Abstract

The intricacies of one of the most relevant agribusiness frontiers in the world today—the north of the State of Mato Grosso, in the southern section of the Amazon, Brazil—are considered through a critical examination of place-making. Vast areas of Amazon rainforest and savannah vegetation were converted there, since the 1970s, into places of intensive soybean farming, basically to fulfil exogenous demands for land and agriculture production. The present assessment goes beyond the configuration of new places at the agricultural frontier, and starts with a qualitative intellectual jump: from place-making on the frontier to place-making as an ontological frontier in itself. It means that, instead of merely studying the frontier as a constellation of interconnected places, we examine the politicised genesis of the emerging places and their trajectory under fierce socio-ecological disputes. The consideration of almost five decades of intense historic-geographical change reveals an intriguing dialectics of displacement (of previous socio-ecological systems, particularly affecting squatters and indigenous groups, in order to create opportunities for migrants and companies), replacement (of the majority of disadvantaged farmers and poor migrants, leading to land concentration, widespread financialisation and the decisive influence of transnational corporations) and misplacement (which is the synthesis of displacement and replacement, demonstrated by mounting risks and a pervasive sentiment of maelstrom). Overall, there was nothing inevitable in the process of rural and regional development, but the problems, conflicts and injustices that characterise its turbulent geographical trajectory were all more or less visible from the outset.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction: placing Mato Grosso’s agricultural frontier

The article is a critical reflection upon the production of new places and associated socio-spatial tensions related to the expansion of the agricultural frontier in the State of Mato Grosso, in the centre-north of Brazil and in the geographical core of South America. The paper will review place-making trends in the vast areas of Amazon rainforest and savannah vegetation that were converted, since the 1970s, into intensive farmland and growing urban settlements. As a result, Mato Grosso constitutes now one the world’s fastest expanding hotspots of agribusiness activity and crop export (Deininger and Byerlee 2011). Our starting point here is that the semiotic and material frictions of modern agribusiness in the Amazon cannot be properly understood without reference to place-making; that is, “the set of social, political and material processes by which people iteratively create and recreate the experienced geographies in which they live” (Pierce et al. 2011, p. 54). In the case of Mato Grosso, agribusiness production has certainly been a powerful place-making engine, given that in just a few decades it was transformed from a remote, largely forgotten part of Brazil into one of the most strategic hubs of production and export in the country. The intensification of agribusiness has created both sectoral relations where capital dynamically circulates (even if most of it leaves the region after the harvest) and large-scale socio-spatial interactions across multiple scales and successive agriculture cycles. Especially in the Teles Pires river basinFootnote 1—situated in the north of Mato Grosso, at the transition from savannah to forest ecosystems—the landscape in the rainy season is dominated by the green colour of huge plantation farms. The region is mostly occupied by first- or second-generation farmers, rural workers and commercial partners who now largely depend on the productivity of soybean and on its price in globalised markets. Those are all integral components of a dynamic, but unequal, place-making phenomenon.

However, the modernisation of agribusiness in relation to place-making has not been properly recognised by scholars working on the political-economy of agri-food networks. There is still a need for dedicated examinations of the intensely politicised processes of inclusion and exclusion mediated by the appropriation of the material and immaterial components of the lived reality. In the case of the Teles Pires, a region previously characterised by exuberant natural scenery and numerous indigenous groups has been irreversibly jolted by roads, new towns and (mostly) soybean fields. The transformation of the Teles Pires happened in less than five decades, always resorting to the monochromatic, but powerful, excuse of economic growth at any price. There was a constant promise of rationality, progress and welfare underpinning public policies and government action. To justify the imposition of the new agricultural frontier, the official discourse emphasised that it was ‘no man’s land’, an empty space ready to accept the displacement of existing socionatural processes and their replacement, even if against the wishes of those already living there. Against what were considered rudimentary, excessively simplistic places, an even greater simplification was imposed: develop or die.

Such extraordinary geographical trends challenge conventional analytical approaches and call for novel interpretative procedures. The next pages will try to fill that intellectual gap and demonstrate that the synthesis of this vicious dialectics between displacement–replacement is the resulting pervasiveness of misplacement. This reflexive examination is focused on the most emblematic municipalities in the Teles Pires—namely, Sorriso, Sinop and Lucas do Rio Verde—which were established after the construction of the BR-163 motorway, with a length of 1777 km, to connect Cuiabá, in the State of Mato Grosso, with Santarém in the neighbouring State of Pará. Before that, it is necessary to review the dedicated literature on place-making and then shed light on our (rather unorthodox) conceptual framework.

Place-related literature and novel analytical sensibilities

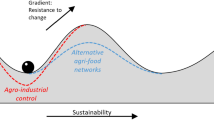

It was already indicated above that place-making is a heuristic analytical category to understand the lived space, but also to uncover the discursive and contextual aspects of the agricultural frontier established in Mato Grosso. New areas of production, such as the Teles Pires river basin, are a locus of intense spatial reworking and relentless experimentation, which stretches from the specific and actually existing to the general and intertemporal. The agricultural frontier is more than just a zone of capitalist transition (cf. Barney 2009); it is a true ‘laboratory’ or ‘smelting’ of space with competing tempos and rival spatial rhythms. Because of its intense activity, agribusiness at the frontier of economic development is an accelerated mechanism of place-making that is reliant on the rapid conversion of abundant territorial resources and on the promise of a better life. The resulting places are still relatively young, in terms of their politico-economic and social-ecological track records, and their ontological novelty encapsulates emerging socio-ecological relations at the intersection between powerful global markets, regional development, widespread disruptions and interpersonal connections. However, it is not enough to meticulously and critically examine the places that form the new agricultural frontier. What is also needed, as an important elements of our analytical approach, is a qualitative intellectual jump from place-making on the frontier to place-making as an ontological frontier in itself. It means that, instead of merely studying the frontier as a constellation of interconnected places, it is important to scrutinise the politicised genesis of the emerging places and their trajectory under socio-ecological disputes.

The nuanced ontological relationships between scales, times and dimensions are normally missed in conventional geographical texts, in which places are simply associated with the local and particular, in contrast with large-scale connections typically related to space. In the tradition of Vidal de la Blache, Fernand Braudel and others, place is taken as a slice, or a portion, of space with specific geographical qualities that are hard to generalise. Schematically speaking, place is the unique, while space is the more general. Such a rigid space-place dichotomy (which replicates other fruitless dichotomies, such as general-particular, anecdotal-historical and nature-society) certainly offers little help regarding the geography of the agribusiness frontier. Fortunately, we can find support in three alternative approaches that, although not necessarily applied to agricultural areas, lay emphasis on the social practices involved in place-making and on the fluid connections between locales, places and other spatial scales (Agnew 2011). First of all, feminist scholars have pointed out that the identities of places are necessarily unfixed, contested and multiple, whereas local experiences are not only localised. Mundane, taken for granted activities, most practiced by women, also play a very important role in the making of places, which happens at the interconnection with wider politico-economic and globalised processes (Dyck 2005). That is particularly the case because domestic and caring labour are essential for the reproduction and stabilisation of capitalist relations of production (Mcdowell 2015). What gives places their specificity is the fact that they are constructed out of myriad social and physical relations spreading through networks and different scales of interaction. While there is a global and globalised sense of places and place-making, the “global is in the local in the very process of the formation of the local” (Massey 1994, p. 120). Consequently, grand narratives about place, and any other spatial formation, exert a highly negative influence, because they obscure the importance of gender, race, caste and age differences and, as a result, lower the possibility for genuine political change (Massey 1993). Instead of that, people’s experiences and the zooming in on individual lives allows for a close look at the particularity and everydayness of place-making and of being-in-place (Lems 2016).

In addition, humanist geographers, also in opposition to pedestrian interpretations, insist that senses and opinions are likewise active agents of place-making. A place is not determined in advance, but is simultaneously performed and represented. Humanist geography underscores social difference, avoiding generalisations and recognising the centrality of place and its multiple forms (Arenas and Geisse 2004). Tuan (1976) emphasises the importance of understanding people’s behaviour, conditions, ideas and feelings in relation to the intricacies of space and place. Such agent-based interpretations are directly concerned with questions about consciousness, experience and intentionality. Places are connected to the core of people’s existence, their practices, feeling and social relations (Bartos 2013). They have both an intimate dimension and a socialising logic (Antonsich 2010). Intentionality is, thus, an emergent relation with the world and not a pre-given condition of experience (Ash and Simpson 2016); by the same token, subjective views of place and space influence conscious or unconscious acts (Schutz 1972). Place-making is necessarily seen here as a relational phenomenon embedded in the activity of politicised, non-territorialised networks in which places are framed (Pierce et al. 2011) and places should be treated relationally in order to better cope with a series of interactions that run ‘into’ and ‘out from’ places, such as climate change, labour movements and trade relations (Darling 2009), but still maintaining a critical engagement with the socio-political ordering of the world, including social, corporate and government organisations (May 1996). Such humanist, and closely related phenomenological, explanations are often intertwined with the arguments of cultural geographers, who contend that the meaning and experience of places also involves cultural questions resulting from a cumulative spiral of signification (Thrift 1983). Individuals have multiple attachments to place and experience it according to their cultural, political and historical circumstances (Pocock 1981). Places are multifaceted cultural constructions, just as culture is the medium through which socio-spatial changes are experienced, contested and constituted (Cosgrove and Jackson 1987).

Another (third) important voice in this debate about the ontological foundations of place-making has come from radical geographers underscoring the damaging repercussions of class struggle and related forms of socio-ecological exploitation that are place-based. According to this group of authors, class struggle is directly associated with the politics of place-making and with processes of place homogenisation and differentiation. Harvey (2006) points out that places, and other spatial arrangements, such as landscape and territory, assume specific attributes under the capitalist mode of production, given that the control of place is essential to secure command over material commodity exchanges and authority over the workforce (for instance, with the threat of moving jobs to other locations). Uneven development, which is a central feature of the capitalist economy, is to a great extent a product of place-specific outcomes of the process of class struggle (Das 2012). The complexity and variegatedness of place-making in a capitalist society thus requires conceptions of abstract, structural power complemented by the politics of everyday life, which should account for interpersonal relations, networks of subjectivity and socio-economic systems (Bridge 1997; Ioris 2013). One the one hand, the contradictions between market rules and social relations around place are typically suppressed by authoritarian forces that try to minimise and forcefully repress opposition and discontent (Thornton 2010). On the other, the politicisation of place, as much as the dynamics of social change and the possibilities of political emancipation, are important elements of critical scholarship (Swyngedouw 1999). From this radical geography perspective, disputes over statecraft under capitalism are also shaped by the politics of place and related to the possibilities for political practice by creating particular terrains of conflict, determining the terms of access and influencing subjective experiences of political life (Chouinard 1990).

The convergence of these three streams of geographical thought—namely, feminist, humanist and class-based—can surely inform our conceptual framework for the examination of place-making at the agribusiness frontier. Moreover, although place is connected to the construction of political thinking and the production of knowledge, questions about place-making cannot be resolved at the level of theory only (Dirlik 1999). The frontiers of intensive agriculture expansion (agribusiness) in the world today are less about business (as a purely economic result) and even less about agro (as food), because the most central interest is the immanent existence of the frontier itself (as a capitalist world order in the making). The agribusiness frontier constitutes a highly idiosyncratic ‘space–time envelope’ (cf. Massey 1994) in which the being and the becoming are still actively struggling. In the case of the Teles Pires, the frontier was the result of government plans, accumulated socio-economic demands for land (in other parts of the country) and the search for new money-making opportunities. New places were created through a curious unfolding of forthcoming and opposing forces, which combined the drive to conquest and the impetus to abandon what was already sufficiently explored. While the frontier has produced novel social actors, it has nurtured by the rhetorical fabrication of an outside world inhabited by those who can be friends but are more often seen as foes (i.e. its ontological basis also depends on the interference of others within and outside, cf. Qian et al. 2012). For all these reasons, place-making at the frontier is not just the manufacturing of new spatial arrangements; it also opens up the possibility to better interpret places as ontological frontiers.

In addition to points highlighted in the brief review above, the uniqueness of the agribusiness frontier in the southern Amazon requires the help of bespoke intellectual devices capable of scrutinising the multiple mediations, suspended certainties and disputed rationales related to the production of places. Luckily, the examination of the intricate ontological questions related to place-making in Mato Grosso can find unexpected assistance in the ideas of a ‘very special geographer’: the recently deceased poet Manoel de Barros (1916–2014), regarded by the critics as one of the best authors of contemporary Brazilian literature. The need to liberate the reality from its pre-arranged place-based configurations, and recreate the world, permeates Manoel’s long and incredibly original artistic construction. Manoel left a vast artistic production full of incredible images and lavish verses that basically deal with what is considered secondary or irrelevant (e.g. encounters with stones, birds, insects, horses, organic and decaying matter, the habits of scattered rural families, etc.). From the micro and insignificant the poet constructs an argument about some of the most universal and unending questions of human existence. He understood that ‘Things don’t want to be seen by reasonable people’ [As coisas não querem ser vistas por pessoas razoáveis] (Barros 2013, p. 278) and also that ‘That which goes nowhere has a great importance’ [As coisas que não levam a nada têm grande importância] (Barros 2013, p. 135). It is a fortunate coincidence that Manoel was born in Mato Grosso and spent his early years on the shores of the Paraguay River, where distances were immense and time seemed to move very slowly. In his words, his family lived “in a place where there was nothing (…) and we had to invent” the world; “invention was required to enlarge the world” and “disturb” the existing, normal meaning of things.

Manoel’s fundamental ontological proposition was that Mato Grosso had yet to be ‘invented’ in order to decipher still unarticulated truths. Manoel realised, since his childhood, that the immensity of Mato Grosso was incomplete and, consequently, his world had still to be created, that is, the intense and sophisticated exchanges with nature and the small number of inhabitants needed to be complemented with broader social intercourses and connections with wider Brazilian and international society. A new reality needed to be invented was not only to be true, but because it was necessary to unlock the deep structures of the existing world. Central to Manoel’s ontology is the difference between ‘invention’ and ‘lie’, in other words, the realisation that invention is diametrically in opposition to falsehood. In what was probably the only public interview ever given by Manoel de Barros – turned into the documentary ‘Only Ten Percent is Lying’ [Só Dez por Cento é Mentira] by Pedro Cezar, released in 2010—Footnote 2 Manoel claims that only 10 % of his argument is untrue and 90 % is invented [Tenho uma confissão a fazer: noventa por cento do que escrevo é invenção. Só dez por cento é mentira]. In his verses he already states that ‘all that I didn’t invent is false’ [Tudo que não invento é falso] (Barros 2013, p. 319). But, crucially, the new reality needs to maintain the organic ontology that rightly encompasses everything, including organisms, people, stones, fluids, landscapes and unsaid sensations. In his highly original poetry, ‘The trees commence me’ [As árvores me começam], cf. Barros 2013, p. 311]. Inspired by Manoel’s provocation about the world to be invented, we will demonstrate the troubling trajectory of places at the Teles Pires frontier and how place-making there has unfolded through a disconcerting dialectics of displacement–replacement–misplacement.

Place-making through displacement (1940s–early 1980s)

In stark contrast to the supposed spirit of ‘democracy and egalitarianism’ famously associated with the American West by Frederick Jackson Turner,Footnote 3 the agricultural frontier in Mato Grosso was initially based on a widespread practice of displacement. For many generations of Brazilians, the north of Mato Grosso was a faraway place, a universe apart and homeland mainly to secluded First Nation peoples. That began to change in the first decades of the twentieth century due to ideological calls for modernisation, progress and integration of areas considered wasteland. The federal administration launched the March towards the West in 1937 and the Roncador-Xingu expedition in 1943 to fill the geographical voids still uncomfortably visible on national maps (Villas Bôas and Villas Bôas 1994). But the integrationist project didn’t include the locals and their socio-ecology; on the contrary, the rest the country fell over the region bringing back the spectres of Alexander, Alaric and Pizarro. New places started to be forged out of the remnants of the cultures, values and cultures of those who used to live in the region (indigenous groups and squatter peasants) and also out of the destruction of socio-ecological communities. The occupation of the north of Mato Grosso, financed and stimulated by state agencies, happened through the widespread and systematic grabbing [grilagem] of indigenous land, which amounted to an “authentic ethnocide and genocide” of many tribes (Oliveira 2005, p. 84). In tandem with initiatives undertaken by the national government, the state (i.e. provincial) administration systematically sold large tracts of land at very low cost to property speculators, certainly without much interest in exploring the areas. Vast state-owned areas, with hundreds of thousands of hectares—described in Portuguese as glebas—were easily transferred to new owners by corrupt officials, who typically expelled the local residents, used the areas as collateral for bank loans or re-sold them to colonisation firms (Moreno 2007). The fact that these glebas were demarcated from distant offices without any fieldwork opened the door to major imprecision, inadequate property boundaries and monumental fraud.

The decisive phase of spatial transformation came with the resolve of the ruling military between 1964 and 1985 to force agriculture development upon the remote corners of the Centre-West region. Three National Integration Plans and other similar programmes, with international funding, were introduced in the 1970s. The State of Mato Grosso was actually considered the “paradise of private colonisation” projects (Oliveira 1989, p. 106), which since 1974 replaced the initial focus on public farming schemes (Santos 1993). It was essentially a counter agrarian reform process that played a crucial role in the spatial expansion of capitalism in the country (Ianni 1981). Impoverished small farmers were brought mainly from the southern states to try the same strategy adopted by their ancestors, who previously had to leave Germany and Italy and moved to Brazil in search of a piece of land and a secure future (Schwantes 1989). As it is widely known, social mobility was notoriously restricted in the Brazilian countryside, but the frontier raised the promise of social betterment and the possibility to own a much larger property. Early research conducted by Oliveira (1983) ascertained that families of farmers coming from the south were sincerely in search of better conditions in the context of the progress announced by the government. In practice, poor peasants and small farmers struggled to reinitiate their lives in the adverse places of the frontier. The situation was worse for the indigenous populations, who could either move to precarious and fragile reservations or be decimated by diseases and abject exploitation. Besides the activity of individual farmers, private companies were encouraged to acquire land in the frontier with the promise of generous public incentives and subsidies, although these were often siphoned off to finance activities and enrich people in other parts of Brazil (Cardoso and Müller 1977).

The overall course of events was similar, but in the opposite direction, to the genesis of capitalist farming described by Marx. If in Europe, “the expropriation of the agricultural producer, of the peasant, from the soil is the basis of the whole process” and the pillar “of the capitalist mode of production” (Marx 1976, p. 876 and 934), what happened in Brazil was the displacement of peasants from their original places followed by a poverty-induced migration to Mato Grosso that was again based on the displacement of the existing socio-spatial configurations. Those internally coupled processes of displacement (i.e. in the south and in Mato Grosso) happened as a coordinated form of primitive accumulation imposed by the political centres of Brazil, that made pervasive use of fraud and violence. For instance, the town of Sorriso, in the centre of the Teles Pires region, was a result of the occupation in 1972 by private developers of a property that belonged to the farmer Edmund Zanini, who was basically deceived and eventually displaced from the area he had purchased in 1964 (Folha de São Paulo 2009).Footnote 4 Not by chance, in a book by the local historians Dias and Bortoncello (2003), the brutality of displacement is concealed and Sorriso is praised as a beacon of abundance and economic growth that compensated for the ‘loss of the paradise’ in the south of Brazil (this is epitomised in the words of the poem ‘My Place’ on the back cover of the book). Three decades later, Sorriso, located at the edge of the forest and with huge areas of easily cultivable land, is now the main hub of soybean production for the entire country (Jepson et al. 2010).

The town of Sinop, which is now the most important administrative centre in the region, had a similar trajectory of settlement associated with displacement. The process started with the acquisition of 645,000 hectares in 1970 by a colonisation company (itself called Sinop), a property known as Gleba Celeste. The urban area of Sinop started to be opened in 1972 and soon had more than 500 timber mills processing the result of intensive deforesation. The head of the colonisation company, Ênio Pipino, famously declared that Gleba Celeste “was a green world, sleeping, in the loneliness of the Amazon” (in Souza 2006, p. 144) and also that he was “planting civilisations” and creating a liveable Amazon by opening roads and clearing forests and jungles (Pipino 1982). The vector of displacement underpinning place-making continued unabated, as an persistent phenomenon based upon dispossession and constant movement rather than upon stability, through which different layers of belonging, ties to land and group identity could be revealed (Connor 2012).

Despite the immediate material success of the new agricultural frontier (in terms of settling people and removing the original vegetation), at the same time as new farmers continued to arrive in the Teles Pires region, most ruined entrepreneurs left for other parts of the Amazon and beyond. Tragically, a significant proportion of those who came in search of their own piece of land eventually returned to their places of origin in the south or, alternatively, had to find employment in the increasingly large agribusiness farms (Barrozo 2010). This was particularly evident in the municipality of Lucas do Rio Verde, which relocated 203 families of small farmers from the State of Rio Grande do Sul (Oliveira 2005); after a difficult beginning, just a minority of the original pioneers remained in Lucas do Rio Verde—less than 10 %—while most lost their properties due to the operational adversities, unfulfilled promises and accumulated debts (Oliveira 1989; Santos 1993). The fact that the frontier was strategically open for just a relatively short period of time in the 1970s and 1980s suggests that the vector of displacement conceded some space to its opposite—replacement—in order to consolidate the meaning of the emerging socio-economic and politico-spatial relations.

The inventive force of replacement (end of 1980s–2000s)

The previous section discussed how the making of new places at the frontier was achieved through displacement, (involving the arrival of thousands of migrants in the short interval of only a few decades), the large-scale removal of the original vegetation, and the introduction of a gradually more intense production. The mechanics of displacement was hegemonic in the attempt to overcome the residues of pre-capitalist society, impose a new spatial order and facilitate the access to territorialised resources (land, water, timber, bushmeat, etc.). However, displacement could not happen in isolation and, even as the existing socio-spatial features were being displaced, another key force—replacement—was emerging. Especially from the late 1980s, some of the groups initially attracted to the agribusiness frontier were becoming redundant and had to swiftly adapt to a reality fraught with unexpected difficulties. It became increasingly evident that land in the new places had never been available to all newcomers. Less productive workers and decapitalised farmers lost their position and were largely replaced by a small number of skilled machine operators (trained to cope with the rapid automatisation and informatisation of farming procedures). The initial movement of attraction and displacement was followed by an increasingly strong process of repulsion and replacement.

In the first period of the agribusiness frontier, due to the political and economic risks involved, a large number of migrants were essential for the consolidation of the frontier, thus justifying investments in infrastructure, securing policy concessions and satisfying public opinion that something was being done about agrarian tensions in the south. Soon after this foundational moment, several political and economic constraints affected the ability of the federal administration to keep the doors wide open (in particular because of a public debt out of control and high rates of inflation in the late 1980s). In this way, the same frontier that attracted migrants, as a seductive mirage and promise of a better life, began to expel a significant proportion of those who moved to Mato Grosso. For such vulnerable players there were basically three main options: become labourers in rural properties, try to receive a small plot in agrarian reform projects or transfer their activity to a small farmstead near to the towns.Footnote 5 As observed by Marx (1976, p. 905), the capitalist farmer results from the enrichment of some individuals who usurped the common land (with the impoverishment of “the mass of the agriculture folks”) and managed to benefit from technological revolutions. Land concentration was fuelled by significantly higher land prices following the economic success of the frontier, which in Mato Grosso increased by 514.1 % between 2002 and 2013 (compared to the national average of 308.1 % in the same period), according to an assessment by the Ministry of Agriculture and the University of Brasília published in 2015.

Replacement was not only restricted to the concentration of landed property and the conversion of the weaker farmers into farm labourers. It involved other profound changes in economic and technological trends, including the substitution of the various crops unsuccessfully tried in the 1970s (coffee, cassava, guarana, pepper, rice, etc.) with the overpowering presence and symbolic importance of soybean (predicated on the use of intense agronomic techniques, expensive machinery and financialisation of production). In this particular context of place-making, the soybean was victorious from the outset, inevitably, because it played a central role in the consolidation of a model of regional development reliant on crop exports, in the hands of large farmers and trans-national corporations. The Teles Pires has in effect become a large soyscape and those who controlled soybean controlled the flows of money. Since then, what really started to matter in the region, and affect the social status of most people, was the overpowering entity ‘soybean-money’. The production of soybean almost doubled every year during the 1980s in Mato Grosso and continued to grow in double figures in the following years. The farmers also became better organised and created, in 1993, a highly effective technological institute, the MT Foundation, responsible for the development of new soybean varieties that are more productive and disease resistant. Yet the advance of soybean production was not linear. Because of state reforms and monetary stabilisation plans, the early 1990s constituted a challenging period for the Brazilian agriculture sector. Agriculture was increasingly influenced by events taking place outside the sector, including trade liberalisation, deregulation, credit reforms and removal of price support policies.

After a moment of great turbulence, there was a revitalisation of the frontier since the end of the decade, helped by currency devaluation in 1999, foreign investments in productive, and speculative, ventures; and growing demands from Asia (especially from China). Many transnational corporations (TNCs) were attracted to the Teles Pires in the period between 1999 and 2005, when booming commodity prices resulted in a sizable increase in crop production under the influence of replacement pressures. There are also other political and symbolic repercussions of the uncompromising replacement of farmers and technologies in the Teles Pires. Soybean production has been constantly portrayed by sector representatives as a fine expression of technological efficiency and administrative knowhow, which is used as undisputed evidence that rational, high-tech development works. This strong defence of soybean agribusiness was also helped by the fact that rural leaders increasingly entered the politico-electoral system (such as mayor Pivetta, vice-governor Fávero and, most famously, former governor, senator and since 2016 secretary of state for agriculture Blairo Maggi, owner of one of the most powerful Brazilian TNCs). The prevailing claim is that technified agribusiness has replaced the tradition of chaos, incompetence and turbulence typically associated with previous rounds of economic development in the Amazon with a new socio-spatial reality based on rationalism, knowledge and competence. It is an essentialist perspective by those who control place-making that, in practice, constantly denies alternative forms of agriculture or a different socio-economy. The symbolism and rhetoric of the successful frontier plays an important role in the definition of the new agriculture places against other possibilities who are outside (what Massey 1994 describes as the production of selective inclusion and also of boundaries of exclusion).

However, claims of success and technological innovation are insufficient to conceal the mounting contradictions of the agribusiness frontier. According to the federal environmental agency IBAMA, soybean accounted for most of Mato Grosso’s environmental problems because of deforestation (Repórter Brasil 2010), while the state was responsible for 70 % of national deforestation in the year 2015 (Garcia 2015). As in most of the Amazon region, agribusiness development superimposed an urban logic, and globalisation tendencies, over regional place-making. Less than 30 % of the population now live in the countryside and landowners typically live in the cities and commute every day, only spending more time in the rural property during seeding and harvesting periods. Those towns are agribusiness municipalities with high levels of urbanisation and a range of specialised services to attend to the demands of modern agriculture (including logistics and financial services), but also with marked contrasts between the wealthy centre and a growing urban periphery consisting of low-paid workers and the unemployed (Elias 2007). There are sustained cases of racial and socio-economic discrimination against those in the periphery; normally those who came from the Northeast or other parts of the Amazon and who are typically non-white migrants. The mismatch between the positive image of the frontier and the crude experience on the ground produces a tough synthesis to pull off.

The resulting sense of misplacement

From the above, it can be argued that place-making in the Teles Pires produced urban and rural landscapes of intense economic activity that are also fraught with difference, tensions and inequalities. The high-tech agriculture practiced in the Teles Pires did secure national and international prestige among agribusiness players and is now widely praised for its productivity, rationality and entrepreneurialism. At the same time, there are striking contrasts, for example, between wealthy urban areas and agribusiness farms on the one hand, and the poverty of urban peripheries and small family farms on the other. Because of its unique genesis and turbulent advance, it seems that there is more than just ostentation and socio-spatial inequality in the agribusiness frontiers of the Teles Pires. Despite signs of progress and opulence, place-making in the Teles Pires continues to be in a state of great uncertainty and complex economic, technological and social constraints. One main source of instability is the fact that, because of the politico-economic crisis of the 1990s, the region was inserted too easily into the circuits of global agri-food markets and neoliberal economic reforms (Ioris 2015). Public and private life has been affected by those adjustments which, despite renovating the regional economy, reinforced the pattern of socio-ecological exploitation, vulnerability and political subordination to the main centres of power.

What is also particularly remarkable in the case of the Teles Pires is that the unsettling dialectics of displacement and replacement continues to define place-making in the region long after the opening of the agricultural frontier. Present-day circumstances remain greatly based on the original mechanisms of territorial conquest and political control put in practice since the middle of the last century. The violent displacement of the earlier socio-ecological condition was not followed by a condition of spatial stability, but was instead complemented, and magnified, by a never-ending replacement of people, knowledge and social practices. Rather than the more common succession of displacement by emplacement (as the consolidation of the spatial configuration that probably characterises most agricultural frontier areas), what happened in the Teles Pires was the perpetuation of displacement by new waves of replacement. It is precisely this synergy between displacement and replacement that facilitated the employment of some of the oldest methods used in the Brazilian countryside, such as the exploitation of the workers and large-scale deforestation. The agricultural frontier was established to serve, and continues to attend, primarily, the politico-economic agendas of such powerful economic groups in the region and, most importantly, outside Mato Grosso. The consequence is place-making embedded in trans-spatial flows and international networks through power exercised extra-territorially.

All things considered, place-making in the Teles Pires continues to move at a fast pace, but remains based on a fundamental paradox between the presumption of progress and collective achievement, and the concealment of the fact that most social and economic opportunities are increasingly restricted. While agribusiness is ubiquitous—not as merely an economic activity, but as the holy grail of modernisation—in reality it is touched by very few. The local population now lives a strange, increasingly troubled, disconnection between the proclaimed success of the agriculture frontier and the emerging realisation that not everything corresponds to those claims. There is a rising concern with, among other issues, the long-term viability of soybean production; the risks of a very narrow economic base; the isolation of the region in relation to input suppliers and soybean buyers, and the hidden agenda of politicians and sector representatives.

These suggest that several decades of the spatial dialectics of displacement and replacement actually resulted in a pervasive, although often silent, sentiment of misplacement. Despite all the positive images transmitted daily in the local and national media, the region seems misplaced, its future is ambiguous and most of the population still struggle to reconcile being and belonging. New places have been produced, and afterwards many have been destroyed, because of the alleged advantages of the agriculture frontier, whereas these are, in effect, signs of great weakness. Moreover, misplacement is not a passive synthesis of displacement and replacement, but it is actually the third term of a highly idiosyncratic ‘trialectics’ (cf. Ioris 2012) and, therefore, has also become an active driving force in the process of place-making. For instance, the sense of misplacement in the Teles Pires is appropriated by the hegemonic groups and then used as justification for new rounds of capital accumulation under strong calls for efficiency, better logistics and competitiveness. The fact that misplacement is the dialectical synthesis of the interplay between displacement and replacement, reveals the full extent of the colonisation of space by capital and the production of abstract space, as long argued by Lefebvre.

Finally, the recognition that misplacement has also been converted into a force for place-making has another unexpected and probably surprising result: the progressive and disturbing shrinking of space in the Teles Pires. In other words, the regional space has not only been produced through place-making, but has also been wasted, corrupted and ultimately diminished. If the physical map of Mato Grosso retains the same nominal area (around 90 million hectares) and the Teles Pires has the same boundaries as 40 years ago (with an increasing number of municipal authorities), the social and socio-ecological space has gradually reduced year by year because of the perverse model of place-making adopted to open the agribusiness frontier. The process of place-making has relied on the acute degradation of nature, the destruction and waste of timber, land and biodiversity, and on the subjugation of those who came to the region naively in search of an improved future. An important element of the reduction of space when the agricultural frontier advances is the decoupling of intense farming from food production. This problem is not unique to the Teles Pires region, but it is particularly embarrassing that the main area of agribusiness production in the country is, in effect, a large food desert where most of the basic staple foods, such as rice, beans and vegetables, are imported from other Brazilian states. Likewise, the concentration of land (a typical agribusiness property has between 1000 and 2000 ha) led to an agriculture system that is less efficient per area of cultivation when compared with smaller properties, especially those below 100 ha (Helfand and Levine 2004). Overall, the prevailing direction of place-making under the influence of agribusiness has produced a reality of prevalent misplacement, in which places are less ecologically viable, more unstable and even smaller than the previous socio-spatial situation before the opening of the frontier.

The frustrated ‘invention’ of Mato Grosso

Due to the convergence of developmentalist policies and the attraction of large contingents of migrants, the northern section of Mato Grosso has become one of the last, and most important, frontiers of agricultural expansion in the world. Instead of a gradual advance of private property and market transactions, the government planned and imposed new places upon vast areas and easily mechanisable tablelands in the Teles Pires since the early 1970s. The prevailing mechanisms of place-making has been the propagation of displacement through a recurrent replacement of people and conditions of production, which results in a widespread sense of misplacement. This hegemonic direction of regional development followed a very different trajectory to that envisioned by Manoel de Barros for his homeland. In the 1920s, the poet wished for an ‘invention’ of Mato Grosso to replace a reality fraught with anachronisms and subject to spatial forces that isolated people into remote communities. Manoel wanted a new spatial order that were more inclusive and less fragmented. However, from the empirical evidence available now, there is plenty of material to infer that Manoel’s stipulation was not observed. On the contrary, the geographical typology provided by Manoel—that is, the difference between invention (as something genuine and positive) and falsehood (as inauthentic and dubious)—helps us to realise that has place-making in the Teles Pires has been an accumulation of lies, instead of the proper invention of the world. That happened through another crucial paradox (in a long sequence of perverse paradoxes, some discussed above): what was considered too simple a space was displaced and replaced with an even simpler space, which is only deceptively more sophisticated or more advanced.

What existed before had to be violently displaced through the firm hand of the state and the involvement of a large number of impoverished farmers from the south of Brazil (and also some business enterprises in search of the easy, subsidised government incentives). The region was opened up to public and private colonisation schemes and rent-seeking companies in an intense place-making process boosted by the state through the construction of roads, airfields, storage facilities and the growing expansion of urban settlements. Soon after the frontier was considered irreversible, there was potentially an opportunity to accommodate the needs and aspirations of all those initially involved. Not even that was achieved. Although at first the aim was to occupy areas considered (or made) empty and cope with major structural deficiencies in the best way possible, since the 1980s the main driving-force was to replace the promise of land for all and emphasise high-tech, efficient agribusiness production as the only way forward. Instead of making the world bigger, as Manoel wanted, place-making has been characterised by spatial compression through the accumulation of land and accelerated financialisation of production (particularly under the sphere of influence of TNCs and private banks). The ultimate result is that Mato Grosso’s space has been shrinking since the early days of the agricultural frontier, due to socio-cultural and socio-ecological erosion.

In the end, the agribusiness frontier in the Teles Pires is not only a chain of numerous places that are profoundly interconnected, but the new places also reveal a great deal about tensions related to spatial change and are themselves geographical frontiers. Beyond the apparent uniformity of crop fields and the homogeneity of plantation farms there are major social inequalities, the almost forgotten genocide suffered by indigenous groups and the risks of a socio-economy reliant on a single activity (soybean). Although the advocates of agribusiness make optimistic claims about the positive qualities of the new places, they systematically pursue strategies that are inherently partial and leave most of the population and socionature behind. That leads us to a final and very disconcerting observation: there was nothing inevitable in the process of rural and regional development promoted in the Teles Pires, but at the same time the problems, conflicts and injustices that characterise its turbulent geographical trajectory were all more or less visible from the outset. Very little could have been different, considering the past process of territorial conquest in Brazil and the brutal advance over the Amazon in the last century. In other words, the new places at the frontier have been impregnated with the worst forms of money-making, aggression and racism. The consequence is that, more than the soybean, the deceptiveness of place-making is the main contribution of this agricultural frontier to the rest of the world.

Notes

Teles Pires is a forming tributary of the Tapajós River, a main affluent of the mighty Amazon.

Information about the documentary can be seen at: www.sodez.com.br. The poet was extremely reserved and his work was only revealed to the wider public in recent decades when some well-known intellectuals started to praise the relevance of Manoel’s poetry.

Obviously democracy and development only applied to white settlers.

The Zanini family fled Mato Grosso in 1977 and the dispute was only resolved by the courts in 2011.

To avoid the replacement of those who had just been replaced, municipal authorities introduced an informal ‘place filter’ that prevented the entrance of poor, unwanted migrants: for a while, at the bus station of Sorriso and Sinop there was a formal check and those unable to demonstrate secured income receive a free ticket back home.

References

Agnew, J. A. (2011). Space and place. In J. A. Agnew & D. Livingstone (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of geographical knowledge. London: SAGE Publications.

Antonsich, M. (2010). Meanings of place and aspects of the self: An interdisciplinary and empirical account. GeoJournal, 75(1), 119–132.

Arenas, H. S., & Geisse, M. G. (2004). La aproximación humanística en Geografía. Revista de Geografía Norte Grande, 31, 31–52.

Ash, J., & Simpson, P. (2016). Geography and post-phenomenology. Progress in Human Geography, 40(1), 48–66.

Barney, K. (2009). Laos and the making of a ‘relational’ resource frontier. The Geographical Journal, 175(2), 146–159.

Barros, M. (2013). Poesia completa. São Paulo: LeYa.

Barrozo, J. C. (Ed.). (2010). Mato Grosso: A (re)ocupação da terra na fronteira Amazônica (Século XX). Cuiabá: EdUFMT.

Bartos, A. E. (2013). Children sensing place. Emotion, Space and Society, 9(1), 89–98.

Brasil, Repórter. (2010). Impacts of soybean on the 2009/10 harvest. São Paulo: NGO Repórter Brasil.

Bridge, G. (1997). Mapping the terrain of time—space compression: Power networks in everyday life. Environment and Planning D, 15(5), 611–626.

Cardoso, F. H., & Müller, G. (1977). Amazônia: Expansão do capitalismo. São Paulo: Brasiliense/CEBRAP.

Chouinard, V. (1990). State formation and the politics of place: The case of community legal aid clinics. Political Geography Quarterly, 9(1), 23–38.

Connor, T. K. (2012). The frontier revisited: Displacement, land and identity among farm labourers in the Sundays River Valley. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 30(2), 289–311.

Cosgrove, D., & Jackson, P. (1987). New directions in cultural geography. Area, 19(2), 95–101.

Darling, J. (2009). Thinking beyond place: The responsibilities of a relational spatial politics. Geography Compass, 3(5), 1938–1954.

Das, R. J. (2012). Reconceptualizing capitalism: Forms of subsumption of labor, class struggle, and uneven development. Review of Radical Political Economics, 44(2), 178–200.

Deininger, K. W., & Byerlee, D. (2011). Rising global interest in farmland. Washington DC: World Bank.

Dias, E. A., & Bortoncello, O. (2003). Resgate histórico do Município de Sorriso. Cuiabá: Print Express.

Dirlik, A. (1999). Place-based imagination. Review, 22(2), 151–187.

Dyck, I. (2005). Feminist geography, the ‘everyday’, and local-global relations: Hidden spaces of place-making. Canadian Geographer, 49(3), 233–243.

Elias, D. (2007). Agricultura e produção de espaços urbanos não metropolitanos: Notas teórico-metodológicas. In M. E. B. Sposito (Ed.), Cidades média: Espaços em transição. São Paulo: Expressão Popular.

Folha de São Paulo. (2009). Justiça de MT decidirá destino de área que vale mais de R$ 1 bi. http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/fsp/dinheiro/fi1209200918.htm. Accessed 18 May 2015.

Garcia, R. (2015). A volta do desmatamento na Amazônia. Scientific American Brasil, 157, 26–31.

Harvey, D. (2006) [1982]. The limits to capital. London and New York: Verso.

Helfand, S. M., & Levine, E. S. (2004). Farm size and the determinants of productive efficiency in the Brazilian Center-West. Agricultural Economics, 31(2–3), 241–249.

Ianni, O. (1981). A luta pela terra: História social da terra e da luta pela terra numa área da Amazônia. Petrópolis: Vozes.

Ioris, A. A. R. (2012). Applying the strategic-relational approach to urban political ecology: The water management problems of the Baixada Fluminense, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Antipode, 44(1), 122–150.

Ioris, A. A. R. (2013). The adaptive nature of the neoliberal state and the state-led neoliberalisation of nature: Unpacking the political economy of water in Lima, Peru. New Political Economy, 18(6), 912–938.

Ioris, A. A. R. (2015). Cracking the nut of agribusiness and global food insecurity: In search of a critical agenda of research. Geoforum, 63, 1–4.

Jepson, W., Brannstrom, C., & Filippi, A. (2010). Access regimes and regional land change in the Brazilian cerrado, 1972–2002. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 100(1), 87–111.

Lems, A. (2016). Placing displacement: Place-making in a world of movement. Ethnos, 81(1), 315–337.

Marx, K. (1976 [1867]). Capital: A critique of political economy (vol. 1). Penguin: London.

Massey, D. (1993). Power geometry and a progressive sense of place. In J. Bird, B. Curtis, T. Putnam, G. Robertson, & L. Tickner (Eds.), Mapping the futures. London: Routledge.

Massey, D. (1994). Space, place, gender. Cambridge: Polity Press.

May, J. (1996). Globalization and politics of place. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 21(1), 194–215.

Mcdowell, L. (2015). Roepke Lecture in economic geography—The lives of others: Body work, the production of difference, and labor geographies. Economic Geography, 91(1), 1–23.

Moreno, G. (2007). Terra e poder em Mato Grosso: Política e mecanismos de burla 1892–1992. Cuiabá: EdUFMT/Entrelinhas.

Oliveira, J. M. (1983). A esperança vai na frente: contribuição ao estudo da pequena produção em Mato Grosso, o caso de Sinop. M.Sc. dissertation, São Paulo: FFLCH/USP.

Oliveira, A. U. (1989). Amazônia: Monopólio, expropriação e conflitos. Campinas: Papirus.

Oliveira, A. U. (2005). BR-163 Cuiabá-Santarém: geopolítica, grilagem, violência e mundialização. In M. Torres (Ed.), Amazônia revelada: Os descaminhos ao longo da BR-163. CNPq: Brasilia.

Pierce, J., Martin, D. G., & Murphy, J. T. (2011). Relational place-making: The networked politics of place. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 36(1), 54–70.

Pipino, E. (1982). Não há ‘inferno verde’ (interview by O. Ribeiro). Contato, 33, 3–6.

Pocock, D. C. D. (Ed.). (1981). Humanistic geography and literature: Essays on the experience of place. London: Croom Helm.

Qian, J., Qian, L., & Zhu, H. (2012). Subjectivity, modernity, and the politics of difference in a periurban village in China: Towards a progressive sense of place? Environment and Planning D, 30(6), 1064–1082.

Santos, J. V. T. (1993). Matuchos: Exclusão e luta. Petrópolis: Vozes.

Schutz, A. (1972). The phenomenology of the social world. Evanston IL: Northwestern University Press.

Schwantes, N. (1989). Uma cruz em Terranova. São Paulo: Scritta.

Souza, E. A. (2006). Sinop: História, imagens e relatos. Cuiabá: EdUFMT/FAPEMAT.

Swyngedouw, E. A. (1999). Marxism and historical-geographical materialism: A spectre is haunting geography. Scottish Geographical Journal, 115(2), 91–102.

Thornton, P. M. (2010). From liberating production to unleashing consumption: Mapping landscapes of power in Beijing. Political Geography, 29(6), 302–310.

Thrift, N. (1983). Literature, the production of culture and the politics of place. Antipode, 15(1), 12–24.

Tuan, Y.-F. (1976). Humanistic geography. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 66(2), 266–276.

Villas Bôas, O., & Villas Bôas, C. (1994). A marcha para o oeste: A epopéia da expedição Roncador–Xingu. São Paulo: Globo.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by CAPES (Grant No. PVE 055/2012)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical standards

The research and the manuscript comply with all ethical standards, especially those put forward by CAPES and by the University of Edinburgh.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ioris, A.A.R. Place-making at the frontier of Brazilian agribusiness. GeoJournal 83, 61–72 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-016-9754-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-016-9754-7