Abstract

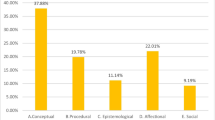

Mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macao, in the Greater China Region, have similar yet different educational systems and curriculum standards, and each has performed well in international tests for science achievement. Using revised Bloom’s taxonomy, this study analyzed and explored the similarities and differences among these four Chinese regions. Some common features of their junior high science curricula were identified: conceptual knowledge represents the largest proportion of the curricula, while meta-cognitive knowledge remains extremely marginalized, and the lower levels of cognitive process represented a significantly larger proportion of the curricula than the higher levels. This study also identified some differences: mainland China, Taiwan, and Macao emphasize the memory of factual and conceptual knowledge, while Hong Kong emphasizes understanding. In addition to conceptual knowledge, Taiwan attaches importance to procedural knowledge, while Hong Kong places more emphasis on factual knowledge. Finally, some recommendations are offered for the reform of the junior high school science curriculum in these four Chinese regions and beyond, and suggestions are made for future comparative studies of science curricula around the world.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Amer, A. (2006). Reflections on Bloom’s revised taxonomy. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 4(1), 213–230.

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., Airasian, P., Cruikshank, K., Mayer, R., Pintrich, P., & Wittrock, M. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy. New York, NY: Longman Publishing.

Anderson, L. (2006). Revised Bloom’s taxonomy. Raleigh, NC: Paper presented at North Carolina Career and Technical Education Curriculum Development Training

Ari, A. (2011). Finding acceptance of Bloom’s revised cognitive taxonomy on the international stage and in Turkey. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 11(2), 767–772.

Bloom, B. S. (Ed.), Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook 1: Cognitive domain. New York, NY: David McKay.

Boyatzis, R. E. (2008). Competencies in the 21st century. Journal of Management Development, 27(1), 5–12.

Chang, C. Y. (2005). Taiwanese science and life technology curriculum standards and earth systems education. International Journal of Science Education, 27(5), 625–638.

Curriculum Development Council. (2001). Learning to learn: Lifelong learning and whole person development. Hong Kong: Government Printer.

Curriculum Development Council. (2002). Science education curriculum guide (Primary 1-Secondary 3). Hong Kong: Government Printer.

Curriculum Development Council. (2017a). Science education key learning area curriculum guide (Primary 1-Secondary 6). Hong Kong: Government Printer.

Curriculum Development Council. (2017b). Supplement to the science education key learning area curriculum guide science (Secondary 1-3). Hong Kong: Government Printer.

Cheng, M. H. M., & Wan, Z. H. (2016). Unpacking the paradox of Chinese science learners: Insights from research into Asian Chinese school students’ attitudes towards learning science, science learning strategies, and scientific epistemological views. Studies in Science Education, 52(1), 29–62.

Choi, K., Lee, H., Shin, N., Kim, S., & Krajcik, J. (2011). Re-conceptualization of scientific literacy in South Korea for the 21st century. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 48(6), 670–697.

DeBoer, G. E. (2011). The globalization of science education. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 48(6), 567–591.

Education and Youth Bureau. (2017). The requirements of basic academic attainments for junior secondary natural science. Retrieved January 25, 2018 from http://www.dsej.gov.mo/crdc/edu/BAA_junior/despsasc-56-2017-anexo_x.pdf

Fisher, R. (2005). Teaching children to think. In Cheltenham. England: Nelson Thornes Ltd.

FitzPatrick, B., & Schulz, H. (2015). Do curriculum outcomes and assessment activities in science encourage higher order thinking. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 15(2), 136–154.

Forehand, M. (2010). Bloom’s taxonomy. Emerging Perspectives on Learning, Teaching, and Technology, 41, 1–9.

Georghiades, P. (2006). The role of metacognitive activities in the contextual use of primary pupils' conceptions of science. Research in Science Education, 36(1), 29–49.

Guo, X. (2016). Key competencies and the framework of curriculum reform in Macao’s non-higher education. Journal of Macao Studies, 4, 43–59. (in Chinese)

Gurria, A. (2014). PISA 2012 results in focus: What 15-year-olds know and what they can do with what they know. Retrieved from OECD website: http://www.oecd.org/pisa/keyfindings/pisa-2012-results-overview.pdf. Accessed 28 April 2018.

Gurria, A. (2016). Pisa 2015 results in focus. PISA in. Focus, 67, 1–14.

Hu, J. (2015). An introduction to junior high school science curriculum in Hong Kong and Singapore: A comparison with the 2011 junior high school science curriculum standards of China. Educational Assessment and Evaluation, 12, 34–40. (in Chinese)

International Education Association. (2016). Distribution of science achievement (8 grade). Retrieved January 25, 2018 from http://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2015/international-results/timss2015/science/student-achievement/distribution-of-science-achievement/

Lau, K. C., & Lam, T. Y. P. (2017). Instructional practices and science performance of 10 top-performing regions in PISA 2015. International Journal of Science Education, 39(15), 2128–2149.

Lee, Y. J., Kim, M., & Yoon, H. G. (2015). The intellectual demands of the intended primary science curriculum in Korea and Singapore: An analysis based on revised Bloom’s taxonomy. International Journal of Science Education, 37(13), 2193–2213.

Lee, Y. J., Kim, M., Jin, Q., Yoon, H. G., & Matsubara, K. (2016). East-Asian primary science curricula: An overview using revised Bloom’s taxonomy. Singapore: Springer.

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom's taxonomy: An overview. Theory Into Practice, 41(4), 212–218.

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Magno, C. (2010). The role of metacognitive skills in developing critical thinking. Metacognition and Learning, 5(2), 137–156.

Martone, A., & Sireci, S. J. (2009). Evaluating alignment between curriculum, assessment, and instruction. Review of Educational Research, 79(4), 1332–1361.

Ministry of Education (MoE). (2001a).The outline of curriculum reform of basic education (official document, in Chinese).

Ministry of Education (MoE). (2001b). Full-time compulsory science curriculum standards (Grade 7–9) (trial edition). Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press. (in Chinese)

Ministry of Education (MoE). (2011). Compulsory junior high school science curriculum standards. Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press. (in Chinese)

Ministry of Education (MOE). (2001). The 1–9 grades science and life technology curriculum standards. Taipei: Ministry of Education. (in Chinese)

Ministry of Education (MOE). (2008). The 1–9 grades science and life technology curriculum standards. Taipei: Ministry of Education. (in Chinese)

National Research Council. (1996). National science education standards. Washington, DC: Author.

National Research Council. (2012). A science framework for K-12 science education: Practices, crosscutting concepts, and core ideas. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Pintrich, P. R. (2002). The role of metacognitive knowledge in learning, teaching, and assessing. Theory Into Practice, 41(4), 219–225.

Porter, A. C. (2006). Curriculum assessment. In J. L. Green, G. Camilli, & P. B. Elmore (Eds.), Handbook of complementary methods in education research (pp. 141–159). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Radmehr, F., & Drake, M. (2017). Revised Bloom’s taxonomy and integral calculus: Unpacking the knowledge dimension. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 48(8), 1206–1224.

Schmidt, W., McKnight, C., Houang, R., Wang, H. C., Wiley, D., Cogan, L., & Wolfe, R. G. (2001). Why schools matter: A cross-national comparison of curriculum and teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Schleicher, A., Zimmer, K., Evans, J., & Clements, N. (2009). PISA 2009 assessment framework: Key competencies in reading, mathematics and science. OECD Publishing (NJ1).

Stemler, S. (2001). An overview of content analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 7(17), 137–146.

Waddington, D., Nentwig, P., & Schanze, S. (Eds.). (2007). Making it comparable: Standards in science education. Münster, Germany: Waxmann.

Wei, B. (2016). School science teaching and learning in Macau: Problems and challenges. In M.-H. Chiu (Ed.), Science education research and practice in Asia - challenges and opportunities (pp. 55–70). Singapore: Springer.

Wei, B., Shieh, J. J., Sze, T. M., Chan, I. N., Yuen, P. K., & Lee, M. Y. (2009). The report of the evaluation onScience Educationin primary and secondary schools in Macau. Macau: University of Macau. (in Chinese)

Zhang, H., Wan, D., & Xue, Y. (2017). An exploration of the characteristics and the reasons of China students’ lower performances in PISA 2015. Journal of Bio-education, 5(1), 1–9. (in Chinese)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, B., Ou, Y. A Comparative Analysis of Junior High School Science Curriculum Standards in Mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macao: Based on Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy. Int J of Sci and Math Educ 17, 1459–1474 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-018-9935-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-018-9935-6