Abstract

This paper explores the relationship between business experience in cross-sector partnerships (CSPs) and the co-creation of what we refer to as ‘dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation,’ consisting of the four dimensions of (1) sensing, (2) interacting with, (3) learning from and (4) changing based on stakeholders. We argue that the co-creation of dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation is crucial for CSPs to create societal impact, as stakeholder-oriented organizations are more suited to deal with “wicked problems,” i.e., problems that are large, messy, and complex (Rittel and Webber, Policy Sciences 4:155–169, 1973; Waddock, Paper presented at the 3rd international symposium on cross sector social interactions, 2012). By means of a grounded theory approach of inductive research, we collected and interpreted data on four global agri-food companies which have heterogeneous experience in participating in CSPs. The results of this paper highlight that only companies’ capability of interacting with stakeholders continually increases, while their capabilities of sensing, learning from, and changing based on stakeholders first increase and then decrease as companies gain more experience in CSP participation. To a large extent, this can be attributed to the development of corporate strategies on sustainability after a few years of CSP participation, which entails a shift from a reactive to a proactive attitude towards sustainability issues and which may decrease the need or motivation for stakeholder orientation. These findings open up important issues for discussion and for future research on the impact of CSPs in a context of wicked problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction and Research Objectives

One of the key impacts of cross-sector partnerships (CSPs) is the co-creation of resources by participating organizations through processes of engagement, knowledge exchange, and inter-organizational learning (Austin and Seitanidi 2012). Starting with diverse resources and capabilities, business and non-business organizations in CSPs can generate collaborative advantage and shared value (Teegen et al. 2004; Glasbergen 2010; Porter and Kramer 2011) by gaining and sharing information, knowledge, and skills (Austin 2000; Waddell 2000; Selsky and Parker 2005). This ‘win-win’ potential indicates that collaboration is likely to emerge when each partner can receive access to resources and capabilities that they would otherwise not have (Austin 2000; Waddell 2000; Rondinelli and London 2003).

Yet, to evolve and survive in a world increasingly characterized by wicked problems (Dentoni et al. 2012a; Waddock 2012), organizations participating in CSPs require more than just resources and capabilities. Wicked problems, such as poverty, climate change, environmental degradation or food insecurity, have no closed-form definition, emerge from complex systems in which cause and effect relationships are either unknown or highly uncertain, and have multiple stakeholders with strongly held and conflicting values related to the problem (Rittel and Webber 1973; Weber and Khademian 2008). Wicked problems require organizations to learn how to anticipate, react, harmonize, or somehow address the requests and concerns of a wide range of stakeholders (Gray 1989; Glasbergen 2007; Kolk et al. 2008; Waddock 2012). In this context, organizations need to be more oriented towards stakeholders, thus to develop a specific type of dynamic capabilities (Teece et al. 1997) that allow them to respond effectively to the concerns of multiple societal groups and thus address wicked problems. Given this organizational challenge, this study explores the impact of CSPs on the dynamic capabilities of its business participants that are needed for dealing with wicked problems. To this purpose, we introduce the concept of dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation to describe those dynamic capabilities which allow organizations to adapt to changing environments by effectively (1) sensing, (2) interacting with, (3) learning from, and (4) changing based on stakeholders. The impact of CSPs on the co-creation of dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation is relevant not only for the participating organizations, but for society as a whole, as CSPs increasingly play a governance role in society (Teegen et al. 2004). CSPs that stimulate dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation become effective sense-making devices (Selsky and Parker 2010) to understand the changing nature of wicked problems and to gain awareness on the consequences of partners’ actions on society.

To interpret the impact of CSPs on the co-creation of dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation, this study follows a grounded theory approach of inductive research (Glaser and Strauss 1967; Suddaby 2006). We chose this method given the lack of a substantive theory on the co-creation of dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation through CSPs. This gap corresponds to a general lack of analyses seeking to assess the impact of CSPs (Lund-Thomsen 2009; Seitanidi 2010; Van Tulder 2012), despite their rapid proliferation in practice. We provide empirical evidence on the in-depth studies of four global agri-food companies (Unilever, Friesland Campina, Sara Lee and Heinz) that developed a “portfolio of CSPs” (Van Tulder 2012) over the last 10 years. We selected the agri-food sector as empirical field of research because the tensions between land, natural resources, feed, food, and energy are recognized to be urgent wicked problems (Batie 2008). Moreover, CSPs in this sector have increased swiftly in the last decade (Dentoni and Peterson 2011).

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. “Methods: A Grounded Theory Approach” section introduces and justifies the grounded theory approach taken. “Theoretical Background” section considers partnerships from a resource/capability-based view and from a stakeholder theory perspective. Based on these two views, we develop the concept of dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation as a potential impact of CSPs. “Key Background Information” section gives an overview of the companies studied and their engagement in CSPs. We present and synthesize our results in testable propositions in “The Impact of Cross-Sector Partnerships on Dynamic Capabilities for Stakeholder Orientation” section. “Discussion” section explores the managerial and policy implications of the findings, while “Conclusion” section concludes.

Methods: A Grounded Theory Approach

Consistent with the pursued grounded theory approach (Glaser and Strauss 1967; Suddaby 2006), this study took place in four different stages between 2009 and 2012. The first stages were broad and unfocused to identify the points of originality and relevance of the observed phenomenon, while the following stages made the data collection and analysis more focused and systematic (Strauss and Corbin 1994).

First, in 2009 and early 2010, we joined discussion sessions during five international agribusiness conferences and conducted 34 interviews with business managers, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and academics who participated in CSPs in the agri-food sector, specifically the Sustainable Agriculture Initiative (SAI) Platform, TransForum, The Roundtable on Responsible Soy, The Carbon Disclosure Project, and the Dutch Sustainable Trade Initiative (IDH). At this stage, we realized that the actors involved were motivated to establish CSPs not only to share resources, co-create operational capabilities, and solve specific wicked problems as they explicitly claimed, but also to develop a capacity to understand and learn systematically from their stakeholders, considering that many of them were out of their network beforehand.

Second, between 2010 and early 2011, we undertook a systematic screening of the CSPs created or joined by the 50 largest agri-food multi-national companies (MNCs; Dentoni and Peterson 2011). We chose these MNCs because of the large amount of data available through web electronic sources compared to smaller firms, and the rapid proliferation of CSPs in the agri-food sector compared to other sectors. We collected data from reports published by the MNCs, their respective CSPs, and their private and public partners. Data collected involved the number, type, and role of stakeholders participating in each partnership, the year of creation, the goal and focus area of intervention, and the governance structure of CSPs. Through this stage, we obtained an overview of the universe of CSPs in the global agri-food sector: 22 out of the 50 largest MNCs were involved in 38 partnerships (Dentoni and Peterson 2011). We were also able to create a broad picture of the different levels of experience that these 22 MNCs had in participating in CSPs. Importantly, we recognized that some MNCs had longer experience in participating in CSPs than others. This allowed making a purposive sample selection (Yin 2009) in the following step of the study.

Third, we selected the following four MNCs, which exhibited heterogeneous levels of experience in CSPs, for further study: Unilever has the longest experience, Friesland Campina and Sara Lee have a medium level of experience, while Heinz has the shortest experience. “Experience in CSPs” was measured qualitatively as a combination of the number of years from the first CSP participation, the number of CSPs joined, and the degree of CSP participation (“leading” founder (or co-founder) or “follower”; see “Key Background Information” section). Between 2011 and early 2012, we conducted 25 interviews with managers of the four MNCs (from sustainability/CSR, research and development, procurement and/or marketing departments) and with the representatives of their partnering organizations within CSPs (especially NGO managers; see “Appendix 1” section for detailed information). The interviews were semi-structured and focused on understanding the extent to which the MNCs are able to sense, interact with, learn from, and change based on stakeholders, and how the process of developing such capabilities took place. We used indirect questioning techniques to learn from the interviewees while attempting to minimize social desirability bias (Fisher 1993). In particular, we asked the interviewees to describe the sustainability initiatives undertaken by the four MNCs with stakeholders over time, both within and outside of CSPs. After the interviews, we triangulated our interpretations based on the written interview records.

Fourth, from late 2011 to early 2012, we undertook a systematic screening of the sustainability/CSR reports produced by the four MNCs to triangulate the primary data collected through interviews in the previous research stages. In particular, we collected secondary data from sustainability/CSR reports produced in the first year in which companies joined or created a CSP (between 2002 for Unilever and 2007 for Friesland Campina) and in the last year of reporting available (2010). We then developed exploratory measures, or proxies, for the emerging dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation to capture the change in sensing, interacting, learning, and changing based on stakeholders through word counting and semantics (Duriau et al. 2007). We developed a specific set of measures for each type of capability (“Appendix 2” section). For example, the measures used for sensing stakeholders relate to (i) breadth of the stakeholder portfolio (S1), (ii) relevance of stakeholders (S2), (iii) relevance of stakeholders related to the impact of a corporate sustainability initiative or strategy (S3), and (iv) the assessment of sensing capabilities by stakeholders operating outside the specific supply chain (S4). Similarly, we captured the remaining three capabilities by developing three–five measures each.

Theoretical Background

Partnerships and the Co-creation of Resources and Capabilities

From a resource-based view, a key driving force for organizations entering into CSPs is the prospect of accessing and co-creating new resources and capabilities (Austin 2000; Waddell 2000; Rondinelli and London 2003; Selsky and Parker 2005). Resources are strengths, advantages, or assets, including technical know-how, management skills, human capital, and reputation, which organizations can use to conceive of and implement their strategies (Barney 1991; Penrose 1959; Wernerfelt 1984). Among these resources, capabilities describe the ability of adapting, integrating, and reconfiguring internal and external organizational skills, resources, and functional competences (Teece et al. 1997). Accordingly, organizations are motivated to collaborate in order to develop and gain access to new external resources, particularly those that are scarce and inimitable, such as tacit knowledge-related and competence-related resources (Dierickx and Cool 1989; Barney 1991; Peteraf 1993; Gulati 1999; Prahalad and Ramaswamy 2004). However, contrary to traditional business alliances that are characterized by low organizational diversity and high task specificity, CSPs include actors that have fundamentally different core logics, operating principles, and goals (Waddell 2002). This diversity makes collaboration more vulnerable to tensions and conflict unless trust is created (Le Ber and Branzei 2010a; Glasbergen 2011). At the same time, it creates high incentives for collaboration due to the heterogeneous resources and capabilities of partners, which can, if they are shared, produce collaborative advantage and create impact which no organization could have created on its own (Huxham 1993). Studies have distinguished between a variety of resources and capabilities among CSP participants, among which the provision of financial capital, market knowledge, and management expertise by business participants, and the provision of issue knowledge, legitimacy, and community relationships by NGOs are most frequently mentioned in the literature (Waddell 2002; Dahan et al. 2010). By participating in CSPs, businesses can enhance reputation, access local knowledge, and increase their corporate social responsibility performance, while NGOs can receive access to technical, organizational, and financial resources (Arts 2002; Teegen et al. 2004).

Relative to this co-creation of “operational capabilities” (Winter 2003), dynamic capabilities represent a form of “double-loop learning” or “learning how to learn” (Argyris 1977). They refer to “the ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments” (Teece et al. 1997, p. 516). Dynamic capabilities are considered critical for sustainable competitive advantage in the face of rapid technological change and the uncertain nature of future competition and markets (Teece et al. 1997; Helfat et al. 2007). Yet, addressing wicked problems, including various sustainability challenges, and responding to stakeholders’ concerns changes the nature of dynamic capabilities needed by companies (Verona and Zollo 2011; Dentoni et al. 2012a) for two major reasons. First, the notion of sustainability requires the integration of economic, social, and environmental outcomes, whereas the outcomes of dynamic capabilities are traditionally defined in terms of economic efficiency/effectiveness. Second, traditional dynamic capabilities may not attend to key issues required to address sustainability challenges, including the nature of the core business activity, firm values, and strategic intent (Teece 2007). This suggests that the ability of CSPs to create impact in the form of co-creating dynamic capabilities depends on how organizations engage with their stakeholders.

Partnerships and Stakeholder Theory

The strategic value of collaboration is also recognized in stakeholder theory, which views organizations to be at the center of a network of stakeholders who can affect or are affected by the achievement of the organization’s objectives (Freeman 2010). Stakeholders are defined according to their relation with the focal organization, which is usually a company (Clarkson 1995). The challenge for companies is then to accommodate the claims of stakeholders, recognizing that the long-term sustainability of their business depends on co-operative relations with these stakeholders (Freeman 2010; Donaldson and Preston 1995). Starting from the 1990s, the literature has debated on how firms should identify stakeholders as well as manage and respond to their claims (Laplume et al. 2008). According to Mitchell et al. (1997), the question of whether or not stakeholders deserve attention depends on their legitimacy, the urgency of their claims, and their (potentially threatening) power. From this perspective, developing partnerships is a vehicle for businesses to be “more socially responsible to address stakeholder demands and develop or sustain a competitive advantage” (Selsky and Parker 2005, p. 852). Yet, scholars recognize that firms may identify different stakeholders depending on their culture (Jones et al. 2007), their own life cycle (Fineman and Clarke 1996), and the industry context (Jawahar and McLaughlin 2001). Moreover, they may engage in different ways with stakeholders depending on their motivation and capacity (Lawrence 2002) and their leadership (Maak 2007).

Despite this advancement of stakeholder theory, only in the last decade have scholars started focusing on the organizational capabilities that make stakeholder orientation, identification, and engagement more effective (Ferrell et al. 2010; Verona and Zollo 2011). Cross-sector collaboration presupposes that organizations are “dedicated to learning about and addressing stakeholder issues” (Ferrell et al. 2010, p. 95) and oriented towards two-way communication and consensual decision-making (Ansell and Gash 2008). Such stakeholder orientation is an organizational culture and behavior inducing organizations to be continuously aware of and proactively act on issues that are of concern to one or more stakeholders (Maignan and Ferrell 2004; Ferrell et al. 2010). In the context of wicked problems, stakeholder orientation is critical, as organizations are forced to transcend their traditional relationship boundaries and interact with multiple stakeholders that may have differing goals and cultures (Batie 2008). This entails moving from viewing stakeholders as opponents to valuing them as complements (Freeman 2010), which, in turn, makes it easier to be structurally oriented towards each other’s needs, to learn from each other and to change based on jointly agreed goals (Selsky and Parker 2010). Thus, by interacting with multiple stakeholders and tackling wicked problems, organizations mitigate and share risks, which, in the long run, increases their chances of survival (Clarkson 1995; Freeman 2010). Particularly with regard to managing wicked problems, companies increasingly realize that they need to understand, interact and, at least to some extent, adapt to the pressures of stakeholders (Ferrell et al. 2010; Hult 2011). Thus, stakeholder orientation is becoming an essential dynamic capability (Clarke and Roome 1999; Hult 2011) rather than an optional managerial attitude (Berman et al. 1999).

Towards the Co-creation of Dynamic Capabilities for Stakeholder Orientation

The argument that CSPs impact on the co-creation of resources and capabilities as well as on the relationships between organizations and their stakeholders implies that the partners themselves tend to be beneficiaries of partnerships. Such a concentration of impact for the participating organizations in CSP is not surprising, considering the amount of time and resources invested in partnerships (Biermann et al. 2007). To systematize the analysis of the impact of CSPs on the organizational level, this study introduces the concept of dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation, which help organizations manage wicked problems by responding effectively to multiple stakeholders’ concerns (Verona and Zollo 2011).

The basic premise is that over time CSPs can influence the ability of organizations to react, anticipate, and harmonize the pressures of multiple stakeholders (Vurro et al. 2010; Waddock 2012) through organizational learning and relationship building (Seitanidi and Ryan 2007). From a business perspective, the ability of a firm to successfully partner with an NGO or with other cross-sector stakeholders may itself constitute a dynamic capability that can lead to competitive advantage (Dahan et al. 2010). Such capabilities do not reside in individual participants or organizations themselves, but rather depend on an array of linkages that they have with other actors in the system, and especially on their approach to participation (Robinson and Berkes 2011). This suggests that such dynamic capabilities are the result of interconnected organizations and actors, whose linkages facilitate social learning and co-creation of knowledge (Armitage et al. 2011). In this way, dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation can be classified as higher order dynamic capabilities that are difficult to imitate and have the potential to lead to competitive advantage.

Based on the insights from the theoretical perspectives introduced above and the empirical evidence from the interviews, this study identifies four dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation: sensing stakeholders, interacting with stakeholders, learning from stakeholders, and changing based on stakeholders (hereby synthesized as SILC, see Table 1).

Sensing stakeholders within CSPs is important due to the differences in mission and core logics as well as the historical aversion between partners (Austin 2000; Arts 2002). These can create conflict and distrust between partners that may constrict the formation and implementation of a partnership (Rondinelli and London 2003). Outside of CSPs, sensing stakeholders may be particularly challenging and represents a distinctive asset in a context of wicked problems, since the societal groups affected by the issues tackled within CSPs may swiftly change, making them difficult to identify (Waddock 2012).

Similar to “alliance capability” (Huxham 1993), interacting with stakeholders represents the capacity and readiness of an organization to engage with stakeholders based on reciprocal exchange. Austin (2000) suggests that partnerships require a high level of interaction in order to create value for their participants as well as society at large. Accordingly, success or failure of partnerships to a great extent depends on how partners frame their interactions, appreciate differing perspectives (Le Ber and Branzei 2010b), and learn how to interact in a constructive manner (Roloff 2008). Especially in a context of wicked problems, the vastly different cultures, values, and goals among stakeholders within and outside CSPs create major interaction challenges which demand heightened capabilities in negotiation, communication, and reciprocal understanding.

The process of interaction is crucial for mutual learning and co-production of knowledge (Robinson and Berkes 2011). Learning from stakeholders may result from understanding and finding different approaches to the same challenges, demanding an iterative process of exchanging and combining the knowledge, experience, and competencies of the actors involved (Murphy et al. 2012). However, learning does not only concern the wicked problem which the overall partnership seeks to address, it also feeds back into the participating organizations who learn “about themselves as organizational and sectoral entities” (Selsky and Parker 2010, p. 32).

Engaging with partners through problem sharing purposefully aims at co-designing and implementing innovative solutions to address wicked problems (Murphy et al. 2012). This includes internal changes, such as altering organizational structures, and externally oriented changes, such as co-developing product and process innovations. Changing based on stakeholders is strongly correlated with improved relationships, i.e., sensing and interacting with stakeholders, and the social learning processes emanating from these (Mandarano and Paulsen 2011). Seitanidi et al. (2010) suggest that the previous history of interactions with stakeholders provides an indication of the transformative potential of organizations. In other words, organizations that lack collaboration experience may be unable to articulate their interests and competencies vis-à-vis the strategic approach of other actors, which may make it difficult to develop the transformational capacity required to promote change in the partner organizations.

Key Background Information

Cross-Sector Partnerships in the Agri-food Sector

Since 2001, 22 of the world’s 50 largest MNCs in the agri-food sector have formed and/or joined CSPs with one or multiple heterogeneous stakeholders, including NGOs, governments, and knowledge institutes (Dentoni and Peterson 2011). Within this growing trend of CSP formation, MNCs have taken different approaches of engaging with stakeholders (Dentoni and Peterson 2011). The largest MNCs, such as Nestlé, PepsiCo, Kraft, and Unilever—which each own a portfolio of brands diversified into a number of food sub-sectors—participate in a variety of partnerships covering multiple food sectors with a broader focus on both environmental and social sustainability issues (Dentoni and Peterson 2011). Less diversified and relatively smaller MNCs, such as Bunge, Ferrero, and Friesland Campina, focus mainly on CSPs within a particular sector (e.g., cocoa, palm oil, cashew, or coffee) which correspond more closely to their core strategy. Next to their participation in CSPs, over time several MNCs have codified a strategic intent for their sustainability activities (such as Nestlé’s “Shared Value Creation” model) that strictly relates to their core business strategy, and have started reporting through recently developed environmental and/or social standards (UN Global Compact, the Global Reporting Initiative, and the Carbon Footprint Disclosure).

Four Companies: Cross-Sector Partnerships and Strategic Intent

Unilever: Long Experience in Cross-Sector Partnerships

With Anglo-Dutch origins, Unilever is the world’s second largest MNC manufacturing food, with a portfolio that includes more than 400 food and non-food products and brands sold in more than 180 countries. Unilever is continually broadening its portfolio by expanding existing categories into new geographies or via “bolt on” acquisitions that help to build presence, either in more countries or at a wider range of price points.

Of the four MNCs studied, Unilever has the longest history of CSP participation, starting in 1996 with the Marine Stewardship Council. Since then the company has co-founded 9 CSPs and joined another 11 CSPs (Table 2). All these partnerships relate to strategic resources used in Unilever’s core business, such as water, fish, cocoa, sugar, tea, soy, and palm oil. In 2010, Unilever launched the “Sustainable Living Plan” as a commitment to “a ten year journey towards sustainable growth.” The Plan comprises three main pillars: (1) “improving health and well-being,” which was designed with internal and external behavioral change experts and relies on benchmarks against a range of national dietary recommendations, (2) “reducing environmental impact,” where the most significant environmental impacts of products are measured in terms of their relevance to Unilever, its stakeholders, and society, and (3) “enhancing livelihoods,” including cooperation with suppliers to follow the guidelines from Unilever’s Sustainable Agriculture Code. Suppliers are measured through certification and self-verification.

Friesland Campina: Medium Experience in Cross-Sector Partnerships

Friesland Campina is a multi-national dairy company with Dutch origins which is wholly owned by a dairy co-operative comprising 14,800 member dairy farms in the Netherlands, Germany, and Belgium. Its products are sold in more than 100 countries across Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Since 2003, Friesland Campina has been involved in seven CSPs. The company co-founded two CSPs related to its core business (dairy) and joined five CSPs in sectors related to its key ingredients (e.g., soy and palm oil; Table 2). Between 2008 and 2010, Friesland Campina designed a new overall strategy called “Route 2020,” which integrates its core strategy with activities related to sustainability. Through Route 2020, the company aims to (1) grow by offering a wider range of dairy products, increasing its geographical presence, and shifting to more specialized ingredients in liaison with clients, (2) valorize milk by enhancing its natural qualities, and (3) achieve climate neutral effects of their foreseen growth by improving the energy efficiency of their member dairy farmers and chain partners, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and stimulating the production of sustainable energy on dairy farms.

Sara Lee: Medium Experience in Cross-Sector Partnerships

Sara Lee Corporation is a global consumer-goods company based in Illinois, USA. It has operations in more than 40 countries and sells its products in over 180 nations worldwide. Its largest customer is Wal-Mart Stores (WMT), responsible for 15 % of its total sales.

Sara Lee has been involved in CSPs since 2004, particularly in partnerships dealing with specific commodities, such as coffee and tea (Table 2). In 2006, it created an internal sustainable working team with the goal of ensuring that sustainability activities are aligned with its global business strategy. The team is a network of members from all business units and corporate functions under the leadership of the Vice President. The implementation of sustainability into business strategies is customized for each business segment and market. In 2009, business-specific environmental goals were set at a facility level for conservation of energy and water and reduction of waste with the baseline of 2005. The target year for achieving the goals is 2012.

Heinz: Shorter Experience in Cross-Sector Partnerships

Headquartered in Pittsburgh (Pennsylvania, USA), Heinz is a global food processing company which markets its products in more than 200 countries and territories worldwide.

Heinz joined two CSPs in 2005 and 2007 and later co-created two CSPs in the cocoa sector, which represents one of its core businesses together with tomato (Table 2). Related to, but not included in its core strategy, Heinz codified a “Sustainability Process” to provide a customizable sustainability program for each business unit under a business model embodying Heinz’s strategy. Set up unilaterally in 2005 with the target year of 2015, these sustainability goals are related to reducing energy consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, solid waste, water consumption, and total packaging material; increasing renewable energy and employee engagement through an awareness and voluntary personal sustainability campaign; improving tomato agriculture by reducing water and carbon footprint; and increasing tomato crop yields through the use of hybrid tomato seeds.

The Impact of Cross-Sector Partnerships on Dynamic Capabilities for Stakeholder Orientation

CSP Experience and Sensing Stakeholders

Empirical evidence indicates that, although starting from different initial levels, in the years after founding the first CSPs companies’ capability of sensing stakeholders both within and outside the partnerships increased. Yet, with growing experience in CSP participation, the capability of the four MNCs to sense stakeholders outside existing CSPs decreased (Table 3). Since experience in CSP is measured as a combination of qualitative variables, the “early” rather than “later” level of experience (as in Table 3 and following) is approximate and subject to interpretation. Unilever’s “early” stage is considered to be 10 years (1996–2006) as the company took a long time to participate in other CSPs after founding the first one. On the other hand, Heinz’s “later” stage is restricted to only 2 years (2010–2012) because the company has the shortest experience with CSPs. This pattern of increasing and then decreasing sensing capabilities across the four companies leads to the following proposition:

P1

Increased experience in CSPs has an inverted U-shaped effect on companies’ capability of sensing stakeholders over time. That is, as companies become more experienced in CSP participation, their capability of sensing stakeholders first increases and then decreases.

A key factor that drives such an inverted U-shaped effect seems to be the development of a corporate strategy on sustainability. Unilever started developing its Sustainable Living Plan in 2007 and launched it in 2010. Friesland Campina did so with their Route 2020 strategy, published in 2010. Sara Lee and Heinz developed specific targets on greenhouse gas emissions and certified procurement in the late 2000s. Over time, this trend of increased strategic focus made companies more proactive in sensing and understanding established partners within CSPs and less reactive to the demands of stakeholders outside of CSPs (Table 3). It could be argued that this could be interpreted as a decrease in the motivation rather than a decrease of a dynamic capability of sensing stakeholders. Yet, the adoption of a corporate strategy pre-defining scope, goals, and partners limits companies’ opportunity of re-deploying organizational resources and skills to understand and react to stakeholders outside CSPs. Therefore, while developing a corporate strategy during early stages of CSP experience is a voluntary corporate action, the decreased capability of sensing stakeholders over time seems to be an involuntary side effect of developing such a strategy.

Relative to the inverted U-shaped effect of CSP experience on firms’ sensing capability, two notes of caution are needed. First, the proposition indicates a pattern of change over time, but the initial and final levels of sensing capabilities vary significantly across companies. Some companies demonstrated a higher capability of sensing stakeholders than other companies. This might depend on factors such as resources available to the firms, history, culture, leadership, and the location of their headquarters. Second, after the described decrease, firms’ sensing capabilities may increase again if firms realize the risks of not sensing stakeholders outside of CSPs. For instance, sensing capabilities may increase again as CSP experience further develops or as pressure on companies grows, either from stakeholders outside of CSPs or from internal stakeholders that decide (or threaten) to exit CSPs.

CSP Experience and Interacting with Stakeholders

As described in Table 4, due to growing CSP experience, the four companies continually increased their capability of interacting with stakeholders over time. This leads to the following proposition:

P2

Increased experience in CSPs has a positive effect on companies’ capability of interacting with stakeholders over time. That is, as companies become more experienced in CSP participation, their capability of interacting with stakeholders continually increases.

The increased capability of interacting with stakeholders is not surprising, neither from a managerial nor an institutional standpoint. Interviews with company managers confirmed a learning curve for the organizations on how to establish interactions and collaboration with new stakeholders outside their supply chain, especially NGOs and non-business organizations. After the first experience of engaging with new stakeholders in CSPs, managers sought further opportunities to collaborate—either with the same partners or with new stakeholders having a similar background and culture—as they expected to become more efficient in taking joint decisions. From an institutional point of view, once they had joined one or more new CSPs with stakeholders, the companies could efficiently use the same CSP governance structure to extend the interaction with existing stakeholders, either discussing new sustainability issues or the same issues in new sectors or geographical areas, or establish ties with new stakeholders within the frame of their emerging corporate sustainability strategies.

Similar to the stakeholder sensing capabilities, also the capability of interacting with stakeholders varied across the four companies. Over time, some companies led discussions in CSPs on sustainability problems that were “very wicked,” that is, global, particularly messy, urgent, and with a larger number of actors’ interests to orchestrate (Levin et al. 2012). These interactions required an intense learning process, as the aspects of the problems to be discussed required more time, resources, and participation. Other companies chose not to expand their stakeholder interaction, but rather intensify the engagement with a smaller set of stakeholders, mainly for the adoption and implementation of specific social or environmental standards.

CSP Experience and Learning from Stakeholders

Empirical evidence shows that the relationship between CSP experience and the capability of learning from stakeholders follows an inverted U-shaped pattern similar to stakeholder sensing in P1 (Table 5). Initially, during the development of the first CSPs, companies rapidly “learned how to learn” from stakeholders. However, as their experience in CSPs increases over time, their capability of learning from stakeholders seemed to decrease. Data suggest that three out of the four companies (Unilever, Friesland Campina, and Sara Lee) mainly kept focusing on learning from stakeholders within the established CSPs, but not from new stakeholders outside the early founded CSPs. Heinz has a shorter experience with CSPs and still seems to be in the growing stage of learning from stakeholders (Table 5). This leads to the following proposition:

P3

Increased experience in CSPs has an inverted U-shaped effect on companies’ capability of learning from stakeholders over time. That is, as companies gain more experience in participating in CSPs over time, their capability of learning from stakeholders first increases and then decreases.

Similar to sensing, also the inverted U-shaped effect of CSP experience on learning from stakeholders seems to be influenced by the development of a corporate strategy on sustainability. While all cases appear to follow the trend of first increased and then decreased learning capability, a distinction can be made between different types of learning. Companies that interacted with a large set of stakeholders on “very wicked” sustainability issues co-created broader knowledge to understand which practices are acceptable for a large number of stakeholders participating in the discussion. This can be considered a type of social learning which deals with problem framing and re-framing based on joint information sharing and knowledge development. We see that Unilever and Friesland Campina initially engaged in this type of learning. On the other hand, companies that built relationships with only few stakeholders based on a specific topic focused on technical learning to understand measurement and assessment issues, and establish indicators and criteria. Sara Lee and Heinz, but also Unilever and Friesland Campina in their later stages of CSP experience, appear to follow this strategy of technical learning.

CSP Experience and Changing Based on Stakeholders

As the experience with CSPs increases, the capability of the four companies to change based on stakeholders first seemed to increase and then to decrease (Table 6). In other words, the capability of changing based on stakeholders follows the same pattern as sensing and learning from stakeholders. During their early experience with CSPs, the companies studied featured a high ability to implement organizational changes based on their engagement with stakeholders. With growing experience, however, the companies seemed to significantly slow down and “merely” follow through with the changes agreed upon in the earlier years of their CSP participation (Table 6). This does not imply that the companies stagnated, but rather that any type of new change appeared to be based on internal initiatives instead of stakeholders. Only Heinz still seems to be in the stage of significant change given its shorter CSP experience (Table 6). This leads to the following proposition:

P4

Increased experience in CSPs has an inverted U-shaped effect on companies’ capability of changing based on stakeholders over time. That is, as companies become more experienced in CSP participation, their capability of changing based on stakeholders first increases and then decreases.

Similar to sensing and learning from stakeholders, also the capability of changing based on stakeholders is influenced by the development of a corporate sustainability strategy. Based on their CSP experience and an earlier period of reaction to stakeholder pressures, the companies became proactive in addressing sustainability issues, either on a broad range of issues or in a specific domain. In other words, a company’s corporate strategy on sustainability has become more important as a driver for organizational change than the agenda of stakeholders.

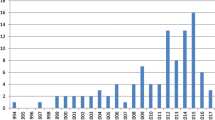

Discussion

The findings from our four cases suggest that the experience of companies in participating in CSPs has a significant effect on their dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation. With regard to companies’ ability to sense, learn from, and change based on stakeholders, increased experience in CSPs appears to have an inversed U-shaped effect, indicating first a positive (increasing) and later on a declining effect of CSPs. We do not propose that this decline in capabilities brings back companies to the (low) capability levels prior to the partnership experiences, as companies retain and reutilize their capabilities to some extent through continuous involvement in CSPs. However, companies are not able to uphold the steep increase in capabilities which results from initial experiences in CSPs. Only the capability of companies to interact with stakeholders appears to continually increase as they become more versed in participating in CSPs. The resulting four propositions described above are visualized in Fig. 1 and synthesized as a theoretical framework in Fig. 2.

Relationship between CSP experience and dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation. Source own elaboration based on collected data. Explanation: X level of CSP experience, Y dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation, S sensing stakeholders, I interacting with stakeholders, L learning from stakeholders, C changing based on stakeholders

Our interpretation is that the underlying cause of such an inverted U-shaped effect with regard to sensing, learning, and changing is the development of a corporate sustainability strategy. During the early stages of CSP participation, companies are more reactive and thus more attentive to their external environment in order to identify issues and partners from a broad set of stakeholders. After identifying a number of key stakeholders as partners, companies elaborate strategies that take into account (some of) the sustainability principles co-developed with their new partners in CSPs. As they move towards the implementation phase and design programs to reach their newly established goals, companies limit their search for new stakeholders and also their openness to learn from new stakeholders, which then affects their ability to change based on new stakeholders.

Two points of discussion arise from this interpretation of findings. First, what are the benefits and risks, both for companies and for society, if companies develop sustainability strategies that decrease their dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation? From a company perspective, the development of a corporate strategy on sustainability may serve as isomorphic adaptation to the expectations of external stakeholders, as strategic manipulation of these expectations, and as a means for moral reasoning (Scherer et al. 2013). This may not only increase the legitimacy of companies in complex environments (Scherer et al. 2013), at least temporarily, but can also decrease transaction costs, as companies need to invest less resources to search and coordinate with new stakeholders. Moreover, companies with a dedicated sustainability strategy may strengthen their distinctive value proposition to customers in order to create competitive advantage that may be “more sustainable than conventional and cost and quality improvements” (Porter and Kramer 2011, p. 16). At the same time, decreasing dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation pose longer term risks for the organization and society. Companies risk becoming unperceptive, disengaged, and unreactive to the pressures of stakeholders outside of CSPs (Hospes et al. 2012), and therefore risk their sustainability strategies to be delegitimized (Hult 2011). Ultimately, low capabilities of understanding and reacting to stakeholders that were not considered in their strategy development may compromise companies’ growth and even survival (Freeman 2010). From a societal standpoint, companies that are oriented only towards a restricted set of stakeholders in CSPs do not tackle wicked problems (Dentoni et al. 2012b; Waddock 2012). This could compromise the positive impact of CSPs on under-represented company stakeholders (Bitzer 2012) and make sustainability problems even more wicked (Hospes et al. 2012; Levin et al. 2012).

Second, how can companies and their stakeholders prevent the risk of decreasing dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation to enhance the positive impact of CSPs? Four organizational issues stand out from a company perspective. First, research suggests that the capability to form and maintain inter-organizational alliances requires the institutionalization of codification processes to accumulate know-how across the organization (Kale and Singh 2009). Tools and templates to assist managers in identifying and assessing opportunities for collaboration play a critical role in facilitating replication and transfer of capabilities within an organization (Kale and Singh 2009). Second, feedback mechanisms at different levels allow organizations to build reflective capacity and maintain a “reflective discourse” on organizational practices vis-à-vis their external stakeholders and CSP partners (Scherer et al. 2013). Third, traditional elements of organizational stability, such as identity, need to be paired with organizational flexibility (Schreyögg and Sydow 2010), especially considering that also the partner organizations and the collaborations with them continuously change (Huxham 1993). Finally, strengthening communication and engagement between managers involved in CSPs and the “regular” internal organization helps improve the organization’s orientation towards its partners, leverage relevant internal capabilities, and identify and implement new partnering opportunities.

Companies’ stakeholders, including CSP facilitators, also have a role to play in preventing declining dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation. First, stakeholders within CSPs have the opportunity of constantly reassessing their organizational fit vis-à-vis their corporate partners, as well as of strategically shifting between supporter and opponent roles depending on companies’ behavior. This holds particularly for NGOs due to their flexibility in applying both strategies of insiders and outsiders (Teegen et al. 2004). When sensing that companies do not adequately address sustainability problems and stakeholders outside of CSPs, NGOs can change their engagement strategy and move from insiders to outsiders of CSPs to provoke renewed attention by companies (Pesqueira and Verburg 2012). Second, stakeholders outside of CSPs, such as policy-makers and academics, can play a critical role in facilitating the interactions of CSPs with a wider societal audience and with other CSPs that operate in a similar space (Hospes et al. 2012). This could help increase awareness and harness the parallel development of different initiatives which may ultimately raise the benchmark for corporation’s engagement in CSPs.

Conclusion

Over the last 10 years, CSPs have emerged as novel organizational forms that allow members to co-create resources and capabilities in order to move towards their established sustainability goals (Austin 2000; Rondinelli and London 2003). Yet, in a context of wicked problems faced by CSPs, structuring sustainability challenges and defining joint goals are complex, if not impossible, and require coordination with a broad, often undefined set of stakeholders (Waddock 2012). To deal with wicked problems, both participants in CSPs and society would benefit from organizations that are able to re-deploy their resources and capabilities based on a continuous process of stakeholder identification and engagement (Ferrell et al. 2010; Freeman 2010; Hult 2011). In this paper, we first introduced the concept of dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation to describe organizations’ ability to sense their stakeholders, interact with them, learn from them, and change accordingly. Second, we explored the impact of companies’ experience in CSPs on the creation of dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation together with (thus, “co-creation”) other CSP members. Findings from four companies selected based on their heterogeneous levels of CSP experience suggest that companies developed their dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation in the early stages of their CSP experience and then decreased at a later stage. We interpret this inverted U-shaped effect of CSPs on the co-creation of dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation as the effect of companies developing corporate strategies on sustainability after a few years (between 5 and 10) of participation in CSPs. On the basis of this interpretation, we discussed the implications of the impact of CSPs on companies’ dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation over time. On one hand, organizations and society may benefit from companies that have proactive strategies rather than reactive ad hoc initiative to address sustainability issues. On the other hand, in a context of wicked problems, organizations and society may encounter risks if companies and their cross-sector partners do not continue sensing, engaging, learning, and changing based on stakeholders outside of CSPs.

The results from this study are exploratory in nature and subject to multiple interpretations. Specifically, individual factors (such as leadership styles and CEO commitment), organizational factors (such as the history, culture, and legal structure of corporations), and inter-organizational factors (for instance, goal deviation and power differences within CSPs, the civil society base in the countries where the firm operates, the style of stakeholder pressure, and its change over time) may also shape companies’ dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation in interaction with or in substitution to the CSP experience. These factors are not analyzed in this study and future research would expand knowledge by considering them. Moreover, to make these findings more general, future research may test the proposed framework with other companies within or outside the agri-food sector, or even with other organizations participating in CSPs (NGOs, MNCs’ chain partners, governments, knowledge institutions). A challenge for testing the proposed framework with a deductive method is to develop measures of dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation that go beyond asking direct questions to managers (Berman et al. 1999; Yau et al. 2007). In this direction, Cuppen (2012) developed a quasi-experimental methodology to test the outcomes of stakeholder interaction. A similar methodology could be used to test for other dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation.

While this study focused on the effect of CSPs on corporate capabilities, a question that remains open is how CSPs impact the dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation of non-business partners. Do NGOs, academics, policy-makers, and other civil society organizations enhance their ability to sense, interact, learn, and change based on stakeholders as they participate in CSPs? Or do we perhaps see a similar pattern as with the four companies studied in this article? Analyzing whether the observed inverted U-shaped effect on the capabilities of sensing, learning, and changing is indeed a “corporate” phenomenon or a general impact of CSPs would hence be an interesting avenue for further research.

Finally, the implications of our results on the impact of CSPs on dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation require a normative discussion. From the point of view of CSP facilitators, company managers, and stakeholders, our results beg the question if dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation are ultimately desirable for organizations. If so, to what extent are they desirable? One possible explanation of the inverted U-shaped effect of CSPs on stakeholder orientation is that organizations with a long CSP experience reach a higher order level of learning. This allows them to purposively select the stakeholders to sense, learn from, and implement change with based on a proactive strategic sustainability intent. A competing reflection may see this decrease in dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation over time as dangerous: organizations that lose the ability to assess the environment external to their purposive networks are exposed to higher risks, especially in turbulent times. Future studies are needed to expand and inform this discussion.

References

Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2008). Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18, 543–571.

Argyris, C. (1977). Double loop learning in organizations. Harvard Business Review, 55, 115–125.

Armitage, D., Berkes, F., Dale, A., Kocho-Schellenberg, E., & Patton, E. (2011). Co-management and the co-production of knowledge: Learning to adapt in Canada’s Arctic. Global Environmental Change, 21, 995–1004.

Arts, B. (2002). ‘Green Alliances’ of business and NGOs. New styles of self-regulation or ‘Dead-End Roads’? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 9, 26–36.

Austin, J. E. (2000). Strategic collaboration between nonprofits and business. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 29, 69–97.

Austin, J. E., & Seitanidi, M. M. (2012). Collaborative value creation a review of partnering between nonprofits and businesses: Part I. Value creation spectrum and collaboration stages. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41, 726–758.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17, 99–120.

Batie, S. (2008). Wicked problems and applied economics. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 90, 1176–1191.

Berman, S. L., Wicks, A. C., Kotha, S., & Jones, T. M. (1999). Does stakeholder orientation matter? The relationship between stakeholder management models and firm financial performance. The Academy of Management Journal, 42, 488–506.

Biermann, F., Chan, M.-s., Mert, A., & Pattberg, P. (2007). Multi-stakeholder partnerships for sustainable development: Does the promise hold? In P. Glasbergen, F. Biermann, & A. P. J. Mol (Eds.), Partnerships, governance and sustainable development. Reflections on theory and practice (pp. 239–260). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Bitzer, V. (2012). Partnering for change in chains: The capacity of partnerships to promote sustainable change in global agrifood chains? International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 15(B), 13–38.

Clarke, S., & Roome, N. (1999). Sustainable business: Learning-action networks as organizational assets. Business Strategy and the Environment, 8, 296–310.

Clarkson, M. B. E. (1995). A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review, 20, 92–117.

Cuppen, E. (2012). A quasi-experimental evaluation of learning in a stakeholder dialogue on bio-energy. Research Policy, 41, 624–637.

Dahan, N. M., Doh, J. P., & Teegen, H. (2010). Role of nongovernmental organizations in the business–government–society interface: Introductory essay by guest editors. Business and Society, 49, 567–569.

Dentoni, D., Blok, V., Lans, T., & Wesselink, R. (2012a). Developing human capital for agri-food firms’ multi-stakeholder interactions. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 15(A), 61–68.

Dentoni, D., Hospes, O., & Ross, B. (2012b). Managing wicked problems in agribusiness: The role of multi-stakeholder engagements in value creation. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 15(B), 1–12.

Dentoni, D., & Peterson, H. C. (2011). Multi-stakeholder sustainability alliances in agri-food chains: A framework for multi-disciplinary research. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 14, 83–108.

Dierickx, I., & Cool, K. (1989). Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competitive advantage. Management Science, 35, 1504–1511.

Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. E. (1995). The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Academy of Management Review, 20, 65–91.

Duriau, V. J., Reger, R. K., & Pfarrer, M. D. (2007). A content analysis of the content analysis literature in organization studies: Research themes, data sources, and methodological refinements. Organizational Research Methods, 10, 5–34.

Ferrell, O. C., Gonzalez-Padron, T. L., Hult, G. T. M., & Maignan, I. (2010). From market orientation to stakeholder orientation. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 29, 93–96.

Fineman, S., & Clarke, K. (1996). Green stakeholders: Industry interpretations and response. Journal of Management Studies, 33, 715–730.

Fisher, R. J. (1993). Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. Journal of Consumer Research, 20, 303–315.

Freeman, R. E. (2010). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Glasbergen, P. (2007). Setting the scene: The partnership paradigm in the making. In P. Glasbergen, F. Biermann, & A. P. J. Mol (Eds.), Partnerships, governance and sustainable development. Reflections on theory and practice (pp. 1–28). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Glasbergen, P. (2010). Global action networks: Agents for collective action. Global Environmental Change, 20, 130–141.

Glasbergen, P. (2011). Understanding partnerships for sustainable development analytically: The ladder of partnership activity as a methodological tool. Environmental Policy and Governance, 21, 1–13.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. London: Wiedenfeld and Nicholson.

Gray, B. (1989). Collaborating: Finding common ground for multiparty problems. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Gulati, R. (1999). Network location and learning: The influence of network resources and firm capabilities on alliance formation. Strategic Management Journal, 20, 397–420.

Helfat, C. E., Finkelstein, S., Mitchell, W., Peteraf, M. A., Singh, H., Teece, D. J., & Winter, S. G. (2007). Dynamic capabilities: Understanding strategic change in organizations. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Hospes, O., van der Valk, O., & van der Mheen-Sluijer, J. (2012). Parallel development of five partnerships to promote sustainable soy in Brazil: Solution or part of wicked problems? International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 15(B), 39–62.

Hult, G. T. M. (2011). Toward a theory of the boundary-spanning marketing organization and insights from 31 organization theories. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39, 509–536.

Huxham, C. (1993). Collaborative capability: An intra-organizational perspective on collaborative advantage. Public Money and Management, 12, 21–28.

Jawahar, I. M., & McLaughlin, G. L. (2001). Toward a descriptive theory of stakeholder theory: An organizational life-cycle approach. Academy of Management Journal, 26, 397–414.

Jones, T. M., Felps, W., & Bigley, G. A. (2007). Ethical theory and stakeholder related decisions: The role of stakeholder culture. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 137–155.

Kale, P., & Singh, H. (2009). Managing strategic alliances: What do we know now, and where do we go from here? Academy of Management Perspectives, 23(3), 45–62.

Kolk, A., Van Tulder, R., & Kostwinder, E. (2008). Business and partnerships for development. European Management Journal, 26, 262–273.

Laplume, A. O., Sonpar, K., & Reginald, A. L. (2008). Stakeholder theory: Reviewing a theory that moves us. Journal of Management, 34, 1152–1189.

Lawrence, A. T. (2002). The drivers of stakeholder engagement: Reflections on the case of Royal Dutch/Shell. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 6, 71–85.

Le Ber, M. J., & Branzei, O. (2010a). (Re)forming strategic cross-sector partnerships: Relational processes of social innovation. Business and Society, 49, 140–172.

Le Ber, M. J., & Branzei, O. (2010b). Value frame fusion in cross sector interactions. Journal of Business Ethics, 94, 163–195.

Levin, K., Cashore, B., Bernstein, S., & Auld, G. (2012). Overcoming the tragedy of super wicked problems: Constraining our future selves to ameliorate global climate change. Policy Sciences, 45(2), 1–30.

Lund-Thomsen, P. (2009). Assessing the impact of public–private partnerships in the global south: The case of the Kasur Tanneries Pollution Control Project. Journal of Business Ethics, 90, 57–78.

Maak, T. (2007). Responsible leadership, stakeholder engagement, and the emergence of social capital. Journal of Business Ethics, 74, 329–343.

Maignan, I., & Ferrell, O. C. (2004). Corporate social responsibility and marketing: An integrative framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32, 3–19.

Mandarano, L., & Paulsen, K. (2011). Governance capacity in collaborative watershed partnerships: Evidence from the Philadelphia region. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 54, 1293–1313.

Mitchell, R. K., Agle, B. R., & Wood, D. J. (1997). Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review, 22, 853–886.

Murphy, M., Perrot, F., & Rivera-Santos, M. (2012). New perspectives on learning and innovation in cross-sector collaborations. Journal of Business Research, 65, 1700–1709.

Penrose, E. (1959). The theory of the growth of the firm. New York: Wiley.

Pesqueira, L., & Verburg, J. (2012). NGO–business interaction for social change: Insights from Oxfam’s private sector programme. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 15(B), 133–138.

Peteraf, M. A. (1993). The cornerstones of competitive advantage: A resource-based view. Strategic management journal, 14(3), 179–191.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2011). Creating Shared Value How to reinvent capitalism—And unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harvard Business Review, 89, 62–77.

Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). Co-creating unique value with customers. Strategy and Leadership, 32, 4–9.

Rittel, H. W. J., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4, 155–169.

Robinson, L. W., & Berkes, F. (2011). Multi-level participation for building adaptive capacity: Formal agency–community interactions in northern Kenya. Global Environmental Change, 21, 1185–1194.

Roloff, J. (2008). Learning from multi-stakeholder networks: Issue-focussed stakeholder management. Journal of Business Ethics, 82, 233–250.

Rondinelli, D. A., & London, T. (2003). How corporations and environmental groups cooperate: Assessing cross-sector alliances and collaborations. Academy of Management Executive, 17, 61–76.

Scherer, A. G., Palazzo, G., & Seidl, D. (2013). Managing legitimacy in complex and heterogenous environments: Sustainable development in a globalized world. Journal of Management Studies, 50(2), 259–284.

Schreyögg, G., & Sydow, J. (2010). Organizing for fluidity? Dilemmas of organizational forms. Organization Science, 21, 1251–1262.

Seitanidi, M. M. (2010). The politics of partnerships: A critical examination of nonprofit-business partnerships. Dordrecht: Springer.

Seitanidi, M. M., Koufopoulos, D. N., & Palmer, P. (2010). Partnership formation for change: Indicators for transformative potential in cross sector social partnerships. Journal of Business Ethics, 94, 139–161.

Seitanidi, M. M., & Ryan, A. (2007). A critical review of forms of corporate community involvement: From philanthropy to partnerships. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 12, 247–266.

Selsky, J. W., & Parker, B. (2005). Cross-sector partnerships to address social issues: Challenges to theory and practice. Journal of Management, 31, 849–873.

Selsky, J. W., & Parker, B. (2010). Platforms for cross-sector social partnerships: Prospective sensemaking devices for social benefit. Journal of Business Ethics, 94, 21–37.

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. (1994). Grounded theory methodology: An overview. In N. K. Denzin & Y. A. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 273–285). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Suddaby, R. (2006). From the editors: What grounded theory is not. Academy of Management Journal, 49(4), 633–642.

Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28, 1319–1350.

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18, 509–533.

Teegen, H., Doh, J. P., & Vachani, S. (2004). The importance of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in global governance and value creation: An international business research agenda. Journal of International Business Studies, 35, 463–483.

Van Tulder, R. (2012). Sustainable development through strategic partnerships. In Paper presented at the 3rd international symposium on cross sector social interactions, 24–25 May. Rotterdam: University of Erasmus.

Verona, G., & Zollo, M. (2011). Understanding the human side of dynamic capabilities: A holistic model. In M. Easterby-Smith & M. A. Lyles (Eds.), Handbook of organizational learning and management (2nd ed.). Chichester: Wiley.

Vurro, C., Dacin, M. T., & Perrini, F. (2010). Institutional antecedents of partnering for social change: How institutional logics shape cross-sector social partnerships. Journal of Business Ethics, 94, 39–53.

Waddell, S. (2000). Complementary resources: The win–win rationale for partnerships with NGOs. In J. Bendell (Ed.), Terms for endearment: Business, NGOs and sustainable development (pp. 193–206). Sheffield: Greenleaf Publishing.

Waddell, S. (2002). Core competences a key force in business–government–civil society collaborations. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 7, 43–56.

Waddock, S. (2012). Difference making in a world of collapsing boundaries. In Paper presented at the 3rd international symposium on cross sector social interactions, 24–25 May. Rotterdam: University of Erasmus.

Weber, E. P., & Khademian, A. M. (2008). Wicked problems, knowledge challenges, and collaborative capacity builders in network settings. Public Administration Review, 68, 334–349.

Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5, 171–180.

Winter, S. G. (2003). Understanding dynamic capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 24, 991–995.

Yau, O. H. M., Chow, R. P. M., Sin, L. Y. M., Tse, A., Luk, C. L., & Lee, J. S. K. (2007). Developing a scale for stakeholder orientation. European Journal of Marketing, 41, 1306–1327.

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and method. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Thematic Special Issue on: Enhancing the Impact of Cross Sector Partnerships.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Dentoni, D., Bitzer, V. & Pascucci, S. Cross-Sector Partnerships and the Co-creation of Dynamic Capabilities for Stakeholder Orientation. J Bus Ethics 135, 35–53 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2728-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2728-8