Abstract

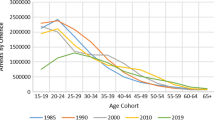

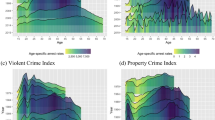

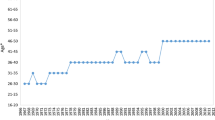

Studies have shown the impact of a population’s age structure on the crime rate. Germany is — like many other industrialized countries — facing an ageing of its population. This trend will continue in the future: Until the year 2020 the share of younger people aged 14 to 24 years will decrease from 12.3 % to 10.7 % and the share of elderly persons aged 60 years and older will increase from 25.9 % to 30.1 %. Crime is, however, not only influenced by age, other factors also play an important role. Research has shown that the level of social disorganization is especially related to the crime rate. The aim of the present contribution is to explain the crime trends between 1995 and 2010 using multivariate panel estimators that take into account the demographic changes and social disorganization. These models are in a second step used to forecast the crime trends until the year 2020. The data base consists of pooled time-series at the county level from four German states (Bavaria, Brandenburg, Lower Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt). The results show that the age structure plays only a limited role in explaining the past crime trends. The most important factor is residential instability. The forecasts expect a decline of the number of registered offences till 2020. However, the decline will be faster in the eastern states than in the western states and some offences are expected to increase in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The figures are based on data from the German Federal Statistical Agency. The population forecasts are derived from the 12th Coordinated Population Forecast from the German Federal Statistical Agency (www.destatis.de).

A more detailed representation of the methodology and the results can be found in Hanslmaier et al. (2014).

For an overview on other approaches, see Berk (2008).

We renounce to present tables of descriptive and bivariate statistics of the crime rates and the independent variables, because simple descriptive statistics and correlation tables cannot take into account the two-dimensional structure of the data. A disaggregated representation by state and dimension, however, would require too much space. These tables are available upon request from the corresponding author.

This strategy is, for example, also used by Metz and Sohn (2008).

For a detailed description see Hanslmaier et al. (2014, pp. 205-218).

The 2009 data were latest available data for inmates.

References

Adolph, C., Butler, D. M., & Wilson, S. E. (2005). Like shoes and shirt, one size does not fit all: Evidence on time series cross-section estimators and specifications from monte carlo experiments. 101st annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Washington, DC.

Baier, D., & Hanslmaier, M. (2013). Demografische Entwicklung und Prognose der Kriminalität [Demographic trends and forecasting crime. Extrapolations are not Enough]. Kriminalistik, 67(10), 587–594.

Baier, D., Pfeiffer, C., Rabold, S., Simonson, J., & Kappes, C. (2010). Kinder und Jugendliche in Deutschland: Gewalterfahrungen, Integration, Medienkonsum [Children and youths in Germany: Experience of violence, integration, media consumption]. In KFN Research Report No. 109. Hannover: KFN.

Baltagi, B. H. (2008). Forecasting with panel data. Journal of Forecasting, 27(2), 153–173.

Baum, C. F. (2006). An Introduction to Modern Econometrics Using Stata. College Station: Stata Press.

Beck, N., & Katz, J. N. (1995). What to do (and not to do) with Time-Series Cross-Section Data. The American Political Science Review, 89(3), 634–647.

Beck, N., & Katz, J. N. (2011). Dynamics in time series cross section data. Annual Review of Political Science, 14(1), 331–352.

Berk, R. (2008). Forecasting methods in crime and justice. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 4, 219–238.

Bowers, K. J., Johnson, S. D., & Pease, K. (2004). Prospective hot-spotting: the future of crime mapping? British Journal of Criminology, 44, 641–658.

Bruno, G. S. F. (2005). Estimation and inference in dynamic unbalanced panel-data models with a small number of individuals. Stata Journal, 5(4), 473–500.

Bursik, R. J. (1988). Social disorganization and theories of crime and delinquency - problems and prospects. Criminology, 26(4), 519–551.

Bursik, R. J., & Grasmick, H. G. (1993). Neighbourhood and crime: The dimensions of effective community control. New York: Lexington Books.

Carrington, P. J. (2001). Population aging and crime in Canada, 2000–2041. Canadian Journal of Criminology, 43(3), 331–356.

Chen, P., Yuan, H. Y., & Shu, X. M. (2008). Making weekly/daily forecasting of property crime using ARIMA model. Progress in Safety Science and Technology, Parts A and B, 7, 531–535.

Clements, M. P., & Witt, R. (2005). Forecasting quarterly aggregate crime series. Manchester School, 73(6), 709–727.

Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: a routine activity approach. American Sociological Review, 44(4), 588–608.

Cohen, L. E., Felson, M., & Land, K. C. (1980). Property crime rates in the United States: a macrodynamic analysis, 1947–1977; with ex ante forecasts for the mid-1980s. American Journal of Sociology, 86(1), 90–118.

Deadman, D. F. (2003). Forecasting residential burglary. International Journal of Forecasting, 19(4), 567–578.

Dhiri, S., Brand, S., Harries, R., & Price, R. (1999). Modelling and predicting property home office research studies. Home Office Research Study No. 198. London: Home Office.

Entorf, H., & Spengler, H. (2000). Socioeconomic and demographic factors of crime in Germany. Evidence from panel data of the German states. International Review of Law and Economics, 20(2000), 75–106.

Felson, M. (1986). Linking criminal choices, routine activities, informal control, and criminal outcomes. In D. B. Cornish & R. V. Clarke (Eds.), The reasoning criminal. Rational choice perspectives on offending (pp. 119–128). New York: Springer.

Fox, J. A., & Piquero, A. R. (2003). Deadly demographics: population characteristics and forecasting homicide trends. Crime & Delinquency, 49(3), 339–359.

Gluba, A., & Wolter, D. (2009). Nachwuchssorgen bei der Kriminalität? Demografische Einflüsse auf die Kriminalitätsentwicklung. [Worries about new blood for crime? Demographic influence on crime trends.]. Kriminalistik, 63(5), 284–291.

Gujarati, D. N. (2004). Basic econometrics (4th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Hanslmaier, M., Kemme, S., Stoll, K., & Baier, D. (2014). Kriminalität im Jahr 2020. Erklärung und Prognose registrierter Kriminalität in Zeiten demografischen Wandels. [Crime in the year 2020. Explaning and forecasting crime in times of demografic changes]. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

Harris, K. M., Duncan, G. J., & Boisjoly, J. (2002). Evaluating the role of “nothing to lose” attitudes on risky behavior in adolescence. Social Forces, 80(3), 1005–1039.

Hasenpusch, B. (1979). Future trends of crime in Canada. Canadian Police College Journal, 3(2), 89–114.

Hirschi, T. (1969). Causes of delinquency. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hirschi, T., & Gottfredson, M. R. (1983). Age and the explanation of crime. The American Journal of Sociology, 89(3), 552–584.

Kasarda, J. D., & Janowitz, M. (1974). Community attachment in mass society. American Sociological Review, 39(3), 328–339.

Kaylen, M.T., & Pridemore, W.A. (2013). Social disorganization and crime in rural communities: the first direct test of the systemic model. British Journal of Criminology, 1–19.

Kittel, B. (1999). Sense and sensitivity in pooled analysis of political data. European Journal of Political Research, 35(2), 225–253.

Kiviet, J. F. (1995). On bias, inconsistency, and efficiency of various estimators in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 53–78.

Kornhauser, R. R. (1978). Social sources of delinquency. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kröhnert, S., & Lindner, P. (2009). Regionalanalyse zur Kriminalitätsentwicklung in Brandenburg [Regional analysis of the crime trends in Brandenburg]. Berlin: Berlin Institut für Bevölkerung und Entwicklung.

Lee, M. T., & Martinez, R. (2002). Social disorganization revisited: mapping the recent immigration and black homicide relationship in Northern Miami. Sociological Focus, 35(4), 363–380.

Lee, M. T., Martinez, R., & Rosenfeld, R. (2001). Does immigration increase homicide? Negative evidence from three border cities. Sociological Quarterly, 42(4), 559–580.

Levitt, S. D. (1999). The limited role of changing age structure in explaining aggregate crime rates. Criminology, 37(3), 581–597.

Lochner, L., & Moretti, E. (2004). The effect of education on crime: evidence from prison inmates, arrests, and self-reports. The American Economic Review, 94(1), 155–189.

Lowenkamp, C. T., Cullen, F. T., & Pratt, T. C. (2003). Replicating Sampson and Groves's test of social disorganization theory: revisiting a criminological classic. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 40(4), 351–373.

Marvell, T. B., & Moody, C. E. (1991). Age structure and crime rates: the conflicting evidence. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 7(3), 237–273.

McCall, P. L., Land, K. C., & Parker, K. F. (2011). Heterogeneity in the rise and decline of city-level homicide rates, 1976–2005: a latent trajectory analysis. Social Science Research, 40(1), 363–378.

McCall, P. L., Land, K. C., Dollar, C. B., & Parker, K. F. (2013). The age structure-crime rate relationship: solving a long-standing puzzle. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 29(2), 167–190.

Metz, R., & Sohn, W. (2008). Ist der tiefste Stand schon erreicht? Eine Untersuchung zur Entwicklung der Strafgefangenenzahlen im Auftrag der Justizbehörde der Freien und Hansestadt Hamburg. [Is the lowest level already reached? Analysis of the development of the number of inmates for the Justice Service of the City of Hamburg]. Wiesbaden: Kriminologische Zentralstelle.

Moolenaar, D. E. G., Choenni, S. R., & Leeuw, F. (2007). Design and implementation of a forecasting tool of justice chains. In Proceedings of the Fifth IASTED International Conference on Law and Technology (pp. 60–66). Berkeley: ACTA.

Nickell, S. (1981). Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econometrica, 49(6), 1417–1426.

Nunley, J. M., Seals, R. A., & Zietz, J. (2011). Demographic change, macroeconomic conditions, and the murder rate: the case of the United States, 1934–2006. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 40(6), 942–948.

Pepper, J. V. (2008). Forecasting crime: A city-level analysis. In Committee on Understanding Crime & Trends (Ed.), Understanding crime trends: Workshop report (pp. 177–209). Washington, D.C: National Academies Press.

Plümper, T., & Troeger, V. E. (2009). Fortschritte in der Paneldatenanalyse: Alternativen zum de facto Beck-Katz-Standard [Progress in the analysis of panel data: Alternatives to the de facto Beck-Katz-Standard]. In S. Pickel, G. Pickel, H.-J. Lauth, & D. Jahn (Eds.), Methoden der vergleichenden Politik-und Sozialwissenschaft. Neue Entwicklungen und Anwendungen (pp. 263–276). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Pratt, T. C., & Cullen, F. T. (2005). Assessing macro-level predictors and theories of crime: a meta-analysis. Crime and Justice, 32, 373–450.

Sampson, R. J. (1987). Urban black violence: the effect of male joblessness and family disruption. American Journal of Sociology, 93, 348–382.

Sampson, R. J., & Groves, W. B. (1989). Community structure and crime: testing social-disorganization theory. American Journal of Sociology, 94(4), 774–802.

Schmalensee, R., Stoker, T. M., & Judson, R. A. (1998). World carbon dioxide emissions: 1950–2050. Review of Economics and Statistics, 80(1), 15–27.

Shaw, C. R., & McKay, H. D. (1969). Juvenile Delinquency in Urban Areas (Revisedth ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Short, J. L. (1998). Predictors of substance use and mental health of children of divorce. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 29(January 2015), 147–166.

South, S. J., & Messner, S. F. (2000). Crime and demographie: multiple linkages, reciprocal relations. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 83–106.

Spiess, G. (2009). Demografischer Wandel und altersspezifische Kriminalität. Projektion der Entwicklung bis 2050 [Demografic change and age-specific crime. Projection of the trends up to 2050]. Materialen zur Bevölkerungswissenschaft, 128, 35–56.

Startz, R. (2009). Eviews illustrated for version 7 (2nd ed.). Irvine: Quantitative Micro Software.

Steffensmeier, D. J., Allan, E. A., Harer, M. D., & Streifel, C. (1989). Age and the distribution of crime. American Journal of Sociology, 94(4), 803–831.

Sun, I. Y., Triplett, R. A., & Gainey, R. R. (2004). Neighborhood characteristics and crime : a test of Sampson and Groves’ model of social disorganization. Western Criminology Review, 5(1), 1–16.

Tomeh, A. K. (1973). Formal voluntary organizations: participation, correlates, and interrelationships. Sociological Inquiry, 73(3–4), 89–122.

Veysey, B. M., & Messner, S. F. (1999). Further testing of social disorganization theory: an elaboration of Sampson and Groves’s “Community Structure and Crime.”. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 36(2), 156–174.

Waldron, M., Vaughan, E. L., Bucholz, K. K., Lynskey, M. T., Sartor, C. E., Duncan, A. E., Madden, P. A. F., & Heath, A. C. (2014). Risks for early substance involvement associated with parental alcoholism and parental separation in an adolescent female cohort. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 138, 130–136.

Wilson, S. E., & Butler, D. M. (2007). A lot more to do: the sensitivity of time-series cross-section analyses to simple alternative specifications. Political Analysis, 15(2), 101–123.

Zeratsion, H., Bjertness, C. B., Lien, L., Haavet, O. R., Dalsklev, M., Halvorsen, J. A., Bjertness, E., & Claussen, B. (2014). Does parental divorce increase risk behaviors among 15/16 and 18/19 year-old Adolescents? A study from Oslo, Norway. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 10, 59–66.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments on this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Dr.Kemme is a professor of University of Hamburg.

Baier and Hanslmaier hold PhDs, Criminological Research Institute of Lower Saxony.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hanslmaier, M., Kemme, S., Stoll, K. et al. Forecasting Crime in Germany in Times of Demographic Change. Eur J Crim Policy Res 21, 591–610 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-015-9270-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-015-9270-1