Abstract

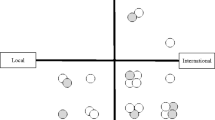

Case studies show that there are at least two types of groups involved in phishing: low-tech all-rounders and high-tech specialists. However, empirical criminological research into cybercriminal networks is scarce. This article presents a taxonomy of cybercriminal phishing networks, based on analysis of 18 Dutch police investigations into phishing and banking malware networks. There appears to be greater variety than shown by previous studies. The analyzed networks cannot easily be divided into two sharply defined categories. However, characteristics such as technology use and offender-victim interaction can be used to construct a typology with four overlapping categories: from low-tech attacks with a high degree of direct offender-victim interaction to high-tech attacks without such interaction. Furthermore, clear differences can be distinguished between networks carrying out low-tech attacks and high-tech attacks. Low-tech networks, for example, make no victims in other countries and core members and facilitators generally operate from the same country. High-tech networks, on the contrary, have more international components. Finally, networks with specialists focusing on one type of crime are present in both low-tech and high-tech networks. These specialist networks have more often a local than an international focus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

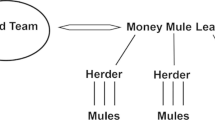

In cybercrime literature, the term ‘money mule’ is often used to describe these offenders (see Choo [2]; McCombie [17]; Aston et al. [1]; [15, 20]). In our opinion, ‘money mule’ is not entirely the right term as these offenders are not used to physically move money from one place to another, but instead solely to disguise the financial trail from victims’ bank accounts leading back to the core members (see Leukfeldt et al. [16] for a more comprehensive description). As the term money mule is so widely used, we have chosen to use it in this article.

Money from the victims’ accounts can also be cashed in other ways. Criminals, for example, also buy goods or Bitcoins directly from the victims’ accounts. However, all networks mainly used accounts of bogus men to get the money.

References

Aston, M., McCombie, S., Reardon, B. & Watters, P. (2009) A preliminary profiling of internet money mules: an Australian perspective. Proceedings of the 2009 Symposia and Workshops on Ubiquitous, Autonomic and Trusted Computing, IEEE Computer Society, 482–487.

Choo, K.K.R. (2008). Organised crime groups in cyberspace: aa typology. Trends in Organized Crime, 3(11), 270–295.

Felson, M. (2003). The process of co-offending. In M. J. Smith & D. B. Cornish (Eds.), Theory for practice in situational crime prevention (volume 16) (pp. 149–168). Devon: Willan Publishing.

Felson, M. (2006) The ecosystem for organized crime (HEUNI paper nr 26). Helsinki: HEUNI.

Grabosky, P. N. (2004). The global dimensions of cybercrime. Global Crime, 6(1), 146–157.

Holt, T. J., & Bossler, A. M. (2014). An assessment of the current state of cybercrime scholarship. Deviant Behavior, 35(2014), 20–40.

Kleemans, E. R. (2007). Organized crime, transit crime, and racketeering. Crime and Justice. A Review of Research, 35, 163–215.

Kleemans, E. R. (2014). Organized Crime Research: Challenging Assumptions and Informing Policy. In J. Knutsson & E. Cockbain (Eds.), Applied Police Research: Challenges and Opportunities. Crime Science Series. Cullompton: Willan.

Kleemans, E. R., & De Poot, C. J. (2008). Criminal careers in organized crime and social opportunity structure. European Journal of Criminology, 5(1), 69–98.

Kleemans, E. R., & Van de Bunt, H. G. (1999). The social embeddedness of organized crime. Transnational Organized Crime, 5(2), 19–36.

Kleemans, E.R., Van der Berg, A.E.I.M. & Van de Bunt, H.G. (1998). Georganiseerde criminaliteit in Nederland. Rapportage op basis van de WODC monitor. [Organized crime in the Netherlands] Den Haag: WODC.

Kleemans, E.R., Brienen, M.E.I., Van de Bunt, H.G., Kouwenberg, R.F., Paulides, G. and Barensen, J. (2002) Georganiseerde criminaliteit in Nederland. Ttweede rapportage op basis van de WODC-monitor. [Second report on organized crime in the Netherlands] Den Haag: WODC.

Kruisbergen, E.W., Van de Bunt, H.G., Kleemans, E.R. and Kouwenberg, R.F. (2012) Georganiseerde criminaliteit in Nederland. Vierde rapportage op basis van de Monitor Georganiseerde Criminaliteit. [Fourth report on organized crime in the Netherlands] Den Haag: Boom Lemma.

Lastdrager, E. E. H. (2014). Achieving a consensual definition of phishing based on a systematic review of the literature. Crime Science, 3(9), 1–6.

Leukfeldt, E.R. (2014). Cybercrime and social ties. Phishing in Amsterdam. Trends in Organized Crime, 17(4), 231–249.

Leukfeldt, E.R., Kleemans, E.R., and Stol, W.P. (2016) Cybercriminal Networks, Social Ties and Online Forums: Social Ties Versus Digital Ties within Phishing and Malware Networks British Journal of Criminology (accepted for publication / online first).

McCombie, S.J. (2011). Phishing the long line. Transnational cybercrime from Eastern Europe to Australia. (PhD-thesis). Sydney: Macquarie University

McGloin, J. M., & Kirk, D. S. (2010). An overview of social network analysis. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 21(2), 169–181.

Scott, J., & Carrington, P. J. (2011). The SAGE Handbook of Social Network Analysis. London: SAGE Publications.

Soudijn, M. R. J., & Zegers, B. C. H. T. (2012). Cybercrime and virtual offender convergence settings. Trends in Organized Crime, 15(2–3), 111–129.

van de Bunt, H.G. and E.R. Kleemans (2007) Georganiseerde criminaliteit in Nederland, derde rapportage op basis van de Monitor Georganiseerde Criminaliteit. [3rd report on organised crime in the Netherlands] Den Haag: WODC.

Wall, D. S. (2007). Cybercrime. The Transformation of Crime in the Information Age. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leukfeldt, E.R., Kleemans, E.R. & Stol, W.P. A typology of cybercriminal networks: from low-tech all-rounders to high-tech specialists. Crime Law Soc Change 67, 21–37 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-016-9662-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-016-9662-2