Abstract

This article interprets the role and significance of the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) in global environmental and energy governance. First, we conduct a comparative analysis of IRENA and other recent innovations in global governance, showing that IRENA stands out with regard to the timing of creation, speed of ratification, and focus of the mandate. Second, we identify three mechanisms through which IRENA can promote the global diffusion of renewable energy: (1) by offering valuable epistemic services to its member states, (2) by serving as a focal point for renewable energy in a scattered global institutional environment, and (3) by mobilizing other international institutions to promote renewable energy. Finally, we reflect on the conditions that could make IRENA’s policies a continued success and on the lessons that the experience with IRENA holds for other attempts at innovation in global governance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

‘China to join International Renewable Energy Agency’, Press release, IRENA, January 14, 2013, http://www.irena.org/News/Description.aspx?NType=N&News_ID=287.

For a different perspective see Ivanova (2009), who argues that UNEP’s functioning as an “anchor organization” for the global environment has been constrained by its formal status, governance, financing structure, and location.

A similar kind of motivation seems to lie behind the new “Renewables Club” (or, in German, “Club der Energiewende-Staaten”) created on June 1, 2013. According to the German Minister for the Environment, Peter Altmaier, the launch of this club of ten “pioneering” countries shows that “[w]e in Germany do not stand alone with our Energiewende, but are a part of a strong group of leaders.” In other words, this new initiative too appears to be the continuation of domestic politics at the international level. The precise goal of the new Club is still somewhat vaguely defined as “to work together as advocates and implementers of renewable energy at global level,” although the Club is clearly also intended to support IRENA, which itself is a member http://www.bmu.de/N50089-1/.

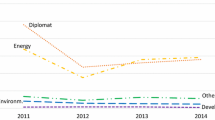

While there is a large literature on why states ratify environmental treaties, and also some research into the temporality and sequentiality of these ratification processes (e.g., Bernauer et al. 2010), to our knowledge no aggregate data are available to compare the pace of ratification across (environmental) treaties. Therefore, we have only included a few treaties and conventions in Fig. 3. They were selected on the basis of availability of information, importance, and relevance as a point of reference.

The figures come from the organizations’ respective websites. Both annual budgets include voluntary contributions and, in the case of the IEA, revenues from the sale of publications.

Abbreviations

- IRENA:

-

International Renewable Energy Agency

- USD:

-

United States dollar

- OPEC:

-

Organization of Petroleum-Exporting Countries

- UN:

-

United Nations

- REN21:

-

Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century

- UNEP:

-

United Nations Environment Programme

- IEA:

-

International Energy Agency

- EU:

-

European Union

- CCS:

-

Carbon capture and storage

- EPO:

-

European Patent Office

- OECD:

-

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

- REEEP:

-

Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Program

- GBEP:

-

Global Bioenergy Partnership

- FAO:

-

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

- UNFCCC:

-

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

- JREC:

-

Johannesburg Renewable Energy Coalition

References

Abbott, K. W., Green, J. F., & Keohane, R. O. (2013). Organizational ecology in world politics: Institutional density and organizational strategies. Paper presented at ISA, San Francisco, April 2013.

Aklin, M., & Urpelainen, J. (2013). Political competition, path dependence, and the strategy of sustainable energy transitions. American Journal of Political Science, 57(3), 643–658.

Asif, M., & Muneer, T. (2007). Energy supply, its demand and security issues for developed and emerging economies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 11(7), 1388–1413.

Baccini, L., & Urpelainen, J. (2012). International institutions and domestic politics: Can preferential trading agreements help leaders promote economic reform? Journal of Politics. http://eprints.imtlucca.it/id/eprint/77

Barrett, S. (2009). The coming global climate-technology revolution. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23(2), 53–75.

Bauer, S., Busch, P. O., & Siebenhuener, B. (2009). Treaty secretariats in global environmental governance. In: F. Biermann & S. Bauer (Eds.), International organizations in global environmental governance (pp. 174–191). London: Routledge.

Bernauer, T., Kalbhenn, A., Koubi, V., & Spilker, G. (2010). A comparison of international and domestic sources of global governance dynamics. British Journal of Political Science, 40(3), 509–538.

Biermann, F., & Siebenhuener, B. (2009). The role and relevance of international bureaucracies: Setting the stage. In: F. Biermann & B. Siebenhuener (Eds.), Managers of global change: The influence of environmental bureaucracies (pp. 1–14). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Brass, J. N., Carley, S., MacLean, L. M., & Baldwin, E. (2012). Power for development: A review of distributed generation projects in the developing world. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 37, 107–136.

British Petroleum. (2013). Statistical review of world energy. Available at http://www.bp.com/statisticalreview.

Burke, P. J. (2010). Income, resources, and electricity mix. Energy Economics, 32(3), 616–626.

Cass, L. R. (2012). The symbolism of environmental policy: Foreign policy commitments as signaling tools. In: P. G. Harris (Ed.), Environmental change and foreign policy: Theory and practice (pp. 41–56) London: Routledge.

Chayes, A., & Chayes, A. H. (1995). The new sovereignty: Compliance with international regulatory agreements. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Cheon, A., & Urpelainen, J. (2012). Oil prices and energy technology innovation: An empirical analysis. Global Environmental Change, 22(2), 407–417.

Cole, W. M. (2005). Sovereignty relinquished? Explaining commitment to the international human rights covenants, 1966–1999. American Sociological Review, 70(3), 472–495.

Colgan, J. D. (2013). The emperor has no clothes: The limits of OPEC in the global oil market. International Organization (forthcoming).

Collier, P., & Venables, A. J. (2012). Greening Africa? Technologies, endowments and the latecomer effect. Energy Economics, 34(S1), S75–S84.

Dai, X. (2005). Why comply? The domestic constituency mechanism. International Organization, 59(2), 363–398.

DeRose, A. M., La Vina, A. G., & Hoff, G. (2003). The outcomes of Johannesburg: Assessing the world summit on sustainable development. SAIS Review, 23(1), 53–70.

Downs, G. W., Rocke, D. M., & Barsoom, P. N. (1996). Is the good news about compliance good news about cooperation? International Organization, 50(3), 379–406.

Downs, G. W., Rocke, D. M., & Barsoom, P. N. (1998). Managing the evolution of multilateralism. International Organization, 52(2), 397–419.

Florini, A. (2011). The International Energy Agency in global energy governance. Global Policy, 2(s1), 40–50.

Gallup. (2011). Fewer Americans, Europeans view global warming as a threat. Entry available at http://www.gallup.com/poll/147203/Fewer-Americans-Europeans-View-Global-Warming-Threat.aspx.

Gilligan, M. J. (2004). Is there a broader-deeper trade-off in international multilateral agreements? International Organization, 58(3), 459–484.

Hirschl, B. (2009). International renewable energy policy: Between marginalization and initial approaches. Energy Policy, 37(11), 4407–4416.

IEA. (2010). IEA activities on renewable energy: An update. Available at http://www.iea.org/IEAnews/0310/REN_Brochure.pdf.

IRENA. (2009). Statute of the International Renewable Energy Agency. Available at http://www.irena.org/menu/index.aspx?mnu=cat&PriMenuID=13&CatID=126.

IRENA. (2011). Decision regarding the work programme and budget for 2011. Available at http://www.irena.org/DocumentDownloads/WP2011/A_1_DC_8.pdf.

IRENA. (2013a). Decision regarding the work programme and budget for 2013. Available at http://www.irena.org/DocumentDownloads/WP2013.pdf.

IRENA. (2013b). Report of the fourth meeting of the council of the International Renewable Energy Agency: List of participants. Available at http://www.irena.org/documents/uploadDocuments/4thCouncil/C_4_SR_1.pdf.

Ivanova, M. (2009). UNEP as anchor organization for the global environment. In: F. Biermann, S. Bernd & S. Anna (Eds.), International organizations in global environmental governance (pp. 151–173). London: Routledge.

Kalkuhl, M., Edenhofer, O., & Lessmann, K. (2012). Learning or lock-in: Optimal technology policies to support mitigation. Resource and Energy Economics, 34(1), 1–23.

Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S. I. (2010). The United Nations and global energy governance: Past challenges, future choices. Global Change, Peace and Security, 22(2), 175–195.

Ki-Moon, B. (2011). Sustainable energy for all: A vision statement by Ban Ki-Moon, Secretary-General of the United Nations, November 2011.

Kingdon, J. W. (1984). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Boston: Little, Brown.

Krasner, S. D. (1991). Global communications and national power: Life on the Pareto frontier. World Politics, 43(3), 336–366.

Lesage, D., Van de Graaf, T., & Westphal, K. (2010). Global energy governance in a multipolar world. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Mansfield, E. D. (1995). Review: International institutions and economic sanctions. World Politics, 47(4), 575–605.

Meyer, T. (2012). Global public goods, governance risk, and international energy. Duke Journal of Comparative and International Law, 22, 319–348.

Meyer, T. (2013). Epistemic institutions and epistemic cooperation in international environmental governance. Transnational Environmental Law, 2(2), 15–44.

Moravcsik, A. (1997). Taking preferences seriously: A liberal theory of international politics. International organization, 51(04), 513–553.

Orsini, A., Morin, J. F., & Young, O. (2013). Regime complexes: A buzz, a boom, or a boost for global governance? Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, 19(1), 27–39.

Park, J., Conca, K., & Finger, M. (2008). The death of Rio environmentalism. In: J. Park, K. Conca & M. Finger (Eds.), The crisis of global environmental governance: Towards a new political economy of sustainability (pp. 1–12) London: Routledge.

Pauwelyn, J., Wessel, R., & Wouters, J. (2012). The stagnation of international law. KU Leuven, Working paper no. 97, October 2012.

Pew. (2013). Who’s winning the clean energy race? 2012 edition. Available at http://www.pewenvironment.org/uploadedFiles/PEG/Publications/Report/-clenG20-Report-2012-Digital.pdf.

Pidgeon, N., & Fischhoff, B. (2011). The role of social and decision sciences in communicating uncertain climate risks. Nature Climate Change, 1, 35–41.

Poast, P., & Urpelainen, J. (2013). Fit and feasible: Why democratizing states form, not join, international organizations. International Studies Quarterly. doi:10.1111/isqu.12031

Raustiala, K., & Victor, D. G. (2004). The regime complex for plant genetic resources. International Organization, 58(2), 277–309.

REN21. (2012). Renewables global status report: 2012 update. REN21 Secretariat, Paris.

Scheer, H. (2007). Energy autonomy: The economic, social and technological case for renewable energy. London: Earthscan.

Stavins, R. N. (2010). Options for the institutional venue for international climate negotiations. Available at http://belfercenter.ksg.harvard.edu/files/Stavins-Issue-Brief-3.pdf.

Szarka, J. (2007). Why is there no wind rush in France? European Environment, 17(5), 321–333.

UNEP and EPO. (2013). Patents and clean energy technologies in Africa. Report available at http://www.epo.org/clean-energy-africa.

Urpelainen, J. (2012). The strategic design of technology funds for climate cooperation: Generating joint gains. Environmental Science and Policy, 15(1), 92–105.

Van de Graaf, T. (2012). Obsolete or resurgent? The International Energy Agency in a changing global landscape. Energy Policy, 48, 233–241.

Van de Graaf, T. (2013). Fragmentation in global energy governance: Explaining the creation of IRENA. Global Environmental Politics, 13(3), 14–33.

Van de Graaf, T., & Westphal, K. (2011). The G8 and G20 as global steering committees for energy: Opportunities and constraints. Global Policy, 2(s1), 19–30.

Victor, D. G. (2011). Global warming gridlock: Creating more effective strategies for protecting the planet. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wendt, A. (1999), Social theory of international politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

World Bank. (2012). World Bank financing for renewable energy hits record high. Entry available at http://go.worldbank.org/ITW1FVVIJ0.

Worldwatch Institute. (2009). IRENA politics may ‘taint’ agency, advocates say. Eye on Earth. Available at http://www.worldwatch.org/node/6169.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Frank Biermann, Jeff Colgan, Sander Happaerts, Timothy Meyer, and Sarah Van Eynde for commenting on earlier drafts. We also thank the editors of International Environmental Agreements and the anonymous reviewers for their advice. All interviewees are commended for their openness and contribution.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Urpelainen, J., Van de Graaf, T. The International Renewable Energy Agency: a success story in institutional innovation?. Int Environ Agreements 15, 159–177 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-013-9226-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-013-9226-1