Abstract

This paper examines the trends and composition of volatility across European banking systems from January 1988 to December 2010. While there is no evidence of a long-term trend in the average level of banking system volatility, there is a change in its composition resulting from the growing importance of International and European nonfinancial components, especially in the largest banking systems. We argue that the changing composition of banking system volatility is the effect of a long-term integration process (with a growing importance of cross-border activities) that has not been influenced by the introduction of the Euro. Our results highlight the increasing vulnerability of the European banking systems to International and European shocks and an increasing likelihood of cross-border banking crises, and the need for regulatory reforms that focus on effective cross-border crisis management and resolution so as to safeguard the systemic stability of European banking in the near future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Examples in this direction are the bailouts of HBOS in the UK and Fortis in Belgium, as well as the difficulties of other UK and Irish banking groups that have led to a broad nationalization process of the banking systems in the UK and Ireland.

Moshirian and Wu (2009) show that banking industry volatility predicts banking crises in developed countries. Stiroh (2006) also provides several arguments in favor of the choice of this measure as an indicator of bank risk. For instance, volatility is relevant to regulators, managers and borrowers since they are concerned with the probability of the failure of banks and the related costs. This can be seen by the direct link between equity return volatility and asset volatility, usually employed to construct market measures of bank default risk, such as the distance to default.

Publicly traded banks are broadly representative of a country’s banking sector (Moshirian and Wu 2009). In Europe listed banks represent at least 50% of the banking system’s total assets in the majority of the EU members (ECB 2005) with the notable exceptions being Austria, Finland, Germany and Portugal. However, in these countries listed banks still represent an average of 40% of the total banking system assets.

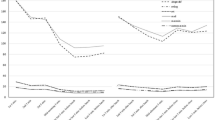

We define as ‘International nonfinancial’ the component of banking system risk related to comovements with the foreign stock markets consisting of nonfinancial firms; namely, all nonfinancial firms operating outside Europe. The ‘European nonfinancial’ component then captures the specific contribution of European nonfinancial stocks to banking volatility. Finally, the ‘International banking industry’ and ‘European banking industry’ components capture the additional contribution to banking volatility coming from, respectively, variations in the International and European banking industries, while the Country component denotes the contribution from country stock market indices. For details on the research methodology and on the definition of each component, see Section 2 and the Appendix.

In the following analysis, and in line with previous studies on the volatility of stock returns, we employ market capitalization as the size variable as it is available at high frequency intervals. An alternative choice could be to employ the value of bank total assets. However, this would pose two major difficulties. First, this variable is not available for all countries from the same data source for the full sample period. Second, when available, its values usually refer to an annual frequency.

In line with this literature, in our analysis the term ‘volatility’ denotes the variance of stock returns and not their standard deviation.

In section 7 we show that our results are qualitatively unchanged if we relax this assumption.

Therefore, our indicators are not measuring total banking volatility in Europe. Specifically, according to a portfolio approach, total volatility requires computing not only variance components but also the covariance terms between each couple of banking systems. We elaborate on this in section 4.3 where we discuss the implications of our results for the interdependencies of banking systems across Europe.

Datastream banking indices include all types of publicly traded banks in a country with the exclusion of investment banks. These indices are a subset of the more general financial service indices that also include consumer finance, other specialized financial institutions and insurance companies.

We employ this set of indices instead of indices provided by the local Stock exchanges in order to eliminate the distortions that can be generated by differences in terms of construction of the index. Furthermore we do not employ alternative sources of provider (for example, Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI)—Barra) since they are not available at a daily frequency for the whole period under consideration. The sector classifications adopted by Datastream are based on the Financial Times Stock Exchange categories (FTSE Actuaries).

At the end of 2009, according to the European Banking Federation (2009), the same group of countries holds 77% of the total assets of the 17 European banking systems included in this study; namely, a value similar to that obtained in terms of average market capitalization over the sample period.

These same figures show that the relative importance of the International and European nonfinancial components drop substantially in the years 1999–2000. Since this result has been generally found also for nonfinancial firms, it is not probably due to the impact of some specific bank effects, but can be ascribed to the temporarily deviating behaviour that stocks of some specific industrial sectors (i.e. telecoms and technology) exhibit in those years (Brooks and Del Negro 2004).

For instance, according to the ECB (2010), the total assets of branches and subsidiaries coming from one of the EU15 countries and located in the others EU15 countries are equal to 18.6% of the EU15 banking system total assets.

Banks operating in small banking systems generally show a smaller size than banks in large banking systems and this, as suggested by Baele et al. (2007) might be associated to a lower degree of functional diversification with the effect of increasing their exposure to idiosyncratic shocks. Furthermore, according to a portfolio view, a larger number of banks in the index is likely to indicate a more diversified portfolio of banks with a consequent decline in idiosyncratic risk.

This approach is characterized by several advantages as compared to the traditional OLS regression. Specifically, estimates of serial correlation parameters are not needed and the adjusted t-statistic is robust to I(0) and I(1) errors; namely, in the case of both stationary errors (I(0)) and when the errors are stationary after one differentiation (I(1)).

This statistic is used to smooth discontinuities in the limiting distribution of the statistics as the errors go from I(0) to I(1) in the case b is greater than zero. For a given significance level of the test, b can be chosen to ensure that the critical values of t−PS 1 are the same when the residuals are I(0) and I(1). As a consequence, \( J_T^1 \) ensures that the t-tests from the z t regression are robust for I(1) errors; namely, in the case of errors that are stationary after one differentiation. The critical values of these tests and the optimal values of b are provided by Vogelsang (1998).

When we limit the analysis to the pre-crisis, we do not find any significant shift in the European banking industry component.

We obtain similar results when we test for a shift in trend in total volatility and its covariance components as described in Table 5. The results of these tests are available from the authors upon request.

More precisely, the information on cross-border banking is drawn from table 8A of BIS Locational Statistics.

A different proxy of the degree of internationalization of a banking system may be represented by the share of total assets produced by foreign branches and subsidiaries in a given banking system. However, this indicator is only available over the period from 1997 to 2009 and only for the sub-set of EU15 countries. Although for a smaller sample and for a shorter time horizon, we still observe evidence of an increasing importance of cross-border banking in Europe: this ratio has increased from 20.7% to 25.0%.

The GDP-weighted average of the ratio between the international position of European banks and country GDP has achieved its maximum value (203%) in March 2008, then it has declined steadily in the latest part of the sample period.

Since the cross-border data are available at a quarterly frequency, we conduct the analysis by considering the average value of our monthly risk components in a given quarter.

For instance, this is the case of Deustche Bank and Commerzabank in Germany, Unicredit and Intesa in Italy, Banco Santander and BBVA in Spain, Royal Bank of Scotland, Lloyd and Barclays in the UK.

Ideally, we would have liked to provide a direct test of the importance of diversification of the composition of banking system volatility. However, we are not aware of any proxy of the degree of diversification at the level of the banking system that might be available at a monthly (quarterly) frequency which is the frequency of our volatility components.

We classify the banking systems as ‘relatively large’ if the ratio between market capitalization and GDP is on average above 10% over the sample period and as ‘relatively small’ the remaining banking systems. The first group consists of 8 banking systems including UK, Switzerland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Belgium, Sweden, Spain and Greece.

As an alternative criterion, we classify banking systems on the basis of the ratio between banking system total assets and country GDP at the end of 2009. More precisely, we classify as relatively large banking systems with a ratio of total assets over GDP larger than 350% and as small the remaining banking systems. While this approach produces some differences in the way we group the banking systems, with the UK, Switzerland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Belgium, Austria, France, Denmark, and the Netherlands identified as relatively large, we still observe in both groups an increasing trend in the International and European nonfinancial components. However, while the results for relatively large banking systems are similar to when the analysis has been conducted by grouping banking systems on the basis of absolute size (market capitalization), in the group of relatively small banking systems we observe a lack of any significant long-term trend in the Country and Idiosyncratic components. Nonetheless, also in these banking systems, the Country and Idiosyncratic components decline substantially over the sample period.

We compute a value-weighted average for each daily beta estimated at the country level and then we use the simple average in a given month in our trend analysis.

As this approach leads to uncorrelated factors in the return generating model, it resembles the empirical strategy applied by Drummen and Zimmerman (1992) to investigate the structure of European stock returns and by Clayton and Mackinnon (2003) to investigate the link between REIT returns and stock, bond and real estate factors. Specifically, they obtain uncorrelated components in a multifactor model by orthogonalization. However, the major difference in our approach is the assumption regarding the ‘true’ returns-generating process. As suggested by Akella and Chen (1990), under the assumption that Eq. (9A) is the ‘true’ generating process, our estimates are unbiased. Furthermore, the returns-generating process assumed in the arbitrage pricing theory (APT) is similar to Eq. (9A) (see Wei 1988).

References

Acharya VV (2009) A theory of systemic risk and design of prudential regulation. J Financ Stab 5:224–255

Akella SR, Chen SJ (1990) Interest rate sensitivity of bank stock returns: specification effects and structural changes. J Financ Res XIII:147–154

Allen F, Song W (2005) Financial integration and EMU. Eur Financ Manage J 11:7–24

Baele L, De Jonghe O, Vander Vennet R (2007) Does the stock market value bank diversification? J Bank Finance 31:1999–2023

Bartram SM, Taylor SJ, Wang YH (2006) The Euro and European financial market dependence. J Bank Finance 31:1461–1481

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2011) Global systemically important banks: assessment methodology and the additional loss absorbency requirement. Consultative document, July 2011

Beckers S, Grinold R, Rudd A, Stefek D (1992) The relative importance of common factors across the European equity markets. J Bank Finance 16:75–95

Bekaert G, Hodrick RJ, Zhang X (2008) International stock return comovements. ECB Working Paper, 931

Boot AWA, Thakor AV (2009) The accelerating integration of banks and markets and its implications for regulations. In: Berger A, Molyneux P, Wilson JOS (eds) The Oxford handbook of banking. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Brooks R, Del Negro M (2004) The rise in comovement across national stock markets: market integration or IT bubble? J Empir Finance 11:659–680

Buch C, Neugebauer K (2009) Diversification of banks’ international portfolios: evidence and policy lessons. FINESS Working paper, d.2.4

Campbell JY, Lettau M, Malkiel BG, Xu Y (2001) Have individual stocks become more volatile? An empirical exploration of idiosyncratic risk. J Finance 56:1–43

Carbo-Valverde S, Kane EJ, Rodriguez-Fernandez F (2008) Evidence of differences in the effectiveness of safety-net management in European Union countries. J Financ Serv Res 34:151–176

Cetorelli N, Goldberg LS (2008) Banking globalization, monetary transmission, and the lending channel. NBER Working Paper Series, 14101, June 2008

Cetorelli N, Goldberg LS (2010) Global banks and international shocks transmission: evidence from the crisis. NBER Working Paper Series, 15974, May 2010

Clayton J, Mackinnon G (2003) The relative importance of stock, bond, and real estate factors in Explaining REIT returns. J R Estate Finance Econ 27:39–60

De Bandt O, Hartmann P (2000) Systemic risk: a survey. ECB, Working Paper Series, 35

De Jonghe O (2010) Back to the basics in banking? A micro-analysis of banking system stability, J Financ Intermed 19: 387–417

De Nicolò G, Kwast ML (2002) Systemic risk and financial consolidation: are they related? J Bank Finance 26:861–880

De Nicolò G, Tieman A (2006) Economic integration and financial stability: a European perspective. IMF Working paper, 296

Demsetz RS, Strahan PE (1997) Diversification, size and risk at bank holding companies. J Money, Credit, Bank 29:300–313

Drummen M, Zimmerman H (1992) The structure of European stock returns. Financ Analysts J 48:15–26

Eiling E, Gerard B (2007) Dispersion. Unpublished Working Paper, Equity Returns Correlations and Market Integration

Eisenbeis RA, Kaufman GG (2008) Cross-border banking and financial stability in EU. J Financ Stab 3:168–204

European Banking Federation (2009) European Banking Statistics, available at http://www.ebf-fbe.eu/index.php?page=statistics

European Central Bank (2005) Bank market discipline. Monthly Bulletin, February 2005

European Central Bank (2010) EU banking structures, September 2010

European Commission (2009) An EU framework for cross-border crisis management in the banking sector. Commission Staff Working Document October 2009

European Commission (2010) An EU framework for crisis management in the financial sector. Communication from the commission to the European parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee, the committee of the regions and the European central bank, October 2010

Farhi E, Tirole J (2009) Collective moral hazard, maturity mismatch and systemic bail out. NEBR Working paper n.11698

Ferreira M, Gama PM (2005) Have world, country and industry risks changed over time? An investigation of the developed stock market volatility. J Financ Quant Anal 40:195–222

Financial Services Authority (2009) Turner review conference discussion paper. October 2009

Francis BB, Hunter DM (2004) The impact of the euro on risk exposure of the world’s major banking industries. J Int Money Finance 21:1011–1042

French KR, Schwert WG, Stambaugh RF (1987) Expected stock returns and volatility. J Financ Econ 19:3–29

Goddard J, Molyneux P, Wilson JOS, Tavakoli M (2007) European banking: an overview. J Bank Finance 31:1911–1935

Gropp R, Moerman G (2004) Measurement of contagion in bank equity prices. J Int Money Finance 23:405–459

Gropp R, Lo Duca M, Vesala J (2009) Cross-border bank contagion in Europe. International J Central Bank 5: 97:139

Haq M, Heaney R (2009) European bank equity risk: 1995–2006. J Int Financ Market Inst Money 19:274–288

Hardy DC, Nieto MJ (2011) Cross-border coordination of prudential supervision and deposit guarantees. J Financ Stab 7:155–164

Hartmann P, Straetmans S, de Vries CG (2006) Banking system stability: a cross-atlantic perspective. In: Carey M and Stulz RM (eds) The risks of financial institutions. Chicago University Press and NBER. 133–188

Houston JF, Stiroh KJ (2006) Three decades of financial sector risk. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report, 246, April 2006

IMF (2009) World economic outlook: crisis and recovery. April 2009

Kearney C, Potì V (2008) Have European Stocks become more volatile? An empirical investigation of idiosyncratic risk and market risk in the Euro area. Eur Financ Manage 14:419–444

Krimminger MH (2008) The resolution of cross-border banks: issues for deposit insurers and proposals for cooperation. J Financ Stab 4:376–390

Molyneux P, Wilson JOS (2007) Developments in European banking. J Bank Finance 31:1907–1910

Morgan DP, Rime B, Strahan PE (2004) Bank integration and state business cycles. Q J Econ 119:1555–1584

Moshirian F, Wu Q (2009) Banking industry volatility and banking crises. J Int Financ Market Inst Money 19:351–370

Outreville JF (2010) Internationalization, performance and volatility: the world largest financial groups. J Financ Serv Res 38:115–134

Schuermann T, Stiroh KJ (2006) Visible and hidden risk factors for banks. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report, 252, May 2006

Schüler M (2002) The threat of systemic risk in European banking. Q J Bus Econ 41:145–165

Schwert GW (1989) Why does stock market volatility change over time? J Finance 44:1115–1153

Schwert GW (2002) Stock volatility in the new Millennium: how wacky is Nasdaq? J Monet Econ 49:3–26

Stiroh KJ (2006) New evidence on the determinants of bank risk. J Financ Serv Res 30:237–267

Stiroh KJ (2009) Diversification in banking. In: Berger A, Molyneux P, Wilson JOS (eds) The Oxford handbook of banking. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Vogelsang T (1998) Trend function hypothesis testing in the presence of serial correlation. Econometrica 66:123–148

Vogelsang T (2001) Testing for a shift in trend when serial correlation is of unknown form. Working paper

Vulpes G, Brasili A (2006) Banking integration and co-movements in EU banks’ fragility. MIPRA paper, 1964

Wagner W (2008) The homogenization of the financial system and financial crises. J Financ Intermed 17:330–356

Wagner W (2010) Diversification at financial institutions and systemic crises. J Financ Intermed 19:373–386

Wei KCJ (1988) An asset pricing theory unifying the CAPM and APT. J Finance 43:881–892

Wei S, Zhang C (2006) Why did individual stocks become more volatile? J Bus 79:259–291

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The authors wish to thank two anonymous referees for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Appendix

Appendix

Equation (2) is derived by assuming that the return of a European index of nonfinancial firms (\( {R_{{E_{it}}}} \)), the return of an International banking industry index (\( {R_{I\_IN{D_{it}}}} \)), the return of a European banking index (\( {R_{E\_IN{D_{it}}}} \)) and the return on a Country index (\( {R_{{C_{it}}}} \)) are generated as follows:

where \( {R_{{I_{it}}}} \) is the return on an international index of nonfinancial firms and \( \varepsilon_{it}^E,\varepsilon_{it}^{I\_IND},\varepsilon_{it}^{E\_IND} \) and \( \varepsilon_{it}^C \) are mean zero error terms that are orthogonal to the right hand side variable in their respective regression and refer to country i and time t.

By replacing \( {R_{{E_{it}}}} \)in Eq. (2A) with (1A), \( {R_{{E_{it}}}} \) and \( {R_{I\_IN{D_{it}}}} \) in Eq. (3A) with (2A) and (1A), and \( {R_{{E_{it}}}} \), \( {R_{I\_IN{D_{it}}}} \), \( {R_{E\_IN{D_{it}}}} \)in Eq. (4A) with (3A), (2A) and (1A) we can also write that:

where

-

\( \theta_i^{I\_IND} = \left( {{\theta_i} + {\kappa_i}{\delta_i}} \right) \)

-

\( \varpi_i^{I\_IND} = \left( {{\varpi_i} + {\kappa_i}{\eta_i}} \right) \)

-

\( \delta_i^{E\_IND} = \left( {{\gamma_i} + {\phi_i}{\delta_i} + {\varsigma_i}\theta_i^{I\_IND}} \right), \)

-

\( \eta_i^{E\_IND} = \left( {{\lambda_i} + {\phi_i}{\eta_i} + {\varsigma_i}\varpi_i^{I\_IND}} \right), \)

-

\( {\phi_i}^{E\_IND} = \left( {{\phi_i} + {\varsigma_i}{\kappa_i}} \right) \)

-

\( \varphi_i^C = \left( {{\varphi_i} + {\omega_i}{\delta_i} + {\chi_i}\theta_i^{I\_IND} + {\psi_i}\delta_i^{E\_IND}} \right), \)

-

\( \eta_i^C = \left( {{\omega_i} + {\omega_i}{\eta_i} + {\chi_i}\varpi_i^{I\_IND} + {\psi_i}\eta_i^{E\_IND}} \right) \)

-

\( \phi_i^C = \left( {{\chi_i}{\kappa_i} + {\omega_i} + {\psi_i}{\phi_i} + {\psi_i}{\varsigma_i}{\kappa_i}} \right), \)

-

\( \chi_i^C = \left( {{\chi_i} + {\psi_i}{\varsigma_i}} \right). \)

The residuals series are, therefore, uncorrelated with our proxy for the ‘International’ market and are uncorrelated to each other.

Thus, if we denote as R it the return on a banking index that refers to country i and we assume that this return depends on the International nonfinancial, European nonfinancial, International banking industry, European banking industry and Country components as follows

where \( \beta_i^I\beta_i^E,\beta_i^{I\_IND},\beta_i^{E\_IND} \) and \( \beta_i^C \) express the sensitivity of the banking system in country i to these components, and ε it represents the unexplained residual, under the assumption that Eqs. 1A, 2A, 3A and 4A are correctly specified, we can postulate that the “true” return generating model is based on the following equationFootnote 29

where

-

\( b_i^I = \beta_i^I + \beta_i^E{\eta_i} + \beta_i^{I\_IND}\varpi_i^{I\_IND} + \beta_i^{E\_IND}\eta_i^{E\_IND} + \beta_i^C\eta_i^C; \)

-

\( b_i^E = \beta_i^E + \beta_i^{I\_IND}{\kappa_i} + \beta_i^{E\_IND}{\varphi_i}^{E\_IND} + \beta_i^C\varphi_i^C; \)

-

\( b_i^{I\_IND} = \beta_i^{I\_IND} + \beta_i^{E\_IND}{\varsigma_i} + \beta_i^C\chi_i^C; \)

-

\( b_i^{E\_IND} = \beta_i^{E\_IND} + \beta_i^C{\psi_i}; \)

-

\( b_i^C = \beta_i^C. \)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vallascas, F., Keasey, K. The Volatility of European Banking Systems: A Two-Decade Study. J Financ Serv Res 43, 37–68 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-011-0122-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-011-0122-y