welfare and food policy. Food Policy, 22(4), 281–288.

Bennett, R. M., & Blaney, R. J. P. (2003). Estimating the benefits of farm animal welfare legislation using the contingent valuation method. Agricultural Economics, 29(1), 85–98.

Bennett, R., & Larson, D. (1996). Contingent valuation of the perceived benefits of farm animal welfare legislation: An exploratory survey. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 47(2), 224–235.

Benz-Schwarzburg, J. (2012). Verwandte im Geiste, Fremde im Recht: Sozio-kognitive Fähigkeiten bei Tieren und ihre Relevanz für Tierethik und Tierschutz. Erlangen: Harald Fischer Verlag.

Bilchitz, D. (2012). When is animal suffering ‘necessary’? Southern African Public Law, 27, 3–27.

Blokhuis, H. J. (2004). Recent developments in European and international welfare regulations. Worlds Poultry Science Journal, 60(4), 469–477.

Bock, B. B., & van Huik, M. M. (2007). Animal welfare: The attitudes and behaviour of European pig farmers. British Food Journal, 109(11), 931–944.

Boissy, A., Manteuffel, G., Jensen, M. B., Moe, R. O., Spruijt, B., Keeling, L. J., et al. (2007). Assessment of positive emotions in animals to improve their welfare. Physiology and Behaviour, 92, 375–397.

Bonafos, L., Simonin, D., & Gavinelli, A. (2010). Animal welfare: European legislation and future perspectives. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 37(1), 26–29.

Bonneau, M., Ledenmat, M., Vaudelet, J. C., Nunes, J. R. V., Mortensen, A. B., & Mortensen, H. P. (1992). Contributions of fat androstenone and skatole to boar taint. Sensory attributes of fat and pork meat. Livestock Production Science, 32(1), 63–80.

Boogaard, B. K., Oosting, S. J., & Bock, B. B. (2006). Importance of emotional experiences for societal perception of farm animal welfare: A quantitative study in the Netherlands. In M. Kaiser & M. Lien (Eds.), Ethics and the politics of food (pp. 512–517). Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

Bracke, M., Greef, K., & Hopster, H. (2005). Qualitative stakeholder analysis for the development of sustainable monitoring systems for farm animal welfare. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 18(1), 27–56.

Brown, C. (2013). Animal welfare: Emerging trends in legislation. Animal Welfare, 22(1), 137–139.

Butterworth, A. & Kjaernes, U. (2007). Exploration of strategies to implement welfare schemes. In I. Veissier, B. Forkman & B. Jones (Eds.), Assuring animal welfare: from societal concerns to implementation (pp. 37–46). Second Welfare Quality stakeholder conference, 3–4 May 2007, Berlin, Germany.

Christensen, T., Lawrence, A., Lund, M., Stott, A., & Sandoe, P. (2012). How can economists help to improve animal welfare? Animal Welfare, 21, 1–10.

Cohen, D. (2004). The role of the state in a privatized regulatory environment. In K. Webb (Ed.), Voluntary codes—private governance, the public interest and innovation (pp. 35–56). Ottawa: Carleton University.

Croney, C. C., & Millman, S. T. (2007). Board-invited review: The ethical and behavioral bases for farm animal welfare legislation. Journal of Animal Science, 85(2), 556–565.

de Greef, K. H., Stafleu, F., & de Lauwere, C. (2006). A simple value-distinction approach aids transparency in farm animal welfare debate. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 19(1), 57–66.

de Rooij, S. J. G., de Lauwere, C. C., & van der Ploeg, J. D. (2010). Entrapped in group solidarity? Animal welfare, the ethical positions of farmers and the difficult search for alternatives. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 12(4), 341–361.

Defra. (2012) [a copy required 2012, year of publication unknown]. Code of Recommendations for the Welfare of Livestock—Cattle. London: Defra Publications.

Duncan, I. J. H. (2004). Welfare problems of poultry. In G. J. Benson & B. E. Rollin (Eds.), The well-being of farm animals: Challenges and solutions (pp. 307–323). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

EFSA. (2004). Welfare aspects of castration of piglets: Scientific Report of the Scientific Panel for Animal Health and Welfare on a request from the Commission related to welfare aspects of the castration of Piglets. The EFSA Journal. http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/doc/91.pdf. Accessed 4 Oct 2012.

European Commission. (2007). Attitudes of citizens towards animal welfare. Brussels: Eurobarameter.

European Commission. (2008). Consolidated Version of The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (Lisbon Treaty). Official Journal of the European Union. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:C:2008:115:0047:0199:en:PDF. Accessed 1 July 2013.

European Commission. (2010). Commission Communication—EU best practice guidelines for voluntary certification schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs (2010/C 341/04).

Explanatory Notes (2006). www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2006/45/notes.

FAWC. (2009). Farm animal welfare in Great Britain: Past. London: Present and Future.

FAWC. (2011). Opinion on mutilations and environmental enrichment in piglets and growing pigs. London.

Feldman, R. (1999). Reason and argument. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Forsberg, E.-M. (2011). Inspiring respect for animals through the law? Current development in the norwegian animal welfare legislation. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 24(4), 351–366.

Fraser, D. (2006). Animal welfare assurance programs in food production: A framework for assessing the options. Animal Welfare, 15(2), 93–104.

Fraser, D., Weary, D. M., Pajor, E. A., & Milligan, B. N. (1997). A scientific conception of animal welfare that reflects ethical concerns. Animal Welfare, 6(3), 187–205.

French, N. P., Wall, R., Cripps, P. J., & Morgan, K. L. (1992). Prevalence, regional distribution and control of blowfly strike in England and Wales. Veterinary Record, 131(15), 337–342.

Gentle, M. J. (2011). Pain issues in poultry. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 135(3), 252–258.

Grethe, H. (2007). High animal welfare standards in the EU and international trade—How to prevent potential ‘low animal welfare havens’? Food Policy, 32(3), 315–333.

Harrison, R. (1964). Animal machines. London: Vincent Stuart.

Heerwagen, L. (2010). Animal welfare: Between governmental and individual responsibility. In R. Casabona (Ed.), Global food security: Ethical and legal challenges (pp. 337–341). Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

Hubbard, C., Bourlakis, M., & Garrod, G. (2007). Pig in the middle: Farmers and the delivery of farm animal welfare standards. British Food Journal, 109(11), 919–930.

Hubbard, C., & Scott, K. (2011). Do farmers and scientists differ in their understanding and assessment of farm animal welfare? Animal Welfare, 20(1), 79–87.

Hurnik, F., & Lehman, H. (1982). Unnecessary suffering—definition and evidence. International Journal for the Study of Animal Problems, 3(2), 131–137.

Ingenbleek, P. T. M., Immink, V. M., Spoolder, H. A. M., Bokma, M. H., & Keeling, L. J. (2012). EU animal welfare policy: Developing a comprehensive policy framework. Food Policy, 37, 690–699.

Jendral, M. J., & Robinson, F. E. (2004). Beak trimming in chickens: Historical, economical, physiological and welfare implications, and alternatives for preventing feather pecking and cannibalistic activity. Avian and Poultry Biology Reviews, 15(1), 9–23.

Keeling, L., Immink, V. M., Hubbard, C., Garrod, G., Edwards, S. A., & Ingenbleek, P. (2011). Final report on policy instruments and indicators following stakeholder meeting. Econ Welfare, D, 3, 4.

Keeling, L. J., Immink, V., Hubbard, C., Garrod, G., Edwards, S. A., & Ingenbleek, P. (2012). Designing animal welfare policies and monitoring progress. Animal Welfare, 21, 95–105.