Abstract

This paper examines the impact of local (county-level) house prices on individual self-reported mental health using individual level data from the United States Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System between 2005 and 2011. Exploiting a fixed-effects model that relies on within-county variations, relative to the corresponding changes in other counties, I find that while individuals are likely to experience worse self-reported mental health when local house prices decline, this association is most pronounced for individuals who are least likely to be homeowners. This finding is not consistent with a prediction from a pure wealth mechanism but rather with the hypothesis that house prices act as an economic barometer. I also demonstrate that the association between self-reported mental health and local house prices is not driven by unemployment or foreclosure. The primary result—that lower local house prices have adverse impact on self-reported mental health of homeowners and renters—is consistent with studies using data from the United Kingdom.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The BRFSS provides data on homeownership status only after 2008, but data for 2009 and 2010 contain a lot of missing. See second and third Sections for details.

In 2013, the homeownership rate was 65 %, and the share of housing wealth in total assets was 29 % (Wolff 2014). Moreover, housing accounted for 8.7 % of the household’s wealth for those in the top 1 % of wealth, whereas for the next richest 19 % and the middle three quantile, it accounted for 28 and 62.5 % of the household’s wealth, respectively (Wolff 2014).

Average county-level house prices decreased by 26 % over the period 2005-2011 and 33.5 % over the period 2006-2011. According to Case et al. (2013), housing wealth declined by 35 % from 2005-2009.

Currie and Tekin (2015) focus on the four US states that suffered high rates of foreclosure and show that hospital and emergency room visits for mental health conditions increased with a rise in foreclosures.

The BRFSS does not identify the county of residence for individuals residing in a county with fewer than 50 respondents or a county with adult populations less than or equal to 10,000 residents.

Over the period 2005–2011, the ZHVI is available for 986 counties.

The index is seasonally adjusted. For details on methodology, see http://www.zillow.com/research/zhvi-methodology-6032/. I convert the ZHVI into December 2011 dollar terms using Consumer Price Index data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Mian and Sufi (2009) show that for 2248 zip codes, the house price changes for Fiserv’s Case Shiller Weiss indices and the ZHVI have a correlation coefficient of 0.91. An advantage of the ZHVI data relative to the Federal Housing Finance Agency house price index is that it allows the examination of the impact of the local house price monthly instead of quarterly, and at the county level instead of metropolitan or state level.

I thank a referee for suggesting this figure.

The county house prices (US $) range from 38184 to 7032437. In addition, the mean, 25th percentile, and 75th percentile are 205762, 115190, and 233825, respectively.

Taking the log of house prices ensures the diminishing marginal effects of house prices at higher price levels, which is consistent with diminishing marginal utility of housing wealth (Ratcliffe 2015). Similar to Ruhm (2005) and Tekin et al. (2013), the average of local house prices during the three months ending with the survey month is used, rather than local house prices during only the survey month. However, I also estimate the model using one-month-lagged local house prices and the average of local house prices during the two months ending with the survey month. The results are qualitatively similar and are available from the author upon request.

The unemployment data are from United States Bureau of Labor Statistics Local Area Unemployment Statistics program. As for the local house prices, the average of local unemployment rate during the three months ending with the survey month is used. The correlation between county-level house prices and county-level unemployment rate is −0.1149.

The BRFSS provides repeated cross-sections, and therefore, it is not possible to control for individual-fixed effects. To overcome this limitation, it would be preferable to use longitudinal data, but large longitudinal data set is not publicly available in the US (Ruhm 2005).

This is around 90 % for 2009 and 96 % for 2010.

I thank a referee for suggesting this approach. These characteristics pertain to the household head. CPS data corresponds to previous calendar year. X in Eq. (2) also includes predicted homeownership status \(\times \) month \(\times \) year fixed effects.

These are computed as follows: 0.1286 % = (0.0050/ 3.8883) \(\times \) 100, and 0.0746 % = (0.0029/ 3.8883) \(\times \) 100.

The mental health effect of local house prices will be potentially smaller (in magnitude) for individuals with high homeownership value if house-price decreases are also associated with higher real wages. This could be a possible mechanism as Stroebel and Vavra (2014) show that local house-price decreases lead to lower local retail prices in regions with high homeownership rate but do not have any effect in regions with low homeownership rate. I leave it to future research to thoroughly examine this possibility.

In percentage terms, these represent increases of about 0.4063 and 1.2473 %. However, since a one percentage point increase in the average local unemployment rate represents an increase of 14.82 % (1/6.7484) \(\times \) 100, the implied elasticities are much smaller.

The 25th and 75th percentiles for predicted homeownership values for the sample excluding 2008–2009 are 0.59 and 0.90, respectively, while the mean poor mental health days is 3.8910 days.

The comparison of 0.1799 and 0.1362 % with 0.1286 and 0.0746 % (footnote 20) also suggests that the relationship between local house prices and self-reported mental health has become more stronger (in magnitude) for individuals with predicted homeownership values at the 75th percentile than for individuals at the 25th percentile.

I thank a referee for suggesting this test.

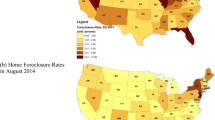

County foreclosure data come from Zillow. Zillow defines the foreclosure rate as the number of homes per 10,000 that were foreclosed in a given month, where a foreclosure is when a homeowner loses their home to their lending institution or it is sold to a third party at an auction. Note that not all counties that have data on house prices have data on foreclosure rate, and so the number of observations is reduced by more than one-third (see Table 5). In addition, Zillow does not have information on foreclosure for Florida, one of the four US states in Currie and Tekin (2015). As for the local house prices, the average of local foreclosure rate during the three months ending with the survey month is used.

The exception is Tekin et al. (2013) who do not find significant impact.

References

Apouey, B., & Clark, A. E. (2015). Winning big but feeling no better? The effect of lottery prizes on physical and mental health. Health Economics, 24(5), 516–538.

Bertrand, M., Duflo, E., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). How much should we trust difference-in-differences estimators? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(1), 249–275.

Case, K. E., Quigley, J. M., & Shiller, R. J. (2013). Wealth effects revisited 1978–2009 (No. w16848). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Charles, K. K., & DeCicca, P. (2008). Local labor market fluctuations and health: Is there a connection and for whom? Journal of Health Economics, 27, 1532–1550.

Cotti, C., Dunn, R. A., & Tefft, N. (2015). The Dow is killing me: Risky health behaviors and the stock market. Health Economics, 24(7), 803–821.

Currie, J., & Tekin, E. (2015). Is there a link between foreclosure and health? American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 7(1), 63–94.

Fichera, E., & Gathergood, J. (2013). House prices, home equity and health. Working paper (No. 13/01). Department of Economics, University of York.

Guerrieri, V., Hartley, D., & Hurst, E. (2010). Endogenous gentrification and housing price dynamics. Working paper (No. w16237). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Leamer, E. E. (2007). Housing is the business cycle (No. w13428). National Bureau of Economic Research.

McInerney, M., & Mellor, J. M. (2012). Recessions and seniors health, health behaviors, and healthcare use: Analysis of the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey. Journal of Health Economics, 31(5), 744–751.

McInerney, M., Mellor, J. M., & Nicholas, L. H. (2013). Recession depression: Mental health effects of the 2008 stock market crash. Journal of Health Economics, 32(6), 1090–1104.

Mian, A. R., & Sufi, A. (2009). The consequences of mortgage credit expansion: Evidence from the US mortgage default crisis. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(4), 1449–1496.

Mian, A., Rao, K., & Sufi, A. (2013). Household balance sheets, consumption, and the economic slump. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(4), 1687–1726.

Mian, A., & Sufi, A. (2014). House of debt: How they (and you) caused the Great Recession, and how we can prevent it from happening again. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ratcliffe, A. (2015). Wealth effects, local area attributes, and economic prospects: On the relationship between house prices and mental wellbeing. Review of Income and Wealth, 61(1), 75–92.

Ruhm, C. J. (2005). Healthy living in hard times. Journal of Health Economics, 24, 341–363.

Stroebel, J., & Vavra, J. (2014). House prices, local demand, and retail prices. Working paper (No. w20710). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Tekin, E., McClellan, C., & Minyard, K. J. (2013). Health and health behaviors during the worst of times: Evidence from the Great Recession. Working paper (No. w19234). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Wolff, E. N. (2014). Household wealth trends in the United States, 1962–2013: What happened over the Great Recession? Working paper (No. w20733). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to my advisor Allen C. Goodman, David Dranove, the editor-in-chief, and the anonymous referee for suggestions that improved the paper. Any remaining errors or omissions are those of the author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Joshi, N.K. Local house prices and mental health. Int J Health Econ Manag. 16, 89–102 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10754-015-9177-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10754-015-9177-x