Abstract

The present paper attempts to bridge the gap between the cooperative and the non-cooperative approach employed to examine the size of stable coalitions, formed to address global environmental problems. We do so by endowing countries with foresightedness, that is, by endogenizing the reaction of the coalition’s members to a deviation by one member. We assume that when a country contemplates withdrawing or joining an agreement, it takes into account the reactions of other countries ignited by its own actions. We identify conditions under which there always exists a unique set of farsighted stable IEAs. The new farsighted IEAs can be much larger than those some of the previous models supported but are not always Pareto efficient.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Diamantoudi and Sartzetakis (2006) show that in the model adopted by Barrett (1994) the equilibrium size of an IEA is either 2, 3 or 4 countries. Similarly, Finus and Rundshagen (2001) show that in the model adopted by Carraro and Siniscalco (1993) when transfers are not allowed the equilibrium size of an IEA is 2 or 3 countries.

It is clear, especially from the experience with the Kyoto Protocol, that signing does not necessarily imply ratification of an IEA. Although, following the literature we mostly use the term signing (signatory country), our analysis bears on the ratification of an IEA.

Diamantoudi and Sartzetakis (2015) show that using general functional forms the size of the coalition could be significant, but even in such cases the level of welfare does not improve relative to the laissez-faire state where each country optimizes individually.

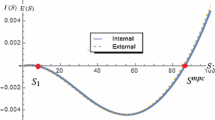

The point of intersection between \(\omega _{s}(s)\) and \(\omega _{ns}(s)\) when s is a real number has been identified independently by Rutz and Borek (2000), but the authors did neither identify the relation between the two functions beyond the point of intersection, nor the fact that the point of intersection is the lowest point of \(\omega _{s}(s)\).

A dominance relation is a binary relation that allows us to compare any two elements (in our case IEAs) and select the stable ones. A myopic dominance relation embeds not only the preference by the acting agent but also the ability for that agent to induce the dominant element from the dominated one. A farsighted dominance relation captures a sequence of elements whereas each acting agent prefers the ultimate outcome (end of the sequence) to his status quo, while he can only induce the next step of the sequence.

Diamantoudi and Xue (2007) have applied previously vN–M’s stable sets as an equilibrium concept.

This feature of the stable set is known as Internal Stability, yet we will avoid the terminology since it coincides with the one attributed to coalitions which is entirely different. Characterizing a coalition as internally stable implies that no member wishes to exit the coalition. This latter meaning of internal stability is the one we will maintain throughout the paper as formalized in Definition 1 that follows.

This feature of the stable set is known as External Stability. The same problem with terminology arises here as well. We will maintain the meaning of external stability as formalized in Definition 1.

Its appeal is captured and improved upon by Greenberg (1990). In the Theory of Social Situations (TOSS), a unifying approach towards cooperative and non-cooperative game theory, where any behavioral and institutional assumptions are explicitly defined, an equivalence is shown between the von Neumann and Morgenstern (vN–M) stable set and the Optimistic Stable Standard of Behavior (OSSB), a solution concept built in the spirit of vN–M stability, yet with the precise assumption of optimistic behavior explicitly formalized. TOSS amplified the pertinence of stability by recasting the dominance relation into a broader concept beyond the boundaries of a binary relation. In doing so, behavioral assumptions can be imposed on the agents, and more complex institutional settings can be analyzed.

Note that through considering decreasing and increasing sequences of coalitions (through internal and external stability) we exhaust all possibilities. Allowing for simultaneous entry and exit does not add to our analysis given that countries are symmetric. Although other definitions of stability could be used, we have chosen the one defined in D’ Aspremont et al. (1983), in order to allow for direct comparison with the myopic literature’s results.

Diamantoudi (2005) within the context of cartel stability in a price leadership model establishes that such a dominance relation is acyclic if the coalition members’ payoff is inreasing in the size of the coalition, that is, in our context, when \(\omega (s)\) is increasing in s.

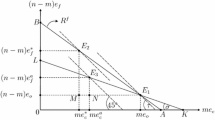

The solution of the problem is presented in Diamantoudi and Sartzetakis (2006).

References

Barrett S (1994) Self-enforcing international environmental agreements. Oxf Econ Pap 46:878–894

Barrett S (2003) Environment & statecraft: the strategy of environmental treaty-making. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Botteon M, Carraro C (2001) Environmental coalitions with heterogeneous countries: burden-sharing and carbon leakage. In: Ulph A (ed) Environmental policy, international agreements, and international trade. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Carraro C (2003) International environmental negotiations. In: Wiener J, Schriner R (eds) International relations, encyclopedia of life support systems, developed under the auspices of UNESCO. EOLSS Publishers, Oxford, pp 93–113

Carraro C, Siniscalco D (1993) Strategies for the international protection of the environment. J Pub Econ 52:309–328

Carraro C, Moriconi F (1998) International games on climate change control. FEEM working paper, 56.98

Chander P (2007) The gamma-core and coalition formation. Int J Game Theory 35:539–556

Chander P, Tulkens H (1992) Theoretical foundations of negotiations and cost-sharing in transfrontier pollution problems. Eur Econ Rev 36:388–398

Chander P, Tulkens H (1997) The core of an economy with multilateral environmental externalities. Int J Game Theory 26:379–401

Chwe MS-Y (1994) Farsighted coalitional stability. J Econ Theory 63:299–325

D’Aspremont CA, Jacquemin J, Gabszewicz J, Weymark JA (1983) On the stability of collusive price leadership. Can J Econ 16:17–25

de Zeeuw A (2008) Dynamic effects on the stability of international environmental agreements. J Environ Econ Manag 55:163–174

Diamantoudi E (2005) Stable cartels revisited. Econ Theory 26:907–921

Diamantoudi E, Xue L (2007) Coalitions, agreements and efficiency. J Econ Theory 136:105–125

Diamantoudi E, Sartzetakis E (2006) Stable international environmental agreements: an analytical approach. J Pub Econ Theory 8:247–263

Diamantoudi E, Sartzetakis E (2015) International environmental agreements: coordinated action under foresight. Econ Theory 59:527–546

Ecchia G, Mariotti M (1998) Coalition formation in international environmental agreements and the role of institutions. Eur Econ Rev 42:573–582

Eyckmans J (2001) On the farsighted stability of the kyoto protocol. Working Paper Series, Faculty of Economics and Applied Economic Sciences, University of Leuven, No. 2001-03

Finus M, Ierland Van E, Dellink R (2006) Stability of climate coalitions in a cartel formation game. Econ Gov 7:271–291

Finus M (2003) Stability and design of international environmental agreements: the case of transboundary pollution. In: Folmer H, Tietetenberg T (eds) The international yearbook of environmental and resource economics 2003–2004. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 82–158

Finus M, Rundshagen B (2001) Endogenous coalition formation in global pollution control. FEEM, working paper, 43.2001

Fuentes-Albero C, Rubio SJ (2010) Can international environmental cooperation be bought? Eur J Oper Res 202:255–264

Greenberg J (1990) The theory of social situations: an alternative game-theoretic approach. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Harsanyi JC (1974) Interpretation of stable sets and a proposed alternative definition. Manag Sci 20:1472–1495

Ioannidis A, Papandreou A, Sartzetakis E (2000) International environmental agreements: a literature review. GREEN working paper, Universite Laval 00-08

Kolstad CD (2010) Equity, heterogeneity and international environmental agreements. B.E. J Econ Anal Policy 10(2), 1–17

Mariotti M (1997) A model of agreements in strategic form games. J Econ Theory 74:196–217

McGinty M (2007) International environmental agreements among asymmetric nations. Oxf Econ Pap 59:45–62

Ray D, Vohra R (1997) Equilibrium binding agreements. J Econ Theory 73:30–78

Ray D, Vohra R (1999) A theory of endogenous coalition structures. Games Econ Behav 26:286–336

Ray D, Vohra R (2001) Coalitional power and public goods. J Polit Econ 109:1355–1384

Rubio JS, Ulph U (2006) Self-enforcing international environmental agreements revisited. Oxf Econ Pap 58:223–263

Rutz S, Borek T (2000) International environmental negotiations: does coalition size matter? WIF ETH working paper 00/20

Tulkens H (1998) Cooperation versus free-riding in international environmental affairs: two approaches. In: Hanley Nick, Folmer Henk (eds) Game theory and the environment. E. Elgar, Cheltenham

von Neumann J, Morgenstern O (1944) Theory of games and economic behavior. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Xue L (1998) Coalitional stability under perfect foresight. Econ Theory 11:603–627

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The authors are indebted to the Journal’s Co-Editor prof. M. Finus and two referees for their insightful comments that greatly improved the exposition of the results. Sartzetakis gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Research Funding Program: “Thalis—Athens University of Economics and Business—Optimal Management of Dynamical Systems of the Economy and the Environment: The Use of Complex Adaptive Systems” cofinanced by the European Union (European Social Fund—ESF) and Greek national funds.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Diamantoudi, E., Sartzetakis, E.S. International Environmental Agreements—The Role of Foresight. Environ Resource Econ 71, 241–257 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-017-0148-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-017-0148-1