Abstract

The house money effect predicts that individuals show increased risk-seeking behavior in the presence of prior windfall gains. Although the effect’s existence is widely accepted, experimental studies that compare individuals’ risk-taking behavior using house money to individuals’ risk-taking behavior using their own money produce contradictory results. This experimental field study analyzes the gambling behavior of 917 casino customers who face real losses. We find that customers who received free play at the entrance showed not higher but significantly lower levels of risk-taking behavior during their casino visit, expressed through lower average wagers. This study thus provides field evidence against the house money effect. Moreover, as a result of lower levels of risk seeking, endowed customers yield better economic results in the form of smaller own-money losses when leaving the casino.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Examples from real decision makers in businesses or casinos involving real losses are often used to motivate studies on the house money effect (see, e.g., Thaler and Johnson 1990; Arkes et al. 1994). However, evidence from field studies remains scarce. Two notable exceptions are Frino et al. (2008) as well as Hsu and Chow (2013). Both studies use data from professional investors and find that the house money effect is present as the riskiness of investments is higher in the presence of prior gains. However, these studies do not address the fact that investors who are investing prior gains are not a random selection of the entire population of investors. Thus, their attitude towards risk might be systematically different from those investors who do not have prior gains.

The experiment was conducted with CHF, and therefore, we will refer to all monetary values in CHF in the course of the paper. Fortunately, at the time of the experiment, CHF 1 exchanged for about USD 1. Thus, all CHF values can also be read as USD.

Of all casino customers, approximately 2% were chosen to participate in the study. The only limitation was that customers who were selected on one visit were excluded from selection in any subsequent visit.

In line with the first control group, the participants in the second control group were also randomly selected.

It is important to note that all participants in our treatment and control groups were aware that their behavior could be monitored by the casino. Indeed, in Switzerland, regulation obliges casino operators to comply with social welfare provisions and to ensure that no individual gambles to the extent that he or she is at risk of going broke, i.e., risking personal bankruptcy (Meyer 2009). This reduces the risk of compulsive gambling because all gamblers in Switzerland, and thus our participants, are protected by law.

Because croupiers monitor gambling behavior as a regular task in their everyday work, they have sufficient experience at fulfilling this task for the data collection of this experiment. Indeed, croupiers and game floor managers typically monitor gambling behavior in order to secure an impeccable gambling flow.

Only participants who received an endowment and used it on the initial day belonged to the treatment group. Our data showed that 579 (97.3%) of all participants used their endowment on the initial day. The other 16 (2.7%) were excluded from the data set.

McGlothin (1956) used the amount wagered to investigate the risk-taking behavior of individuals at the race track. Gertner (1993) analyzed how much contestants of the game show “Card Sharks” wagered in positive expected-value gambles and constructed a measure for risk aversion. Gneezy and Potters (1997) provided their participants with an endowment which they could either keep or bet in various rounds and subsequently analyzed the average bet their participants made. Haigh and List (2005) compared the betting patterns, i.e., the average amount bet, between professional traders and undergraduate students to analyze each group’s attitude towards risk.

The numbers shown for the variable result are also in line with reports of other institutions. The American Gaming Association (2013, p. 33) showed that a majority of casino visitors sets a budget of approximately 100 USD per casino visit, while 30% gamble on a budget of 100–300 USD.

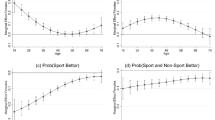

The difference between control groups I and II is insignificant when using a t test but significant when using a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Thus, playing the wheel of fortune but not winning anything also has an effect on subsequent risk-taking. Indeed, this finding reinforces our main results because those subjects who started their casino experience by “losing”, i.e., not winning on the wheel of fortune, went on to wager more than those who started gambling without having played the wheel of fortune. In turn, those who did not play the wheel of fortune went on to wager more than those subjects who started their casino experience by winning on the wheel of fortune.

Instead of the cumulative number of games, we alternatively also include the cumulative time played by each subject as a control variable in our OLS estimations. We find that our results remain unchanged.

In those sessions classified as treatment house money the amount of house money, on average, corresponds to 33% of the total money wagered in that session.

For 14 out of 579 players in the treatment group, the information on their house money wager was missing, although their record shows that they used their coupons. As 90% of the other 565 players used their coupons in the first session, we assume that the 14 players also used their coupons in the first session. However, our results do not change if we exclude these 14 players from our analyses.

Wald test for equality of coefficients: column (3): F(1764) = 2.79; Prob. >F = 0.10, column (4): F(1730) = 4.65; Prob. >F = 0.03).

Wald test for equality of coefficients: column (5): F(1764) = 9.10; Prob. >F = 0.00, column (6): F(1730) = 10.15; Prob. >F = 0.00).

This is confirmed if we run a t test and a Wilcoxon rank-sum test between those who received CHF 5 and both control groups. Both tests are statistically significant at the 5% level.

We subtract the house money amount only for participants who left the casino with a loss. For those who left the casino with a win, the net win is equal to the net win own money. The adjustment is performed only for those participants who lost money because we are interested in the specific amount of money that came from the participants’ self-earned money. Thus, in the case that a participant left the casino with a win, the adjustment is redundant.

Table 6 with all standard errors, as well as t test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test statistics, can be found in the “Appendix”. The table further shows that the difference between both control groups is not statistically significant. If the tests are rerun on the variable net win own money, all tests between the control and treatment group are statistically significant.

Although Peng et al. (2013) presented results in line with the house money effect, they also challenged the validity of the quasi-hedonic editing rule.

Harrison’s (2007) analysis made two key improvements on the initial analysis by Clark (2002). First, Harrison (2007) differentiated between the treatment effect on the proportion of those not willing to contribute anything and the treatment effect on the amount contributed conditional on contributing. Second, to control for panel effects, Harrison (2007) used generalized estimating equations to analyze the data.

Reconsidering our introductory example, the two-stage gamble would then be evaluated as “a 50% chance to win $70 and a 50% chance to win $30”, which is typically less attractive than a sure win of $50 and thus leads to risk-averse behavior.

References

Ackert, L., Charupat, N., Church, B. K., & Deaves, R. (2006). An experimental examination of the house money effect in a multi-period setting. Experimental Economics, 9(1), 5–16.

Aloysius, J. A. (2003). Rational escalation of costs by playing a sequence of unfavorable gambles: The martingale. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 51(1), 111–129.

American Gaming Association. (2013). State of the states: The AGA survey of casino entertainment. Washington, DC: American Gaming Association.

Arkes, H. R., & Blumer, C. (1985). The psychology of sunk cost. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 35(1), 124–140.

Arkes, H. R., Joyner, C., Pezzo, M., Nash, J. G., Siegel-Jacobs, K., & Stone, E. (1994). The psychology of windfall gains. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 59(3), 331–347.

Barberis, N. (2012). A model of casino gambling. Management Science, 58(1), 35–51.

Battalio, R., Kagel, J., & Jiranyakul, K. (1990). Testing between alternative models of choice under uncertainty: Some initial results. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 3(1), 25–50.

Beltramini, R. F. (2000). Exploring the effectiveness of business gifts: Replication and extension. Journal of Advertising, 29(2), 75–78.

Cárdenas, J. C., De Roux, N., Jaramillo, C. R., & Martinez, L. R. (2014). Is it my money or not? An experiment on risk aversion and the house-money effect. Experimental Economics, 17(1), 47–60.

Chau, A., & Phillips, J. (1995). Effects of perceived control upon wagering and attributions in computer blackjack. The Journal of General Psychology, 122(3), 253–269.

Cherry, T. L., Kroll, S., & Shogren, J. F. (2005). The impact of endowment heterogeneity and origin on public good contributions: Evidence from the lab. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 57(3), 357–365.

Clark, J. (2002). House money effects in public good experiments. Experimental Economics, 5(3), 223–231.

Croson, R., & Sundali, J. (2005). The gambler’s fallacy and the hot hand: Empirical data from casinos. The Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 30(3), 195–209.

Etchart-Vincent, N., & l’Haridon, O. (2011). Monetary incentives in the loss domain and behavior toward risk: An experimental comparison of three reward schemes including real losses. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 42(1), 61–83.

Falk, A. (2007). Gift exchange in the field. Econometrica, 75(5), 1501–1511.

Frino, A., Grant, J., & Johnstone, D. (2008). The house money effect and local traders on the Sydney Futures Exchange. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 16(1), 8–25.

Gärling, T., & Romanus, J. (1997). Integration and segregation of prior outcomes in risky decisions. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 38(4), 289–296.

Gertner, R. (1993). Game shows and economic behavior: Risk-taking on “Card Sharks”. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(2), 507–521.

Gneezy, U., & Potters, J. (1997). An experiment on risk taking and evaluation periods. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(2), 631–645.

Haigh, M. S., & List, J. A. (2005). Do professional traders exhibit myopic loss aversion? An experimental analysis. The Journal of Finance, 60(1), 523–534.

Haisley, E., & Loewenstein, G. (2011). It’s not what you get but when you get it: The effect of gift sequence on deposit balances and customer sentiment in a commercial bank. Journal of Marketing Research, 48(1), 103–115.

Harrison, G. W. (2007). House money effects in public good experiments: Comment. Experimental Economics, 10(4), 429–437.

Houser, D., & Xiao, E. (2015). House money effects on trust and reciprocity. Public Choice, 163(1–2), 187–199.

Hsu, Y. L., & Chow, E. H. (2013). The house money effect on investment risk taking: Evidence from Taiwan. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 21(1), 1102–1115.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–292.

Keasey, K., & Moon, P. (1996). Gambling with the house money in capital expenditure decisions: An experimental analysis. Economics Letters, 50(1), 105–110.

McGlothin, W. (1956). Stability of choices among uncertain alternatives. The American Journal of Psychology, 69(4), 604–615.

Meyer, G. (2009). Problem gambling in Europe: Challenges, prevention, and interventions. New York: Springer.

Narayanan, S., & Manchanda, P. (2012). An empirical analysis of individual level casino gambling behavior. Quantitative Marketing and Economics, 10(1), 27–62.

Peng, J., Miao, D., & Xiao, W. (2013). Why are gainers more risk seeking. Judgment and Decision Making, 8(2), 150–160.

Rabin, M. (2002). Inference by believers in the law of small numbers. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(3), 775–816.

Staw, B. M. (1976). Knee-deep in the big muddy: A study of escalating commitment to a chosen course of action. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16(1), 27–44.

Thaler, R. H., & Johnson, E. J. (1990). Gambling with the house money and trying to break even: The effects of prior outcomes on risky choice. Management Science, 36(6), 643–660.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science, 211(5), 453–458.

Weber, M., & Zuchel, H. (2005). How do prior outcomes affect risk attitude? Comparing escalation of commitment and the house-money effect. Decision Analysis, 2(1), 30–43.

Whyte, G. (1986). Escalating commitment to a course of action: A reinterpretation. Academy of Management Review, 11(2), 311–321.

Whyte, G. (1993). Escalating commitment in individual and group decision making: A prospect theory approach. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 54(3), 430–455.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rüdisser, M., Flepp, R. & Franck, E. Do casinos pay their customers to become risk-averse? Revising the house money effect in a field experiment. Exp Econ 20, 736–754 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-016-9509-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-016-9509-9