Abstract

This paper analyzes private incentives for precautions against environmental harm before accidents occur and for clean-up after the fact. We consider the compensatory regimes used in various jurisdictions, which differ in terms of the basis for compensation (the level of harm, clean-up costs, or some combination of the two) and the resulting levels of compensation. We establish that socially optimal decisions are usually not induced by liability law in any of the compensatory regimes. However, the different types and levels of compensation have distinct effects, allowing the policy maker to identify the most appropriate regime for specific circumstances.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Among the tools used to perform ecosystem service valuation are revealed preference methods using observations of economic behavior, stated preference methods using information generated by surveys (e.g. applying the contingent valuation method) as well as cost-based evaluation using information about avoided damages as well as replacement cost. See Kennedy and Cheong (2013) and National Research Council (2011) for a discussion of conceptional issues and applications to the off-shore Deepwater Horizon oil spill catastrophe. The types of ecosystem services losses due to the catastrophe considered in the aforementioned studies are supporting services (like soil-and-sediment balance and nutrient balance), regulating services (like water quality and climate balance), provisioning services (like food and medical resources) as well as cultural services (like recreational opportunities as well as science and education).

This is not to say that other repercussions have been neglected in the literature. For example, Endres and Friehe (2011) establish that deviations between the level of harm and the level of compensation distort tortfeasors’ incentives to invest in technical progress.

See the seminal paper by Tietenberg (1989) and the more recent discussion in Endres (2011). However, neither of these two contributions addresses the questions raised by different understandings of compensation in terms of type and level, the issue at the core of the present paper. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this paper is the first to deal with this topic.

The authors gratefully acknowledge that the following examples were provided by Eckard Rehbinder, Professor emeritus of Law, Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany. Special thanks also go to Martin Nettesheim, Professor of Law, University of Tübingen, Germany.

In line with most of the literature on the economics of liability law, the level of \(D\) is taken to be deterministic in the following analysis. The analysis of a scenario in which the level of harm is \(D(x,y,\theta )\) where \(\theta \in [\underline{\theta },\bar{\theta }]\) is a random variable according to the cumulative distribution function \(F(\theta )\), and \((x,y)\) are chosen in view of the distribution of \(\theta \) and \(s\) is chosen contingent upon the realized value of \(\theta \) would be qualitatively comparable.

In our extensions, we briefly refer to the case in which victims can also influence the probability of environmental harm.

For further elaboration, see Calcott and Hutton (2006) and Endres and Friehe (2012), for example. We make this assumption because it has already been established that strict liability cannot induce optimal decisions in the case of multi-causality. The two seminal sources for these fundamental insights in the field of law and economics are Landes and Posner (1980), p. 523, and Shavell (1987), Proposition 7.1, p. 178.

These gases have greater density than air. Therefore, they only disperse close to the origins of their emissions.

In earlier literature, CO2 was not considered to be a pollutant that generated “damage”. However, this view has evolved considerably in more recent discussions. See, for example, Greenstone et al. (2013).

In actual legislation, whether strict liability or negligence applies commonly depends on the activity. For instance, the Environmental Liability Directive of the European Union (Directive 2004/35/CE of the European Parliament and of the Council, Official Journal of the European Union L 143, 30.04.2004, 56–77) lists specific activities that are subject to strict liability.

We similarly do not address victims’ incentives to overstate the harm suffered. Such incentives are addressed, for example, in Friehe (2009b).

The scenario in which potential injurers and potential victims choose the precaution level at the same time is standard in the literature on the economics of liability (e.g., Shavell 2007). The consideration of leadership in care-taking is a possibly fruitful extension. Modeling this kind of strategic interaction would require that the injurer anticipates the safety effort of potential victims as a best response to his safety. This would introduce additional strategic aspects and thereby enrich (and considerably complicate) our analysis of the different regimes. Such aspects are discussed in Endres (1992) and Wittman (1981), for instance. However, they are beyond the scope of the present paper.

Note that we assume symmetric behavior by all \(n\) potential victims, an assumption that is validated in equilibrium.

Although the privately optimal level of clean-up is a function of the precautions exerted by the polluter and each victim (\(x\) and \(y\), respectively), this dependence is not evident in the conditions (15) and (17) below. This results from the fact that the injurer’s payoffs are independent of clean-up, as is apparent from (14), and because the victim adapts clean-up at stage 2 in a privately optimal way (which implies that there is no indirect cost effect).

The fact that \(C\le sD\) was explained in Sect. 2.

The level of \(s\) that figures in (25) is the same as that in (17) for a given combination \((x,y)\), because it is equal to \(s^*(x,y)\) in both cases. In other words, at a given combination \((x,y)\), differences in incentives cannot be attributed to different levels of anticipated clean-up. This simplifies the comparison of the regimes.

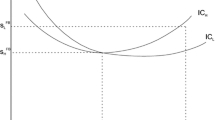

Note that RegimeCs induces \(s=1\), which is a distinction of this scheme relative to the other compensatory regimes; to simplify the exposition, this is not incorporated into the illustration.

References

Barrett J, Segerson K (1997) Prevention and treatment in environmental policy design. J Environ Econ Manag 33:196–213

Bennear LS, Stavins RN (2007) Second-best theory and the use of multiple policy instruments. Environ Resour Econ 37:111–129

Calcott P, Hutton F (2006) The choice of a liability regime when there is a regulatory gatekeeper. J Environ Econ Manag 51:153–164

Chang HF, Sigman H (2007) The effect of joint and several liability under superfund on brownfields. Int Rev Law Econ 27:363–384

Cooter R, Porat A (2001) Should courts deduct nonlegal sanctions from damages? J Legal Stud 30:401–422

Cooter R, Ulen T (2012) Law Econ, 6th edn. Prentice Hall, Boston

Endres A (1992) Strategic behavior under tort law. Int Rev Law Econ 12:377–380

Endres A (2011) Environmental economics—theory and policy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Endres A, Friehe T (2011) R&D and abatement under environmental liability law: comparing incentives under strict liability and negligence if compensation differs from harm. Energy Econ 33:419–425

Endres A, Friehe T (2012) Generalized progress of abatement technology: incentives under environmental liability law. Environ Resour Econ 53:61–71

Friehe T (2009a) Sequential torts and bilateral harm. Int Rev Law Econ 29:161–168

Friehe T (2009b) Screening accident victims. Int Rev Law Econ 29:272–280

Greenstone M, Kopits E, Wolverton A (2013) Developing a social cost of carbon for us regulatory analysis: a methodology and interpretation. Rev Environ Econ Policy 7:23–46

Innes R (1999) Self-policing and optimal law enforcement when violator remediation is valuable. J Polit Econ 107:1305–1325

Kennedy CJ, Cheong S (2013) Lost ecosystem services as a measure of oil spill damages: a conceptual analysis of the importance of baselines. J Environ Manag 128:43–51

Landes W, Posner R (1980) Joint and multiple tortfeasores: an economic analysis. J Legal Stud 9:517–556

Muller N, Mendelsohn R (2009) Efficient pollution regulation: getting the prices right. Am Econ Rev 99: 1714–1739

NRC (National Research Council) (2011) Approaches for ecosystem services valuation for the Gulf of Mexico after the deepwater horizon oil spill: interim report. Committee on the Effects of the Deepwater Horizon Mississippi Canyon-252 Oil Spill on Ecosystem Services in the Gulf of Mexico. Technical report, National Research Council, Washington, DC

Polinsky AM, Shavell S (1994) A note on optimal cleanup and liability after environmentally harmful discharges. Res Law Econ 16:17–24

Porat A, Tabbach A (2011) Willingness to pay, death, wealth, and damages. Am Law Econ Rev 13:45–102

Schäfer HB, Müller-Langer F (2009) Strict liability versus negligence. In: Faure M (ed) Tort law and economics, 2nd edn. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Segerson K (1993) Liability transfers: an economic assessment of buyer and lender liability. J Environ Econ Manag 25:46–63

Shavell S (1987) Economic analysis of accident law. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Shavell S (2004) Foundations of economic analysis of law. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Shavell S (2007) Liability for accidents. In: Polinsky AM, Shavell S (eds) Handbook of law and economics 1. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Sigman H (2010) Environmental liability and redevelopment of old industrial land. J Law Econ 53:289–306

Tietenberg TH (1989) Indivisible toxic torts: the economics of joint and several liability. Land Econ 65: 305–319

Visscher L (2009) Tort damages. In: Faure M (ed) Tort law and economics, 2nd edn. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Watts A (1998) Insolvency and the division of cleanup costs. Int Rev Law Econ 18:61–76

Weitzman ML (2009) Additive damages, fat-tailed climate dynamics, and uncertain discounting. Economics 3:2009–2039

Weitzman ML (2010) What is the damages-function for global warming and what difference might it make? Clim Chang Econ 1:57–69

Wittman D (1981) Optimal pricing of sequential inputs: last clear chance, mitigation of damages, and related doctrines in the law. J Legal Stud 10:65–91

Xepapadeas A (1997) Advanced principles in environmental policy. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Endres, A., Friehe, T. The Compensation Regime in Liability Law: Incentives to Curb Environmental Harm, Ex Ante and Ex Post. Environ Resource Econ 62, 105–123 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-014-9817-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-014-9817-5