Abstract

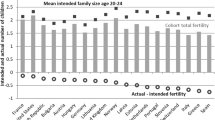

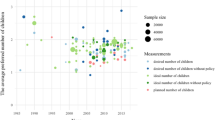

Combining the data of the 1986–2001 Microcensus surveys, I reconstruct trends in fertility intentions across time and over the life course of Austrian women born since the 1950s. Young adults in Austria expressed fertility intentions that were below the replacement-level threshold as early as in 1986 and women born since the mid-1950s consistently desired fewer than two children on average throughout their reproductive lives. A two-child family norm, however, still clearly dominates the fertility intentions of different age, cohort and education groups. Uncertainty about childbearing intentions is rather common, especially among younger and childless respondents. Different assumptions about reproductive preferences of undecided respondents affect estimates of the mean intended family size. Although Austrians were among the first in Europe to express low fertility intentions, their position is no longer unique. By the early 2000s, young women in a number of other European countries also expressed sub-replacement fertility intentions.

Résumé

A partir des données des enquêtes de Microcensus de la période 1986–2001, nous avons reconstruit l’évolution dans le temps et au cours de la biographie des intentions de fécondité des femmes autrichiennes nées dans les années 50. Les jeunes adultes en Autriche exprimaient déjà des intentions de fécondité inférieures au seuil de remplacement dès 1986, et les femmes nées au milieu des années 50 souhaitaient moins de deux enfants en moyenne tout au long de leur vie reproductive. Une norme de deux enfants par famille domine toutefois clairement les intentions de fécondité des différents groupes d’âge, de cohorte et de niveau d’éducation. L’incertitude à propos des intentions de fécondité est plutôt répandue, en particulier parmi les enquêtés jeunes et sans enfant. Les hypothèses concernant les préférences des enquêtés indécis conditionnent les estimations de la taille souhaitée de famille. Bien que les autrichiens aient été les premiers à exprimer des intentions de fécondité basses, leur situation n’est plus unique: au début des années 2000, les jeunes femmes d’un certain nombre d’autres pays européens avaient des intentions de fécondité inférieures au seuil de remplacement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Regretfully, Microcensus surveys do not provide information about fertility ideals. As a result, the frequently reported fall in family size ideals in Austria deep below replacement level (Goldstein et al. 2003; Testa 2007) cannot be analysed here. Similarly, due to lack of data on men, Microcensus data cannot corroborate the Eurobarometer findings on the extreme low family size ideals among Austrian men (Testa 2006).

Frequently, fertility intentions and desires have distinct meanings, with desires referring to the number of children respondents would like to have in their lives (see McClelland 1983, pp. 296–298 for different specifications) and intentions reflecting a “determination to act in a certain way” (Morgan 2001, p. 154). In other words, intentions represent a measure where respondents take into account actual and expected constraints that may prevent them from realising their desires. The German word [Kinder]Wunsch, used in the analysed Microcensus surveys, is commonly translated as a desire or a wish. However, in the absence of an established German term for fertility intentions, Kinderwunsch is also commonly translated as childbearing intention.

More information is provided in German at http://www.statistik.at/web_de/frageboegen/private_haushalte/mikrozensus/index.html.

Questions on fertility intentions were also asked in 1976 and 1981, but only married women were included. These data are not comparable with the more recent surveys and are not analysed here.

These proxy responses, i.e. responses of the reference persons on behalf of other persons in the household are commonly included in the Microcensus surveys, for instance in the case of mothers replying on behalf of their young adult daughters still living in the parental home. Moreover, these responses are problematic and prone to misinterpretations of other people’s intentions.

In the 2001 survey organisers decided not to accept proxy responses in the intentions module and instructed the interviewers to contact eligible respondents who could not be reached in person later by phone (Kytir et al. 2002, p. 840; Klapfer 2003, p. 826). However, the dataset does not make it possible to ascertain whether most of the responses coded as proxy interviews in 2001 were indeed conducted by phone with the respondents themselves. Consequently, I decided to eliminate all the possible proxy interviews from the 2001 dataset as well.

For instance, in the 2001 survey 18% of the valid interviews in the intentions module (i.e. those excluding the respondents who did not respond to the intentions questions) were provided by proxy persons. This share was only 11% among the respondents with children and reached 30% among the childless. At age 20–25, 34% of responses were proxy interviews.

The incompatibility of the 2006 survey with previous waves is also signalled by the higher than expected levels of completed fertility among the respondents. Three possible causes of such incompatibility can be identified. First, in contrast with previous surveys, the set of questions on fertility intentions in 2006 started with an opening statement suggesting that there are too few children born in Austria: “The question on childbearing desires gives an opportunity, among other things, to better estimate whether the trend towards too low numbers of children will continue or whether we may expect increasing numbers of births in the years to come” (author’s translation). This statement might have encouraged respondents to express higher fertility desires. Second, the 2006 survey was conducted by phone, whereas the previous surveys were conducted by face-to-face interviews. Third, markedly fewer respondents expressed uncertainty about their intentions in 2006 (6.3%). It appears that unlike in previous surveys the interviewers in the 2006 survey had not offered respondents the explicit option of expressing uncertainty.

Within the category of women with tertiary education it would be useful to look separately at women with education provided by universities of applied science primarily training teachers and social workers. Their fertility is considerably higher and their childlessness is lower than among women with full university education (Spielauer 2005; Prskawetz et al. 2008). However, the sample size of the Microcensus does not allow such a distinction for different age (cohort) categories.

According to OECD (2005), 18.3% of Austrians were enrolled in education at age 25, of whom only 2.3% were enrolled in lower than tertiary education. Enrolment in education dropped to 6.7% at age 29.

The age and parity composition of the female population was estimated from the 1991 Census results combined with the vital statistics on births by age of mother and birth order of child prior and after the date of the 1991 Census (see Prskawetz et al. 2008 for more details).

Finer specifications can be adopted as well. For instance, the low and the high values of the range distributions of the undecided respondents can provide further sub-variants to the medium variant (see Smallwood and Jefferies (2003) for a discussion of similar assumptions in England and Wales).

This estimation was broadly in agreement with the findings in the other rounds of the survey and has not resulted in any obvious inconsistencies in trends over time, across cohorts, and age groups.

A preference for larger-family size is similarly uncommon in the Czech Republic where according to the 2005 Generations and Gender Survey only 14% of women aged 18–24 intended to have three or more children (Sobotka et al. 2008, Table 7).

After controlling for selected factors (age, employment, partnership status, and the indicators of the value of children), van Peer and Rabušic (2008) found that higher-educated men and women were less likely to prefer small family sizes (0 or 1 child) than their lower-educated counterparts.

Earlier surveys of fertility desires in Austria, then conducted among married women only, did not detect any differences in fertility desires for women with higher than primary education. In 1978 married Austrian women of reproductive age with higher than primary education desired between 2.06 and 2.11 children on average (Institut für Demographie 1980, p. 138, Table A.2.6). However, differences in the proportion of married women among education groups as well as the lacking data for unmarried women make these results incomparable with my analysis.

Comparability of results for these countries may be affected by using different data sources, different surveys and also by the differences in the questions on fertility intentions. Also the choice of uncertainty, when allowed, hinders this comparability. Nevertheless, these methodological issues do not affect general conclusions on the spread of sub-replacement family desires.

References

Berrington, A. (2004). Perpetual postponers. Women’s, men’s and couples’ fertility intentions and subsequent fertility behaviour. Population Trends, 117(Autumn 2004), 9–19.

Bongaarts, J. (2001). Fertility and reproductive preferences in post-transitional societies. In R. A. Bulatao & J. B. Casterline (Eds.), Global fertility transition. Supplement to Population and Development Review, 27 (pp. 260–281). New York: Population Council.

Chesnais, J.-C. (2000). Determinants of below replacement fertility. Population Bulletin of the United Nations, 1999(40/41), 126–136.

De Graaf, A., & van Duin, C. (2007). Bevolkingsprognose 2006–2050: veronderstellingen over de geborte. Bevolkingstrends, 2007(1), 45–56.

Delgado, M., Meil, G., & Zamora López, F. (2008). Spain: Short on children and short on family policies. In: T. Frejka et al. (Eds.), Childbearing trends and policies in Europe. Demographic Research, Special collection 7, (Vol. 19(27), pp. 1059–1124).

Demeny, P. (2003). Population policy dilemmas in Europe at the dawn of the twenty-first century. Population and Development Review, 29(1), 1–28.

Engelhardt, H. (2004). Fertility intentions and preferences: Effects of structural and financial incentives and constraints in Austria. VID Working Papers 02/2004.

European Commission (2005). Confronting demographic change: A new solidarity between the generations. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities. [http://ec.europa.eu/employment_social/news/2005/mar/comm2005-94_en.pdf].

Fahey, T. (2007). Fertility patterns and aspirations among women in Europe. In J. Alber, T. Fahey, & C. Saraceno (Eds.), Handbook of quality of life in the enlarged European Union (pp. 27–46). London: Routledge.

Findl, P. (1989). Kinderwunsch nach demographischen Merkmalen. Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus Juni 1986. Statistische Nachrichten, 1989(10), 704–709.

Frejka, T., & Sobotka, T. (2008). Fertility in Europe: Diverse, delayed, and below replacement. In Frejka, T. et al. (Eds.), Childbearing Trends and Policies in Europe. Demographic Research, Special collection 7, (Vol. 19(3), pp. 15–46).

Goldstein, J., Lutz, W., & Testa, M. R. (2003). The emergence of sub-replacement family size ideals in Europe. Population Research and Policy Review, 22, 479–496.

Hagewen, K. J., & Morgan, S. P. (2005). Intended and ideal family size in the United States, 1970–1998. Population and Development Review, 31(3), 507–527.

Hanika, A. (1999). Realisierte Kinderzahl und zusätzlicher Kinderwunsch. Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus Juni 1996. Statistische Nachrichten, 1999(5), 311–318.

Heiland, F., Prskawetz, A., & Sanderson, W. C. (2005). Do the more-educated prefer smaller families? Paper presented at the 2005 Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, March 31–April 2, 2005.

Institut für Demographie. (1980). Kinderwünsche junger Österreicherinnen. [Child desires of young Austrian women]. Schriftenreihe, Heft 6, Institut für Demographie, Vienna, Austria.

Klapfer, K. (2003). Realisierte und ingesamt gewünschte Kinderzahl. Statistische Nachrichten, 2003(11), 824–832.

Kytir, J., Stefou, P., & Wiedenhofer-Galik, B. (2002). Familiale Strukturen und Familien-bildungsprognose. Mikrozensus 2001. Statistische Nachrichten, 2002(11), 824–840.

Liefbroer, A. C. (1999). From youth to adulthood: Understanding changing patterns of family formation from a life course perspective. In L. van Wissen & P. Dykstra (Eds.), Population issues. An interdisciplinary focus (pp. 53–86). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Liefbroer, A. C. (2008). Changes in family size intentions across young adulthood: A life-course perspective. European Journal of Population. doi:10.1007/s10680-008-9173-7

Lutz, W., Skirbekk, V., & Testa, M. R. (2006). The low fertility trap hypothesis. Forces that may lead to further postponement and fewer births in Europe. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 2006, 167–192.

Maxwald, R. (1994). Realisierte Kinderzahl und zusätzlicher Kinderwunsch nach demographischen Merkmalen. Statistische Nachrichten, 1994(7), 546–555.

McClelland, G. H. (1983). Family-size desires as measures of demand. In R. A. Bulatao & R. D. Lee (Eds.), Determinants of Fertility in Developing Countries, (Vol. 1, Chap. 9, pp. 288–343). New York: Academic Press.

McDonald, P. (2006). Low fertility and the state: The efficacy of policy. Population and Development Review, 32(3), 485–510.

Miettinen, A., & Paajanen, P. (2005). Yes, no, maybe: Fertility intentions and reasons behind them among childless Finnish men and women. Yearbook of Population Research in Finland, 41(2005), 165–184.

Morgan, S. P. (1981). Intention and uncertainty at later stages of childbearing: The United States 1965 and 1970. Demography, 18(3), 267–285.

Morgan, S. P. (1982). Parity-specific intentions and uncertainty: The United States, 1970 to 1976. Demography, 19(3), 315–334.

Morgan, S. P. (2001). Should fertility intentions inform fertility forecasts? In G. K. Spencer (Ed.), The direction of fertility in the United States. Proceedings of US Census Bureau Conference, Session III (pp. 153–170). Washington: US Census Bureau.

OECD. (2003). Babies and bosses. Reconciling work and family life (Vol. 2). Austria, Ireland and Japan: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris.

OECD. (2005). Education at a glance 2005. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Prskawetz, A., Sobotka, T., Buber, I., Gisser, R., & Engelhardt, H. (2008). Austria: persistent low fertility since the mid-1980s. In T. Frejka et al. (Eds.), Childbearing trends and policies in Europe. Demographic Research, Special collection 7, (Vol. 19(12), pp. 293–360).

Quesnel-Vallée, A., & Morgan, S. P. (2003). Missing the target? Correspondence of fertility intentions and behavior in the US. Population Research and Policy Review, 22(5–6), 497–525.

Régnier-Loilier, A. (2006). Influence of own sibship size on the number of children desired at various times of life. Population-E, 61(3), 165–194.

Régnier-Loilier, A., & Leridon, H. (2007). After forty years of contraceptive freedom, why so many unplanned pregnancies in France? Population & Societies, 439(September 2007), 1–4.

Rindfuss, R. R., Morgan, S. P., & Swicegood, G. (1988). First births in America. Changes in the timing of parenthood. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

Schoen, R., Astone, N. M., Kim, Y. J., & Nathanson, C. A. (1999). Do fertility intentions affect fertility behaviour? Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61(3), 790–799.

Smallwood, S., & Jefferies, J. (2003). Family building intentions in England and Wales: Trends, outcomes and interpretations. Population Trends, 112(Summer 2003), 15–25.

Sobotka, T., Šťastná, A., Zeman, K., Hamplová, D., & Kantorová, V. (2008). Czech Republic: A rapid transformation of fertility and family behaviour. In T. Frejka et al. (Eds.), Childbearing trends and policies in Europe. Demographic Research, Special collection 7, (Vol. 19(14), pp. 403–454).

Sobotka, T. & Testa, M. R. (2008). Attitudes and intentions towards childlessness in Europe. In Ch. Höhn, D. Avramov, & I. Kotowska (Eds.), People, population change and policies: lessons from the population policy acceptance study (Vol. 1, Chap. 9, pp. 177–211). Berlin: Springer.

Spéder, Z. & Kapitány, B. (2008). Realization of birth intentions: A focus on gender-related labor market effects and child-related benefits. Paper prepared within the FERTINT project.

Spielauer, M. (2005). Concentration of reproduction in Austria, General trends and differentials by education attainment and urban–rural setting. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 2005, 171–195.

Statistics Austria (1996). Volkszählung 1991. Haushalte und Familien. Series 1.030/26, Österreichisches Statistischen Zentralamt, Vienna.

Statistics Austria. (2005). Volkszählung 2001. Haushalte und Familien. Vienna: Statistics Austria.

Testa, M. R. (2006). Childbearing preferences and family issues in Europe. Special Eurobarometer 253/Wave 65.1 – TNS Opinion & Social, European Commission.

Testa, M. R. (2007). Childbearing preferences and family issues in Europe: Evidence from the Eurobarometer 2006 survey. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 2007, 357–379.

Thomson, E., & Hoem, J. M. (1998). Couple childbearing plans and births in Sweden. Demography, 35(3), 315–322.

Van Peer, C. (2002a). Desired and achieved fertility. In E. Klijzing & M. Corijn (Eds.), Dynamics of fertility and partnerships in Europe: Insights and lessons for comparative research (Vol. 2, pp. 117–142). New York and Geneva: United Nations.

Van Peer, C. (2002b). Kinderwens en realiteit: een analyse van FFs-gegevens met beschouwingen vanuit een macro-context. Bevolking en Gezin, 31(1), 79–123.

Van Peer, C., & Rabušic, L. (2008). Will we witness an upturn in European fertility in the near future? In Ch. Höhn, D. Avramov, & I. Kotowska (Eds.), People, population change and policies: Lessons from the population policy acceptance study (Vol. 1, Chap. 10, pp. 215–241). Berlin: Springer.

Voas, D. (2003). Conflicting preferences: A reason fertility tends to be too high or too low. Population and Development Review, 29(4), 627–646.

Westoff, C. F., & Ryder, N. B. (1977). The predictive validity of reproductive intentions. Demography, 14(4), 431–453.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Richard Gisser for supplying valuable information on Austrian Microcensus surveys, to Karin Schrittwieser from Statistics Austria for answering questions on the 2006 Microcensus survey, and to Werner Richter for carefully editing the manuscript. The article has greatly benefited from the comments and suggestions made by two anonymous reviewers as well as by Maria Rita Testa and Dimiter Philipov. The work was conducted within the project ‘Fertility Intentions and outcomes: The Role of Policies to Close the Gap’, funded by the European Commission, Directorate General for Employment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities (contract no. VS/2006/0685).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Questions on Fertility Intentions in Austrian Microcensus Surveys

Appendix: Questions on Fertility Intentions in Austrian Microcensus Surveys

1.1 German text

XK3 “Haben Sie den Wunsch, irgendwann in Ihrem weiteren Leben (noch) ein oder mehrere Kind(er) zu bekommen? Bitte rechnen Sie eine allfällige gegenwärtige Schwangerschaft mit!”:

[Responses: R01 “Ja”, R02 “Nein”, R03 “Weiß nicht”, (R04: no reply)]

XK4a “Wie viele Kinder wünschen Sie sich (noch)?”

[Responses: 1..15]

XK4b “Und wenn Sie gebeten werden, doch eine ungefähre Zahl anzugeben, wie viele Kinder wünschen Sie sich (noch)? Sie können auch eine Von-bis-Anzahl angeben.”

1.2 English translation:

XK3: “Do you desire to have (yet) a(nother) child at any point in your future life? Please include also current pregnancy”

Possible responses:

-

Yes (→ XK4a)

-

No (→ END)

-

Does not know (→ XK4b)

-

No answer, refusal (only in 1986–2001 waves, → END)

XK4a: “How many more children do you desire?”

Possible responses:

-

Number (1–15)

-

Does not know (only in 1986–2001 waves, → XK4b)

-

No answer, refusal (only in 1986–2001 waves, → END)

XK4b: “And when you were asked to provide an approximate number, how many children do you desire (yet)? You can also choose a range from—to”

Possible responses:

-

Number ‹from x to x›, excludes possibility of choosing no additional children

-

Does not know

-

No answer, refusal (only in 1986–2001)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sobotka, T. Sub-Replacement Fertility Intentions in Austria. Eur J Population 25, 387–412 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-009-9183-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-009-9183-0