Abstract

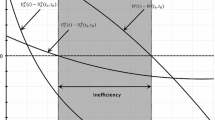

Inter-regional redistribution through tax-base equalization transfers is examined in a setting in which taxpayers, organized as lobby groups, influence policy making. With lobbying only at the local level on tax rates, social welfare maximization implies, ceteris paribus, high (low) equalization rates on the tax bases backed by the strong (weak) lobby groups. With lobbying also at the central level, equalization is distorted downward on all tax bases if the pressure groups are similar in terms of lobbying power. It is instead distorted downward (upward) on the bases backed by strong (weak) groups if they are highly heterogeneous. In the latter situation, a uniform equalization structure may perform better than a differentiated one.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The only exception is Canada, where all standard tax revenues are equalized at 100 % for the recipient provinces (those with below-average fiscal capacity), whereas actual revenues from natural resources are equalized at 50 %. The reason is that with full equalization the public authorities of the territories in which the resources are located would have no appropriate incentives for their development.

See Esteller-Moré et al. (2012) for anecdotal evidence of lobbying by the tobacco and oil industries in the USA to influence policy choices about excise taxes on the sale of their products.

The quasi-linearity assumption is made for analytical convenience and can be relaxed. For some types of production factors, the empirical estimates of the impact of income taxes on their supply find weak income effects (see, e.g., Gruber and Saez 2002, for the case of labor supply).

The analysis can be generalized, albeit at the cost of some analytical complexity, to the case in which the marginal benefits of the public good are a decreasing function of public expenditure.

The lobby game can be solved by first computing the equilibrium in the policy variables at the second stage by maximizing Eq. (16), which ignores the nonnegativity constraints on political contributions. The latter can then be checked ex-post, after having computed the equilibrium net payoffs of the lobby groups, \(({\hat{\Pi }}_{aj}^{*},{\hat{\Pi }} _{bj}^{*})\), at the first stage of the game. However, in the present work we do not solve for the first stage of the game, since we are not interested in the distributional effects of lobbying due to the monetary transfers from the lobby groups to the policy maker. We focus only on the second stage of the game, where lobbying impacts on fiscal policy in terms of efficiency and inter-regional redistribution.

Social welfare, as defined in Eq. (21), represents a linear aggregation, with uniform weights, of net welfare of resident agents (gross welfare less political contributions paid to the local policy maker), and policy maker’s welfare (political contributions). Representing a pure transfer from lobbyists to policy makers, political contributions cancel out from the expression for social welfare.

Although we have assumed that there are \(J>1\) identical localities of each type j, \(j=1,2\), to ease the notation, and without loss of generality, we compute national aggregates by considering one locality of each type only.

The specification of the utility function (1) is \(\phi ^{i}=1-5\left[ \varepsilon _i / (1+\varepsilon _i)\right] x_{ij}^{(1+\varepsilon _{i})/\varepsilon _{i}}\), that gives the supply function \({{\tilde{x}}}_{ij}= \frac{1}{5}\left[ (1-t_{ij})p_{ij}\right] ^{\varepsilon _{i}}\). Second-order conditions for a maximum are satisfied in all numerical computations, and the solution is always unique.

For given productivity parameters \((p_{k1},p_{k2})\), the relative fiscal-capacity gap on tax base k, \(({\bar{z}}_{k2}-{\bar{z}}_{k1})/{\bar{z}}_{k}\), is an increasing function of its elasticity \(\varepsilon _{k}\). Hence, in order to isolate the role of the tax-base elasticity in the determination of the optimal equalization rate, in model II.0 the parameters \((p_{k1},p_{k2})\) are adjusted such that, for both \(\varepsilon _{a}=.2\) and \(\varepsilon _{b}=.6\), the relative fiscal-capacity gap is the same as in the benchmark model I.0, where \(\varepsilon _{a}=\varepsilon _{b}=.4\).

The optimal degree of progressivity of the program is also higher the more pronounced are the preferences of the central policy maker for redistribution, here expressed by the parameter \(\psi \).

It can be optimal not to equalize tax base a. The corner solution \(\theta _{a}^{*}=0\) occurs if, for a given productivity gap \(p_{a2}/p_{a1}>1\), the lobby power gap \(\lambda _{b}/\lambda _{a}>1\) is above a given threshold; or, conversely, if, for a given lobby power gap, the productivity gap is below a given threshold. In this situation, it is optimal to equalize at a positive rate the actual, rather than the standard, tax revenues, of tax base a. On this point, see the working paper version of the present work (Esteller-Moré et al. 2015).

To derive the policy choices under the influence of lobbying, we ignore, as explained in footnote 5, the nonnegativity constraint on political contributions.

We do not model how uniformity of the equalization rates can be imposed; if, for instance, by a legal provision or by a superior constitutional rule. We simply consider the impact of the restriction on social welfare.

We thank one referee for urging us to consider these issues. The results, obtained by means of numerical simulations, are available upon request.

References

Albouy, D. (2012). Evaluating the efficiency and equity of federal fiscal equalization. Journal of Public Economics, 96, 824–839.

Baretti, C., Huber, B., & Lichtblau, K. (2002). A tax on tax revenue: The incentive effects of equalizing transfers: Evidence from Germany. International Tax and Public Finance, 9, 631–649.

Bernheim, B. D., & Whinston, M. D. (1986a). Common agency. Econometrica, 54, 923–942.

Bernheim, B. D., & Whinston, M. D. (1986b). Menu actions, resource allocation, and economic influence. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 101, 1–31.

Blöchliger, H., & Charbit, C. (2008). Fiscal equalisation. OECD Economic Studies No. 44, 2008/1.

Boadway, R. (2006). Intergovernmental redistributive transfers: efficiency and equity. In E. Ahmad & G. Brosio (Eds.), Handbook of fiscal federalism. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Boadway, R., & Flatters, F. (1982). Efficiency and equalization payments in a central system of government: A synthesis and extension of recent results. Canadian Journal of Economics, 15, 613–633.

Bordignon, M., Manasse, P., & Tabellini, G. (2001). Optimal regional redistribution under asymmetric information. American Economic Review, 91, 709–723.

Brusco, S., Colombo, L., & Galmarini, U. (2014). Tax differentiation, lobbying, and welfare. Social Choice and Welfare, 42, 977–1006.

Buchanan, J., & Goetz, C. (1972). Efficiency limits of fiscal mobility: An assessment of the Tiebout model. Journal of Public Economics, 1, 25–43.

Bucovetsky, S., & Smart, M. (2006). The efficiency consequences of local revenue equalization: Tax competition and tax distortions. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 8, 119–144.

Buettner, T. (2006). The incentive effect of fiscal equalization transfers on tax policy. Journal of Public Economics, 90, 477–497.

Dahlberg, M., & Johansson, E. (2002). On the vote-purchasing behavior of incumbent governments. American Political Science Review, 96, 27–47.

Dahlby, B. (1996). Fiscal externalities and the design of intergovernmental grants. International Tax and Public Finance, 3, 397–412.

Dahlby, B., & Wilson, L. S. (1994). Fiscal capacity, tax effort, and optimal equalization grants. Canadian Journal of Economics, 27, 657–672.

Dixit, A., Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1997). Common agency and coordination: General theory and application to government policy making. Journal of Political Economy, 105, 752–769.

Dixit, A., & Londregan, J. (1996). The determinants of success of special interests in redistributive politics. The Journal of Politics, 58, 1132–1155.

Dixit, A., & Londregan, J. (1998). Ideology, tactics, and efficiency in redistributive politics. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113, 497–529.

Esteller-Moré, A., Galmarini, U., & Rizzo, L. (2012). Vertical tax competition and consumption externalities in a federation with lobbying. Journal of Public Economics, 96, 295–305.

Esteller-Moré, A., Galmarini, U., & Rizzo, L. (2015). Fiscal equalization under political pressures. Document de treball de l’IEB, 2015/21.

Esteller-Moré, A., & Solé-Ollé, A. (2002). Tax setting in a federal system: The case of personal income taxation in Canada. International Tax and Public Finance, 9, 235–257.

Flatters, F., Henderson, V., & Mieszkowski, P. (1974). Public goods, efficiency, and regional fiscal equalization. Journal of Public Economics, 3, 99–112.

Gordon, R. H., & Cullen, J. B. (2011). Income redistribution in a federal system of governments. Journal of Public Economics, 96, 1100–1109.

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1994). Protection for sale. American Economic Review, 84, 833–850.

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (2001). Special interest politics. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Gruber, J., & Saez, E. (2002). The elasticity of taxable income: Evidence and implications. Journal of Public Economics, 84, 1–32.

Hettich, W., & Winer, S. L. (1988). Economic and political foundations of tax structure. American Economic Review, 78, 701–712.

Köthenbuerger, M. (2002). Tax competition and fiscal equalization. International Tax and Public Finance, 9, 391–408.

Kotsogiannis, C., & Schwager, R. (2008). Accountability and fiscal equalization. Journal of Public Economics, 92, 2336–2349.

Larcinese, V., Rizzo, L., & Testa, C. (2006). Allocating the U.S. Federal budget to the States: The impact of the President. The Journal of Politics, 68, 447–456.

Levitt, S., & Snyder, J. (1995). Political parties and the distribution of federal outlays. American Journal of Political Science, 39, 958–980.

Lockwood, B. (1999). Inter-regional insurance. Journal of Public Economics, 72, 1–37.

OECD. (2013). Fiscal federalism 2014: Making decentralisation work. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Panagariya, A., & Rodrik, D. (1993). Political-economy arguments for a uniform tariff. International Economic Review, 34, 685–703.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2000). Political economics: Explaining economic policy. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rizzo, L. (2008). Local government responsiveness to federal transfers: Theory and evidence. International Tax and Public Finance, 15, 316–337.

Sato, M. (2000). Fiscal externalities and efficient transfers in a federation. International Tax and Public Finance, 7, 119–139.

Smart, M. (1998). Taxation and deadweight loss in a system of intergovernmental transfers. Canadian Journal of Economics, 31, 189–206.

Smart, M. (2007). Raising taxes through equalization. Canadian Journal of Economics, 40, 1188–1212.

Solé-Ollé, A., & Sorribas-Navarro, P. (2008). The effects of partisan alignment on the allocation of intergovernmental transfers. Differences-in-differences estimates for Spain. Journal of Public Economics, 92, 2302–2319.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Editor, Andreas Haufler, and an anonymous referee for insightful comments. Previous versions of this paper circulated under the title “Fiscal-capacity equalization grants with taxpayers lobbying” and were presented at the 68th IIPF Congress, Dresden, August 16–19, 2012, at the V Workshop on Fiscal Federalism, IEB, Barcelona, June 13–14, 2013, at the PET Conference, Lisbon, July 5–7, 2013. We thank Lisa Grazzini and seminar participants for useful comments. The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from ECO2015-63591R (MINECO/FEDER, UE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Esteller-Moré, A., Galmarini, U. & Rizzo, L. Fiscal equalization and lobbying. Int Tax Public Finance 24, 221–247 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-016-9415-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-016-9415-2

Keywords

- Fiscal-capacity equalization transfers

- Special interest groups

- Inter-regional redistribution

- Equity-efficiency trade-off

- Uniform versus differentiated equalization