Abstract

Using the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 as a natural experiment, we document a non-monotonic relation between board independence and credit ratings. Ratings are upgraded with an exogenous increase of board independence only when independence is low, which is consistent with the costs as well as benefits of having independent directors. Further analysis suggests that these costs may include the deficiency of the industrial expertise of independent directors, the cost of information acquisition for independent directors to become informed to monitor management, and the risk-taking incentive of these directors that may adversely affect the credit risk of a financially distressed firm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In contrast, inside or executive directors are directors who are employees of the firm, and grey or linked directors are directors who, though not the employees of the firm, have some business transactions with the firm. One example of a grey director is an executive of the supplier of the firm sitting as one of its directors.

Chen (2008) documents that higher firm performance brings more independent directors who are active executive directors of other firms. Crutchley et al. (2002) and Fahlenbrach et al. (2010) show that independent directors often leave financially troubled firms. Since higher credit ratings are often associated with better firm performance, these studies suggest that the addition (departure) of independent directors may be a result of higher (lower) ratings.

Though rating agencies generally favor higher board independence, they also recognize the potential costs of “nominal” independence. For example, Moody’s (2004, p.6) states “there can also be tension between a board’s need for independence and its need for industry, or even company-specific, knowledge and experience.” Fitch Ratings (2004, p.10) also regards the flow of information between management and the board as important for the effectiveness of a board. Because higher independence may compromise such information flow (Adams and Ferreira 2007), independent directors may be costly. Finally, Moody’s (2003, p.6) states that “some director compensation arrangements that are substantial and rely heavily on stock options or other relatively ‘risky’ pay elements also may merit comment as potentially encouraging risk-taking that could be excessive from a creditor standpoint.” Therefore, independent directors compensated with options and/or stocks may also be costly to creditors.

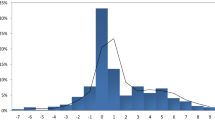

In undocumented analysis, we also employ stand-alone FE models to examine a non-monotonic relationship between independence and ratings. We entertain specifications with either the squared term of board independence or piecewise linear functions of independence similar to Morck et al. (1988). Our results are similar. Compared with the DID models which mainly rely on the change of independence around the event date, the FE specification relies on the time-series variation of independence during the entire sample period. We also document a dramatic change of results on a monotonic relationship between independence and ratings with or without the control of fixed firm effects, which suggests that the results obtained in the extant literature are sensitive to model specifications.

Ruling out the possibility that the relation between board independence and credit ratings may merely reflect the models that rating agencies employ, which may have little to do with the actual credit risk of a firm, in untabulated analysis we demonstrate a similarly non-monotonic effect of board independence on bond spreads, which are another proxy of credit risk. Our data for bond spreads come from a proprietary database of S&P.

See, for example, the Shareholder Bill of Rights Act introduced in the U.S. Senate in May, 2009, in which it states that “among the central causes of the financial and economic crises that the United States faces today has been a widespread failure of corporate governance.” The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 also prescribes that all compensation committee members be independent directors, and that shareholders may use a company’s proxy solicitation materials to nominate their own directors.

There is a growing strand of literature on the effectiveness of credit ratings and rating agencies (e.g., Alp 2012; Baghai et al. 2012; Becker and Milbourn 2011; Bolton et al. 2012; Jiang et al. 2012). As a result of their alleged role in facilitating the recent financial crisis, the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 tightened the monitoring of rating agencies.

Most criticisms to the rating agencies for their potential role in the recent financial crisis are focused on ratings of structured products such as mortgage-backed securities, rather than industrial firms.

The NYSE further requires all its listed firms to have fully independent compensation and nomination committees. Though it is not required that firms listed in the NASDAQ and the American Exchange (AMEX) have the two committees, these two committees have to be fully independent if firms choose to have them.

For example, the NYSE requires independent directors to be non-employees, to have no prior employment with the firm or to have terminated the employment at least 3 years before they serve as directors, and to have no substantial business transactions with the firm. RiskMetrics goes further by requiring independent directors to have no prior employment and business transactions with the firm at all.

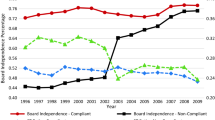

The compliance statistics in Panel A of Table 2 show that by year 2005 still 3 % of the firms were not compliant, which is puzzling. This puzzle is also observed in Chhaochharia and Grinstein (2009) and Kim and Lu (2012). Similar to these studies, we also find based on manual search of proxy statements, that the vast majority of these non-compliant firms actually declared that they were compliant. Therefore, it appears that most of these non-compliant cases are due to the stricter definitions of independence according to RiskMetrics.

In undocumented analysis, we also confirm the statistical similarity between the rating changes of the non-compliant and compliant firms between 2002 and 2003.

In unreported analysis, we also confirm an overall significantly positive effect of independence on ratings based on the full sample but from 1996 to 2003, rather than from 1996 to 2005 as in Model 1.

It is notable that our DID results crucially depend on whether we control for fixed firm effects or not. Without the fixed-effects, all the significant results disappear. This is consistent with our observation in Panel C of Table 2 that the non-compliant and compliant firms are similar on the observational characteristics. Therefore, controlling for the non-observable fixed-effects is important in our study.

If rating agencies are forward-looking in assigning ratings (Hovakimian et al. 2009), then the rating upgrades for the very non-compliant firms should also be more significant than those of the barely non-compliant firms, because the independence of the very non-compliant firms is lower to start with. However, this “forward-looking hypothesis” cannot account for the fact that despite a more significant increase of board independence for the barely non-compliant firms relative to the compliant firms, their rating changes are not significantly different from each other. In unreported analysis, we find that a further significant increase of independence of the very non-compliant firms after 2003 continues to improve their ratings, which is also inconsistent with the forward-looking hypothesis. This is because if rating agencies are forward-looking, they should already have factored the ultimate effect of independence on ratings in 2003, and hence should not further upgrade the ratings afterwards.

We also consider the balance of these different aspects of expertise within a board. In addition, we use the number of outside directorships to represent the expertise of a director, since a more talented director may sit on more boards. But rating changes of the non-compliant firms are not statistically different from each other based on these proxies of director expertise.

Results using Fama-French 48-industry classifications are similar. Results that focus on independent directors who are active executive directors of other firms in the same industries are also similar.

Results using the numbers of different types of independent experts, rather than their fractions are similar.

Results are similar based on the earnings forecasts for the next fiscal year. We thank John Matsusaka for suggesting these measures of information asymmetry.

Following Duchin et al. (2010), we use the residuals of the regressions of the number of analysts on the book value of total assets as the measure of the availability of analyst coverage. This takes into account the fact that larger firms often have more analysts following, and firm size is also directly related to credit ratings.

Following Chhaochharia and Grinstein (2009), we use the Herfindahl index of institutional shareholdings to measure the concentration of institutional shareholdings. Results are similar using the percent of institutional blockholdings with at least 5 % ownership or a dummy for the presence of an institutional blockholder with at least 5 % ownership. We use the G-index to measure the strength of takeover defense (Gompers et al. 2003). We use the CEO cumulative shareholdings to measure executive shareholdings. Results using CEO incentive compensation, including stocks and options are similar.

We also use the Altman’s Z-score and interest coverage ratio to indicate a firm’s distance to financial distress, and find insignificant difference between the rating changes for firms with different Z-scores or interest coverage ratios. In addition, we follow Johnson (1998) and use the ratio of fixed assets to total assets to proxy for the tendency of risk-shifting (asset substitution) by shareholders. But the results are also insignificant.

Unlike executive compensation, EXECUCOMP does not provide the Black-Scholes value of options for directors. We follow Farrell et al. (2008) and approximate this value by the per grant Black-Scholes value of CEO’s option awards multiplied by the number of annual director options. If the CEO is not granted any options in a given year, we calculate the average per grant Black-Scholes value of the other top four executives, and multiply this value by the number of annual director options. We calculate the value of director stock grants by multiplying the number of annual stock grants by the share price at the end of the previous fiscal year.

For completeness, we also include the interaction terms Low Director incen comp * Dummy (per_ind < 0.5 ‘02) * Post-SOX and Low Director ownership * Dummy (per_ind < 0.5 ‘02) * Post-SOX respectively in the two models. We thank an anonymous referee for pointing this out.

Our results are qualitatively similar if matching based on one-digit SIC or Fama-French 48 industries.

References

Adams R (2012) Governance and the financial crisis. Int Rev Financ 12(1):7–38

Adams R, Ferreira D (2007) A theory of friendly boards. J Financ 62(1):217–250

Adams R, Ferreira D (2009) Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance. J Financ Econ 94:291–309

Adams R, Hermalin B, Weisbach M (2010) The role of boards of directors in corporate governance: a conceptual framework and survey. J Econ Lit 48(1):58–107

Alp A (2012) Structural shifts in credit rating standards. J Financ Forthcoming

Anderson RC, Mansi SA, Reeb DM (2004) Board characteristics, accounting report integrity, and the cost of debt. J Account Econ 37(3):315–342. doi:10.1016/j.jacceco.2004.01.004

Andrade S, Bernile G, Frederick H (2009) SOX, corporate transparency, and the cost of debt. Working Paper, University of Miami

Ashbaugh-Skaife H, Collins DW, LaFond R (2006) The effects of corporate governance on firms’ credit ratings. J Account Econ 42(1–2):203–243. doi:10.1016/j.jacceco.2006.02.003

Baghai R, Servaes H, Tamayo A (2012) Have rating agencies become more conservative? Implications for capital structure and debt pricing. Working Paper, London Business School

Becker B, Milbourn T (2011) How did increased competition affect credit ratings? J Financ Econ 101(3):493–514

Beltratti A, Stulz RM (2009) Why did some banks perform better during the credit crisis? a cross-country study of the impact of governance and regulation. Working Paper, Ohio State University

Bhojraj S, Sengupta P (2003) Effect of corporate governance on bond ratings and yields: the role of institutional investors and outside directors. J Bus 76(3):455–475

Blume ME, Lim F, Mackinlay AC (1998) The declining credit quality of US corporate debt: myth or reality? J Financ 53(4):1389–1413

Bolton P, Freixas X, Shapiro J (2012) The credit ratings game. J Financ 67(1):85–111

Bongaerts D, Cremers KJM, Goetzmann WN (2012) Tiebreaker: certification and multiple credit ratings. J Financ 67(1):113–152

Boone AL, Field LC, Karpoff JM, Raheja CG (2007) The determinants of corporate board size and composition: an empirical analysis. J Financ Econ 85(1):66–101

Bradley M, Chen D (2011) Corporate governance and the cost of debt: evidence from director limited liability and indemnification provisions. J Corp Financ 17(1):83–107

Cantor R, Packer F (1994) The credit rating industry. Federal Reserve Bank of New York - Quarterly Review Summer-Fall:1–26

Chen D (2008) The monitoring and advisory functions of corporate boards: theory and evidence Working Paper, University of Baltimore

Chhaochharia V, Grinstein Y (2007) Corporate governance and firm value: the impact of the 2002 governance rules. J Financ 62(4):1789–1825

Chhaochharia V, Grinstein Y (2009) CEO compensation and board structure. J Financ 64(1):231–261

Crutchley CE, Garner JL, Marshall BB (2002) An examination of board stability and the long-term performance of initial public offerings. Financ Manage 31(3):63–90

de Andres P, Vallelado E (2008) Corporate governance in banking: the role of the board of directors. J Bank Financ 32(12):2570–2580

DeFond M, Hung M, Karaoglu E, Zhang J (2011) Was the Sarbanes-Oxley Act good news for corporate bondholders? Account Horiz 25(3):465–485

Duchin R, Matsusaka JG, Ozbas O (2010) When are outside directors effective? J Financ Econ 96:195–214

Ecker F, Francis J, Kim I, Olsson PM, Schipper K (2006) A returns-based representation of earnings quality. Account Rev 81(4):749–780

Ertugrul M, Hegde S (2008) Board compensation practices and agency costs of debt. J Corp Financ 14(5):512–531

Fahlenbrach R, Low A, Stulz RM (2010) The dark side of outside directors: do they quit when they are most needed? Working Paper, Ohio State University

Farrell KA, Friesen GC, Hersch PL (2008) How do firms adjust director compensation? J Corp Financ 14(2):153–162

Fich E (2005) Are some outside directors better than others? evidence from director appointments by fortune 1000 firms. J Bus 78:1943–1971

Fitch Ratings (2004) Credit policy special report, evaluating corporate governance: the bondholders’ perspective. New York

Gillan SL, Starks LT (2007) The evolution of shareholder activism in the United States. J Appl Corp Financ 19(1):55–73

Gompers P, Ishii J, Metrick A (2003) Corporate governance and equity prices. Q J Econ 118(1):107–155

Graham JR, Harvey CR (2001) The theory and practice of corporate finance: evidence from the field. J Financ Econ 60(2–3):187–243

Hermalin B, Weisbach M (2003) Boards of directors as an endogenously determined institution, a survey of the economic literature. FRBNY Economic Policy Review April:7–26

Hovakimian A, Kayhan A, Titman S (2009) Credit rating targets. Working paper. University of Texas, Austin

Jensen MC, Meckling WH (1976) Theory of firm-managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J Financ Econ 3(4):305–360

Jewell J, Livingston M (1998) Split ratings, bond yields, and underwriter spreads. J Fin Res 21(2):185–204

Jiang JX, Stanford M, Xie Y (2012) Does it matter who pays for bond ratings? Historical evidence. J Financ Econ 105(3):607–621

Jiraporn P, Chintrakarn P, Kim J-C, Liu Y (2012) Exploring the agency cost of debt: evidence from the ISS governance standards. J Financ Serv Res Forthcoming

John K, Senbet LW (1998) Corporate governance and board effectiveness. J Bank Financ 22(4):371–403

Johnson SA (1998) The effect of bank debt on optimal capital structure. Financ Manage 27(1):47–56

Kim EH, Lu Y (2012) The independent board requirement and CEO connectedness. Working Paper, University of Michigan

Kisgen DJ (2006) Credit ratings and capital structure. J Financ 61(3):1035–1072

Kisgen DJ (2009) Do firms target credit ratings or leverage levels? J Financ Quant Anal 44(6):1323–1344

Klein A (1998) Firm performance and board committee structure. J Law Econ 41:275–303

Klock MS, Mansi SA, Maxwell WF (2005) Does corporate governance matter to bondholders? J Financ Quant Anal 40(4):693–719

Linck JS, Netter JM, Yang T (2008) The determinants of board structure. J Financ Econ 87(2):308–328

Linck JS, Netter JM, Yang T (2009) The effects and unintended consequences of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act on the supply and demand for directors. Rev Financ Stud 22(8):3287–3328

McConnell JJ, Servaes H (1990) Additional evidence on equity ownership and corporate value. J Financ Econ 27(2):595–612

McConnell JJ, Servaes H, Lins KV (2008) Changes in insider ownership and changes in the market value of the firm. J Corp Financ 14:92–106

Minton BA, Taillard JPA, Williamson R (2011) Do independence and financial expertise of the board matter for risk taking and performance? Working Paper, Ohio State University

Moody’s (2003) U.S. and Canadian corporate governance assessment. Moody’s Investors Service, Global Credit Research

Moody’s (2004) Moody’s findings on corporate governance in the United States and Canada: August 2003 - September 2004. Moody’s Investors Service, Global Credit Research

Morck R, Shleifer A, Vishny RW (1988) Management ownership and market valuation - an empirical-analysis. J Financ Econ 20(1–2):293–315

Myers SC (1977) Determinants of corporate borrowing. J Financ Econ 5(2):147–175

Neyman J, Scott EL (1948) Consistent estimates based on partially consistent observations. Econometrica 16(1):1–32

Petersen MA (2009) Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: comparing approaches. Rev Financ Stud 22(1):435–480

Raheja CG (2005) Determinants of board size and composition: a theory of corporate boards. J Financ Quant Anal 40(2):283–306

Schmidt B (2009) Costs and benefits of “friendly” boards during mergers and acquisitions. Working Paper, Emory University

Standard & Poor’s (2002) Standard & Poor’s corporate governance scores: criteria, methodology and definitions. McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc, New York

Standard & Poor’s (2008) Corporate rating criteria. McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc, New York

Sufi A (2009) The real effects of debt certification: evidence from the introduction of bank loan ratings. Rev Financ Stud 22(4):1659–1691

Wintoki MB (2007) Corporate boards and regulation: the effect of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and the exchange listing requirements on firm value. J Corp Financ 13(2–3):229–250

Zhang IX (2007) Economic consequences of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. J Account Econ 44(1–2):74–115

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper was previously titled “Board Independence and Credit Ratings”. I thank an anonymous referee for very helpful comments. I thank Frederick Hood, John Matsusaka, Haluk Ünal (the editor), and the participants of FMA 2009 and SWFA 2010 conferences for valuable comments and suggestions. I thank Frederick Hood for providing the corporate opacity data. I owe a debt of gratitude to Michael Bradley for his many insightful comments for the original draft that improved the paper significantly. As always, all the errors are my own.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, D. The Non-monotonic Effect of Board Independence on Credit Ratings. J Financ Serv Res 45, 145–171 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-012-0158-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-012-0158-7