Abstract

This paper analyzes drivers of rising per-pupil public education spending, including Baumol’s “cost disease” effect. Empirical analyses using a large dataset of advanced and developing economies show that the contribution of Baumol’s effect was much smaller than implied by theory. Rather, the increase in per-pupil spending reflects rising wage premiums paid for teachers in excess of market wages, especially in developing countries. The strong wage premium effect suggests that institutional characteristics that govern teachers’ wage-setting are key determinants of education expenditure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Nordhaus (2008) provides evidence that the Baumol’s cost disease hypothesis holds in the USA based on the industry account data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis for the period 1948–2001.

For example, in Portugal, the recurrent cost of public education is large. About 95 % is spent on compensation for teaching and non-teaching staffs (IMF 2013).

The wage premium would be positive and increase over time for two reasons: (a) a higher skill premium for teachers and (b) higher rent payments, for example, because of strong collective bargaining power of labor union in the education sector. Positive union wage effect in education is found around the world in the literature Geeta and Teal (2010) for India; Lemke (2004) for the USA; and Liang (2000) for Latin American countries.

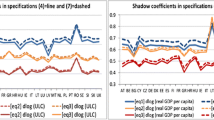

Additional empirical results as well as details about the specification of panel unit root and cointegration tests are available in the working paper version of this paper (Nose 2015).

The Baumol’s effect might be stronger if the sample could cover earlier years before 1995. However, the Baumol’s effect on PEE remains to be weak in any empirical models used in later subsections, which consistently provides little support for the Baumol’s hypothesis in education.

The estimates remain robust when per capita GDP growth and the change in teacher-pupil ratio are replaced with per-pupil GDP growth and the change in school-age population.

Glewwe and Kremer (2006) and UNESCO (2011) point out that there is scarcity of trained teachers at the primary level especially in SSA and South Asia, where the student-teacher ratio is quite high compared with other regions. While the access to basic education is still limited in low-income countries, Barro and Lee (2015) and Hanushek and Woessmann (2015) also emphasized that the quality of spending is more critical than the quantity to fill the gap in school attainment and achievement between developed and developing countries.

Psacharopoulos and Patrinos (2004) presents the latest estimates of the return to education covering 98 countries, which shows (a) falling returns to education as the economy develops and (b) increasing private returns to higher education. The returns are estimated to be the highest for developing countries, especially in Latin America and the SSA.

The sample omits many LICs as teachers’ wage data are not available. As the government needs to pay competitive salaries as other occupations to attract skilled workers in education sector especially in LICs, this sample selection is likely to attenuate the Baumol’s effect and the wage premium effect for low-income groups, and therefore, the estimates in Table 4 would only represent the lower bound of the true effect.

In contrast, the vector error correction estimate found that the long-term relationship between real GDP per capita and public education spending is stronger in non-advanced economies than advanced economies as consistent with the Wagner’s law. Akitoby et al. (2006) also found the similar supporting evidence that the Wagner’s law holds for general government spending in developing countries. The result is available upon request.

References

Akitoby, B., Clements, B., Gupta, S., & Inchauste, G. (2006). Public spending, voracity, and Wagner’s law in developing countries. European Journal of Political Economy, 22, 908–924.

Asadullah, M. (2006). Pay differences between teachers and other occupations: Some empirical evidence from Bangladesh. Journal of Asian Economics, 17, 1044–1065.

Barro, R., & Lee, W. (2015). Education matters: Global schooling gains from the 19th to the 21st century. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bates, L., & Santerre, R. (2013). Does the U.S. health care sector suffer from Baumol’s cost disease? Evidence from the 50 states. Journal of Health Economics, 32, 386–391.

Baumol, W. (1967). Macroeconomics of unbalanced growth: The anatomy of urban crisis. American Economic Review, 57(3), 415–426.

Baumol, W., Ferranti, D., Malach, M., Pablos-Mndez, A., Tabish, H., & Wu, L. (2012). The cost disease: Why computers get cheaper and health care doesn’t. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Busemeyer, M. (2007). Determinants of public education spending in 21 OECD democracies, 1980–2001. Journal of European Public Policy, 14(4), 582–610.

Carrion-i-Silvestre, J. (2005). Health care expenditure and GDP: Are they broken stationary? Journal of Health Economics, 24, 839–854.

Clements, B., Gupta, S., Karpowicz, I., & Tareq, S. (2010). Evaluating government employment and compensation. Technical notes and manuals. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Colombier, C. (2012). Drivers of health care expenditure: Does Baumol’s cost disease loom large? FiFo discussion paper no. 12–5.

Fernandez, R., & Rogerson, R. (2001). The determinants of public education expenditures: Longer-run evidence from the states. Journal of Education Finance, 27, 567–584.

Geeta, K., & Teal, F. (2010). Teacher unions, teacher pay and student performance in India: A pupil fixed effects approach. Journal of Development Economics, 91(2), 278–288.

Gerdtham, U., & Lothgren, M. (2000). On stationarity and cointegration of international health expenditure and GDP. Journal of Health Economics, 19, 461–475.

Glewwe, P., & Kremer, M. (2006). Schools, teachers, and education outcomes in developing countries. In E. Hanushek & F. Welch (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of education (Vol. 2, Chap. 16, pp. 945–1017). Amsterdam: North Holland Publishing.

Gradstein, M., & Kaganovich, M. (2004). Aging population and education finance. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 2469–2485.

Grigoli, F. (2014). A hybrid approach to estimating the efficiency of public spending on education in emerging and developing economies. IMF working paper WP/14/19.

Gupta, S., & Verhoeven, M. (2001). The efficiency of government expenditure: Experiences from Africa. Journal of Policy Modeling, 23, 433–467.

Hanushek, E., & Rivkin, S. (1997). Understanding the twentieth-century growth in U.S. school spending. Journal of Human Resources, 32(1), 35–68.

Hanushek, E., & Woessmann, L. (2015). The knowledge capital of nations: education and the economic growth. CESifo Book Series. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Hartwig, J. (2008). What drives health care expenditure? Baumol’s model of ‘unbalanced growth’ revisited. Journal of Health Economics, 27, 603–623.

Hazans, M. (2010). Teacher pay, class size and local governments: Evidence from the Latvian reform. IZA discussion paper no. 5291.

IMF. (2010). Macro-fiscal implications of health care reform in advanced and emerging economies. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

IMF. (2013). Portugal: Rethinking the state—Selected expenditure reform options. IMF country report no. 13/6, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

IMF. (2014). Public expenditure reform: Making difficult choices. Fiscal Monitor, April, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Lemke, R. (2004). Estimating the union wage effect for public school teachers when all teachers are unionized. Eastern Economic Journal, 30(2), 273–291.

Liang, X. (2000). Teacher pay in 12 Latin American countries: How does teacher pay compare to other professions? What determines teacher pay? Who are the teachers? Latin America and the Caribbean Regional Office: World Bank.

Lovell, M. (1978). Spending for education: The exercise of public choice. Review of Economics and Statistics, 60(4), 487–495.

Medeiros, J., & Schwierz, C. (2013). Estimating the drivers and projecting long-term public health expenditure in the European Union: Baumol’s cost disease revisited. European Commission, Economic Papers 507.

Mizala, A., & Nopo, H. (2012). Evolution of teachers’ salaries in Latin America at the turn of the 20th century: How much are they (under or over) paid? IZA discussion paper no. 6806.

Montanino, A., Przywara, B. & Young, D. (2004). Investment in education: The implications for economic growth and public finances. European Commission, Economic papers 217.

Nordhaus, W. (2008). Baumol’s diseases: A macroeconomic perspective. The B.E Journal of Macroeconomics, 8(1), 1–37.

Nose, M. (2015). Estimation of drivers of public education expenditure: Baumol’s effect revisited. IMF Working Paper WP/15/178.

Poterba, M. (1997). Demographic structure and the political economy of public education. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 16(1), 48–66.

Psacharopoulos, G., & Patrinos, H. (2004). Returns to investment in education: A further update. Education Economics, 12(2), 111–134.

Schultz, P. (1988). Education investments and returns. In H. Chenery & T. N. Srinivasan (Eds.), Handbook of development economics (Vol. I, Chap. 13, pp. 543–630. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2011). Financing education in sub-Saharan Africa: Meeting the challenges of expansion, equity, and quality. Paris: UNESCO.

Verhoeven, M., Gunnarsson, V., & Carcillo, S. (2007). Education and health in G7 countries: Achieving better outcomes with less spending. IMF working paper WP/07/263.

Wagner, A. (1883). Three extracts on public finance. (Translated and reprinted in Musgrave, R. A. & Peacock, A. T. (Ed.), Classics in the theory of public finance. London: Macmillan, 1958).

Wolff, E., Baumol, W., & Saini, A. (2014). A comparative analysis of education costs and outcomes: The United States vs. other OECD countries. Economics of Education Review, 39, 1–21.

Zymelman, M., & DeStephano, J. (1989). Primary school teachers’ salaries in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank discussion paper 45, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to Andreas Haufler, two anonymous referees, Vitor Gaspar, Sanjeev Gupta, David Coady, Masahiro Nozaki, Baoping Shang, Benedict Clements, and seminar participants at the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department for insightful comments. The views expressed herein are those of the author and should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Data description

Appendix: Data description

The following 61 countries are included as the main sample in our econometric analysis.

The following series are used for the analysis in the main text.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nose, M. Estimation of drivers of public education expenditure: Baumol’s effect revisited. Int Tax Public Finance 24, 512–535 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-016-9410-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-016-9410-7