Abstract

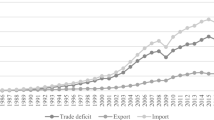

The paper presents an agent-based simulation model of the European defence industry. The model resembles some of the key characteristics of the defence sector, and studies how firms in this market will respond to the challenges and opportunities provided by a higher degree of openness and liberalization in the future. The simulation analysis points out that European defence firms will progressively become more efficient, less dependent on public procurement and innovation policy support, and more prone to knowledge sharing and inter-firm collaborations. This firm-level dynamics will in the long-run lead to an increase in the industry’s export propensity and a less concentrated export market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A survey of this new strand of models is presented by Castellacci (2011).

The Appendix points out in further details the specific changes we have introduced and new aspects we have added to the original SKIN model.

An accurate overview and classification of the different technological fields covered by firms in the defence industry is provided by the taxonomy developed by the European Defence Agency (EDA; see: http://www.eda.europa.eu).

Related to user-producer interactions and international collaborations, another important factor that affects countries’ export propensity is the interoperability with other nations’ equipment. A high interoperability between two countries’ defence equipment, due e.g. to complementary specialization profiles and/or close political ties, may substantially increase cross-border defence trade between them.

An extensive presentation of this approach along with a complete list of project activities and publications is available on the SKIN model’s website: http://cress.soc.surrey.ac.uk/skin/home.

In the original version of the SKIN model, the knowledge base is labelled kene.

For simplicity, we assume that all exporting firms sell abroad a given fraction f of their producton, and that this fraction f (export intensity) is a parameter that is exogenously defined for all firms belonging to the same market (sector, country). In line with our stylized fact 3, the export intensity parameter is arguably higher for firms in the defence industry than in other sectors of the economy. Further, in our simulation exercises, we will set a higher export intensity for enterprises in small open economies than in larger countries, since the former do on average sell a higher share of their turnover in foreign markets than the latter. In future extensions of the model, it would be straightforward to make export intensity an endogenous variable, e.g. determined by each firms’ productivity level. This would reinforce the model’s dynamics, since firms endowed with higher technological capabilities would also have higher productivity levels and hence larger export intensity.

Recall also that the initial price of a new product is set as a function of its quality (see Eq. 5 above), so that the g parameter introduced here simply represents an incremental price adjustment factor that is applied by the firm in each period on the basis of the demand conditions it faces.

We have stopped our simulation runs at period 300 because, as clearly shown in Fig. 2, the model dynamics gets remarkably stable from that period onwards.

This interpretation is reasonable in the light of the literature on firm heterogeneity and international trade (Melitz, 2003). It is however important to emphasize that our model focuses on the export behavior of domestic firms but does not consider explicitly the possibility that foreign firms enter the domestic market after the liberalization process. We only consider this possibility in an implicit manner, i.e. through an increase in domestic enterprises’ success threshold, which is an indirect measure of the higher degree of competition in the domestic market led by liberalization.

It is also important to notice that the results described below in this section do not depend on the specific parameter setting that we have used to calibrate the large- and small-country cases, but are general and hold for different configurations of the parameters that we have experimented with.

This result holds for any given level of human capital (e.g. quality of technical talent) and capital resource endowments. In other words, our model does not consider the possibility that two countries may differ in terms of human or financial capital endowments, given the close similarity of European countries in this respect. The result pointed out here does therefore only depend on country size: ceteris paribus, a small economy will adjust more rapidly to liberalization than a large country due to the more rapid effects that competition and selection mechanisms have in a smaller market.

References

Ahrweiler P, Gilbert N, Pyka A (2011) Agency and structure. A social simulation of knowledge-intensive industries. Comput Math Organ Theory 17:59–76

Almudi I, Fatas-Villafranca F and Izquierdo LR (2012) Industry dynamics, technological regimes and the role of demand, paper presented at the Conference on Governance for a Complex World, Nice, November 2012

Castellacci F (2011) Technology, heterogeneity and international competitiveness: insights from the mainstream and evolutionary economics paradigms, In: Jovanovic M (ed.) International handbook of economic integration. Edward Elgar

Castellacci F (2013) Service firms heterogeneity, international collaborations and export participation, J Ind Compet Trade 1–27

Castellacci F and Fevolden A (2013) Capable companies or changing markets? Explaining the export performance of firms in the defence industry, Defence and Peace Economics. (in press)

Castellacci F, Fevolden A and Lundmark M (2014) How are defence companies responding to EU defence and security market liberalization? A comparative study of Norway and Sweden, J Eur Public Policy, forthcoming

Ciarli T (2012) Structural interactions and long run growth: an application of experimental design to agent based models, Papers on Economics & Evolution 1206

Ciarli T, Lorentz A, Savona M and Valente M (2012) The role of technology, organization, and demand in growth and income distribution, LEM Working Paper 2012/06

Dosi G, Fagiolo G, Roventini A (2010) Schumpeter meeting keynes: a policy-friendly model of endogenous growth and business cycles. J Econ Dyn Control 34:1748–1767

Edwards J (2011) The EU defence and security procurement directive: a step towards affordability?, International Security Programme Paper 2011/05. Chatham House, London

Gilbert N, Ahrweiler P, Pyka A (2007) Learning in innovation networks: some simulation experiments. Phys A 378:100–109

Guay T, Callum R (2002) The transformation and future prospects of Europe’s defence industry. International Affairs 78(4):757–776

Helpman H, Melitz M, Yeaple S (2004) Export versus FDI with heterogeneous firms. Am Econ Rev 94(1):300–316

Klepper S (1996) Entry, exit, growth, and innovation over the product life cycle. Am Econ Rev 86(3):562–583

Lichtenberg FR (1995) Economics of defense R&D. In: Hartley K, Sandler T (eds) Handbook of defense economics, vol 1. Elsevier, Philadelphia

Malerba F, Montobbio F (2003) Exploring factors affecting international technological specialization: the role of knowledge flows and the structure of innovative activity. J Evol Econ 13:411–434

Malerba F, Orsenigo L (1996) Schumpeterian patterns of innovation are technology-specific. Res Policy 25:451–478

Markowski S, Hall P, Wykie R (2010) Defence procurement and industry policy: a small country perspective. Routledge, London

Melitz M (2003) The impact of trade and intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica 71(6):1695–1725

Mowery D (2010) Military R&D and innovation. In: Hall B, Rosenberg N (eds) Handbook of the economics of innovation. Elsevier, Philadelphia

Nelson RR, Winter SG (1982) An evolutionary theory of economic change. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Pavitt K (1984) Sectoral patterns of technical change: towards a taxonomy and a theory. Res Policy 13:343–373

Pyka A, Gilbert N, Ahrweiler P (2007) Simulating knowledge-generation and distribution processes in innovation collaborations and networks. Cybern Systems 38(7):667–693

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: our contribution to the SKIN model class

Appendix: our contribution to the SKIN model class

The model presented in this paper is largely based on the SKIN model developed by Gilbert et al. (2007), Pyka et al. (2007) and Ahrweiler et al. (2011). Our paper applies the SKIN model to a new context—the defence industry—and in doing so it introduces some novel features in the SKIN model framework. The following table points out the new aspects that are introduced in the present paper. All other parts of the model that are not discussed in this table are based on the original version of the SKIN model.

New aspect | Key feature | Specific characteristics |

|---|---|---|

Focus and objectives | We focus on export performance and liberalization, incorporating new features from the firm heterogeneity and international trade literature into the SKIN model | New parameters: (1) export threshold; (2) export intensity New outcome variables: (1) export propensity; (2) export concentration ratio |

Model mechanism | Publicly-funded incremental innovation: successful firms may receive a public grant to finance a new R&D project | New parameters: (1) success threshold; (2) product quality threshold; (3) competence breadth threshold; (4) public subsidy |

Simulation analysis | Analysis of the long-run properties of the model | Statistical analysis of the effects of changes in the main policy parameters on the model’s outcomes, and of the cross-effect of these parameters (2k factorial design) |

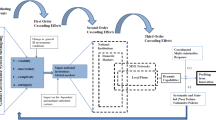

Presentation | A more extended presentation of some of the characteristics of the model | Stylized facts to be reproduced by the model (Sect. 2) Formal presentation of the model (Sect. 3) Diagram with overview of model’s functioning (Fig. 1) |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Blom, M., Castellacci, F. & Fevolden, A. Defence firms facing liberalization: innovation and export in an agent-based model of the defence industry. Comput Math Organ Theory 20, 430–461 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10588-014-9173-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10588-014-9173-6