Abstract

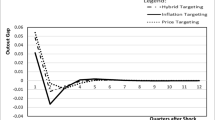

This paper analyzes the implications of incomplete information for the conduct of monetary policy in small-open economy. I use a standard theoretical DSGE model to evaluate the performance of simple rules, including the exchange rate peg. Incomplete information is modeled assuming that the central bank and the private sector observe domestic inflation and output with a measurement error, while they do not observe potential output. I show that not reacting to the exchange rate yields better outcomes in terms of a standard loss function. For the case of complete information and incomplete information, I quantify for which parameter configuration a Taylor rule reacting to both the exchange rate and the domestic inflation rate yields a higher loss than the fixed exchange rate regime.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the conduct of monetary policy, neither the component currencies, their assigned weights in the basket, nor the band limits are disclosed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. Chow et al. (2014) examine the managed exchange rate system in Singapore using a DSGE vector autoregressive approach.

This parameterization of policy coefficients ensures local uniqueness of the equilibrium.

Since the analysis is theoretical, the estimation of shocks refers to the capacity of understanding which shock hits the economy and the size of the shock.

Henceforth, all the matrices introduced will be known conformable matrices.

These two matrices can be found numerically. Computational details, which follow the methodology described in Svensson and Woodford (2003), are available on request.

Even in the case of zero-measurement error, the signal-extraction problem is relevant. The assumption of equal measurement error for domestic output and inflation is without loss of generality. The results do not vary qualitatively if I change the value for the measurement errors.

The results do not vary qualitatively if I change the value for measurement errors.

Benigno et al. (2007) prove this result analytically.

The simulated model is a theoretical VAR according to the structure (7), enriched with the measurement equation (9) in the case of incomplete information. Therefore in the simulation the starting point is the steady state, which is shocked in order to analyze the on impact response and the transition back to the steady state.

As noticed before, the shock to foreign output can be estimated using the \(\textit{IS}\) equation.

References

Adolfson, M., Laséen, S., Lindé, J., & Villani, M. (2007). Bayesian estimation of an open economy DSGE model with incomplete pass-through. Journal of International Economics, 72(2), 481–511.

Benigno, G., Benigno, P., & Ghironi, F. (2007). Interest rate rules for fixed exchange rate regimes. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 31(7), 2196–2211.

Berger, W. (2006). The choice bewteen fixed and flexible exchange rates: Which is the best for small open economy? Journal of Policy Modeling, 28, 371–385.

Calvo, G., & Reinhart, C. (2002). Fear of floating. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(2), 379–408.

Chow, H. K., Lim, G., & McNelis, P. D. (2014). Monetary policy choice in Singapore: Would a Taylor rule outperform exchange-rate management? Journal of Asian Economics, 30, 63–81.

Cukierman, A., & Lippi, F. (2005). Endogenous monetary policy with unobserved potential output. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 29, 1951–1983.

Dennis, R., & Ravenna, F. (2008). Learning and optimal monetary policy. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 32, 1964–1994.

Dennis, R., Leitemo, K., & Söderström, U. (2009). Methods for robust control. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 33(8), 1604–1616.

Di Giorgio, G., & Traficante, G. (2013). The loss from uncertainty on policy targets. Economic Modelling, 32, 1964–1994.

Ehrmann, M., & Smets, F. (2003). Uncertain potential output: Implications for monetary policy. Economic Modelling, 30, 175–182.

Galí, J., & Monacelli, T. (2005). Monetary policy and exchange rate volatility in a small open economy. The Review of Economic Studies, 72(3), 707–734.

Giavazzi, F., & Pagano, M. (1988). The advantage of tying one’s hands. European Economic Review, 32, 1055–1082.

Leitemo, K., & Söderstrom, U. (2005). Simple monetary policy rules and exchange rate uncertainty. Journal of International Money and Finance, 24, 481–507.

Melecký, M., Palenzuela, D. R., & Söderström, U. (2009). Inflation target transparency and the macroeconomy. Series on Central Banking, analysis, and economic policies. (Vol. XIII, pp. 371–411). Santiago: Central Bank of Chile.

Monacelli, T. (2004). Commitment, discretion and fixed exchange rates in an open economy. In J. O. Hairault & T. Sopraseuth (Eds.), Exchange rate dynamics: An open economy macroeconomics perspective. London: Routledge.

Orphanides, A. (2001). Monetary policy rules based on real-time data. The American Economic Review, 91(4), 964–985.

Orphanides, A. (2003). The quest for prosperity without inflation. Journal of Monetary Economics, 50, 633–663.

Ravenna, F. (2012). Why join a currency union? A note on the impact of beliefs on the choice of monetary policy. Macroeconomic Dynamics, 16, 320–334.

Soffritti, M., & Zanetti, F. (2008). The advantage of tying one’s hands: Revisited. International Journal of Finance and Economics, 13, 135–149.

Svensson, L. E. O., & Woodford, M. (2003). Indicator variables for optimal policy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 50, 691–720.

Tkacz, G. (2010). An uncertain past: Data revisions and monetary policy in Canada. Bank of Canada Review, Spring, 41–51.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper previously circulated with the title “Choosing the exchange rate system with incomplete information”. The very first version of the paper was written while I was visiting the department of economics at the University of California Santa Cruz. I am grateful for the department’s hospitality. I thank Daniel Beltran, Helde Berger, Giorgio Di Giorgio, Mathias Hoffmann, Federico Ravenna Abhijit Sen Gupta and Carl Walsh for their insightful comments. Any remaining errors are, of course, my sole responsibility.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Traficante, G. Uncertain Potential Output and Simple Rules in Small Open Economy. Comput Econ 50, 517–531 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10614-016-9601-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10614-016-9601-4