Abstract

Many studies have tested the pollution haven effect (PHE) which predicts that the tightening of local environmental regulations would shift foreign direct investment (FDI) to less regulated jurisdictions. However, most of them ignored the heterogeneity of FDI. This paper studies the PHE on local-market-oriented and export-oriented FDI and tests whether the two types have different responsiveness to environmental regulations in a host country. A simple model is developed to describe how different types of multinational companies respond in distinct ways to stricter environmental policies in host countries. Using US outward FDI data for 50 host countries and a survey measure of both the stringency and the enforcement of local environmental regulations, I find a significant deterrent effect of local environmental regulations on inward FDI. Furthermore, FDI in a host country is not only affected by local environmental regulations but also by environmental regulations in proximate countries. More importantly, accounting for the relative stringency of environmental regulations between a host country and the United States is critical for identifying a PHE. I find a significantly stronger effect of environmental policies on both types of FDI in host countries with environmental regulations that are stricter than those in the United States. In these countries, export-oriented FDI also exhibits a greater sensitivity to local environmental regulations than local market-oriented FDI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The BEA data shows that, in 1999 the sales by US affiliates to foreign countries (other than their host countries) exceeded 10 billion dollars in Latin America and Asia–Pacific. In Europe, such sales exceeded 46 billion dollars, which is about 20 % of the total sales made by US affiliates in Europe.

The derivation of the following equation is provided in the “Appendix”.

Assume that all MNCs produce in \(H\) and there is no environmental cost \(s\), then the sales of a single MNC is \(\frac{A-\hat{c}}{(n+2)B}\). Assuming every MNC has positive sales, we have \(A>\hat{c}\).

These demand functions can be derived from a representative consumer with quadratic utility function \(U(q)=\alpha \sum _{i=1}^nq_i-\frac{1}{2}(\beta \sum _{i=1}^nq_i^2+\gamma \sum _{i=1}^n\sum _{j\ne i}^nq_iq_j)\) where \(\gamma \in (0,\beta )\) represents the substitutability of the products, as in Ledvina and Sircar (2011). The closer \(\gamma \) is to \(\beta \), the more similar the products are to each other. The closer \(\gamma \) is to 0, the more independent the products are. The coefficients \(A\), \(B\) and \(C\) in (12) and (13) refer to \(\frac{\alpha }{\beta +(n-1)\gamma }\), \(\frac{\beta +(n-2)\gamma }{(\beta +(n-1)\gamma )(\beta -\gamma )}\) and \(\frac{\gamma }{(\beta +(n-1)\gamma )(\beta -\gamma )}\), respectively.

The details for arriving at Eq. (18) is provided in the “Appendix”.

In the case that \(Q<0\), \(B-nC\) must be positive. This is because \(Q\) can be rewritten as \(Q=-\frac{1}{2}\theta \left[ (2-\theta )B+(1-\theta )C\right] (B-nC)+\frac{1}{4}\theta nC^2\) and it is assumed that \(0<\theta <1\). If \(B-nC\le 0\), \(Q\) must be positive.

Most scholars agree that affiliate sales is the measure that best describes the actual economic activity of an affiliate. Although data of FDI stock is more prevalent, it is affected by the use of historical values, etc. FDI flows are financial flows so they differ from capital flows in a number of dimensions. Besides, the correlation between affiliate sales and FDI stock is quite high.

The BEA collects comprehensive data on FDI in the United States and US FDI abroad in its annual survey. Data aggregated at the three- and four-digit NAICS level are publicly available. In the analysis, I use sales of majority-owned nonbank affiliates of nonbank US parents. A majority-owned nonbank affiliate is defined as an affiliate for which the combined ownership of all US parents exceeds 50 %.

The list of industries and countries is provided in the “Appendix”.

The countries in each region are listed in the “Appendix”.

The exchange rate is represented by the amount of local currency per US dollar.

The BEA reports in its annual surveys the US direct investment position abroad which measures the cumulative value of US parents’ investment in their foreign affiliates. The position data are reported at industry-by-country level.

Observations of zero sales are transferred to \(\ln (sales+1)\) so that they are not dropped from the sample.

I could not include country dummies as the number of countries is relatively large compared to the number of years in the panel. Canada and Mexico have their own dummies for their special relationship with the United States.

For a host country, other countries refer to the countries in the same region and the characteristics in other countries are weighted by their GDP.

GMM estimator is expected to be more efficient than 2SLS estimator in the presence of heteroskedasticity. The results from 2SLS estimation are not very different from the GMM estimation results.

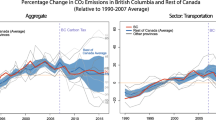

The empirical results are mainly driven by the difference in levels of environmental regulations between countries. As shown in Fig. 1, countries in Europe experienced greater changes in the level of regulatory stringency than those in other regions. To see if different regions exhibit similar patterns of the PHE, I run the regressions in Table 3 for three large regions with enough countries and observations, Europe, Asia–Pacific, and America. The results are shown in the Table 9. In general, the results are consistent with the main results in Table 3. Moreover, Ireland is one of the most successful European countries in attracting export-oriented FDI. Anecdotal evidence suggests that foreign MNCs in Ireland export their products exclusively to other European countries. The results for Europe are not very different with the results from Ireland dropped from the region.

The estimated elasticity for local-market-oriented FDI is 1.57 in Table 3. The average growth rate of regulatory stringency in Ireland and Denmark are 1.29 and 9.30 %, respectively. The economic effect of environmental regulation in Ireland would be a \(1.57*(9.30-1.29)\%\) decrease in local-market-oriented FDI. Similarly, the effect on export-oriented FDI could be calculated as \(3.327*(9.30-1.29)\%\).

To further test the relevance of the instruments, the joint significance of the four instruments in the first stage regressions for each type of FDI is tested. The results are provided in the “Appendix”.

I also use the inverse of distance to weight other countries’ environmental index as a robustness test and the results are similar. The magnitudes of the coefficients on the “third-country” environmental index are slightly larger when using these weights.

The weights are also normalized to sum to 1.

In their view, if the border costs between countries in a region are significant enough, MNCs could locate in the country with the largest own market potential which on the other hand has the smallest “third-country” market potential so as to avoid border costs.

Specifically the instrument variable for the interaction term is the product of tractors per agricultural worker and the index for public school quality.

References

Balasubramanyam V, Salisu M, Sapsford D (1996) Foreign direct investment and growth in EP and IS countries. Econ J 106(434):92–105

Baltagi BH, Egger P, Pfaffermayr M (2007) Estimating models of complex FDI: Are there third-country effects? J Econom 140(1):260–281

Blonigen BA, Davies RB, Waddell GR, Naughton HT (2007) FDI in space: spatial autoregressive relationships in foreign direct investment. Eur Econ Rev 51(5):1303–1325

Borensztein E, De Gregorio J, Lee J (1998) How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth? J int Econ 45(1):115–135

Brunnermeier S, Levinson A (2004) Examining the evidence on environmental regulations and industry location. J Environ Dev 13(1):6

Carr DL, Markusen JR, Maskus KE (2001) Estimating the knowledge-capital model of the multinational enterprise. Am Econ Rev 91(3):693–708

Cole MA, Elliott RJR (2005) FDI and the capital intensity of “dirty” sectors: a missing piece of the pollution haven puzzle. Rev Dev Econ 9(4):530–548

Copeland BR, Taylor MS (1994) North-south trade and the environment. Q J Econ 109(3):755–787

Dean JM, Lovely ME, Wang H (2009) Are foreign investors attracted to weak environmental regulations? Evaluating the evidence from China. J Dev Econ 90(1):1–13

Dijkstra B, Mathew A, Mukherjee A (2007) Environmental regulation: an incentive for FDI (working papers)

Ederington J, Levinson A, Minier J (2004) Trade liberalization and pollution havens. BE J Econ Anal Policy 4(2):6

Ederington J, Minier J (2003) Is environmental policy a secondary trade barrier? An empirical analysis. Can J Econ Revue Can Econ 36(1):137–154

Ekholm K, Forslid R, Markusen JR (2007) Export-platform foreign direct investment. J Eur Econ Assoc 5(4):776–795

Eskeland GS, Harrison AE (2003) Moving to greener pastures? Multinationals and the pollution haven hypothesis. J Dev Econ 70(1):1–23

Greenstone M (2002) The impacts of environmental regulations on industrial activity: evidence from the 1970 and 1977 Clean Air Act Amendments and the census of manufactures. J Polit Econ 110(6):1175–1219

Helpman E (1984) A simple theory of international trade with multinational corporations. J Polit Econ 92(3):451–471

Javorcik BS, Wei S-J (2003) Pollution havens and foreign direct investment: dirty secret or popular myth? BE J Econ Anal Policy 3(2):1-34

Jeppesen T, List JA, Folmer H (2002) Environmental regulations and new plant location decisions: evidence from a meta-analysis. J Reg Sci 42(1):19–49

Kellenberg DK (2009) An empirical investigation of the pollution haven effect with strategic environment and trade policy. J Int Econ 78(2):242–255

Ledvina AF, Sircar R (2011) Bertrand and cournot competition under asymmetric costs: number of active firms in equilibrium. SSRN eLibrary

Levinson A (1996) Environmental regulations and manufacturers’ location choices: evidence from the census of manufactures. J Public Econ 62(1–2):5–29

Levinson A, Taylor MS (2008) Unmasking the pollution haven effect. Int Econ Rev 49(1):223–254

Li X, Liu X (2005) Foreign direct investment and economic growth: an increasingly endogenous relationship. World Dev 33(3):393–407

List JA, Co CY (2000) The effects of environmental regulations on foreign direct investment. J Environ Econ Manag 40(1):1–20

Markusen J (1984) Multinationals, multi-plant economies, and the gains from trade. J Int Econ 16(3–4):205–226

Markusen J (1998) Multinational firms, location and trade. World Econ 21(6):733–756

Markusen JR (2004) Multinational firms and the theory of international trade, volume 1 of MIT Press Books. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Markusen JR, Venables AJ (1998) Multinational firms and the new trade theory. J Int Econ 46(2):183–203

McGuire M (1982) Regulation, factor rewards and international trade. J Public Econ 17(3):335-354

McAusland C (2004) Environmental regulation as export promotion: product standards for dirty intermediate goods. BE J Econ Anal Policy 3(2):7

Monteiro J, Kukenova M (2008) Does lax environmental regulation attract FDI when accounting for “third-country” effects? IRENE (working papers)

Pethig R (1976) Pollution, welfare and environmental policy in the theory of comparative advantage. J Environ Econ and Manage 2(3):160-169

Taylor M (2005) Unbundling the pollution haven hypothesis. BE J Econ Anal Policy 4(2):8

van Beers C, van den Bergh JCJM (1997) An empirical multi-country analysis of the impact of environmental regulations on foreign trade flows. Kyklos 50(1):29–46

Wagner U, Timmins C (2009) Agglomeration effects in foreign direct investment and the pollution haven hypothesis. Environ Resour Econ 43(2):231–256

Xing Y, Kolstad C (2002) Do lax environmental regulations attract foreign investment? Environ Resour Econ 21(1):1–22

Acknowledgments

Previous versions of this paper have been included as part of my doctoral dissertation in economics at Rutgers University and presented in the 2012 ZEW (The Centre for European Economic Research) Summer Workshop for Young Economists. Thanks are due to my dissertation committee: Rosanne Altshuler, Hilary Sigman, Gal Hochman, and Timothy Goodspeed; as well as session participants and anonymous reviewers for comments and suggestions. I also would like to thank Derek Kellenberg for providing useful data. View expressed and all remaining errors are mine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, J. Testing the Pollution Haven Effect: Does the Type of FDI Matter?. Environ Resource Econ 60, 549–578 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-014-9779-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-014-9779-7