Abstract

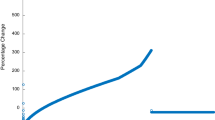

Fairness in access to HE is unarguably a subject of paramount importance. Wherever a student’s secondary school scores are relevant for access to HE, grade inflation practices may jeopardize fair access. Pressures for high grading are common in the context of educational consumerism and competition between schools and students. However, they are not equally distributed across different types of schools, given that they have distinct relationships with the State and the market, and work with distinct populations. Specifically, the schools that are more subject to market pressures (namely private schools) are, in principle at least, the ones with more incentives to inflate their students’ grades. This paper presents an empirical study based on a large, 11 years database on scores in upper secondary education in Portugal, probing for systematic differences in grade inflation practices by four types of schools: public schools, government-dependent private schools, independent (fee-paying) private schools, and specially funded public schools in disadvantaged areas (TEIP schools). More than 3 million valid cases were analysed. Our results clearly show that independent private schools inflate their students’ scores when compared to the other types of schools. They also show that this discrepancy is higher where scores matter most in competition for HE access. This means that—usually wealthier—students from private independent schools benefit from an unfair advantage in the competition for the scarce places available in public higher education. We conclude discussing possible solutions to deal with such an important issue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

At this point, an important methodological issue needs to be addressed. It refers to the use of significance tests with population data. We acknowledge that there is a long-standing, unsettled debate about this (see, for example, Blalock 1972; Cowger 1984; Rubin 1985). While it is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss this matter in detail, the debate can be summarised as revolving around two competing perspectives. At its core, one argues that significance tests are inferential procedures used to rule out sampling error. When population data is available there is no sampling error. Therefore, significance tests are pointless and meaningless in these situations (Cowger 1984). The other view concurs that such tests are devoid of meaning when the goal is simply to describe variations between subpopulations; however they are deemed necessary when one seeks to produce causal, theoretical inferences (Blalock 1972; Rubin 1985). In this debate, we tend to agree with the first perspective. Also, we are well aware that significance testing as usually applied and interpreted, even in studies dealing only with samples, is subject to contention (e.g., McCloskey and Zilliak 1996; Zilliak and McCloskey 2004). In fact, Null Hypothesis Significance Testing, when interpreted correctly, tell us the probability of observing sample statistics when that sample comes from a population where the null hypothesis is true, i.e., from a population in which there are no differences or associations between groups or variables (Cohen 1992; Thompson 2006). Therefore, some authors argue that it is just not useful to test for the null hypothesis when you already know if the null is true and, more importantly, when you know the extent of the differences between groups or associations between variables. We agree with this perspective. However, we acknowledge that the matter is unresolved. Therefore, we also provide here significance tests' results.

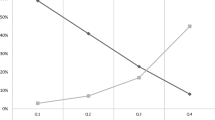

Although the usefulness of doing statistical significance testing on population data is controversial, as discussed in the previous footnote, we have conducted Analysis of Variance (ANOVAs) for each one of the 20 classes of scores in national exams (the rows in Tables 3, 4 or the x axis in the graphs). Regarding the data presented in Table 3 (and Fig. 1), the differences between the three types of schools yielded statistical significance in all classes, with the first class (0–0.99) reaching a p value under 0.05 and all the others classes a p value under 0.001. Post hoc tests (Tukey HSD) revealed differences between independent private schools and government-dependent private schools in the first class, and between all 3 types of schools in all other classes, with the exception of the 7th, 8th, and 9th classes, where the difference between public and dependent-private schools did not reach statistical significance. As observed in Fig. 1 (or Table 3), that is the point where the two lines intercept and cross each other. Regarding the data presented in Table 4 (and Fig. 2), the differences between the four types of schools yielded statistical significance in all classes but the first (0–0.99), with a p value under 0,01. Post hoc tests (Tukey HSD) revealed differences between independent private schools and the rest throughout the score range. Also, from the class 10–10.99 onwards, post hoc tests revealed differences between government dependent private and public schools. Finally, post hoc tests show that TEIP schools do have a more irregular pattern.

References

Allen, J. (2005). Grades as valid measures of academic achievement of classroom learning. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 78(5), 218–223.

Almeida, L., Marinho-Araujo, C. M., Amaral, A., & Dias, D. (2012). Democratização do acesso e do sucesso no ensino superior: Uma reflexão a partir das realidades de Portugal e do Brasil. Avaliação: Revista da Avaliação da Educação Superior, 17(03), 899–920.

Amaral, A., & Magalhães, A. (2009). Between institutional competition and the search for equality of opportunities: Access of mature students. Higher Education Policy, 22(4), 505–521.

Avram, S., & Dronkers, J. (2012). Social class dimensions in the selection of private schools a cross-national analysis using PISA. In H. Ullrich & S. Strunck (Eds.), Private Schulen in Deutschland (pp. 201–223). Berlin: Springer.

Ball, S. (2003). Class strategies and the education market: The middle classes and social advantage. London: Routledge.

Ball, S. J. (2009). Privatising education, privatising education policy, privatising educational research: Network governance and the ‘competition state’. Journal of Education Policy, 24(1), 83–99.

Barroso, J. (2003). Organização e regulação dos ensinos básico e secundário, em Portugal: Sentidos de uma evolução. Educação e Sociedade, 24(82), 63–92.

Blalock, M. (1972). Social statistics. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Brennan, J., & Naidoo, R. (2008). Higher education and the achievement (and/or prevention) of equity and social justice. Higher Education, 56(3), 287–302.

Brighouse, H. (2008). Grade inflation and grade variation:What’s all the fuss about? In L. H. Hunt (Ed.), Grade inflation: Academic standards in higher education (pp. 73–92). New York: SUNY Press.

Brinbaum, Y., & Guégnard, C. (2013). Choices and enrollments in French secondary and higher education: Repercussions for second-generation immigrants. Comparative Education Review, 57(3), 481–502.

Brunori, P., Peragine, V., & Serlenga, L. (2012). Fairness in education: The Italian university before and after the reform. Economics of Education Review, 31(5), 764–777.

Buisson-Fenet, H., & Draelants, H. (2013). School-linking processes: Describing and explaining their role in the social closure of French elite education. Higher Education, 66, 39–57.

Causa, O., & Johansson, A. (2010). Intergenerational social mobility in OECD countries. OECD Economic Studies, 2010, 1–44.

Cohen, J. (1992). Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1, 98–101.

Cowger, C. D. (1984). Statistical significance tests: Scientific ritualism or scientific method? Social Service Review, 58(3), 358–372.

Dale, R., & Robertson, S. (2009). Globalisation and Europeanisation in education. Oxford: ERIC.

Duru, M. (1986). Notation et orientation: Quelle cohérence, quelles conséquences? Revue française de pédagogie, 77, 23–37.

Duru-Bellat, M., & Mingat, A. (1988). Le déroulement de la scolarité au collège: le contexte «fait des différences». Revue Française de Sociologie, 29(4), 649–666.

Fonseca, M. P., & Encarnação, S. (2012). O sistema de ensino superior em Portugal em mapas e números. Lisboa: Agência de Avaliação e Acreditação do Ensino Superior.

Frempong, G., Ma, X., & Mensah, J. (2012). Access to postsecondary education: Can schools compensate for socioeconomic disadvantage? Higher Education, 63(1), 19–32.

Grácio, S. (1998). Ensino privado em Portugal: Contributo para uma discussão. Sociologia - Problemas e Práticas, 27, 129–153.

Heitor, M., & Horta, H. (2012). Science and technology in portugal: From late awakening to the challenge of knowledge-integrated communities. In G. Neave & A. Amaral (Eds.), Higher education in Portugal: 1974–2009 (pp. 179–226). Dordrecht: Springer.

Horta, H. (2010). The role of the State in the internationalization of universities in catching-up countries: An analysis of the Portuguese higher education system. Higher Education Policy, 23, 63–81.

Hunt, L. H. (2008). Grade inflation: Academic standards in higher education. Albany: SUNY Press.

Justino, D. (2005). No silêncio somos todos iguais. Lisboa: Gradiva.

Konečný, T., Basl, J., Mysliveček, J., & Simonová, N. (2012). Alternative models of entrance exams and access to higher education: The case of the Czech Republic. Higher Education, 63(2), 219–235.

Leathwood, C. (2004). A critique of institutional inequalities in higher education (or an alternative to hypocrisy for higher educational policy). Theory and Research in Education, 2(1), 31–48.

Liu, A. (2011). Unraveling the myth of meritocracy within the context of US higher education. Higher Education, 62(4), 383–397.

Magalhães, A., Amaral, A., & Tavares, O. (2009). Equity, access and institutional competition. Tertiary Education and Management, 15(1), 35–48.

Marginson, S. (2011). Equity, status and freedom: A note on higher education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 41(1), 23–36.

Martins, P. (2009). Individual teacher incentives, student achievement and grade inflation, IZA discussion paper. Bonn: Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit.

McCloskey, D. N., & Zilliak, S. T. (1996). The standard error of regressions. Journal of Economic Literature, 34, 97–114.

McCowan, T. (2007). Expansion without equity: An analysis of current policy on access to higher education in Brazil. Higher Education, 53(5), 579–598.

McDonald, P., Pini, B., & Mayes, R. (2012). Organizational rhetoric in the prospectuses of elite private schools: Unpacking strategies of persuasion. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 33(1), 1–20.

MEC. (2012). Relatório TEIP 2010/2011. Lisbon: Ministério da Educação e da Ciência.

Mora, J.-G. (1997). Equity in Spanish higher education. Higher Education, 33, 233–249.

Mountford-Zimdars, A., & Sabbagh, D. (2013). Fair access to higher education: A comparative perspective. Comparative Education Review, 57(3), 359–368.

OECD (2008). OECD Reviews of tertiary education: tertiary education for the knowledge society, 1. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2012). Education at a glance 2012: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Portela, M., Areal, N., Sá, C., Alexandre, F., Cerejeira, J., Carvalho, A., et al. (2008). Evaluating student allocation in the Portuguese public higher education system. Higher Education, 56(2), 185–203.

Rahona López, M. (2009). Equality of opportunities in Spanish higher education. Higher Education, 58(3), 285–306.

Rubin, A. (1985). Significance testing with population data. Social Service Review, 59(3), 518–520.

Sadler, D. R. (2009). Indeterminacy in the use of preset criteria for assessment and grading. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(2), 159–179.

Stone, P. (2013). Access to higher education by the luck of the draw. Comparative Education Review, 57(3), 577–599.

Suchaut, B. (2008). “La loterie des notes au bac: Un réexamen de l’arbitraire de la notation des élèves.” Les Documents de Travail de l’IREDU—Institut de Recherche sur l’Education Sociologie et Economie de l’Education. Dijon.

Sultana, R. G. (2011). Lifelong guidance, citizen rights and the state: Reclaiming the social contract. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 39(2), 179–186.

Tavares, O., & Cardoso, S. (2013). Enrolment choices in Portuguese higher education: do students behave as rational consumers? Higher Education, 66, 297–309.

Thompson, B. (2006). Foundations of behavioral statistics: An insight-based approach. New York: The Guildford Press.

Torres, C. A. (2009). Education and neoliberal globalization. New York: Routledge.

Walsh, P. (2010). Does competition among schools encourage grade inflation? Journal of School Choice, 4(2), 149–173.

Wikström, C. (2005). Grade stability in a criterion-referenced grading system: The Swedish example. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 12(2), 125–144.

Wikström, C., & Wikström, M. (2005). Grade inflation and school competition: An empirical analysis based on the Swedish upper secondary schools. Economics of Education Review, 24(3), 309–322.

Wilkinson, R. G., & Pickett, K. (2011). The spirit level. New York: Bloomsbury Press.

Willingham, W. W., Pollack, J. M., & Lewis, C. (2002). Test scores: Accounting for observed differences. Journal of Educational Measurement, 39(1), 1–37.

Woodruff, D. J., & Ziomek, R. L. (2004a). “Differential grading standards among high schools.” ACT Reseach Report Series, 2004–2.

Woodruff, D. J., & Ziomek, R. L. (2004b). “High school grade inflation from 1991 to 2003.” ACT Reseach Report Series, 2004-4.

Zilliak, S. T., & McCloskey, D. N. (2004). Size matters: The standard error of regressions in the American Economic Review. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 33, 527–546.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nata, G., Pereira, M.J. & Neves, T. Unfairness in access to higher education: a 11 year comparison of grade inflation by private and public secondary schools in Portugal. High Educ 68, 851–874 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9748-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9748-7