Abstract

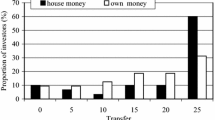

We experimentally investigate to what extent people trust and honor trust when they are playing with other people’s money (OPM). We adopt the well-known trust game by Berg et al. (in Games Econ. Behav. 10:122–142, 1995), with the difference that the trustor (sender) who sends money to the trustee (receiver) does this on behalf of a third party. We find that senders who make decisions on behalf of others do not behave significantly different from senders in our baseline trust game who manage their own money. But receivers return significantly less money when senders send a third party’s money. As a result, trust is only profitable in the baseline trust game, but not in the OPM treatment. The treatment effect among the receivers is gender specific. Women return significantly less money in OPM than in baseline, while there is no such treatment effect among men. Moreover, women return significantly less than men in the OPM treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We use the term “client” in the experiment, but in a principal-agent framework, the client is the principal, while the sender is her agent.

Hamman et al. (2010) find that delegation may increase profit also in the absence of such punishment reduction mechanisms. They show that a principal may hire an agent to take self-interested actions that he or she would be reluctant to take themselves.

Positive reciprocity on behalf of others is also studied by Song (2008), but in a trust game where both senders and receivers make decisions on behalf of a group. Like us, she finds less reciprocity, but this is mainly attributed to the relationship between the receiver and the group he/she is making decisions for.

Only one study, Bellemare and Kröger (2007), finds that men are more reciprocal than women. Some studies found no gender differences in reciprocal behavior (Clark and Sefton 2001; Cox and Deck 2006; Eckel and Wilson 2004a, 2004b; Bohnet 2007; Migheli 2007; Innocenti and Pazienza 2006; Slonim and Guillen 2010), while quite a few studies have found that women are more reciprocal than men (Croson and Buchan 1999; Chaudhuri and Gangadharan 2007; Snijders and Keren 2001; Buchan et al. 2008; Schwieren and Sutter 2008; Ben-Ner et al. 2004; Eckel and Grossman 1996).

If, on the other hand, the receiver is sensitive to inequality between other players, one could see treatment differences. But the direction of the treatment effects is not straight forward to predict, and would depend upon (among other things) the salary of the sender.

Formally, Falk and Fischbacher (2006) defines the kindness term,φ j , as a product of outcomes and intentions, where both outcomes and intentions are functions of player j’s actions, the beliefs of player i about the strategy of player j as well as i’s belief about j’s belief about i’s strategy. See also Dufwenberg and Kirchsteiger (2004).

See Charness and Rabin (2002)’s conceptual model of social preferences, where agent i’s utility is a weighted sum of his own material payoff and the material payoff of player j, and where the weight on player j’s payoff depends both on distributional and reciprocal preferences.

Note that if the sender cares about his or her client, and the receiver knows this, then he may return money to the client in order to increase the utility of the sender. For the utility function of player i to account for this, one must replace the monetary payoff of player j with the utility of player j (at least in the reciprocity term). However, this will complicate the analysis.

In our experiment, the clients were not even in the room, making them less entitled to money. This fact may also affect the kindness term,φ j .

References

Agranov, M., Bisin, A., & Schotter, A. (2010). Other people’s money: an experimental study of the impact of the competition for funds. Working Paper, New York University.

Bartling, B., & Fischbacher, U. (2012). Shifting the blame: on delegation and responsibility. Review of Economic Studies, 79(1), 67–87.

Bellemare, C., & Kröger, S. (2007). On representative social capital. European Economic Review, 5, 183–202.

Ben-Ner, A., Kong, F., Putterman, L., & Magan, D. (2004). Reciprocity in a two-part dictator game. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 53(3), 333–352.

Berg, J., Dickhaut, J., & McCabe, K. (1995). Trust, reciprocity, and social history. Games and Economic Behavior, 10, 122–142.

Bohnet, I. (2007). Why women and men trust others. In B. S. Frey & A. Stutzer (Eds.), Economics and psychology. A promising new cross-disciplinary field. Cambridge and London: MIT Press.

Bohnet, I., & Zeckhauser, R. (2004). Trust, risk and betrayal. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 55(4), 467–484.

Bolton, G. E., & Ockenfels, A. (2000). ERC: a theory of equity, reciprocity and competition. The American Economic Review, 90, 166–193.

Brandts, J., & Sola, C. (2001). Reference points and negative reciprocity in simple sequential games. Games and Economic Behavior, 36, 138–157.

Buchan, N., Croson, R., & Solnick, S. (2008). Trust and gender: an examination of behavior and beliefs in the investment game. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 68, 466–476.

Chakravarty, S., Harrison, G., Haruvy, E., & Rutström, E. (2011). Are you risk averse over other people’s money? Southern Economic Journal, 77(4), 901–913.

Charness, G., & Jackson, M. (2008). The role of responsibility in strategic risk-taking. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 69, 241–247.

Charness, G., & Levine, D. I. (2007). Intention and stochastic outcomes: an experimental study. The Economic Journal, 117, 1051–1072.

Charness, G., & Rabin, M. (2002). Understanding social preferences with simple tests. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(3), 817–869.

Chaudhuri, A., & Gangadharan, L. (2007). An experimental analysis of trust and trustworthiness. Southern Economic Journal, 73(4), 959–985.

Clark, K., & Sefton, M. (2001). The sequential prisoner’s dilemma: evidence on reciprocation. The Economic Journal, 111, 51–68.

Coffman, L. C. (2011). Intermediation reduces punishment (and reward). American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 3(4), 77–106.

Cox, J. C., & Deck, C. (2006). When are women more generous than men? Economic Inquiry, 44, 587–598.

Croson, R., & Buchan, N. (1999). Gender and culture: international experimental evidence from trust games. The American Economic Review, 89(2), 386–391.

Croson, R., & Gneezy, U. (2009). Gender differences in preferences. Journal of Economic Literature, 47, 1–27.

Dufwenberg, M., & Kirchsteiger, G. (2004). A theory of sequential reciprocity. Games and Economic Behavior, 47, 268–298.

Eckel, C., & Grossman, P. (1996). The relative price of fairness: gender differences in a punishment game. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 30, 143–158.

Eckel, C., & Wilson, R. (2004a). Conditional trust: sex, race and facial expressions in a trust game. Working Paper, Virginia Tech.

Eckel, C., & Wilson, R. (2004b). Whom to trust? Choice of partner in a trust game. Working Paper, Virginia Tech.

Eriksen, K., & Kvaløy, O. (2010). Myopic investment management. Review of Finance, 14(3), 521–542.

Falk, A., & Fischbacher, U. (2006). A theory of reciprocity. Games and Economic Behavior, 54, 293–315.

Falk, A., Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2003). On the nature of fair behavior. Economic Inquiry, 41(1), 20–26.

Fehr, E., & Gächter, S. (2000). Fairness and retaliation: the economics of reciprocity. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14(3), 159–181.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114, 817–868.

Fehr, E., Kirchsteiger, G., & Riedl, A. (1993). Does fairness prevent market clearing? An experimental investigation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(2), 437–460.

Fershtman, C., & Gneezy, U. (2001). Strategic delegation: an experiment. The Rand Journal of Economics, 32(2), 352–368.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). Z-tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10, 171–178.

Hamman, J. R., Loewenstein, G., & Weber, R. A. (2010). Self-interest through delegation: an additional rationale for the principal-agent relationship. The American Economic Review, 100(4), 1826–1846.

Innocenti, A., & Pazienza, M. (2006). Altruism and gender in the trust game. Working paper, University of Sienna.

McCabe, K., & Smith, V. (2000). Goodwill accounting in economic exchange. In G. Gigerenzer & R. Selten (Eds.), Bounded rationality: the adaptive toolbox. Cambridge: MIT Press.

McCabe, K., Rigdon, M., & Smith, V. (2003). Positive reciprocity and intentions in trust games. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 52(2), 267–275.

Migheli, M. (2007). Trust, gender, and social capital: experimental evidence from three western European countries. Working Paper, University of Turin and Catholic University of Leuven.

Offerman, T. (2002). Hurting hurts more than helping helps. European Economic Review, 46, 1423–1437.

Rabin, M. (1993). Incorporating fairness into game theory and economics. The American Economic Review, 83(5), 1281–1302.

Reynolds, D., Joseph, J., & Sherwood, R. (2009). Risky shift versus cautious shift: determining differences in risk taking between private and public management decision-making. Journal of Business Economics Research, 7(1), 63–78.

Schwieren, C., & Sutter, M. (2008). Trust in cooperation or ability? An experimental study on gender differences. Economics Letters, 99(3), 494–497.

Slonim, R., & Guillen, P. (2010). Gender selection discrimination: evidence from a trust game. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 76, 385–405.

Snijders, C., & Keren, G. (2001). Do you trust? Whom do you trust? When do you trust? Advances in Group Processes, 18, 129–160.

Song, F. (2008). Trust and reciprocity behavior and behavioral forecasts: individuals versus group-representatives. Games and Economic Behavior, 62(2), 675–696.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We would like to thank the Editor, two referees and Jim Andreoni, Alexander Cappelen, Gary Charness, Kristoffer Eriksen, Åshild Johnsen, Klaus Mohn, Mari Rege, Bettina Rochenbach and participants at the Nordic conference on Behavioral and Experimental Economics in Lund, the International Meeting on Experimental and Behavioral Economics in Castellón, the ESA Meeting in Xiamen and the ESA meeting in Tucson for helpful comments and discussions. Financial support from the Norwegian Research Council is greatly appreciated.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kvaløy, O., Luzuriaga, M. Playing the trust game with other people’s money. Exp Econ 17, 615–630 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-013-9386-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-013-9386-4