Abstract

I present an improved methodology for estimating local prevalence rates using classical econometric methods. I provide information on the variation within national mental health surveys associated with ICD versus DSM coding. Conditional on the validity of national survey responses, I estimate precise and statistically significant models associated with binary measures of mental health diagnoses. I also present estimates from polychotomous discrete choice allowing for covariance in errors. Focusing on binary discrete measures, empirical results from NCS-R and NSADMHP are qualitatively similar though very different from NHIS. I speculate that, to a significant degree, this occurs because both NCS-R and NSADMHP rely on popular screening tools to mechanically diagnosis sample participants, while NHIS relies on self-diagnosis. I also discuss the effects on local prevalence estimates caused by unobserved community-specific effects. Finally, I use the results to make policy statements about the provision of public mental health services in central Virginia; the results document a severe shortage of services for people who are unlikely to be able to afford services in the private market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Later, in Sect. 5.4, I perform an empirical exercise using data from central Virginia.

Lutterman (2011) shows similar results across the United States.

Regier et al. (1998) argues that diagnostic counts by themselves are not that useful for mental health planning purposes.

Note that there is some overlap (e.g., New York).

Konrad et al. (2009) goes a few steps further in constructing estimates of discrepancies between supply and demand for mental health services. In particular, it estimates individual demand for mental health services conditional on observed demographic and mental health characteristics to complete the task of estimating demand for services. Then, Ellis et al. (2009) estimates supply of mental health providers disaggregated by type of provider and geography.

Later, we include a Strata/PSU-specific error term causing correlation across observations.

Throughout the paper, I assume that errors are normally distributed. For the single outcome case in Eqs. (1) and (2), one might consider replacing a normality assumption with a logit assumption. In a different context, Stern (1996) provides evidence that estimation results are insensitive to the distributional assumption. This result is consistent with, for example, Cox (1970) and Maddala (1983). However, the logit does not generalize as nicely as probit for multivariate outcomes.

Kessler et al. (1998) does not need to simulate any missing values because they limit the set of explanatory variables to a small set available in Census data.

There may be some individual observations in the local data set with missing values. For such observations, one can treat the individual missing variables as part of \(Z_{2i}\).

LPS allows for cases (1), (2), and (3) but not (4) and (5).

See, for example, Maddala (1983) for a discussion of each of these cases.

Weissman et al. (1991) finds that lifetime prevalence rates for affective disorders decline with age. Helzer et al. (1991) finds similar results for alcohol abuse. This age effect on lifetime prevalence is mechanically impossible as a true age effect; however it could be a cohort effect. See, for example, Grella (2009) for a thoughtful discussion of cohort effects with respect to substance abuse.

The variables used are listed in Sect. 8.1.

This may occur because the question used to identify anxiety is “Frequently Depressed or Anxious,” thus probably including some respondents with depression as suffering from anxiety.

Variable names are written in a different font to distinguish them from the English usage of the same word.

Health better than fair aggregates health good and health excellent.

I classify someone as having a functional limitiation if they answer affirmatively to being limited in any one of the following ways: (a) lifting; (b) climbing steps; (c) walking; (d) standing; (e) bending; (f) reaching; (g) using fingers; or (h) writing.

The NCS-R is part of a consortium of surveys, the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES). The CPES merges data from the NCS-R, the National Survey of American Life, and the National Latino and Asian American Study. See Alegria et al. (2006a, b), Heeringa et al. (2006), Jackson et al. (2006a, b), and Pennell et al. (2006) for more detail.

The ICD is published by the WHO and used internationally to classify diseases including mental health disorders. The DSM is published by the American Psychiatric Association and prefered over the ICD by psychiatrists, especially in the U.S., in order to diagnose patients with mental disorders. See Andrews and Slade (1999) or American Psychological Association (2009) for more information.

I classify someone as having a functional limitiation if they answer affirmatively to any one of the three questions: (a) Have you been limited in past 3 months due to a health problem (Variable SC10_1H); (b) Do you have a physical disability (Variable SC10_4E); or (c) Do you have a condition that substantially limits physical activity (Variable SC10_4F).

See, for example, Alexandre and French (2001) for a discussion of the relationship between religiosity and mental health.

The college variable is constructed as the union of four separate questions of highest grade attained. While there are a few cases where there are inconsistencies across these four measures, they are not the cause of the unusually high proportion of college graduates.

See Sect. 8.3 for a list of the NSADMHP question #s that define having a mental health problem.

Kessler et al. (2002) suggests other similar measures based on DSM.

The equivalent curve conditioning on MCS-12 would be relatively flat given the small difference in MCS-12 distributions.

Also, there is a small number of observations for which income is missing.

A community is typically a collection of counties in close geographic proximity.

The correlation is across individuals within the same family.

Community characteristics come from merging with the Area Resources File and are county specific.

Prasad and Rao (1999) and Opsomer et al. (2008) treat the community effects as random effects. Stern et al. (2010) treats them as fixed effects because (a) it has a large number of observations per community and (b) it does not have to assume the community effects are independent of observed community characteristics by treating them as fixed effects. Congdon (2009) looks at the effect of community characteristics on the prevalence of heart disease and finds that community characteristics are important in explaining some of the geographical variation in prevalence. However, Stern et al. (2010) finds important community-specific fixed effects even after controlling for a larger set of community characteristics than were found in Congdon (2009).

The NCR and NSADMHP have similar types of information, although it is somewhat harder to use in NSADMHP.

In theory, alternatively one could treat the effects as fixed. However, given the nonlinearity of the model, the fixed effects can not be differenced out except in very special cases (Chamberlain 1980)..

Dysthymia is reported in the ECA but not by Robins and Regier (1991) in a way that is comparable to the other numbers in the table.

The NHIS reports separate rates for drug and alcohol abuse, but I aggregate them for this analysis.

Anthony and Helzer (1991, Table 6-17) finds important interactions between age and gender for substance abuse. I do not include such an interaction in my analysis.

Keith et al. (1991) finds similar insignificant results for the effect of education on schizophrenia. It argues that the correlation between age and education explains the lack of effect. However, I control for age and still get statistically insignificant results.

For example, Wells et al. (1989), Katon and Sullivan (1990), and Watanabe et al. (2008) document high comorbidity rates between physical and mental health problems. Among others, Ford et al. (1998), Glassman and Shapiro (1998), Musselman et al. (1998), and Frasure-Smith and Lesperance (2005) provide support for causation going in both directions.

There are only 9 degrees of freedom because the last interval had no observations.

While the figure might lead one to believe that one cannot reject \(H_{0}:Q_{1}=Q_{2}=Q_{3}\) (where \(Q_{j}\) is the \(j\)th quantile), such a conclusion would be incorrect because it ignores the positive correlation among the three quantile estimates. In fact, almost all of the movement across realizations of the quantile estimates are just vertical shifts of all three together.

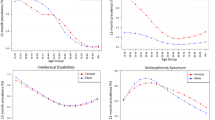

Figures for diagnoses other than anxiety and depression are available from the author.

In a typical multivariate probit model, one would have to restrict all of the diagonal terms of the covariance matrix to be one for identification purposes. Here, the identifying restrictions are that the first diagonal term is one and the psu/strata standard deviation is common across all diagnoses.

Also, in Fig. 10, it is not obvious that the curves stochastically dominate each other in the way one would expect. However, integration of the displayed density functions results in three curves that do stochastically dominate each other in the expected order.

I do not use a Strata/PSU standard deviation for the NSADMHP because the sample already provides for some important geographic dispersion.

The confidence region for health poor looks like a line segment because the NSADMHP estimate is estimated very precisely.

Confidence regions are ellipses because the two data sets provide independent estimates with different standard errors.

In fact, since MHI-5 is a function of underlying answers about the existence of mental health problems, it is very unlikely that an MHI-5 score would be reported without the inputs to the MHI-5 score also being reported.

In the interest of fair advertising, I should point out that I was on the board of directors of the Region Ten CSB when I wrote this paper.

References

Alderman, H., Babita, H.M., Demombynes, G., Makhatha, N., Ozler, B.: How low can you go? Combining census and survey data for mapping poverty in South Africa. J. Afr. Econ. 11, 169–200 (2002)

Alegria, M., Jackson, J., Kessler, R., Takeuchi, D.: Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology: Surveys (CPES), 2001–2003 [United States] [Computer file]. ICPSR20240-v4. Institute for Social Research, Survey Research Center [producer], Ann Arbor (2007). Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], Ann Arbor (2008)

Alegria, M., Takeuchi, D., Canino, G., Duan, N., Shrout, P., Meng, X.-L., Vega, W., Zane, N., Vila, D., Woo, M., Vera, M., Guarnaccia, Peter, Aguilar-gaxiola, Sergio, Sue, S., Escobar, J., Lin, K., Gong, F.: Considering context, place and culture: the National Latino and Asian American Study. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 13(4), 208–220 (2006a)

Alegria, M., Vila, D., Woo, M., Canino, G., Takeuchi, David, Vera, Mildred, Febo, Vivian, Guarnaccia, Peter, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Sergio, Shrout, Patrick: Cultural relevance and equivalence in the NLAAS instrument: integrating etic and mmic in the development of cross-cultural measures for a psychiatric epidemiology and services study of Latinos. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 13(4), 270–288 (2006b)

Alexandre, P., French, M.: Labor supply of poor residents in metropolitan Miami, Florida: the role of depression and the co-morbid effects of substance use. J. Ment. Health Policy Econ. 4, 161–173 (2001)

American Psychological Association: ICD vs. DSM. Monit. Psychol. 40(9), 63 (2009)

Andrews, G., Slade, T.: The classification of anxiety disorders in ICD-10 and DSM-IV: a concordance analysis. Psychopathology 35, 100–106 (2002)

Andrews, Gavin, Slade, Tim: Classification in psychiatry: ICD-10 vs DSM-IV. Br. J. Psychiatry. 174, 3–5 (1999)

Anthony, J., Helzer, J.: Syndromes of drug abuse and dependence. In: Robins, L., Regier, D. (eds.) Psychiatric Disorders in America. The Free Press, New York (1991)

Aoun, S., Pennebaker, D., Wood, C.: Assessing population need for mental health care: a review of approaches and predictors. Ment. Health Serv. Res. 6(1), 33–46 (2004)

Baldwin, M.: Explaining the differences in employment outcomes between persons with and without mental disorders. Unpublished manuscript. (2005)

Banerjee, S., Wall, M., Carlin, B.: Frailty modeling for spatially correlated survival data, with application to infant mortality in Minnesota. Biostatistics 4(1), 123–142 (2003)

Blazer, D., Hughes, D., George, L., Swartz, M., Boyer, R.: Generalized anxiety disorder. In: Robins, L., Regier, D. (eds.) Psychiatric Disorders in America. The Free Press, New York (1991)

Borsch-Supan, A., Hajivassiliou, V.: Smooth unbiased multivariate probability simulators for maximum likelihood estimation of limited dependent variable models. J. Econ. 58(3), 347–368 (1993)

Brown, C., Guo, D., Stern, S.: Analysis of the potential cost savings in medicaid for mental health services in Virginia. Unpublished manuscript (2013)

Chamberlain, G.: Analysis of covariance with qualitative data. Rev. Econ. Stud. 47, 225–238 (1980)

Chihara, T.: An Introduction to Orthogonal Polynomials. Gordon and Breach, New York (1978)

Choy, M., Switzer, P., Parsonnet, J.: Estimating disease prevalence using census data. Epidemiol. Infect. 136, 1253–1260 (2008)

Citro, C., Kalton, G.: Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates: Priorities for 2000 and Beyond. National Academy Press, Washington, DC (2000)

Congdon, P.: Estimating population prevalence of psychiatric conditions by small area with applications to analysing outcome and referral variations. Health Place 12, 465–478 (2006)

Congdon, P.: A multilevel model for cardiovascular disease prevalence in the US and its application to micro area prevalence estimates. Int. J. Health Geogr. 8(1), 6 (2009)

Cox, D.: The Analysis of Binary Data. Methuen, London (1970)

Eaton, W., Dryman, A., Weissman, M.: Panic and phobia. In: Robins, L., Regier, D. (eds.) Psychiatric Disorders in America. The Free Press, New York (1991)

Elbers, C., Fujii, T., Lanjouw, P., Ozler, B., Yin, W.: Poverty alleviation through geographic targeting: how much does disaggregation help? J. Dev. Econ. 83, 198–213 (2007)

Elbers, C., Lanjouw, J., Lanjouw, P.: Micro-level estimation of poverty and inequality. Econometrica 71(1), 355–364 (2003)

Ellis, A., Konrad, T., Thomas, K., Morrissey, J.: County-level estimates of mental health professional supply in the United States. Psychiatr. Serv. 60(10), 1315–1322 (2009)

Fleishman, J., Lawrence, W.: Demographic variation in SF-12 scores: true differences or differential item functioning? Med. Care 41(7), 75–86 (2003)

Ford, D., Mead, L., Chang, P., Cooper-Patrick, L., Wang, N., Klag, M.: Depression is a risk factor for coronary artery disease in men: the precursors study. Arch. Intern. Med. 158, 1422–1426 (1998)

Frasure-Smith, N., Lesperance, F.: Depression and coronary heart disease: complex synergism of mind, body, and environment. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 14(1), 39–43 (2005)

Geweke, J.: Efficient simulation from the multivariate normal and Student-t distributions subject to linear constraints, computer science and statistics. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Third Symposium on the Interface, pp. 571–578 (1991)

Ghosh, M., Natarajan, K., Stroud, T., Carlin, B.: Generalized linear models for small-area estimation. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 93, 273–282 (1998)

Ghosh, M., Rao, J.: Small area estimation: an appraisal. Stat. Sci. 9, 55–93 (1994)

Gill, S., Butterworth, P., Rodgers, B., Mackinnon, A.: Validity of the mental health component scale of the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (MCS-12) as measure of common mental disorders in the general population. Psychiatry Res. 152(1), 63–71 (2007)

Glassman, A., Shapiro, P.: Depression and the course of coronary artery disease. Am. J. Psychiatry 155, 4–11 (1998)

Grant, B., Compton, W., Crowley, T., Hasin, D., Helzer, J., Li, T.-K., Rounsaville, B., Volkow, N., Woody, G.: Errors in assessing DSM-IV substance use disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 64(3), 1–5 (2007)

Grella, C.: Older Adults and Co-occuring Disorders. Alcohol and Drug Policy Institute, Sacramento (2009)

Hauenstein, E., Petterson, S., Merwin, E., Rovnyak, V., Heise, B., Wagner, D.: Rurality, gender and mental health treatment. Fam. Community Health 29(3), 169–185 (2006)

Heeringa, S., Wagner, J., Torres, M., Duan, N., Adams, T., Berglund, P.: Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES). Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 13(4), 221–240 (2006)

Helzer, J., Burnam, A., McEvoy, L.: Alcohol abuse and dependence. In: Robins, L., Regier, D. (eds.) Psychiatric Disorders in America. The Free Press, New York (1991)

Hiller, W., Dichtl, G., Hecht, H., Hundt, W., von Zerssen, D.: An empirical comparison of diagnoses and reliabilities in ICD-10 and DSM-III-R. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 242, 209–217 (1993)

Jackson, J., Neighbors, H., Nesse, R., Trierweiler, S., Torres, M.: Methodological innovations in the National Survey of American Life. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 13(4), 289–298 (2006a)

Jackson, J., Torres, M., Caldwell, C., Neighbors, H., Nesse, R., Taylor, R., Trierweiler, S., Williams, D.: The National Survey of American Life: a study of racial, ethnic and eultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 13(4), 196–207 (2006b)

Jarjoura, D., McCord, G., Holzer, C., Champney, T.: Implementing indirect needs-assessment synthetic estimation of the distribution of mentally disabled adults for allocations to Ohio’s Mental Health Board areas. Eval. Program Plan. 16(4), 305–313 (1993)

Katon, W., Sullivan, M.: Depression and chronic medical illness. J. Clin. Psychol. 51, 3–11 (1990)

Keith, S., Regier, D., Rae, D.: Schizophrenic disorders. In: Robins, L., Regier, D. (eds.) Psychiatric Disorders in America. The Free Press, New York (1991)

Kessler, R., Abelson, J., Demier, O., Escobar, J., Gibbon, M., Guyer, M., Howes, M., Jin, R., Vega, W., Walters, E., Wnag, P., Zaslavsky, A., Zheng, H.: Clinical calibration of DSM-IV diagnoses in the World Mental Health (WMH) version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI). Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 13(2), 122–139 (2004)

Kessler, R., Andrews, G., Colpe, L., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D., Normand, S., Walters, E., Zaslavsky, A.: Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 32(6), 959–976 (2002)

Kessler, R., Berglund, P., Bruce, M., Koch, J., Laska, E., Leaf, P., Manderscheid, R., Rosenheck, R., Walters, E., Wang, P.: The prevalence and correlates of untreated serious mental illness. Health Serv. Res. 36(6 Pt 1), 987–1007 (2001)

Kessler, R., Berglund, P., Walters, E., Leaf, P., Louzis, A., Bruce, M., Friedman, R., Grosser, R., Kennedy, C., Kuehnel, T., Laska, E., Manderscheid, R., Narrow, W., Rosenheck, R., Schneier, M.: A methodology for estimating the 12-month prevalence of serious mental illness. In: Mental Health, United States, 1998. US Department of Health and Human Services, SAMHSA (1998)

Kessler, R., Demler, O., Frank, R., Olfson, M., Pincus, H., Walters, E., Wang, P., Wells, K., Zaslavsky, A.: Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 2515–2523 (2005)

Kessler, R., Berglund, P., Zhao, S., Leaf, P., Kouzis, A., Bruce, M., Friedman, R., Grosser, R., Kennedy, C., Kuehnel, T., Laska, E., Manderscheid, R., Narrow, W., Rosenheck, R., Santoni, T., Schneier, M.: The 12-month prevalence and correlates of serious mental illness. In: Manderscheid, R., Sonnenschein, M. (eds.) Mental Health, United States 1996, pp. 59–70. US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC (1996)

Kessler, R., Chiu, W.T., Walters, E.: Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62, 617–627 (2005)

Konrad, T., Ellis, A., Thomas, K., Holzer, C., Morrissey, J.: County-level estimates of need for mental health professionals in the United States. Psychiatr. Serv. 60(10), 1307–1314 (2009)

Lavy, V., Palumbo, M., Stern, S.: Simulation of multinomial probit probabilities and imputation. In: Fomby, T., Carter Hill, R. (eds.) Advances in Econometrics. JAI Press, Greenwich (1998)

Legler, J., Breen, N., Meissner, H., Malec, D., Coyne, Cathy: Predicting patterns of mammography use: a geographic perspective on national needs for intervention research. Health Serv. Res. 37(4), 929–947 (2002)

Leroux, B., Lei, X., Breslow, N.: Estimation of disease rates in small areas: a new mixed model for spatial dependence. In: Halloran, M., Berry, D. (eds.) Statistical Models in Epidemiology, the Environment and Clinical Trials, pp. 135–178. Springer-Verlag, New York (1999)

Little, R.J.A.: Inference with survey weights. J. Off. Stat. 7, 405–424 (1991)

Lutterman, T.: The impact of the state fiscal crisis on state mental health systems (2011). http://www.nri-inc.org/reports_pubs/2011/ImpactOfStateFiscalCrisisOnMentalHealthSytems_Updated_12Feb11_NRI_Study.pdf. Accessed 29 June 2014

Maddala, G.: Limited-Dependent and Qualitative Variables in Econometrics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1983)

Malec, D., Müller, P.: A Bayesian semi-parametric model for small area estimation. In: Pushing the Limits of Contemporary Statistics: Contributions in Honor of Jayanta K. Ghosh., vol. 3, pp. 223–236 (2008)

Malec, D., Sedransk, J., Moriarity, C., LeClere, F.: Small area inference for binary variables in the National Health Interview Survey. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 92, 815–826 (1997)

Mark, T., Buck, J., Dilonardo, J., Coffey, R., Chalk, M.: Medicaid expenditures on behavioral health care. Psychiatr. Serv. 54, 188–194 (2003)

Mechanic, D.: Is the prevalence of mental disorders a good measure of the need for services? Health Aff. 22(5), 8–20 (2003)

Mendez-Luck, C., Hongjian, Y.: Estimating health conditions for small areas: asthma symptom prevalence for state legislative districts. Health Serv. Res. 42(6), 2389–2409 (2007)

Messer, S., Liu, X., Hoge, C., Cowan, D., Engel, C.: Projecting mental disorder prevalence from national surveys to populations-of-interest: an illustration using ECA data and the US Army. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 39, 419–426 (2004)

Moriarty, D., Zack, M., Holt, J., Chapman, D., Safran, M.: Geographic patterns of frequent mental distress: U.S. Adults, 1993/2003. Am. J. Prev. Med. 36(6), 497–505 (2009)

Musselman, D., Evans, D., Nemeroff, C.: The relationship of depression to cardiovascular disease: epidemiology, biology, and treatment. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 55, 580–592 (1998)

Narrow, W., Rae, D., Robins, L., Regier, D.: Revised prevalence estimates of mental disorders in the United States: using a clinical significance criterion to reconcile 2 surveys’ estimates. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 59, 115–123 (2002)

Nelsen, R.: An Introduction to Copulas. Springer-Verlag, New York (1999)

NASMHPD Research Institute: How do SMHAs organize and fund community mental health services: 2010. State Mental Health Agency Profiles System (2010)

Opsomer, J., Claeskens, G., Ranalli, M., Kauermann, G., Breidt, F.: Non-parametric small area estimation using penalized spline regression. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 70(1), 265–286 (2008)

Pennell, B.-E., Bowers, A., Carr, D., Chardoul, S., Cheung, G., Dinkelmann, K., Gebler, N., Hansen, S.E., Pennell, S., Torres, M.: The development and implementation of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, the National Survey of American Life, and the National Latino and Asian American Survey. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 13(4), 241–269 (2006)

Prasad, N., Rao, J.: On robust small area estimation using a simple random effects model. Surv. Methodol. 25, 67–72 (1999)

Rao, J.: Some recent advances in model-based small area estimation. Surv. Methodol. 25, 175–186 (1999)

Regier, D., Kaelber, C., Rae, D., Farmer, A., Knauper, B., Kessler, R., Norquist, G.: Limitations of diagnostic criteria and assessment instruments for mental disorders: implications for research and policy. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 55, 109–115 (1998)

Robins, L., Regier, D.: Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemioligic Catchment Area Study. The Free Press, New York (1991)

Rounsaville, B.: Experience with ICD-10/DSM-IV substance use disorders. Psychopathology 35, 82–88 (2002)

Stern, S.: Semiparametric estimates of the supply and demand effects of disability on labor force participation. J. Econ. 71(1–2), 49–70 (1996)

Stern, S.: Simulation-based estimation. J. Econ. Lit. 35(4), 2006–2039 (1997)

Stern, S., Merwin, E., Hauenstein, E., Hinton, I., Rovnyak, V., Wilson, M., Williams, I., Mahone, I.: The effects of rurality on mental and physical health. Health Serv. Outcomes Res. Methodol. 10(1), 33–66 (2010)

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Results from the 2002 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. NHSDA Series H-22, DHHS Publication No. SMA 03–3836. Office of Applied Studies, Rockville (2003)

Tarozzi, A., Deaton, A.: Using census and survey data to estimate poverty and inequality for small areas. Rev. Econ. Stat. 91, 773–792 (2009)

Twigg, L., Moon, G., Jones, K.: Predicting small-area health-related behaviour: a comparison of smoking and drinking indicators. Soc. Sci. Med. 50, 1109–1120 (2000)

Virginia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services (2010). http://www.dbhds.virginia.gov/SVC-CSBs.asp. Accessed 29 June 2014

Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services: Statistical Record of the Virginia Medicaid Program and Other Indigent Health Care Programs, FY 2006 Edition (2006). http://www.dmas.virginia.gov/downloads/Stats_06/OVEXPEND-06.pdf. Accessed 29 June 2014

Wang, P., Demler, O., Kessler, R.: Adequacy of treatment for serious mental illness in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 92(1), 92–98 (2002)

Wang, P., Lane, M., Olfson, M., Pincus, H., Wells, K., Kessler, R.: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62(6), 629–640 (2005)

Watanabe, N., Stewart, R., Jenkins, R., Bhugra, D., Furukawa, T.: The epidemiology of chronic fatigue, physical illness, and symptoms of common mental disorders: a cross-sectional survey from the second British National Survey of Psychiatric Morbidity. J. Psychosom. Res. 64(4), 357–362 (2008)

Weissman, M., Bruce, M., Leaf, P., Florio, L., Holzer, C.: Affective disorders. In: Robins, L., Regier, D. (eds.) Psychiatric Disorders in America. The Free Press, New York (1991)

Wells, K., Stewart, A., Hays, R., Burnam, A., Rogers, W., Daniels, M., Berry, S., Greenfield, S., Ware, J.: The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the medical outcomes study. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 262(7), 914–919 (1989)

Wells, K., Sturm, R., Burnam, A.: National Survey of Alcohol, Drug, and Mental Health Problems [Healthcare for Communities], 2000–2001 [Computer file]. ICPSR version. University of California, Los Angeles, Health Services Research Center [producer], Los Angeles (2004). Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], Ann Arbor (2005)

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dori Stern and Yiyi Zhou for excellent research assistance, Ivora Hinton, Caruso Brown, Ted Lutterman, and Summer Durrant for help with data, Deborah Stanford for help with manuscript preparation, the Bankard Fund at the University of Virginia for financial support, and Beth Merwin and seminar participants at UVA, NYU, the Region Ten Community Services Board, and AHRQ for valuable comments. All remaining errors are mine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: NHIS (1995) mental health questions

See Table 23.

Appendix 2: NCS-R mental health questions

See Table 24.

Appendix 3: NSADMHP mental health questions

See Table 25.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stern, S. Estimating local prevalence of mental health problems. Health Serv Outcomes Res Method 14, 109–155 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10742-014-0120-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10742-014-0120-2