Abstract

Previous research suggests that socially anxious individuals perceive observable signs of social anxiety (SA) as being interpersonally costly and indicative of having less positive attributes, such as strength of character and attractiveness. In the current study, female participants with high (n = 60) versus low (n = 59) levels of trait SA imagined a hypothetical interaction with a male social partner and rated their impressions of this partner across five desirable attributes (ambition, happiness, strength of character, achievement, and intelligence), both before and after the partner was described as appearing either visibly anxious or confident. Results suggested that while both high and low SA participants perceived observable symptoms of anxiety as being interpersonally undesirable, the two groups differed significantly in their appraisals of observable social confidence, with high but not low SA participants attributing highly positive characteristics to confident partners relative to baseline. Combined with their perception that observable anxiety is undesirable, high SA participants’ idealized perception of confident partners as being “larger than life” may contribute to persistent feelings of inferiority and expectations of criticism and rejection in social encounters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

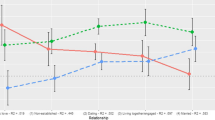

For the ratings of individual attributes that comprise the composite desirability index in the anxious partner condition, there were significant main effects of time for four of the five attributes, including strength of character, ambition, achievements, and happiness, F’s > 8.25, p’s < .01, \( \eta_{p}^{2} \) > .13. In these cases, the ratings across desirable characteristics decreased significantly from baseline to post-manipulation. For intelligence, there was no main effect of time, F(1,57) = .15, p = .90. There were significant main effects of group for strength of character and intelligence, F’s > 4.27, p’s < .04, \( \eta_{p}^{2} \) > .07. In these cases, low SA participants provided lower ratings overall. There were no group × time interactions for any of the desirable characteristics F’s < 2.03, p’s > .16. For the ratings of individual attributes that comprise the aggregated desirability index in the confident partner condition, there were significant main effects of time for two of the five attributes, including intelligence and strength of character, F’s > 17.44, p’s < .001, \( \eta_{p}^{2} \) > .23. There were no significant main effects of time for ambition, achievement, or happiness, F’s < 2.52, p’s > .12. There were no significant main effects of group for any of the desirable attributes rated by participants, F’s < 3.97, p’s > .51. In each of the five desirable characteristics, there were significant group by time interactions, F’s > 4.04, p’s < .05, \( \eta_{p}^{2} \) > .07. Follow-up paired t-tests were conducted separately on scores on each of the attributes. For four of the five attributes (ambition, happiness, intelligence, and achievement), the ratings of low SA individuals did not change significantly from baseline to post-manipulation, all t’s < 1.48, p’s > .15. Conversely, the ratings provided by high SA participants on all five attributes increased significantly from baseline to post-manipulation, all t’s > 2.49, p’s < .02. Although the ratings of low SA participants on strength of character increased significantly from baseline to post-manipulation, t(28) = 3.28, p = .003, the ratings of high SA participants increased more sharply, t(28) = 6.90, p < .001 and were significantly higher at post-manipulation than those of low SA participants, t(57) = 2.10, p = .04, despite not having differed at baseline, t(56) = .68, p = .25. Means and SDs are presented in Table 2.

Adjusted values for degrees of freedom were used because the assumption of equality of variance was violated for this test (i.e., Levene’s test yielded a significant p value).

References

Alden, L. E., & Bieling, P. (1998). Interpersonal consequences of the pursuit of safety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(1), 53–64. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00072-7.

Alden, L. E., Mellings, T. M. B., & Ryder, A. G. (2001). Social anxiety, social phobia, and the self. In S. G. Hofmann & P. M. DiBartolo (Eds.), From social anxiety to social phobia: Multiple perspectives. Needham Heights, MA, US: Allyn & Bacon.

Alden, L. E., & Taylor, C. T. (2004). Interpersonal processes in social phobia. Clinical Psychology Review, 24(7), 857–882. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2004.07.006.

Alden, L. E., & Wallace, S. T. (1995). Social phobia and social appraisal in successful and unsuccessful social interactions. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(5), 497–505. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(94)00088-2.

Antony, M. M., Coons, M. J., McCabe, R. E., Ashbaugh, A., & Swinson, R. P. (2006). Psychometric properties of the social phobia inventory: Further evaluation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(8), 1177–1185. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.08.013.

Antony, M. M., Rowa, K., Liss, A., Swallow, S. R., & Swinson, R. P. (2005). Social comparison processes in social phobia. Behavior Therapy, 36(1), 65–75. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80055-3.

Ashbaugh, A. R., Antony, M. M., McCabe, R. E., Schmidt, L. A., & Swinson, R. P. (2005). Self-evaluative biases in social anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 29(4), 387–398. doi:10.1007/s10608-005-2413-9.

Bielak, T., & Moscovitch, D. A. (2012). Friend or foe? Memory and expectancy biases for faces in social anxiety. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology, 3(1), 42–61. doi:10.5127/jep.19711.

Chu, S., Farr, D., Muñoz, L. C., & Lycett, J. E. (2011). Interpersonal trust and market value moderates the bias in women’s preferences away from attractive high-status men. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(2), 143–147. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.03.033.

Clark, D. M., & Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia. In R. G. Heimberg, M. R. Liebowitz, D. A. Hope, & F. R. Schneier (Eds.), Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment and treatment (pp. 69–93). New York, NY: Guilford.

Connor, K. M., Davidson, J. R. T., Churchill, L. E., Sherwood, A., Foa, E., & Weisler, R. H. (2000). Psychometric properties of the social phobia inventory (SPIN): New self-rating scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 176, 379–386. doi:10.1192/bjp.176.4.379.

Eagly, A. H., Ashmore, R. D., Makhijani, M. G., & Longo, L. C. (1991). What is beautiful is good, but…: A meta-analytic review of research on the physical attractiveness stereotype. Psychological Bulletin, 110(1), 109–128. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.109.

Foa, E. B., Franklin, M. E., Perry, K. J., & Herbert, J. D. (1996). Cognitive biases in generalized social phobia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 105(3), 433–439. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.105.3.433.

Gee, B. A., Antony, M. M., Koerner, N., & Aiken, A. (2012). Appearing anxious leads to negative judgements by others. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(3), 304–318. doi:10.1002/jclp.20865.

Gilboa-Schechtman, E., Franklin, M. E., & Foa, E. B. (2000). Anticipated reactions to social events: Differences among individuals with generalized social phobia, obsessive compulsive disorder, and nonanxious controls. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 24(6), 731–746. doi:10.1023/A:1005595513315.

Gilovich, T., Savitsky, K., & Medvec, V. H. (1998). The illusion of transparency: Biased assessments of others ability to read ones emotional states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(2), 332–346. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.2.332.

Heerey, E. A., & Kring, A. M. (2007). Interpersonal consequences of social anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116(1), 125–134. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.125.

Hertel, P. T., Brozovich, F., Joormann, J., & Gotlib, I. H. (2008). Biases in interpretation and memory in generalized social phobia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117(2), 278–288. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.278.

Hofmann, S. G. (2007). Cognitive factors that maintain social anxiety disorder: A comprehensive model and its treatment implications. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 36(4), 193–209. doi:10.1080/16506070701421313.

Leary, M. R., & Kowalski, R. M. (1995). The self-presentation model of social phobia. In R. G. Heimberg, M. R. Liebowitz, D. A. Hope, & F. R. Schneier (Eds.), Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press.

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U.

Mahone, E. M., Bruch, M. A., & Heimberg, R. G. (1993). Focus of attention and social anxiety: The role of negative self-thoughts and perceived positive attributes of the other. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 17(3), 209–224. doi:10.1007/BF01172946.

Moscovitch, D. A. (2009). What is the core fear in social phobia? A new model to facilitate individualized case conceptualization and treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 16(2), 123–134. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2008.04.002.

Moscovitch, D. A., & Hofmann, S. G. (2007). When ambiguity hurts: Social standards moderate self-appraisals in generalized social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(5), 1039–1052. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2006.07.008.

Moscovitch, D. A., Orr, E., Rowa, K., Reimer, S. G., & Antony, M. M. (2009). In the absence of rose-colored glasses: Ratings of self-attributes and their differential certainty and importance across multiple dimensions in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(1), 66–70. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2008.10.007.

Moscovitch, D. A., Rodebaugh, T. L., & Hesch, B. D. (2012). How awkward! Social anxiety and the perceived consequences of social blunders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(2), 142–149. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2011.11.002.

Moser, J. S., Hajcak, G., Huppert, J. D., Foa, E. B., & Simons, R. F. (2008). Interpretation bias in social anxiety as detected by event-related brain potentials. Emotion, 8(5), 693–700. doi:10.1037/a001317.

Papsdorf, M., & Alden, L. (1998). Mediators of social rejection in social anxiety: Similarity, self-disclosure, and overt signs of anxiety. Journal of Research in Personality, 32(3), 351–369. doi:10.1006/jrpe.1998.2219.

Plasencia, M. L., Alden, L. E., & Taylor, C. T. (2011). Differential effects of safety behaviour subtypes in social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(10), 665–675. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2011.07.005.

Purdon, C., Antony, M., Monteiro, S., & Swinson, R. P. (2001). Social anxiety in college students. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 15(3), 203–215. doi:10.1016/S0887-6185(01)00059-7.

Rapee, R. M., & Heimberg, R. G. (1997). A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(8), 741–756. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00022-3.

Roth, D., Antony, M. M., & Swinson, R. P. (2001). Interpretations for anxiety symptoms in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 39(2), 129–138. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00159-X.

Sparrevohn, R. M., & Rapee, R. M. (2009). Self-disclosure, emotional expression and intimacy within romantic relationships of people with social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(12), 1074–1078. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.016.

Stopa, L., & Clark, D. M. (1993). Cognitive processes in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 31(3), 255–267. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(93)90024-O.

Taylor, C. T., & Alden, L. E. (2008). Self-related and interpersonal judgment biases in social anxiety disorder: Changes during treatment and relationship to outcome. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 1(2), 125–137. doi:10.1521/ijct.2008.1.2.125.

Voncken, M. J., Alden, L. E., & Bögels, S. M. (2006). Hiding anxiety versus acknowledgment of anxiety in social interaction: Relationship with social anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(11), 1673–1679. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.11.005.

Wallace, S. T., & Alden, L. E. (1991). A comparison of social standards and perceived ability in anxious and nonanxious men. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 15(3), 237–254. doi:10.1007/BF01173016.

Weisman, O., Aderka, I. M., Marom, S., Hermesh, H., & Gilboa-Schechtman, E. (2011). Social rank and affiliation in social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(6–7), 399–405. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2011.03.010.

Wenzel, A., & Emerson, T. (2009). Mate selection in socially anxious and nonanxious individuals. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28(3), 341–363. doi:10.1521/jscp.2009.28.3.341.

Wenzel, A., Graff-Dolezal, J., Macho, M., & Brendle, J. R. (2005). Communication and social skills in socially anxious and nonanxious individuals in the context of romantic relationships. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(4), 505–519. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2004.03.010.

Wilson, J. K., & Rapee, R. M. (2005a). Interpretative biases in social phobia: Content specificity and the effects of depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 29(3), 315–331. doi:10.1007/s10608-005-2833-6.

Wilson, J. K., & Rapee, R. M. (2005b). The interpretation of negative social events in social phobia with versus without comorbid mood disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 19(3), 245–274. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.03.003.

Wilson, J. K., & Rapee, R. M. (2006). Self-concept certainty in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), 113–136. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bielak, T., Moscovitch, D.A. How Do I Measure Up? The Impact of Observable Signs of Anxiety and Confidence on Interpersonal Evaluations in Social Anxiety. Cogn Ther Res 37, 266–276 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-012-9473-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-012-9473-4