Abstract

By providing affordable healthcare to many Americans for the first time, the Affordable Care Act increases demand for public mental health services. It is, however, unclear if states’ provision standards for supply of mental health services will be able to accommodate this demand increase. Both the demand and supply of public mental health services vary within states; it is necessary to measure both locally. In this paper, we estimate the prevalence of mental illness within 30 geographical regions in the state of Virginia, a representative example of how many states organize their public mental health systems and how mental illness prevalence can be measured locally. Our methodology extends the analysis in Stern (Health Serv. Outcomes Res. Methods 14:109–155, 2014) by covering an entire state and accounting for peoples’ insurance status. The latter allows us to compare estimates of demand for public mental health services among those 30 geographical regions. We find that over 66,000 uninsured and Medicaid-insured individuals in Virginia are not provided with public mental health services. The deficit varies locally, with several regions having no deficit and others having 5000 or more untreated people. We also estimate that a large portion of the unserved people with mental illness are uninsured but would be insured for mental health services through Medicaid if Virginia were to accept the Medicaid expansion associated with the Affordable Care Act. These results provide evidence that there is significant variation in the demand for and public health systems’ ability to supply mental health services within states. This implies states can better serve populations relying on mental health care by allocating scarce public mental health dollars to localities reflecting their need.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Pearlman (2013) states that the ACA will result in 62.5 million Americans being newly eligible for mental health benefits from new health insurance marketplaces and optional Medicaid expansions.

Burke et al. (2013) note that the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 2010, reports almost 1/3 of people with incomes below 100% of the federal poverty level had some mental illness. Nearly 1/3 of NSDUH respondents enrolled in Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program above the age of 12 were afflicted with a mental illness.

In some cases, though, there is overlap (e.g., New York).

We also focus on Virginia because we have good supply data for Virginia and because the state legislature requested mental illness prevalence estimates for localities throughout the state.

The ACS data is at the Public Use Microdata Area (PUMA) level, which do not have a one-to-one mapping to CSBs. Where PUMAs are located in multiple CSBs, we combine the CSBs into larger composite CSBs.

Kessler et al. (2005) note that their national estimates support previous surveys in suggesting mental disorders are correlated with generally disadvantaged socioeconomic status. Among other results, Muntaner et al. (1998) document an inverse association between income and the likelihood of mental disorders. Konrad et al. (2009) also find significant relationships between age, education, and race and the likelihood of serious mental illness.

Konrad et al. (2009) first use the NCS-R to predict the likelihood an individual has serious mental illness based on the demographic census data. For individuals who are predicted to have serious mental illness, they use the NCS-R to estimate need, and, for individuals without serious mental illness, they use the MEPS data to estimate need.

Joint estimation of the distribution of latent variables associated with X and structural parameters would also produce consistent estimates. But we prefer the two-stage approach because joint estimation is much more CPU-expensive and is more sensitive to the joint normality assumption.

This idea was suggested to us by Wayne-Roy Gayle. Malec and Müller (2008) use a similar methodology but with restricted information on geography in the NHIS.

See Wells et al. (2005) for more detail.

Throughout the analysis, we use 10 independent draws per observation along with antithetic acceleration (Geweke 1988). The use of antithetic acceleration ensures that the mean draw is equal to the mean of the distribution.

The choice of using \( \pm \hat{\sigma }_{\alpha } \) is arbitrary but provides a good measure of the range of prevalence values.

Barker et al. (2004) report the 37% figure. We estimate that 17.8% of people with mental illness are Medicaid recipients. If we interpret the numbers in Perloff et al. (1997) to mean that 19% of private mental health providers have no Medicaid consumers, among 62% of providers, the mean proportion of Medicaid consumers is 4.5% (= 9%/2), and (somewhat arbitrarily) the remaining 19% have a mean proportion of 20% (even though Perloff et al. (1997) is not specific to mental health providers), then the proportion of Medicaid consumers seen by private providers is 6.6%. If Barker et al. (2004) is correct, then we predict that 17.8% × 37% = 6.6% of consumers seen by private providers are Medicaid recipients. Thus, our estimates seem to be consistent with Barker et al. (2004) and Perloff et al. (1997).

A composite CSB is similar to a CSB and defined in Sect. 3.2.

We especially thank Joel Rothemberg and Paul Gilding for their help.

As a general rule, potential clients of CSBs covered by Medicaid are provided with service. Potential clients without insurance are evaluated for service need, potential financing, and other factors in case management. Some are provided with some service immediately, and others are put on waiting lists. People with private insurance are rarely clients of CSBs.

See Stern (2014) for more sample details.

A PUMA is defined to cover at least 100,000 people.

For example, PUMA 51020 corresponds to the combined total area of the Highlands and Mount Rogers CSBs.

CCSB-specific means and standard deviations are available at http://www.people.virginia.edu/~sns5r/resint/localstf/acsdescriptives.xlsx.

We use each consumer's insurance status to calculate mental illness prevalence by insurance type. As described in Sect. 2, this allows us to characterize whether shortages in mental health services are affecting Medicaid or uninsured populations.

These data do not include the number of individuals who received an emergency service because of the way emergency services are reported to the department. Due to the limited nature of emergency services, CSBs report emergency services, assessment and evaluation services, and early intervention services outside of the mental health program area.

All aggregate prevalence estimates by demographic characteristics, some of which are discussed below, are available at http://www.sns5r/resint/localstf/acsdescriptives.xlsx.

It shows that the percentage of people in this age range with Medicare who have poor mental health is also very high, even higher than Medicaid. Since the paper considers only adults younger than 65, this is an exclusively disabled population, and it is not clear if or how this would correlate with the relationship of Medicare and insurance for more traditional Medicare enrollees.

Medicaid pays for psycho-social rehabilitation services, which are not covered by Medicare and rarely covered by private insurance.

The 0.4 factor in the formula is the rule-of-thumb transformation for approximating the marginal effect of probit estimates (e.g., Wooldridge 2002). It represents the density of the standard normal density evaluated at zero. The 19 term is the difference between the upper limit of family income (measured in $1000 observed in the NHIS ($50) and the average family income of people on Medicaid in the ACS, $31.1. The 0.033 term is an estimated effect of having family income above $50,000.

For the remaining analysis, the estimates are biased for Portsmouth and Norfolk because approximately 2 square miles of southwest Norfolk (approximately 14,000 individuals) are included in the Portsmith CCSB.

In some literature, this specification is called isotropic. See Cressie (1993) for a generalization in multiple dimensions.

There are many people with mental illness who choose not to receive services. For example, Wang et al. (2005) find that 41% of those with mental illness based on the NCS-R visit a mental health professional in the previous 12 months, and Stern et al. (2010) find that 12.1% of adults have a self-identified emotional problem limiting their activity, while 7.4% have had a visit with a mental health professional. However, the NHIS, which is used to estimate mental illness prevalence in this paper, uses a self-identifying definition of having a mental illness. The people in the NHIS sample who self-identify as having a mental illness are more likely to seek mental health services than, for example, those identified by the diagnosis algorithm in the NCS-R.

Note that a high proportion of CCSBs have shortages greater than the 37% of estimated Medicaid recipients with mental illness using private providers from Barker et al. (2004).

Virginia DMAS (2014) report that there are over 50,000 uninsured adults in Virginia with serious mental illness (SMI) based on Cunningham (2014). However, it is not clear-cut how the estimates from Virginia DMAS (2014) use the estimates in Cunningham (2014), and Cunningham (2014) provides no information about how its estimate was constructed. Thus, we have no way to compare our significantly lower estimate to it.

As mentioned in Sect. 2.4, this assumption follows the way CSBs operate in actuality.

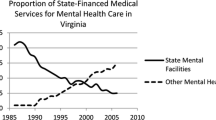

Brown et al. (2015) note that, in Virginia, local funding comprises 22.5% of CSB funding statewide. Comparatively, they note that state funding makes up 24.0%, federal funding accounts for 5.6%, and the remaining 44.6% is from Medicaid and other fee-based sources.

Additionally, in all states, regardless of the decision to expand Medicaid, individuals with family income between 100% and 400% of the FPL are eligible for federal subsidies in the health insurance marketplaces.

References

Alegria, M., Takeuchi, D., Canino, G., Duan, N., Shrout, P., Meng, X.-L., Vega, W., Zane, N., Vila, D., Woo, M., Vera, M., Guarnaccia, P., Aguilar-gaxiola, S., Sue, S., Escobar, J., Lin, K.-m., Gong, F.: Considering context, place and culture: the national latino and asian american study. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 13(4), 208–220 (2006a)

Alegria, M., Vila, D., Woo, M., Canino, G., Takeuchi, D., Vera, M., Febo, V., Guarnaccia, P., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Shrout, P.: Cultural relevance and equivalence in the NLAAS instrument: integrating etic and emic in the development of cross-cultural measures for a psychiatric epidemiology and services study of Latinos. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 13(4), 270–288 (2006b)

Baldwin, M., Marcus, S.: Labor market outcomes of persons with mental disorders. Ind. Relat. 46(3), 481–510 (2007)

Banerjee, S., Wall, M., Carlin, B.: Frailty modeling for spatially correlated survival data, with application to infant mortality in Minnesota. Biostatistics 4(1), 123–142 (2003)

Barker, P., Epstein, J., Hourani, L., Gfroerer, J., Monique Clinton-Sherrod, A., West, N., Shi, W.: Patterns of mental health service utilization and substance use among adults, 2000 and 2001. DHHS Publication No. SMA 04-3901, Analytic Series A-22. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, Rockville, MD (2004)

Brown, C., Guo, D., Stern, S.: Cost and service variation across community service boards for mental health services in Virginia. Unpublished manuscript (2015)

Burke, B., Miller, B., Proser, M., Petterson, S., Bazemore, A., Goplerud, E., Phillips, R.: A needs-based method for estimating the behavioral health staff needs of community health centers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 13(1), 245 (2013)

Chihara, T.: An Introduction to Orthogonal Polynomials. Gordon and Breach, New York (1978)

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Medicaid C CHIP: October monthly applications and eligibility determinations report. Baltimore (2013)

Congdon, P.: Estimating population prevalence of psychiatric conditions by small area with applications to analysing outcome and referral variations. Health Place 12, 465–478 (2006)

Cressie, N.: Statistics for Spatial Data. Wiley, New York (1993)

Cunningham, P.: Health policy brief. Unpublished manuscript (2014)

Dickson, V.: Medicaid plans struggle to provide mental health services. Modern Healthcare (2015). http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20150704/MAGAZINE/307049979

Elbers, C., Fujii, T., Lanjouw, P., Ozler, B., Yin, W.: Poverty alleviation through geographic targeting: how much does disaggregation help? J. Dev. Econ. 83, 198–213 (2007)

Elbers, C., Lanjouw, J., Lanjouw, P.: Micro-level estimation of poverty and inequality. Econometrica 71(1), 355–364 (2003)

Ellis, A., Konrad, T., Thomas, K., Morrissey, J.: County-level estimates of mental health professional supply in the United States. Psychiatr. Serv. 60(10), 1315–1322 (2009)

Frank, R., Goldman, H., Hogan, M.: Medicaid and mental health: be careful what you ask for. Health Aff. 22(1), 101–113 (2003)

Frean, M., Gruber, J., Sommers, B.: Premium subsidies, the mandate, and medicaid expansion: coverage effects of the Affordable Care Act. Unpublished manuscript (2016)

Geweke, J.: Antithetic acceleration of Monte Carlo integration in Bayesian inference. J. Econom. 38(1/2), 73–89 (1988)

Heeringa, S., Wagner, J., Torres, M., Duan, N., Adams, T., Berglund, P.: Sample designs and sampling methods for the collaborative psychiatric epidemiology studies (CPES). Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 13(4), 221–240 (2006)

Hudson, C.: Validation of a model for estimating state and local prevalence of serious mental illness. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 18(4), 251–264 (2009)

Jackson, J., Neighbors, H., Nesse, R., Trierweiler, S., Torres, M.: Methodological innovations in the national survey of American life. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 13(4), 289–298 (2006a)

Jackson, J., Torres, M., Caldwell, C., Neighbors, H., Nesse, R., Taylor, R., Trierweiler, S., Williams, D.: The national survey of American Life: a study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 13(4), 196–207 (2006b)

Kessler, R., Berglund, P., Walters, E., Leaf, P., Iouzis, A., Bruce, M., Friedman, R., Grosser, R., Kennedy, C., Kuehnel, T., Laska, E., Manderscheid, R., Narrow, W., Rosenheck, R., Schneier, M.: A methodology for estimating the 12-month prevalence of serious mental illness. Mental Health, United States, 1998. US Department of Health and Human Services, SAMHSA (1998)

Kessler, R., Chiu, W.T., Demier, O., Walters, E.: Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62, 617–627 (2005)

Konrad, T., Ellis, A., Thomas, K., Holzer, C., Morrissey, J.: County-level estimates of need for mental health professionals in the United States. Psychiatr. Serv. 60(10), 1307–1314 (2009)

LaForest, M., Stern, S.: Translation of correlation in latent variables into correlation in observed variables. Unpublished manuscript (2016a)

LaForest, M., Stern, S.: Wald test for common mean probabilities across communities. Unpublished manuscript (2016b)

Lavy, V., Palumbo, M., Stern, S.: Simulation of multinomial probit probabilities and imputation. In: Fomby, T., Carter Hill, R. (eds.) Advances in Econometrics. JAI Press, Stamford (1998)

Leroux, B., Lei, X., Breslow, N.: Estimation of disease rates in small areas: a new mixed model for spatial dependence. In: Elizabeth Halloran, M., Berry, D. (eds.) Statistical Models in Epidemiology, the Environment, and Clinical Trials. Springer, New York (1999)

Malec, D., Müller, P.: Pushing the limits of contemporary statistics: contributions in honor of Jayanta K. Ghosh. In: A Bayesian Semi-parametric Model for Small Area Estimation, vol. 3, pp. 223–236 (2008)

McAlpine, D., Mechanic, D.: Utilization of specialty mental health care among persons with severe mental illness: the roles of demographics, need, insurance, and risk. Health Serv. Res. 35(1), 277–292 (2000)

Mechanic, D.: Is the prevalence of mental disorders a good measure of the need for services? Health Aff. 22(5), 8–20 (2003)

Merwin, E., Hinton, I., Dembling, B., Stern, S.: Shortages of rural mental health professionals. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 27(1), 42–51 (2003)

Miller, J., Maududi N.: NASMHPD Resource Management Guide: Impacts of Affordable Care Act on Coverage for Uninsured People with Behavioral Health Conditions. National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (2013)

Morrissey, J., Domino, M., Cuddeback, G.: Expedited medicaid enrollment, mental health service use, and criminal recidivism among released prisoners with severe mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 67, 842–849 (2016)

Muntaner, C., Eaton, W., Diala, C., Kessler, R., Sorlie, P.: Social class, assets, organizational control and the prevalence of common groups of psychiatric disorders. Soc. Sci. Med. 47(12), 2043–2053 (1998)

Narrow, W., Rae, D., Robins, L., Regier, D.: Revised prevalence estimates of mental disorders in the united states: using a clinical significance criterion to reconcile 2 surveys’ estimates. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 59, 115–123 (2002)

Opsomer, J., Claeskens, G., Ranalli, M., Kauermann, G., Breidt, F.: Non-parametric small area estimation using penalized spline regression. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 70(1), 265–286 (2008)

Pearlman, S.: The patient protection and Affordable Care Act: impact on mental health services demand and provider availability. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 19(6), 327–334 (2013)

Pennell, B.-E., Bowers, A., Carr, D., Chardoul, S., Cheung, G.-q., Dinkelmann, K., Gebler, N., Hansen, S.E., Pennell, S., Torres, M.: The development and implementation of the national comorbidity survey replication, the national survey of American life, and the national Latino and Asian American survey. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 13(4), 241–269 (2006)

Perloff, J., Kletke, P., Fossett, J., Banks, S.: Medicaid participation among urban primary care physicians. Med. Care 35(2), 142–157 (1997)

Prasad, N., Rao, J.: On robust small area estimation using a simple random effects model. Surv. Methodol. 25, 67–72 (1999)

Robins, L., Regier, D.: Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. The Free Press, New York (1991)

Sommers, B., Rick, K., Kenneth, F., Rosa, P., Karyn, S., Sherry, G.: Understanding participation rates in medicaid: implications for the Affordable Care Act. ASPE Issue Brief (2012)

Stern, S.: Semiparametric estimates of the supply and demand effects of disability on labor force participation. J. Econom. 71(1–2), 49–70 (1992a)

Stern, S.: A method for smoothing simulated moments of discrete probabilities in multinomial probit models. Econometrica 60(4), 943–952 (1992b)

Stern, S.: Estimating local prevalence of mental health problems. Health Serv. Outcomes Res. Methods 14, 109–155 (2014)

Stern, S., Merwin, E., Hauenstein, E., Hinton, I., Rovnyak, V., Wilson, M., Williams, I., Mahone, I.: The effects of rurality on mental and physical health. Health Serv. Outcomes Res. Methods 10(1), 33–66 (2010)

Tarozzi, A., Deaton, A.: using census and survey data to estimate poverty and inequality for small areas. Rev. Econ. Stat. 91(4), 773–792 (2009)

Thomas, K., Ellis, A., Konrad, T., Holzer, C., Morrissey, J.: County-level estimates of mental health professional shortage in the united states. Psychiatr. Serv. 60(10), 1323–1328 (2009)

Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services: Bridging the mental health coverage gap in Virginia. http://www.dmas.virginia.gov/Content_atchs/gap/FINALFact Sheet.pdf (2014)

Wanchek, T., Mcgarvey, E., Leon-Verdin, M., Bonnie, R.: The Effect of community mental health services on hospitalization rates in Virginia. Psychiatr. Serv. 62(2), 194–199 (2011)

Wang, P., Lane, M., Olfson, M., Pincus, H., Wells, K., Kessler, R.: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62(6), 629–640 (2005)

Wells, K., Sturm, R., Burnam, A.: National Survey of Alcohol, Drug, and Mental Health Problems [Healthcare for Communities], 2000–2001 [Computer file]. ICPSR version. University of California, Los Angeles, Health Services Research Center [producer], 2004, Los Angeles, CA. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], Ann Arbor, MI (2005)

Wooldridge, J.: Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. MIT Press, Cambridge (2002)

Zuvekas, S.: National estimates of health insurance coverage, mental health utilization, and spending for low-income individuals. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD (2009). http://www.ahrq.gov/policymakers/health-initiatives/meps/lowinc/lowinc.html

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Elizabeth Merwin for helpful comments and Stuart Shuhit for excellent help with one of the figures. All errors are ours.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

In the interest of “fair advertising” we report that Stern was a member of the Board of Directors of one of the Virginia CSBs (Region Ten) for 9 years and its chairman for two of those years.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

This appendix explains how to interpret the probit estimates in Table 1 in terms of a simpler example. Consider a model,

We can write Eq. (2) as

where

Obviously, endogeneity leads to asymptotically biased estimates of (β, α). But, if one is comfortable assuming that \( \tilde{u}_{i} \sim iidN\left( {0,1} \right) \), then the (biased) probit estimator still provides a good estimator of \( E\left( {y_{i} | e_{i} ,X_{i} } \right) \). Stern (1992a, 1992b), among others, provides suggestive evidence that binary discrete choice models are somewhat robust to distributional assumptions.

1.1 Appendix 2

The map in Fig. 8 was taken from http://www.dbhds.virginia.gov/individuals-and-families/community-services-boards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Johnson, W.C., LaForest, M., Lissenden, B. et al. Variation in mental illness and provision of public mental health services. Health Serv Outcomes Res Method 17, 1–30 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10742-016-0167-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10742-016-0167-3