Abstract

In this paper the dynamic effects of public environmental policies are investigated in a Cournot duopoly with both heterogeneous and homogeneous expectations in a context of limited rationality. It is shown that the increase in upper limits to emissions always tends to destabilise markets and generate a chaotic market dynamics in both cases. The policy implication of this result is that the use of environmental policies may favour market stability. It is also shown that higher costs of abatement technology entail a higher likelihood of stability loss (although in the heterogeneous expectations case also a decrease in costs may destabilise).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Environmental standards are requirements that set specific limits to the amount of pollutants that can be released into the environment by firms. More details are given in the Appendix.

Alternatively, we could assume environmental taxes which are also increasingly implemented by public agencies (European Environment Agency 2000). This is left for further research.

Given the dynamic focus of this paper in a context of disequilibrium dynamics and limited information, we abstract from the choice of “optimal” environmental standards by public agency, as is the rule in the static duopoly games literature. Therefore we study the effects of exogenously given (rather than endogenously—optimally—chosen) environmental standards.

Under the assumption of Cournot-naïve expectations, Theocharis (1959) showed for the standard case with linear demand and cost functions in a homogeneous duopoly that the (quantity) adjustment process always converges to the Nash equilibrium. Since then, the case with naïve expectations has been analysed in depth, taking into consideration alternative features of the demand and cost functions, (see, for instance, Puu 1997), revealing complicated dynamics specifically due to the non-linearity introduced in the alternative demand and cost functions.

The existence, stability and uniqueness of the Cournot oligopoly equilibrium under adaptive expectations was studied by Okuguchi (1976).

Note that there exists another equilibrium, in which firm 1 does not produce and thus firm 2 is a monopolist. Since the focus of the paper is on market stability in a strategic duopolistic context in which both firms compete, monopolistic equilibrium is not analysed here.

Note that, as regards the results presented in the rest of the paper, this inequality holds not only at equilibrium but also for every dynamic path (i.e. \(q(t)\ge e(t)\), with \(t\epsilon (0,\propto ))\). I am grateful to the editor Hassan Benchekroun for having pointed out to me the relevance of such a constraint.

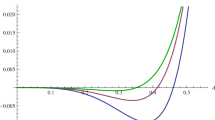

However, while the stability loss of the positive equilibrium is exhaustively analysed through the “stability triangle”, the dynamic behaviour in the “large” after the loss of stability may be more complicated and often investigated only by numerical methods: I refer to Bischi et al. (2010) for a thorough analysis of the dynamics of oligopolies. Also, the global dynamics of the present model is numerically investigated in Sect. 3.2.

The proof of Proposition 3 straightforwardly derives from \(\alpha ^{F}-a^{H}=\frac{(2+k)(3+k)(1-4-k^{2}-4k)}{(a+ek)(5+k^{2}+4k)}<0\).

Note that there are three other equilibrium points, where: (1) neither firm produces; (2) only firm 1 produces; (3) only firm 2 produces (see also footnote 7).

Note that the yellow (red) regions are the basin of attraction of the period-4 regular cycle (four-piece ring-shaped chaotic attractor): the basins appear to be disconnected and to have a fractal dimension.

This list strictly follows the taxonomy reported in the Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution (RCEP), (1998).

References

Agiza HN, Elsadany AA (2003) Nonlinear dynamics in the Cournot duopoly game with heterogeneous players. Phys A 320:512–524

Bárcena-Ruiz JC, Garzón MB (2003) Strategic environmental standards, wage incomes and the location of polluting firms. Environ Res Econ 24:121–139

Bárcena-Ruiz JC, Garzón MB (2006) Mixed oligopoly and environmental policy. Span Econ Rev 8:139–160

Barrett S (1994) Strategic environmental policy and international trade. J Public Econ 54:325–338

Bischi GI, Chiarella C, Kopel M, Szidarovszky F (2010) Nonlinear oligopolies: stability and bifurcations. Springer, Berlin

Bluffstone R, Panayotou T (2000) Environmental liability in central and eastern Europe: toward an optimal policy. Environ Res Econ 17:335–352

Cournot A (1838) Recherches sur les Principes Mathématiques de la Théorie des Richesses. Hachette, Paris

Den Haan WJ (2001) The importance of the number of different agents in a heterogeneous asset-pricing model. J Econ Dyn Control 25:721–746

Dixit AK (1986) Comparative statics for oligopoly. Int Econ Rev 27:107–122

European Environment Agency (2000) Environmental taxes: recent developments in tools for integration. Environmental Issues Series No 18

Fanti L, Gori L (2012) The dynamics of a differentiated duopoly with quantity competition. Econ Model 29(2):421–427

Gandolfo G (2010) Economic Dynamics, 4th edn. Springer, Heidelberg

Hoel M (1997) Environmental policy with endogenous plant locations. Scand J Econ 99:241–259

Katsoulakos Y, Xepapadeas A (1996a) Emission taxes and market structure. In: Carraro C, Katsoulakos Y, Xepapadeas A (eds) Environmental policy and market structure. Kluwer, The Netherlands

Katsoulakos Y, Xepapadeas A (1996b) Environmental innovation, spillovers and optimal policy rules. In: Carraro C, Katsoulacos Y, Xepapadeas A (eds) Environmental policy and market structure. Kluwer, The Netherlands

Kennedy P (1994) Equilibrium pollution taxes in open economies with imperfect competition. J Environ Econ Manag 27:49–63

Leonard D, Nishimura K (1999) Nonlinear dynamics in the Cournot model without full information. Ann Oper Res 89:165–173

Markusen JR (1997) Costly pollution abatement, competitiveness and plant location decisions. Res Energy Econ 19:299–320

Markusen JR, Morey ER, Olewiler N (1995) Competition in regional environmental policies when plant locations are endogenous. J Public Econ 56:55–77

Medio A (1992) Chaotic dynamics: theory and applications to economics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (UK)

Okuguchi K (1976) Expectations and stability in oligopoly models. Lecture notes in economics and mathematical systems, vol 138. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York

Puu T (1997) Nonlinear economic dynamics. Springer, Berlin

Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution (RCEP) (1998) Environmental standards and public values. A summary of the twenty-first report of the royal commission on environmental pollution. The Stationery Office, London

Theocharis RD (1959) On the stability of the Cournot solution on the oligopoly problem. Rev Econ Stud 27:133–134

Tramontana F (2010) Heterogeneous duopoly with isoelastic demand function. Econ Model 27:350–357

Ulph A (1996) Environmental policy and international trade when governments and producers act strategically. J Environ Econ Manag 30:256–281

van der Ploeg F, de Zeeuw AJ (1992) International aspects of pollution control. Environ Res Econ 2:117–139

Zhang J, Da Q, Wang Y (2007) Analysis of nonlinear duopoly game with heterogeneous players. Econ Model 24:138–148

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Although in the paper’s models the environmental standard in question has been represented, as usual, in a stylised way through an allowed level of polluting production, environmental standards may take different forms. They include not only numerical and legally enforceable limits, but standards which may be: (1) not only mandatory but contained in guidelines, codes of practice or sets of criteria for deciding individual cases; (2) not only set by governments but also by entities endowed with a certain degree of authority, such as scientific committees or firms with large market power.

The following is a brief list of the various forms of environmental standards (with corresponding examples):Footnote 13 (1) biological standards: e.g. European Community (EC) reference level for the concentration of lead in blood; (2) exposure standards: e.g. EC dose limits for external radiation; tolerable daily intake of a substance from all routes determined under the International Programme on Chemical Safety; (3) quality standards: e.g. World Health Organization guideline values for air quality; EC quality standards for bathing waters; EC guidelines for heavy metals in agricultural soils; (4) emission standards: e.g. Protocols under the Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe; EC limit values for emissions for road vehicles; (5) product standards, e.g. EC standards for motor fuels; EC limit and guide values for drinking water quality; (6) process standards, e.g. Guidance Notes issued by the Environment Agency for processes subject to Integrated Pollution Control and by the Secretary of State for processes which are regulated by local authorities for emissions to air; (7) life cycle-based standards, e.g. EC ecolabelling scheme; (8) use standards: e.g. bans and restrictions under the EC Marketing and Use Directive; EC and UK procedures for authorising plant protection, industrial chemicals, biocidal and veterinary medicinal products; (9) management standards: e.g. International Organization for Standardization standard ISO 14001 for environmental management systems.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fanti, L. Environmental Standards and Cournot Duopoly: A Stability Analysis. Environ Resource Econ 61, 577–593 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-014-9807-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-014-9807-7