Abstract

This paper looks at the decision to settle patent litigation in Germany by focusing on detailed data on within-trial actions and motivations by plaintiff, defendant and the courts. Using a new dataset covering about 80 % of all patent litigation cases in Germany between 2000 and 2008 we estimate the likelihood of within-trial settlement. We find that the within-trial settlement decision is to some degree driven by the proceedings that change the pre-trial setting of the negotiations in terms of information and stakes and make previously refused settlement a new option. Additionally, firm-specific stakes as measured by the relation of the involved parties to the disputed patent as well as firm-specific strategies are found to affect the general willingness to settle after the filing of a court case. The results suggest that pre-trial failure of settlement negotiations can to some extent be offset by within-trial settlement through efforts made by the court, but that the disposition to settle is to a larger degree determined by firm-specific stakes and strategies in the case.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Depending on the definition of settlement the number varies between 44 and 62 %. We will elaborate on this difference in the course of the paper.

The difference to Cremers is most likely due to the definition of a settlement event and the choice of courts considers as these differ with respect to settlement rates.

The remaining 20 % are cases spread over the nine remaining district courts responsible for patent litigation. As these courts are of minor importance and reputation, we chose to abstain from collecting data at those courts for cost reasons.

Cases with the defendant being the patent owner are not classical infringement suits, but either employer–employee disputes about patent ownership or counter suits asking for a declaration of non-infringement. As we cannot clearly distinguish between these cases we drop them from the analysis.

The variable takes the value one when either the court records of the Federal Patent Court (responsible for invalidity actions) or the infringement court record reveals that an invalidity suit has been filed during trial. We thank Fabian Gässler for providing us with the data from the Federal Patent court.

Lanjouw and Schankerman (2004).

We do not constrain the citations to the date of litigation as we use this measure for both the litigated patents and a control group of non-litigated patents used in the robustness checks.

This correction is done using the table "docdb family" in PATSTAT.

We use the "docstd name" of the patentee to identify self-citations.

This type of model is well explained e.g. in Dubin and Rivers (1989).

The coverage of all four digit IPC classes contained in the litigation data has been verified.

In an appeal case court costs increase about 15 % and appeals at the Federal Supreme court are twice as high as the first instance proceedings (Bardehle and Pagenberg 2010, p. 13).

References

Allison, J. R., Lemley, M. A., & Walker, J. (2011). Patent quality and settlement among repeat patent litigants. Georgetown Law Journal, 99, 677.

Bardehle & Pagenberg (2010), Patent Infringement Proceedings. Retrieved August 28, 2013 from http://www.bardehle.com/en/publications/search_in_all_publications.html.

Bebchuk, L. A. (1984). Litigation and settlement under imperfect information. RAND Journal of Economics, 15(3), 404–415.

Bernheim, B. D., & Whinston, M. D. (1990). Multimarket contact and collusive behavior. The RAND Journal of Economics, 21(1), 1–26.

Bessen, J., & Meurer, M. J. (2006). Patent litigation with endogenous disputes. AEA Papers and Proceedings 96(2).

Bessen, J., & Meurer, M. J. (2007). What’s wrong with the patent system? Fuzzy boundaries and the patent tax. First Monday, 12(6). doi:10.5210/fm.v12i6.1867.

Cooter, R. D., & Rubinfeld, D. L. (1989). Economic analysis of legal disputes and their resolution. Journal of Economic Literature, 27(3), 1067–1097.

Cremers, K. (2007). Incidence, settlement and resolution of patent litigation suits in Germany, PhD thesis, University of Mannheim. p. 121 http://madoc.bib.uni-mannheim.de/madoc/volltexte/2007/1405/.

Cremers, K. (2009). Settlement during patent litigation trials. Empirical analysis for Germany. Journal of Technology Transfer, 34(2), 182–195.

Cremers, K., Ernicke, M., Gaessler, F., Harhoff, D., Helmers, C., Mc Donagh, L., Schliessler, P., & van Zeebroeck, N. (2013). Patent litigation in Europe, ZEW discussion paper no. 13-072, Mannheim.

Dubin, J. A., & Rivers, D. (1989). Selection bias in linear regression, logit and probit models. Sociological Methods and Research, 18, 361–391.

Graham, S. J. H., & Harhoff, D. (2006). Can post-grant reviews improve patent system design? A twin study of US and European patents, discussion papers in economics 38, Free University of Berlin, Humboldt University of Berlin, University of Bonn, University of Mannheim, University of Munich.

Helmers, C., & McDonagh, L. (2013). Patent litigation in the UK: An empirical survey 2000–2008, August 2013, Mimeo.

Lanjouw, J. O., & Lerner, J. (1998). The enforcement of intellectual property rights: A survey of the empirical literature. Annales d’Économie et de Statistique Issue, 49(50), 223–246.

Lanjouw, J. O., & Schankerman, M. (2001). Characteristics of patent litigation: A window on competition. RAND Journal of Economics, 32(1), 129–151.

Lanjouw, J. O., & Schankerman, M. (2004). Protecting intellectual property rights: Are small firms handicapped? Journal of Law and Economics, 47(1), 45–74.

Lemley, M., & Shapiro, C. (2005). Probabilistic patents. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(2), 75–98.

Merges, R. P., & Nelson, R. R. (1990). On the complex economics of patent scope. Columbia Law Review, 90, 839.

Meurer, M. J. (1989). The settlement of patent litigation. RAND Journal of Economics, 20(1), 77–91.

Priest, G. L., & Klein, B. (1984). The selection of disputes for litigation. Journal of Legal Studies, 13(1), 1–55.

Shapiro, C. (2001). Navigating the patent thicket: Cross licenses, patent pools, and standard setting, NBER Chapters. In Innovation policy and the economy (Vol. 1, pp. 119–150). National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Shapiro, C. (2003). Antitrust limits to patent settlements. RAND Journal of Economics, 34(2), 391–411.

Somaya, D. (2003). Strategic determinants of decisions not to settle patent litigation. Strategic Management Journal, 24(1), 17–38.

Tirole, J. (1988). The theory of industrial organization. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Trajtenberg, M. (1990). A penny for your quotes: Patent citations and the value of innovations. RAND Journal of Economics, 21(1), 172–187.

Waldfogel, J. (1998). reconciling asymmetric information and divergent expectations theories of litigation. Journal of Law and Economics, 41(2), 451–476.

Weatherall, K. G., & Jensen, P. H. (2005). An empirical investigation into patent enforcement in Australian Courts. Federal Law Review, 32, 239.

Ziedonis, R. H. (2004). Don’t fence me in: Fragmented markets for technology and the patent acquisition strategies of firms. Management Science, 50(6), 804–820.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the funding of this research project by the Centre for European Economic Research (ZEW) within the Research program “Strengthening Efficiency and Competitiveness in the European Knowledge Economies” (SEEK) and by the Thyssen Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

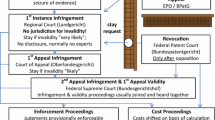

1.1 The patent litigation system in Germany: legal rules and procedures

For a granted patent a first possibility to be involved in a dispute is an opposition procedure right after the grant of the patent. This procedure takes place if a third party, usually a competitor, argues that the patent should not have been granted (Article 99 EPC, Paragraph 59 PatG). Opposition procedures take place at the DPMA or EPO opposition divisions. A granted patent, coming from a German Patent application or from a Germany-designated EPO application, becomes national law. The German system separated validity and infringement proceedings. While invalidity decisions are rendered by the German Patent Court, infringement are cases are dealt with by the district courts. In Germany there are twelve District courts qualified for dealing with patent infringement cases. The legal procedures are set in the Code for Civil Procedures (ZPO). Other than in most types of actions in patent infringement cases the involved parties are relatively free to choose the venue. The plaintiff can choose between either the jurisdiction of the defendant or the court in the jurisdiction where the potential infringement has taken place. Once suspecting an infringement and having obtained some evidence the patentee can send an official warning to the infringer (caution), asking him to stop infringing the patented invention and to provide a legally binding “cease and desist” declaration. If the defendant does not react, the plaintiff may file a suit. The defendant may however file a counterclaim asking for the declaration of non-infringement in order to have his position confirmed. In order to avoid such an action for a negative declaratory judgment, the patentee can chose to send an inquiry asking the other party about the legitimacy of their actions. In some urgent cases, a preliminary injunction is applied for when the suspected infringing party is about to start selling a product involving the disputed technology and when substantial losses for the patent owner may result. There will be a defense plea and then a reply to the defense plea, which may again be followed by a rejoinder. These proceeding then lead to an oral hearing before court and may be continued as written procedures or followed by further oral hearings until the publication of the final judgment. It is the responsibility of the parties to provide evidence in favor or against the case, and the court does not conduct any investigations on its own. If the three judges decide that they are unable to assess technical questions, they will appoint a technical expert, who submits a report and is present at the oral hearings. Both parties may then comment on the expert’s opinion. The appointment of an expert opinion usually delays the procedure by about 9–12 months. A common defense procedure of the defendant is to file invalidity procedure at the German Patent court. While in other countries invalidity issues are dealt with by the same court as infringement issues, the German bifurcation system separates these issues. A invalidity suit as such therefore does not directly interfere with the infringement suit. If however the district court does suspect an infringement of the patent, but at the same time suspects the patent to be judged invalid by the German Patent court, it will defer the infringement action until the invalidity case has been resolved. In the majority of cases however the decision regarding invalidity is rendered after the termination of the infringement proceedings. Patent infringement procedures can terminate with a judgment, a judgment by default, a within—court or out-of-court settlement or with a withdrawal of the case. The losing party is obliged to pay the attorney fees of the winning party, the court costs and any further expenses. The attorney and court fees are being calculated according to a formula based on the estimated value of the dispute.Footnote 14

1.2 21 industry codes derived from the 2-digit revision 2 NACE codes

- A:

-

Agriculture, forestry and fishing

- B:

-

Mining and quarrying

- C:

-

Manufacturing

- D:

-

Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply

- E:

-

Water supply, sewerage, waste management and remediation activities

- F:

-

Construction

- G:

-

Wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles

- H:

-

Transporting and storage

- I:

-

Accommodation and food service activities

- J:

-

Information and communication

- K:

-

Financial and insurance activities

- L:

-

Real estate activities

- M:

-

Professional, scientific and technical activities

- N:

-

Administrative and support service activities

- O:

-

Public administration and defense; compulsory social security

- P:

-

Education

- Q:

-

Human health and social work activities

- R:

-

Arts, entertainment and recreation

- S:

-

Other services activities

- T:

-

Activities of households as employers; undifferentiated goods and services

- U:

-

Activities of extraterritorial organization and bodies

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cremers, K., Schliessler, P. Patent litigation settlement in Germany: why parties settle during trial. Eur J Law Econ 40, 185–208 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-014-9472-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-014-9472-x