Abstract

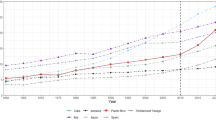

European Union (EU) enlargements in 2004 and 2007 were accompanied by increased migration from new-accession to established-member (EU-15) countries. The impacts of these flows depend, in part, on the amount of time that persons from the former countries live in the latter over the life course. In this paper, we develop period estimates of duration expectancy in EU-15 countries among persons from new-accession countries. Using a newly developed set of harmonized Bayesian estimates of migration flows each year from 2002 to 2008 from the Integrated Modelling of European Migration Project, we exploit period age patterns of country-to-country migration and mortality to summarize the average number of years that persons from new-accession countries could be expected to live in EU-15 countries over the life course. In general, the results show that the amount of time that persons from new-accession countries could be expected to live in the EU-15 nearly doubled after 2004.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia joined the EU in 2004. Bulgaria and Romania joined the EU in 2007. Although the focus of this paper is with EU expansions in 2004 and 2007, Croatia joined the EU in 2013, bringing the total number of new-accession countries to 13.

t sub/superscripts are omitted from the notation below, but are nonetheless implied.

The correlation between our estimates of life expectancy at birth and those provided by the World Bank is 0.93.

An alternative approach might be to summarize medians and quartiles. We summarize means and standard errors because the distributions of the quantities in (1) are not badly skewed and the tails are not especially heavy. Readers can verify this for any/all distributions of interest, as the full set of estimates for each pair of new-accession and EU-15 countries each year from 2002 to 2008 is provided in the online appendix.

The full set of estimates for each pair of new-accession and EU-15 countries each year from 2002 to 2008 is provided in the online appendix.

This is also reflected in the age-specific transition probabilities (not shown).

As a quality check, we increased the number of random draws to 1000 to ensure that our 100 random draws of age-specific country-to-country migration counts for each year capture the range of the full posterior distributions. The resulting distributions are virtually identical.

We constructed similar figures to those shown in Fig. 6 for each pair of new-accession and EU-15 countries. Generally, the degree of uncertainty in our estimates of duration expectancy is relatively more pronounced for country-pairs wherein the destination country is the United Kingdom, which, ultimately, reflects greater uncertainty in counts of age-specific migration to the United Kingdom in the IMEM estimates.

Recall from our earlier discussion that when the model is run for a single birth cohort (i.e., a birth cohort in a single new-accession country), the size of the birth cohort is arbitrary. However, when multiple birth cohorts are simultaneously considered in the same model, it is necessary to adjust model inputs so that the size of each birth cohort is proportional to the observed distribution across countries.

References

Abel, G. J. (2010). Estimation of international migration flow tables in Europe. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A, 173(4), 797–825.

Aleksynska, M. (2011). Civic participation of immigrants in Europe: Assimilation, origin, and destination country effects. European Journal of Political Economy, 27(3), 566–585.

Barrell, R., Fitzgerald, J., & Riley, R. (2010). EU enlargements and migration: Assessing the macroeconomic impacts. Journal of Common Market Studies, 48(2), 373–395.

Barrett, A. (2010). EU enlargement and Ireland’s labor market. In M. Kahanec & K. F. Zimmermann (Eds.), EU labor markets after post-enlargement migration (pp. 145–162). Berlin: Springer.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Lawton, H. (2008). The impact of the recent expansion of the EU on the UK labour market. IZA Discussion Paper No. 3695, Institute for the Study of Labor, Bonn. http://ftp.iza.org/dp3695.pdf. Accessed 12 May 2015.

Boeri, T., & Brücker, H. (2001). Eastern enlargements and EU-labour markets: Perceptions, challenges and opportunities. IZA Discussion Paper No. 256, Institute for the Study of Labor, Bonn. http://ftp.iza.org/dp256.pdf. Accessed 12 May 2015.

Brücker, H., & Damelang, A. (2009). Labour mobility within the EU in the context of enlargement and the functioning of the transitional arrangements: Analysis of the scale, direction and structure of labour mobility. VC/2007/0293 Deliverable 2, Institute for Employment Research, Nürnberg. http://doku.iab.de/grauepap/2009/LM_Deliverable_2.pdf. Accessed 12 May 2015.

De Valk, H. A. G., Windzio, M., Wingens, M., & Aybek, C. (2011). Immigrant settlement and the life course: An exchange of research perspectives and outlook for the future. In M. Wingens, M. Windzio, H. A. G. de Valk, & C. Aybek (Eds.), A life-course perspective on migration and integration (pp. 283–297). Dordrecht: Springer.

DeWaard, J. (2013). Compositional and temporal dynamics of international migration in the EU/EFTA: A new metric for assessing countries’ immigration and integration policies. International Migration Review, 47(2), 249–295.

DeWaard, J. (2015). Beyond group-threat: Temporal dynamics of international migration and linkages to anti-foreigner sentiment. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(7), 1041–1067.

DeWaard, J., & Raymer, J. (2012). The temporal dynamics of international migration: Recent trends. Demographic Research, 26(21), 543–592.

Dustmann, C., & Weiss, Y. (2007). Return migration: Theory and empirical evidence from the UK. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 45(2), 236–256.

Geddes, A., Niessen, J., Balch, A., Bullen, C., & Peiro, M. J. (2005). European civic citizenship and inclusion index. Manchester: British Council and Migration Policy Group.

Goldstein, S. (1964). The extent of repeated migration: An analysis based on the Danish population register. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 59(108), 1121–1132.

Green, A. E., Owen, D., & Jones, P. (2007). The economic impact of migrant workers in the West Midlands. Full Report, Institute for Employment Research, University of Warwick. http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/ier/publications/2007/green_et_al_2007_lsc.pdf. Accessed 12 May 2015.

Greenwood, M. J. (1997). Internal migration in developed countries”. In M. R. Rozenzweig & O. Stark (Eds.), Handbook of population and family economics (pp. 647–720). New York: Elsevier.

Huddleston, T., Niessen, J., Chaoimh, E. N., & White, E. (2011). Migrant integration policy index III. Manchester: British Council and Migration Policy Group.

Kahanec, M., Zaiceva, A., & Zimmermann, K. F. (2010). Lessons from migration after EU enlargement. In M. Kahanec & K. F. Zimmermann (Eds.), EU labor markets after post-enlargement migration (pp. 3–45). Berlin: Springer.

Kahanec, M., & Zimmermann, K. F. (Eds.). (2010). EU labor markets after post-enlargement migration. Berlin: Springer.

Kim, K., & Cohen, J. E. (2010). Determinants of international migration flows to and from industrialized countries: A panel data approach beyond gravity. International Migration Review, 44(4), 899–932.

Kupiszewska, D., & Kupiszewski, M. (2005). A revision of the traditional multiregional model to better capture international migration: The multipoles model and its application. CEFMR Working Paper 10/2005. Central European Forum for Migration Research, Warsaw. http://www.cefmr.pan.pl/docs/cefmr_wp_2005-10.pdf. Accessed 2 Dec 2015.

Kupiszewska, D., & Nowok, B. (2008). Comparability of statistics on international migration flows in the European Union. In J. Raymer & F. Willekens (Eds.), International migration in Europe: Data, models and estimates (pp. 41–72). Chichester: Wiley.

Le Grand, C., & Szulkin, R. (2002). Permanent disadvantage or gradual integration: Explaining the immigrant-native earnings gap in Sweden. Labour, 16(1), 37–64.

Malmusi, D., Borrell, C., & Benach, J. (2010). Migration-related health inequalities: Showing the complex interactions between gender, social class and place of origin. Social Science and Medicine, 71(9), 1610–1619.

Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A., & Taylor, J. E. (1998). Worlds in motion: Understanding international migration at the end of the millennium. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Mladovsky, P. (2009). A framework for analysing migrant health policies in Europe. Health Policy, 93(1), 55–63.

Niessen, J., Huddleston, L., Citron, L., Geddes, A., & Jacobs, D. (2007). Migrant integration policy index II. Manchester: British Council and Migration Policy Group.

Nowok, B., Kupiszewska, D., & Poulain, M. (2006). Statistics on international migration flows. In M. Poulain, N. Perrin, & A. Singleton (Eds.), THESIM: Towards harmonised European statistics on international migration (pp. 203–232). Louvain-la-Neuve: UCL Presses Universitaires de Louvain.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2008). A profile of immigrant populations in the 21st century: Data from OECD countries. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Palloni, A. (2001). Increment-decrement life tables. In S. H. Preston, P. Heuveline, & M. Guillot (Eds.), Demography: Measuring and modelling population processes (pp. 256–273). Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Paul, A. M. (2011). Stepwise international migration: A multistage migration pattern for the aspiring migrant. American Journal of Sociology, 116(6), 1842–1886.

Poulain, M., Perrin, N., & Singleton, A. (2006). THESIM: Towards harmonized European statistics on international migration. Louvain-la-Neuve: UCL Presses Universitaires de Louvain.

Quinn, E. (2011). Temporary and circular migration: Ireland. Report, The Economic and Social Research Institute, European Migration Network Ireland.

Raymer, J., Wiśniowski, A., Forster, J. J., Smith, P. W. F., & Bijak, J. (2013). Integrated modeling of European migration. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 108(503), 801–819.

Rogers, A. (1975). Introduction to multiregional mathematical demography. New York: Wiley.

Rogers, A. (1995). Multiregional demography: Principles, methods and extensions. London: Wiley.

Schoen, R. (1975). Constructing increment-decrement life tables. Demography, 12(2), 313–324.

Schoen, R. (1988). Modeling multigroup populations. New York: Pleneum.

Sumption, M., & Somerville, W. (2010). The UK’s new Europeans: Progress and challenges five years after accession. Policy Report, Equality and Human Rights Commission and Migration Policy Institute. http://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/new_europeans.pdf. Accessed 12 May 2015.

Toma, S., & Castagnone, E. (2014). Following in the footsteps of others? A life-course perspective on mobility trajectories and migrant networks among Senegalese migrants. Paper presented at Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America. San Diego, CA. May 1-3.

Van Tubergen, F. (2004). Occupational status of immigrants in cross-national perspective: A multilevel analysis of seventeen Western societies. In C. A. Parsons & T. M. Smeeding (Eds.), Immigration and the transformation of Europe (pp. 147–171). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vono-de-Vilhena, D., & Bayona-Carrasco, J. (2012). Transition towards homeownership among foreign-born immigrants in Spain from a life-course approach. Population, Space and Place, 18(1), 100–115.

White, A. (2011). Polish families and migration since EU accession. Bristol: The Policy Press.

Wiśniowski, A., Bijak, J., Christiansen, S., Forster, J. J., Keilman, N., Raymer, J., & Smith, P. W. F. (2013). Utilising expert opinion to improve the measurement of international migration in Europe. Journal of Official Statistics, 29(4), 583–607.

Wiśniowski, A., Forster, J. J., Smith, P. W. F., Bijak, J., & Raymer, J. (2016). Integrated modelling of age and sex patterns of European migration. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A (Statistics in Society). doi:10.1111/rssa.12177

Wright, M., & Bloemraad, I. (2012). Is there a trade-off between multiculturalism and socio-political integration? Policy regimes and immigrant incorporation in comparative perspective. Perspectives on Politics, 10(1), 77–95.

Zaiceva, A., & Zimmermann, K. F. (2012). Returning home at times of trouble? Return migration of EU enlargement migrants during the crisis. IZA Discussion Paper No. 7111, Institute for the Study of Labor, Bonn. http://ftp.iza.org/dp7111.pdf. Accessed 12 May 2015.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by center Grant #R24 HD041023 awarded to the Minnesota Population Center at the University of Minnesota by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and by research funds awarded to DeWaard by the Life Course Center at the University of Minnesota. The age-specific migration data used in this paper were estimated as part of the Integrated Modelling of European Migration (IMEM) Project, www.imem.cpc.ac.uk, funded by the New Opportunities for Research Funding Agency Co-operation in Europe (NORFACE), 2009–2012. The authors wish to thank the Editor and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

DeWaard, J., Ha, J.T., Raymer, J. et al. Migration from New-Accession Countries and Duration Expectancy in the EU-15: 2002–2008. Eur J Population 33, 33–53 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-016-9383-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-016-9383-3