Abstract

Land taxes can increase production in the manufacturing sector and enhance land conservation at the same time, which can lead to overall macroeconomic growth. Existing research emphasizes the non-distorting properties of land taxes (when fixed factors are taxed) as well as growth-enhancing impacts (when asset portfolios are shifted to reproducible capital). This paper furthers the neoclassical perspective on land taxes by endogenizing land allocation decisions in a multi-sector growth model. Based on von Thünen’s observation, agricultural land is created from wilderness through conversion and cultivation, both of which are associated with costs. In the steady state of our general equilibrium model, land taxes not only may reduce land consumption (associated with environmental benefits) but may also affect overall economic output, while leaving wages and interest rates unaffected. When labor productivity is higher in the manufacturing than in the agricultural sector and agricultural and manufactured goods are substitutes (or the economy is open to world trade), land taxes increase aggregate economic output. There is a complex interplay of conservation policy, technological change and land taxes, depending on consumer preferences, sectoral labor productivities and openness-to-trade. Our model introduces a new perspective on land taxes in current policy debates on development, tax reforms as well as forest conservation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Managed and degraded forests provide these social benefits to a substantially lower extent (Gibson et al. 2011): Carbon storage in above-ground biomass is only half for tropical forest plantations compared to tropical primary forest (IPCC 2006); likewise many species are habituated only in primary forests (Barlow et al. 2007)

Also, Almeida and Uhl (1995) discusses the impact of Brazil’s rural land tax, which was established in 1964. This tax scheme granted tax discounts for the share of land utilized for production, providing incentives for landowners to deforest their land.

The consideration of an ad-valorem tax is structurally equivalent in the steady state. As shown in the Appendix, it is possible to calculate for each unit tax the equivalent ad-valorem tax and vice versa. Due to the monotony of the transformation, the subsequent results derived for the unit tax hold qualitatively also for an ad-valorem tax.

This concept dates back to Pigou (1920) and taxes following this principle are also called Pigouvian taxes.

All policies are evaluated for an interior solution of land allocation. For a corner solution where all forests are converted to agricultural land, marginal impacts are always zero.

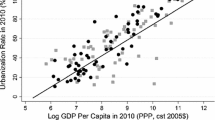

Overall trade restrictiveness is measured using applied tariffs.

Trade policies are also subject to change and many countries are part of regional or bilateral free trade agreements.

References

Anderson, K., Martin, W., & Van der Mensbrugghe, D. (2006). Distortions to world trade: Impacts on agricultural markets and farm incomes. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 28(2), 168–194.

Angelsen, A. (1999). Agricultural expansion and deforestation: Modelling the impact of population, market forces and property rights. Journal of Development Economics, 58(1), 185–218.

Angelsen, A. (2007). Forest cover change in space and time: Combining the von Thunen and forest transition theories. World Bank policy research working paper (4117).

Angelsen, A. (2010). Policies for reduced deforestation and their impact on agricultural production. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(46), 19639–19644.

Arcand, J.-L., Guillaumont, P., & Jeanneney, S. G. (2008). Deforestation and the real exchange rate. Journal of Development Economics, 86(2), 242–262.

Arnott, R. (2005). Neutral property taxation. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 7(1), 27–50.

Arnott, R. J., & Stiglitz, J. E. (1979). Aggregate land rents, expenditure on public goods, and optimal city size. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 93(4), 471–500.

Arrow, K. J. (1962). The economic implications of learning by doing. The Review of Economic Studies, 29(3), 155–173.

Banzhaf, H. S., & Lavery, N. (2010). Can the land tax help curb urban sprawl? Evidence from growth patterns in Pennsylvania. Journal of Urban Economics, 67(2), 169–179.

Barlow, J., Gardner, T. A., Araujo, I. S., Ávila-Pires, T. C., Bonaldo, A. B., Costa, J. E., et al. (2007). Quantifying the biodiversity value of tropical primary, secondary, and plantation forests. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(47), 18555–18560.

Barro, R. J., & Sala-i Martin, X. (2003). Economic growth (Vol. 1). Cambridge: MIT Press Books.

Barua, S. K., Lintunen, J., Uusivuori, J., & Kuuluvainen, J. (2014). On the economics of tropical deforestation: Carbon credit markets and national policies. Forest Policy and Economics, 47, 36–45.

Barua, S. K., Uusivuori, J., & Kuuluvainen, J. (2012). Impacts of carbon-based policy instruments and taxes on tropical deforestation. Ecological Economics, 73, 211–219.

Beckmann, M. J. (1972). Von Thünen revisited: A neoclassical land use model. The Swedish Journal of Economics, 74(1), 1–7.

Binswanger, H. P. (1991). Brazilian policies that encourage deforestation in the Amazon. World Development, 19(7), 821–829.

Bohn, H., & Deacon, R. T. (2000). Ownership risk, investment, and the use of natural resources. American Economic Review, 90(3), 526–549.

Borlaug, N. E. (2002). Feeding a world of 10 billion people: The miracle ahead. Vitro Cellular and Developmental Biology-Plant, 38(2), 221–228.

Brueckner, J. K., & Kim, H.-A. (2003). Urban sprawl and the property tax. International Tax and Public Finance, 10(1), 5–23.

Busch, J., Lubowski, R. N., Godoy, F., Steininger, M., Yusuf, A. A., Austin, K., et al. (2012). Structuring economic incentives to reduce emissions from deforestation within Indonesia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(4), 1062–1067.

Cotula, L., & Vermeulen, S. (2009). Deal or no deal: The outlook for agricultural land investment in Africa. International Affairs, 85(6), 1233–1247.

de Almeida, O. T., & Uhl, C. (1995). Brazil’s rural land tax: Tool for stimulating productive and sustainable land uses in the Eastern Amazon. Land Use Policy, 12(2), 105–114.

De Groot, R., Brander, L., van der Ploeg, S., Costanza, R., Bernard, F., Braat, L., et al. (2012). Global estimates of the value of ecosystems and their services in monetary units. Ecosystem Services, 1(1), 50–61.

Deaton, A., & Laroque, G. (2001). Housing, land prices, and growth. Journal of Economic Growth, 6(2), 87–105.

Drazen, A., & Eckstein, Z. (1988). On the organization of rural markets and the process of economic development. The American Economic Review, 78(3), 431–443.

Eaton, J. (1988). Foreign-owned land. The American Economic Review, 78(1), 76–88.

Edenhofer, O., Mattauch, L., & Siegmeier, J. (2015). Hypergeorgism: When rent taxation is socially optimal. FinanzArchiv: Public Finance Analysis, 71(4), 474–505.

Englin, J. E., & Klan, M. S. (1990). Optimal taxation: Timber and externalities. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 18(3), 263–275.

Feldstein, M. (1977). The surprising incidence of a tax on pure rent: A new answer to an old question. The Journal of Political Economy, 85(2), 349–360.

Foster, A. D., & Rosenzweig, M. R. (2003). Economic growth and the rise of forests. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(2), 601–637.

Friedman, M. (1 December 1978). The Times Herald, Norristown.

Fuss, S., Canadell, J. G., Peters, G. P., Tavoni, M., Andrew, R. M., Ciais, P., et al. (2014). Betting on negative emissions. Nature Climate Change, 4(10), 850–853.

George, H. (1879). Progress and poverty. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Gibson, L., Lee, T. M., Koh, L. P., Brook, B. W., Gardner, T. A., Barlow, J., et al. (2011). Primary forests are irreplaceable for sustaining tropical biodiversity. Nature, 478(7369), 378–381.

Goulder, L. H. (1995). Environmental taxation and the double dividend: A reader’s guide. International Tax and Public Finance, 2(2), 157–183.

Herrendorf, B., Rogerson, R., & Valentinyi, Á. (2013). Growth and structural transformation. National Bureau of Economic Research. Technical report.

IPCC. (2006). IPCC guidelines for national greenhouse gas inventories.

Irz, X., & Roe, T. (2005). Seeds of growth? Agricultural productivity and the transitional dynamics of the Ramsey model. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 32(2), 143–165.

Jevons, W. S. (1865). The coal question: An inquiry concerning the progress of the nation, and the probable exhaustion of the coal-mines. London: Macmillan.

Koethenbuerger, M., & Poutvaara, P. (2009). Rent taxation and its intertemporal welfare effects in a small open economy. International Tax and Public Finance, 16(5), 697–709.

Kongsamut, P., Rebelo, S., & Xie, D. (2001). Beyond balanced growth. The Review of Economic Studies, 68(4), 869–882.

Koskela, E., & Ollikainen, M. (2003). Optimal forest taxation under private and social amenity valuation. Forest Science, 49(4), 596–607.

Looi Kee, H., Nicita, A., & Olarreaga, M. (2009). Estimating trade restrictiveness indices*. The Economic Journal, 119(534), 172–199.

Martin, W., & Mitra, D. (2001). Productivity growth and convergence in agriculture versus manufacturing*. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 49(2), 403–422.

Matsuyama, K. (1992). Agricultural productivity, comparative advantage, and economic growth. Journal of Economic Theory, 58(2), 317–334.

Mattauch, L., Siegmeier, J., Edenhofer, O., & Creutzig, F. (2013). Financing public capital through land rent taxation: A macroeconomic Henry George theorem.

Mills, D. E. (1981). The non-neutrality of land value taxation. National Tax Journal, 34(1), 125–129.

Muhammad, A., Seale, J. L., Meade, B., & Regmi, A. (2011). International evidence on food consumption patterns: An update using 2005 international comparison program data. USDA-ERS technical bulletin (1929).

Petrucci, A. (2006). The incidence of a tax on pure rent in a small open economy. Journal of Public Economics, 90(4), 921–933.

Pigou, A. C. (1920). The economics of welfare. London: Macmillan.

Popp, A., Dietrich, J. P., Lotze-Campen, H., Klein, D., Bauer, N., Krause, M., et al. (2011). The economic potential of bioenergy for climate change mitigation with special attention given to implications for the land system. Environmental Research Letters, 6(3), 034017.

Ricardo, D. (1817). On the principles of political economy and taxation. London: John Murray.

Salin, D. (2013). Soybean transportation guide: Brazil (May 2013). Technical report. Agricultural Marketing Service, US Dept. of Agriculture.

Solow, R. M. (1974). Intergenerational equity and exhaustible resources. The Review of Economic Studies, 41(5), 29–45.

Stiglitz, J. (1974). Growth with exhaustible natural resources: Efficient and optimal growth paths. The Review of Economic Studies, 41(5), 123–137.

Tahvonen, O. (1995). Net national emissions, co 2 taxation and the role of forestry. Resource and Energy Economics, 17(4), 307–315.

Timmer, M. M., de Vries, G., & de Vries, K. (2014). Patterns of structural change in developing countries. GGDC research memorandum 149.

von Thünen, J. H. (1826). Der isolierte Staat in Beziehung auf Nationalökonomie und Landwirtschaft. Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer (reprinted 1966).

Wildasin, D. E. (1982). More on the neutrality of land taxation. National Tax Journal, 35(1), 105–108.

World Bank. (2007). World development report 2008. Agriculture for development. Washington, DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jan Börner, Johanna Wehkamp and one anonymous reviewer for helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Unit versus ad-valorem taxes on land

Appendix: Unit versus ad-valorem taxes on land

In this section we consider two forms of land value taxes. The first applies to the price of land p and the second to the price of land net of transportation cost. As we do not model spatial land price differentials explicitly, the latter land price net transportation costs would be more comparable to land prices observed on land markets.

1.1 Tax on land price

Considering an ad-valorem tax on land \(\tau _A\), the profit function of the land owner (8) reads

The equation of motion for the state variable (10) becomes

which leads to the modified steady-state equation for the land allocation (31)

Equivalence between the unit tax \(\tau \) in (31) and the ad-valorem tax \(\tau _A\) in (46) holds if

Hence, for each ad-valorem tax \(\tau _A\), it is possible to calculate the equivalent unit tax \(\tau \) which gives the same allocation in the steady state using (52). Contrary for each unit tax \(\tau \), the equivalent ad-valorem tax \(\tau _A\) can be calculated using (48). Although the transformation of unit taxes into ad-valorem taxes (and vice versa) is nonlinear, it is increasing and monotone as long as \(\tau _A<1\) and \(\tau , \tau _A>0\) (note that \(q(A)<0\) by assumption). Hence, the comparative static analysis on the sign of the impact of land tax changes holds equally for unit and ad-valorem taxes.

1.2 Tax on land price net of transportation costs

Considering an ad-valorem tax on land \(\tau _B\) net of transportation costs, the profit function of the land owner (8) reads

The equation of motion for the state variable (10) becomes

which leads to the modified steady-state equation for the land allocation (31)

Equivalence between the unit tax \(\tau \) in (31) and the ad-valorem tax \(\tau _A\) in (51) holds if

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kalkuhl, M., Edenhofer, O. Ramsey meets Thünen: the impact of land taxes on economic development and land conservation. Int Tax Public Finance 24, 350–380 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-016-9403-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-016-9403-6

Keywords

- Structural shift

- Structural change

- REDD

- Henry George

- Forest conservation

- Sustainability

- Johann Heinrich von Thünen