Abstract

It is generally agreed upon that Grice’s causal theory of perception describes a necessary condition for perception. It does not describe sufficient conditions, however, since there are entities in causal chains that we do not perceive and not all causal chains yield perceptions. One strategy for overcoming these problems is that of strengthening the notion of causality (as done by David Lewis). Another is that of specifying the criteria according to which perceptual experiences should match the way the world is (Frank Jackson and Michael Tye). Finally, one can also try to provide sufficient conditions by elaborating on the content of perceptual experiences (Alva Nöe). These different strategies are considered in this paper, with the conclusion that none of them is successful. However, a careful examination of their problems points towards the general solution that we outline at the end.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We thank our anonymous reviewer for emphasizing that what constitutes a causal theory of perception is not uncontroversial as well as for the suggestion that the kinds of efforts we see as forming elaborations to the causal theory of perception might also be thought of in terms of causal representationalism.

It should be noted here that, although such empirical research supports our arguments, justification is purely philosophical. This is a crucial point as it has important methodological entailments: We think that our theory is accessible by ordinary vocabulary. More precisely, our reliance on neurological deficiencies is similar to the use of stories of obstructed perception or deviant causal paths in that they too might well be imaginary examples. Furthermore, these cases of deficiencies are useful in that they exemplify normal perception with one or another aspect missing. This is significant because it presents a better understanding of perception as no manipulation is involved and we also refrain from reference to perception in other kinds of beings, as is often the case in discussions of the causal theory of perception. Despite the use of such illustrations, then, our argument proceeds strictly along a philosophical route.

To be precise, Lewis speaks about scenes not objects. For present purposes this difference has little significance, however, although in general Lewis’s choice would force him to also develop an account of how we perceive objects in scenes.

In addition, if the perceived entity must be similar only qua properties of shape and size, then many situations where we use the term ‘perception’ would be excluded. That is, not all things we often claim to perceive have size and shape. Illumination, for example, which we sometimes perceive, has neither size nor shape (even though a lamp does).

In addition to the above-mentioned problems, this solution is also faced with a common but rarely discussed problem for theories of perception that rely on spatial properties: unlike in visual perception, spatial properties can more easily be absent in other perceptual modes. We can have, say, an auditory experience without awareness of where the source of the sound is located. Accordingly, insofar as we stick with spatial properties in strengthening the causal theory of perception, the prospects of extending it beyond visual perception are slim.

A similar course has been suggested by John Hyman (1994). We discuss Noë’s argumentation here as he explicitly situates his theory within the same tradition as Lewis, Jackson and Tye, as a broadened causal theory of perception (causal representationalism), whereas Hyman does not. In this way an elaboration of Noë’s theory provides a better starting point for the general theory of causal representationalism presented in the next section.

If the previous case is “hard to imagine”, let us consider it differently: if the neurosurgeon causes experiences in which the subject appears to move in relation to the perceived object and the subject is simultaneously moved in a way that corresponds with the experience, perspectival content would be veridical over time also. Interestingly, even though this might be difficult to imagine, the possibility appears to be theoretically feasible: Sony has already been granted numerous U.S. patents concerning a technology that it intends to use for producing such experiences. Needless to say, it would not save Noë’s theory if someone were to claim that the movement should be self-imposed since that would imply that we could not perceive things through train windows, for instance.

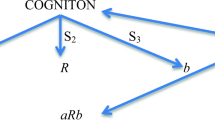

Agreeing with our previous discussion, our perception sometimes concerns objects, sometimes some particular properties of objects. Thus, the causal entities in question are objects, events, properties of objects, etc. Our perception simply is not restricted to any property or entity in all cases. Instead, the criteria for what is perceived come partly from our intentional relationship to what we perceive. Thus, there is a difference between perceiving “a ball”, “a red ball” or “a red ball over there”.

One should note that this does not require that we should be able to make a cognitive judgment concerning the object of perception. Quite the opposite: We do not want to claim that only conscious perception is possible or that our beliefs about the objects of our perception should play a role in constituting cases of perception. Rather, what is meant is that in general our perceptual experiences are about something.

Noë’s mistake lies, then, in seeing the difference between the neurosurgeon and the angel only in their ability to manipulate perception. Although having clearly set the conditions (noting that the angel provides “divine prosthetic vision” for instance), he fails to sufficiently allow for the angel’s inability to do anything but properly represent, while at the same time through this sleight-of-hand leaves untouched our strong intuition concerning the neurosurgeon’s voluntary choices and agency. In his own discussion, Noë dismisses the question of agency quickly having decided to concentrate on the issue of perspectival content (2003, pp. 98–99).

It might be worthwhile further clarifying the differentiating issues between the cases of the neurosurgeon, the angel and parent. This relates to the real capacity to influence the content of experiences in the sense of how objects in the world are experienced. The parent can only choose what it is that the child perceives but not how it is perceived. This separates it from the other two cases. What separates the neurosurgeon and angel from each other is in their freedom to manipulate the subject’s experiences. While both have the ability to cause us experiences to their liking, the angel cannot as it is tied to causing us experiences that match the world (i.e. it does not have real capacity to decide content). Hence, only neurosurgeon has the ability and freedom to cause us unveridical experiences. This is what separates it from the other two cases that we consider to be perception.

References

Bach-y-Rita, P. (1972). Brain mechanisms in sensory substitution. New York: Academic Press.

Grice, H. P. (1961). The causal theory of perception. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society (Suppl. Vol. 35), 121–152.

Hyman, J. (1994). Vision and power. The Journal of Philosophy, 91(5), 236–252. doi:10.2307/2940752.

Jackson, F. (1977). Perception. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, D. (1980). Veridical hallucination and prosthetic vision. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 58(3), 239–249. doi:10.1080/00048408012341251.

Millikan, R. G. (1984). Language, thought and other biological categories. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Bradford Books, MIT Press.

Noë, A. (2002). On what we see. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 83, 57–80. doi:10.1111/1468-0114.t01-1-00140.

Noë, A. (2003). Causation and perception: The puzzle unravelled. Analysis, 63(2), 93–100. doi:10.1111/1467-8284.00017.

Noë, A. (2004). Action in perception. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Bradford Books, MIT Press.

Poirier, C., Volder, A. D., Tranduy, D., & Scheiber, C. (2007). Pattern recognition using a device substituting audition for vision in blindfolded sighted subjects. Neuropsychologia, 45, 1108–1121. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.09.018.

River, Y., Hur, T. B., & Steiner, I. (1998). Reversal of vision metamorphosia. Archives of Neurology, 55, 1362–1368. doi:10.1001/archneur.55.10.1362.

Rizzo, M., & Vecera, S. P. (2002). Psychoanatomical substrates of Bálint’s syndrome. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 72, 162–178. doi:10.1136/jnnp.72.2.162.

Strawson, P. F. (1974). Causation in perception. In Freedom and resentment—and other essays (pp. 66–84). London: Methuen & Co Ltd.

Tye, M. (1982). A causal analysis of seeing. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 42, 311–325. doi:10.2307/2107488.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the two anonymous referees for their valuable comments, especially concerning our earlier version of the third condition for the theory of perception, which has undergone significant revisions. V. A. wishes to thank the Academy of Finland for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arstila, V., Pihlainen, K. The Causal Theory of Perception Revisited. Erkenn 70, 397–417 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-008-9153-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-008-9153-7