Abstract

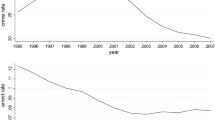

The need to provide justice at reasonable cost represents a current challenge for many public authorities. Many reform projects propose to remove some courts in order to rationalize the judiciary. This paper explores the 2008 French reform of labor courts (removing 20 % of the courts) to empirically investigate the determinants of the removal decision, and its consequences on demand for litigation and case duration in the remaining courts. This represents—to our knowledge—the first attempt to evaluate the impacts of courts’ removal. Using panel data, our empirical strategy is based on probit estimations, counterfactuals, as well as 3SLS estimations. Our results show that the reform removed small and concentrated courts. It decreased demand for litigation in the targeted areas. Results also suggest that case duration might have increased in some specific courts since 2011.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In 2013, France was convicted 66 times for judicial dysfunctions, including 51 cases relative to denial of justice in labor courts, caused by excessive delays (Lacabarats 2014). However, concerns about excessive delays are not specific to France. The European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ), created by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe in September 2002, was primarily set up to propose concrete solutions to current problems face by judiciaries, notably to reduce congestion in the European Court of Human Rights (CEPEJ 2014b).

Appeals are brought before the Cour d’Appel (Chambre sociale), and appeals against decisions of the cour d’appel are lodged in the Cour de cassation (Chambre sociale).

According to the French Ministry of Justice, 8 out of 10 cases in labor courts come from fired workers challenging their dismissals. Other cases are mainly about unpaid wages or unpaid compensations (De Maillard Taillefer and Timbart 2009).

Statistics come from both the Ministry of Justice (www.justice.gouv.fr/statistiques.html) and a report ordered by the Minister of Justice in 2014 (Lacabarats 2014).

The last general reform regarding the number of courts in France dated back to 1958. Another smaller reform targeting only labor courts was implemented in 1992: 11 labor courts were removed.

These figures come from the institution in charge of evaluating the public organizations and public services in France (Cour des Comptes). They are relative to the whole reform. Let us recall that this reform concerned not only labor courts but also civil and commercial courts. A total of 341 courts were removed, among which 62 were labor courts.

Départements are French administrative subdivisions of the territory. Metropolitan France is made up of 95 Départements.

Judges of removed labor courts were reallocated to other courts. Some 114 civil servants were working in removed labor courts: most of them have been reallocated to other jurisdictions, and 26 positions have been removed between 2008 and 2010 (Sénat 2012).

The exact criterion was to keep one labor court per département, and one on the geographical area of each civil court. These two geographical areas are more or less the same.

Illustrations of those fears were expressed in many newspapers, as in Le Monde, http://www.lemonde.fr/societe/article/2012/07/13/la-reforme-de-la-carte-judiciaire-une-occasion-manquee-selon-la-commission-des-lois-du-senat_1733397_3224.html (Last Access: January 2015).

Source: http://rue89.nouvelobs.com/2008/08/07/reforme-de-la-carte-judiciaire-dati-a-bien-dote-ses-amis (Last Access: January 2015).

The distance is calculated with Google Maps, and corresponds to the number of kilometers litigants have to drive from their current court to the closest court.

We take this rate at the Zone d’emploi (ZE) level. ZE are small subdivisions of the French territory used by the INSEE (the French Institute for Statistics). There are several ZE per département. We choose the unemployment rate at the ZE level because each labor court has a geographical competency in a given area that is close from the ZE.

We take it at the Département’s level. This information was available for 2005 only.

We take data from the 2009 census at the Département’s level.

Data from the French National Assembly.

Because of data availability, we exclude oversea regions from our analysis.

Région is another French administrative subdivision. Metropolitan France is currently made up of 22 régions. GDP is not available at the département level so that we use the regional level.

In other words, litigants cannot choose the court to which they bring their cases. Litigants affected to a removed court are re-affected to a new court and are obliged to bring their claims to this specific designated court. This new reallocation was enacted by Decree nº 2008-514 published on May 29th 2008 in the Official Journal of the French Republic. The Decree states that all cases are transferred as they stand and do not have to be reopened from the beginning.

The p value is associated with the two-group mean comparison test for 2009.

Note that data for the duration of cases terminated in 2008 are not available for the removed courts.

Note that the we do not observe such trends in other jurisdictions. Concerning the commercial courts, delays in 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2012 were 7.9, 7.4, 7.8, and 8.1 months on average at the national level. As far as civil courts are concerned, these delays were respectively 5.6, 5.9, 5.9 and 4.9 months. (These statistics come from the Ministry of Justice: www.justice.gouv.fr/statistiques.html).

Lay judges at the French labor courts are elected by both employees and employers. There is an equal number of judges elected by employers and by employees. Lists are proposed by both employers’ federations and employees’ unions. Most of the time, there is a common list from the employers’ federations, while employees’ unions compete. We control for the proportion of judges (at court level) elected by employees who are members of the two non-reformist unions, i.e. the two most leftist unions (CGT, FO) considered as the most demanding and “pro-employee” unions. The three other main unions are considered as “reformist”, i.e. more willing to negotiate with employers’ federations.

We choose 2007 rather than 2008 to make our counterfactual analysis, because the graph in the previous section showed a decrease in the number of new claims brought to the removed courts in 2008. It might be that litigants started anticipating the reform in 2008, and this impacted the decision to open new claims. We therefore consider cases in 2007 as the benchmark.

Our specifications do not include relativeBurden separately, since it already contains court fixed effects and relativeBurden is time-invariant. Including relativeBurden would generate collinear explanatory variables.

Let us recall that départage is a special procedure, in which lay judges ask a professional judge to intervene to help them to make a decision. Several reasons can justify départage (the need to clarify a legal argument, disagreement between lay judges about a decision or about the amount of damages\(\ldots\)). Lay judges can ask such an intervention but do not need to motivate the precise reason. This procedure increases duration: while claims without départage are terminated on average in 15 months, the duration increases up to 25 months when départage is required (De Maillard Taillefer and Timbart 2009).

The win rate for plaintiffs is about 3 to 1 with or without départage (Desrieux and Espinosa 2015).

We also run our estimations with the lagged value of WinRate, and results were qualitatively similar. We display the results for the contemporaneous values of WinRate to maximize the number of used observations.

Estimation of a system of related questions could also be obtained through 2SLS, or Full Information Maximum Likelihood techniques. Note however that the 3SLS technique is more efficient than the 2SLS estimation in presence of heteroscedasticity. The FIML estimation is as efficient as the 3SLS method if disturbances are normally distributed. We prefer to use the 3SLS estimation since the FIML makes an additional assumption.

One could think that the reform has also a conditional impact according to the changes of GDP per capita. However, the local GDP could also be impacted by the reform that changes the conditions on the labour market (by making dismissal more difficult to challenge). In this regard, our estimation must be seen as capturing an overall effect of the reform: it estimates both the direct reform’s effect (i.e. the decrease in the demand for litigation resulting from the increased costs in access to justice) and the indirect effects of the reform (i.e. changes in the number of new cases resulting from the new conditions in the labor market). However, as a robustness check, we have investigated whether the reform has had a conditional impact according to the level of GDP of the labor court’s region in 2008. We found no evidence suggesting that richer regions have been affected in a different way by the reform.

The variable \(distance_i\) has two special features. First, it is equal to zero for unaffected courts. This coding is arbitrary, but does not affect our results since \(distance_i\) is never used as a single regressor, but is always used in an interaction term which would yield to zero scores to unaffected courts. For more details, see Appendix 3. Second, \(distance_i\) is equal to the weighted average distance if the receiving courts take on the geographical competence of two removed courts. We take the average number of new cases between 2004 and 2007 for the weight of the removed courts.

Here, ‘on average’ refers to the average relative burden receiving courts have received (weighted by their average number of new cases between 2004 and 2007).

See Appendix 4 for the computation of the national average effects.

The demand for litigation at the national average is statistically different from the full report at the 99 % confidence level. The associated test yields a z-value equal to \(-3.94\).

Some references support this interpretation. For instance, the French INSEE website documents that richer regions attract more people (http://www.insee.fr/fr/ffc/ipweb/ip1501/ip1501). In addition, Marinescu shows that the number of dismissals that are challenged in France is positively correlated with economic growth: any additional point of economic growth leads to 0.59 point increase in new labor cases (Marinescu 2005, p.121).

Source: Official Report from the French Ministry of Economic and Financial Affairs entitled Note du Trésor, nº 137, October 2014.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Johnson, S. (2005). Unbundling Institutions. Journal of Political Economy, 113(5), 949–995.

Beenstock, M., & Haitovsky, Y. (2004). Does the appointment of judges increase the output of the judiciary? International Review of Law and Economics, 24(3), 351–369.

Botero, J. C., La Porta, R., López-de Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Volokh, A. (2003). Judicial reform. The World Bank Research Observer, 18(1), 61–88.

Botero, J. C., La Porta, R., & López-de Silanes, F. (2004). The regulation of labor. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(4), 1339–1382.

Boylan, R. T. (2004). Salaries, turnover, and performance in the federal criminal justice system. Journal of Law and Economics, 47(1), 75–92.

Buscaglia, E. (2001). Judicial corruption in developing countries: Its causes and economic consequences. Technical report, United Nations Office for Drug Control and Crime Prevention.

Buscaglia, E., Dakolias, M., & Ratliff, W. E. (1995). Judicial reform in Latin America. Stanford: Stanford University.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2005). Microeconometrics: Methods and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

CEPEJ. (2014a). Study on the functioning of Judicial Systems in the EU member states. Technical report.

CEPEJ. (2014b). Report on European judicial systems—Edition 2014 (2012 data): Efficiency and quality of justice. Technical report.

Chappe, N. (2012). Demand for civil trials and court congestion. European Journal of Law and Economics, 33(2), 343–357.

Chappe, N., & Obidzinski, M. (2014). The impact of the number of courts on the demand for trials. International Review of Law and Economics, 37, 121–125.

Chemin, M. (2009). The impact of the judiciary on entrepreneurship: Evaluation of Pakistan’s access to justice programme. Journal of Public Economics, 93(1–2), 114–125.

Chemin, M. (2012). Does court speed shape economic activity? Evidence from a court reform in India. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 28(3), 460–485.

Choi, S. J., Gulati, M., & Posner, E. (2009a). Are justices overpaid? A skeptical response to the judicial salary debate. Journal of Legal Analysis, 1(1), 47–117.

Choi, S. J., Gulati, M., & Posner, E. (2009b). Judicial evaluations and information forcing: Ranking state high courts and their judges. Duke Law Journal, 58, 1333–1381.

Choi, S. J., Gulati, M., & Posner, E. (2010). Professionals or politicians: The uncertain empirical case for an elected rather than appointed judiciary. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 26(2), 290–336.

Choi, S. J., Gulati, M., & Posner, E. (2011). How well do measures of judicial ability translate into performance? International Journal of Law and Economics, 33, 37–52.

Choi, S. J., Gulati, M., & Posner, E. (2012). What do federal district judges want? An analysis of publications, citations, and reversals. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 28(3), 518–549.

Cour des comptes. (2015). Rapport public annuel 2015. Technical report.

Cross, F. B., & Lindquist, S. (2009). Judging the judges. Duke Law Journal, 58, 1383–1437.

Dakolias, M. (1996). The judicial sector in latin america and the carribean elements of reform. World Bank Technical Paper, 319.

Dakolias, M. (1999). Court performance around the world: A comparative perspective. Yale Human Rights and Development Journal, 2(1), 87–142.

Dakolias, Maria, & Said, S. (1999). Judicial reform, a process of change through pilot courts. Legal and Judicial Reform Unit, Legal Department.

De Maillard Taillefer, L., & Timbart, O. (2009). Les affaires prud’homales en 2007. Technical report 105, Infostat, Ministère de la Justice.

Desrieux, C., & Espinosa, R. (2015). Do Employers fear unions in labor courts? theory and evidence from French labor courts. Working paper.

Deyneli, F. (2012). Analysis of relationship between efficiency of justice services and salaries of judges with two-stage DEA method. European Journal of Law and Economics, 34(3), 477–493.

Dimitrova-Grajzl, V., Grajzl, P., Sustersic, J., & Zajc, K. (2012a). Judicial incentives and performance at lower courts: Evidence from Slovenian judge-level data. Review of Law & Economics, 8(1), 215–252.

Dimitrova-Grajzl, V., Grajzl, P., Sustersic, J., & Zajc, K. (2012b). Court output, judicial staffing, and the demand for court services: Evidence from Slovenian courts of first instance. International Review of Law and Economics, 32(1), 19–29.

Djankov, S., La Porta, R., López-de Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2003). Courts. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(2), 453–517.

Doing Business. (2014). Doing business 2015: Going beyond efficiency. Technical report, the World Bank.

Eisenberg, T., Kalantry, S., & Robinson, N. (2013). Litigation as a measure of wellbeing. DePaul Law Review, 62, 247–292.

ENCJ. (2012). Judicial reform in Europe, 2011–2012. Technical report.

European Commission. (2014). The 2014 EU justice scoreboard. Technical report, European Commission.

Garoupa, N. (2014). Globalization and deregulation of legal services. International Review of Law and Economics, 38(S), 77–86.

Garoupa, N., Dalla Pellegrina, A., & Suardi, M. (2015). Do judges respond to monetary incentives? An empirical investigation. Working paper.

Gomes, C. (2007). The transformation of the portuguese Judicial Organization: Between efficiency and democracy. Utrecht law review.

Greene, W. H. (2003). Econometric Analysis (5th ed.). NJ: Upper saddle river.

IMF. (2014). Judicial system reform in Italy. Technical report, IMF working paper.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1998). Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy, 106(6), 1113–1115.

Lacabarats, A. (2014). L’avenir des juridictions du travail : Vers un tribunal prud’homal du \(XXI^{eme}\) siècle. Technical report, Rapport à Mme la Garde des Sceaux, Ministre de la Justice.

Lim, C. S. H. (2013). Preferences and incentives of appointed and elected public officials: Evidence from state trial court judges. The American Economic Review, 103(4), 1360–1397.

Mak, E. (2008). Balancing territoriality and functionality; specialization as a tool for reforming jurisdiction in the Netherlands, France and Germany. International Journal for Court Administration, 1(2), 2–9.

Marinescu, I. (2005). Coûts et procédures de licenciement, croissance et innovation technologique Coûts et procédures de licenciement, croissance et innovation technologique. PhD thesis, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales.

Marshall, D. (2013). Les juridictions du du \(XXI^{eme}\) siècle. Technical report, Rapport Mme la Garde des Sceaux, ministre de la Justice.

Maskin, E., & Tirole, J. (2004). The politician and the judge: Accountability in Government. American Economic Review, 94(4), 1034–1054.

Mitsopoulos, M., & Pelagidis, T. (2007). Does staffing affect the time to dispose cases in Greek courts? International Review of Law and Economics, 27, 219–244.

de Montesquieu, C. (1748). The spirit of laws.

OECD. (2013). Judicial performance and its determinants: A cross-country perspective. Technical report, OECD Economic Policy Papers.

Posner, R. A. (1998). Creating a legal framework for economic development. World Bank Research Observer, 13(1), 1–11.

Posner, R. A. (2000). Is the ninth circuit too large? A statistical study of judicial quality. The Journal of Legal Studies, 29(2), 711–719.

Larry, E. (1998). Ribstein. Ethical rules, agency costs and law firm structure. Virginia Law Review, 84, 1707–1759.

Sénat. (2012). La réforme de la carte judiciaire: Une occasion manquée. Technical report, Rapport d’Information de Mme Nicole Borvo Cohen-Seat et M. Yves Détraigne, fait au nom de la commission des lois.

Smith, A. (1762). Lectures on jurisprudence, Vol. 5. Glasgow Edition of Works.

Stephen, F. (2013). Lawyers, markets and regulation. London: Edward Elgar Publishers.

Stephen, F. H. (2002). The European single market and the regulation of the legal profession: An Economic analysis. Managerial and Decision Economics, 23(3), 115–125.

Van Djik, F., & Horatius, D. (2013). Judiciary in times of scarcity: Retrenchment and reform. International Journal for Court Administration, 5(1), 15–24.

Webber, D. (2007). Good budgeting, Better Justice: Modern budget practices for the judicial sector. Law and development working paper series, 3.

Jeffrey, M. (2002). Wooldridge. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

World Bank. (2011). Improving the performance of Justice Institutions. Technical report.

World Bank. (2012). The world bank: New directions in justice reform. Technical report.

Yoon, A. (2006). Pensions, politics, and judicial tenure: An empirical study of federal judges, 1869–2002. American Law and Economics Review, 8(1), 143–180.

Acknowledgments

This research was not funded by any institution. Data are publicly available on the websites of the Ministry of Justice and INSEE (French National Institute for Statistics). The authors are very thankful to the editor Alain Marciano for his great help and to three anonymous referees for useful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article was realized when H. Wan (student at ENSAE) made his internship at CRED research center.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Maps of judicial system

Appendix 2: Tables and figures

See Tables 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12.

Appendix 3: Marginal effects

General specification The general specification is given by the following equation system:

Note that these two equations do not include a control for relativeBurden only, because this would be collinear with the court fixed effects.

The marginal effects of the reform are:

Substituting each left-hand side in the right-hand side of the other equation:

which yields:

Time Specification The time specification include more interaction variables with the reform dummy. The time specification is defined by:

Note that these two equations do not include a control for numYears only because this would be collinear with the year fixed effects. Moreover, it does not include the term \(numYears_{t} \times relativeBurden_{i}\) because this would be collinear with \(r_{it} \times numYears_{t} \times relativeBurden_{i}\). Indeed, the number of years is equal to zero for all courts before 2009 (numYears). Moreover, the relative burden courts receive is equal to zero for all non-receiving courts (relativeBurden). Multiplying the interaction term by \(r_{it}\) would not affect the values of the new variable, which would create perfect collinearity.

The marginal effects of the reform are given by:

which yields:

Spatial Specification The spatial specification is defined by the following system of equations:

Note that these two equations do not include controls for distance nor \(relativeBurden \times distance\) because they would be collinear with the court fixed effects.

The marginal effects of the reform are given by:

which yields:

Appendix 4: Marginal effects at the national level

In order to compute the national average effect of the reform, we attribute a weight \(w_i\) to each court. Let us denote \(z_j\) the average number of claims between 2004 and 2007 the removed court j was dealing with. For each receiving court i, we denote J(i) the set of removed courts the receiving court i is taking on. Each weight is defined as:

It follows that \(\sum _i w_i = 1\).

General Specification Let us denote f(relativeBurden) the marginal impact of the reform conditionally on relativeBurden. In the general 3SLS specification, the average national effect of the reform on the dependent variable is linear in relativeBurden (see previous section in the appendix). The national average marginal impact corresponds to \(\sum _i w_i f(relativeBurden_i)\).

Moreover, because of the linearity of f(.), we have:

It follows that, because of the linearity of the marginal effect, the average marginal effect is equal to the marginal effect at the average. We can therefore compute the national average effect by considering the marginal effect at the national average.

Spatial Specification Let us denote g(relativeBurden, distance) the marginal impact of the reform conditionally on both the relativeBurden and the distance of a court. The previous section has shown that the marginal effect is a function of the form: \(g(x,y)=ax+by+cxy+d\). The national average marginal impact is defined by \(\sum _i w_i g(relativeBurden_i, distance_i)=\sum _i g_i\). Unlike in the general setting, the marginal impact is not linear anymore. The national marginal impact is given by:

The data yield the following results:

Time Specification The time specification conditions the impact of the reform on both the relative burden of the receiving courts and the number of years the reform has been enforced. Since each graph of Figs. 6 and 7 is already conditioned on the year, the marginal effect is linear, and results are similar to the general specification. We can take the marginal effect at the national average to estimate the national average marginal effect.

Appendix 5: Graphs of marginal effects

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Espinosa, R., Desrieux, C. & Wan, H. Fewer courts, less justice? Evidence from the 2008 French reform of labor courts. Eur J Law Econ 43, 195–237 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-015-9507-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-015-9507-y