Abstract

Breast cancer patients are at increased risk of sexual dysfunction. Despite this, both patients and practitioners are reluctant to initiate a conversation about sexuality. A sexual dysfunction screening tool would be helpful in clinical practice and research, however, no scale has yet been identified as a “gold standard” for this purpose. The present review aimed at evaluating the scales used in breast cancer research in respect to their psychometric properties and the extent to which they measure the DSM-5/ICD-10 aspects of sexual dysfunction. A comprehensive search of the literature was conducted for the period 1992–2013, yielding 129 studies using 30 different scales measuring sexual functioning, that were evaluated in the present review. Three scales (Arizona Sexual Experience Scale, Female Sexual Functioning Index, and Sexual Problems Scale) were identified as most closely meeting criteria for acceptable psychometric properties and incorporation of the DSM-5/ICD-10 areas of sexual dysfunction. Clinical implications for implementation of these measures are discussed as well as directions for further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer worldwide and the most commonly diagnosed female cancer [1]. With high 5-year survival rates (76–92 %) there are increasing numbers of breast cancer survivors [2], leading to a focus on aspects of quality of life (QOL) [3], due to the long-term effects of cancer and its treatment [4, 5]. Most women (50–75 %) diagnosed with breast cancer report persistent difficulties with sexual functioning [6–8]. Biological, psychological, and social factors all contribute to the development of this sexual dysfunction [9]. Neglecting to address these issues may contribute to further distress and relationship difficulties, and possibly impact other aspects of women’s lives [10].

Sexual assessment and counseling are not routinely provided in oncological settings [11], with less than one-third of breast cancer patients reporting having discussed sexuality concerns with a healthcare professional [12], of these few report satisfaction with the consultation [12], and generally these discussions only occur if the medical practitioner raises the subject [13]. Practitioners’ reluctance to initiate these conversations may stem from fears of litigation and over-involvement in non-medical issues, embarrassment, and misleading assumptions held about their patients’ priorities for treatment [14].

Considering the barriers to discussing these issues, an easily administered, reliable, and valid scale measuring sexual functioning may be useful as a screening tool and to help facilitate clinic-based conversations. In research, such a scale may be used to quantify treatment outcomes and side effects. It is important that any such measure incorporates all dimensions of sexual dysfunction, as defined by internationally accepted diagnostic criteria, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5 [15] and International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, ICD-10 [16]. These dimensions include desire to have sexual activity, excitement/arousal, orgasm, pain, and distress/dysfunction.

To date, there have been three published reviews of scales measuring sexual functioning in individuals with cancer [10, 17, 18], none of which specifically focused on breast cancer, which requires separate consideration because (1) breasts are considered symbols of sexuality and feminism in Western cultures, which may lead to adverse impact of breast cancer and treatment on women’s feminine and sexual identity [19]; (2) women report reduced sexual arousal from breast stimulation following breast surgery [20]; and (3) women may experience diminished sexual responsiveness due to hormonal treatments used for managing breast cancer [21].

Prior reviews are also limited in that they: do not reflect current research in this area [17]; reviewed a select number of measures [18]; focused on measures used in all cancers, rather than breast cancer specifically [10, 17, 18]; and, neglected to include sexual functioning subscales incorporated within QOL measures [10, 17, 18], which are often used in treatment outcomes research. Additionally, no reviews have delineated the extent to which the scales incorporate the DSM-5/ICD-10 dimensions of sexual dysfunction.

Unfortunately very few scales used in breast cancer research have actually been validated on this population. For this reason, our review will delineate the psychometric properties of scales applied within this context. Only self-report measures were considered since they are easy to administer, relatively cost-effective, and may be less intrusive than other modes of assessment [22]. The specific aims were to: (1) evaluate the psychometric properties of available measures; and (2) evaluate the extent to which these measures incorporate DSM-5/ICD-10 sexual dysfunction criteria. The psychometric properties reviewed included reliability, validity and responsiveness to change. The definitions of these terms, methods of measurement and psychometric evaluation criteria are presented in Table 1. As sexual dysfunction is a sensitive subject, the patients’ acceptability of scale questions was also evaluated.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

Literature searching using CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed from 1992 to 2013 was conducted using the terms “breast cancer,” “breast neoplasms”, “sexual functioning,” and “sexual dysfunction.” The search was limited to empirical studies published in English language peer-reviewed journals.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The review inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 2. Where the title or abstract indicated that exclusion criteria were met, the study was rejected. Full text articles were accessed when: (1) it was not clear from the title or abstract whether the inclusion criteria were met or what sexual functioning scale was used; and, (2) inclusion criteria were met and the empirical studies for scales were reviewed.

Scale evaluation scoring system

Each included scale was assessed using the following criteria: (1) psychometric properties; and (2) coverage of DSM-5/ICD-10 dimensions of sexual dysfunction [15, 16]. A score was assigned to each scale indicating the extent to which it had adequate psychometric properties and covered the dimensions of sexual dysfunction (see Table 1 for scoring system). Additional points were awarded based on the characteristics of the validation sample, where “1” was given to studies where n > 300, as this is recommended for scale validation [23], and “0.5” where sample sizes were between 200 and 299. Since scale psychometric properties are dependent on the population studied [24], “1” was given if the validation sample included women with breast cancer, and “0.5” if it included cancer patients generally. Scores for the extent to which the DSM-5/ICD-10 dimensions of sexual dysfunction were incorporated were: “1” for each time at least one question covered one of the five domains (Desire, Arousal, Orgasm, Pain, Distress), with a maximum score of 5. Scores for all quality criteria were summed, with a maximum score of 17 (i.e., 12 psychometric property points and 5 for DSM-5/ICD-10 criteria). The first author (IB) rated the measures first, followed by the second author (KS). Any disagreements were discussed until an agreement was reached.

Results

Literature search results

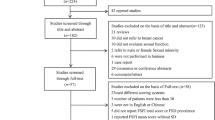

The literature search results are presented in Fig. 1. Out of the 2,192 citations initially identified, 129 studies met the inclusion criteria, using 30 different scales, 18 of which were specifically designed to measure sexual functioning, and 12 were subscales within QOL questionnaires. For the latter, only psychometric properties for sexual functioning subscales were reviewed.

Evaluation of sexual functioning scales

The evaluation of the sexual functioning scales is presented in Tables 3 and 4. Where multiple validation studies for the same scale existed, the results were differentiated by assigning a number in their subscript (e.g., n 1, n 2, denotes sample sizes in two different studies).

Validation sample characteristics

Only four scales (13 %) met the criteria of having adequate sample size and containing women diagnosed with breast cancer (BCPT-SCL [25], CARES [26] Sexual Problem Scale [27], WHOQOL-100 [28]).

Reliability

Seven scales (23 %) met the reliability criteria, that is, having both adequate internal consistency and temporal stability: ASEX [29], FSFI [30], Sexual Self-Schema Scale [31], and the sexual functioning subscales of the CARES [26], MRS [32], QLACS [33], and WHOQOL-100 [28].

Validity

No scales were awarded full scores (6) for their validity studies, but those with the greatest validity evidence (≥4) included: CSDS [58], FSFI [30], Heatherington Intimate Relationship Scale [34], Sexual Self-Schema Scale [31], SQoL-F [67], MRS [32], and WHOQOL-100 [28].

Responsiveness to change

Only five (17 %) scales included evidence of responsiveness to change (ASEX [29], BIRS [36] (GRISS) [37] BCPT-SCL [25], MENQOL [35]). ASEX and BIRS were able to detect improvements in sexual functioning due to treatment (positive change), BCPT-SCL deterioration of functioning due to breast cancer treatment (negative change), and MENQOL and GRISS clinically meaningful change, regardless of direction.

Acceptability to participants

Only four (13 %) of the scales included information on the degree to which the scale questions are acceptable to the participants (GRISS [37], SAQ [38], CARES [26], QLACS [33]).

DSM-IV-TR/ICD-10 aspects

No scales assessed all five aspects of DSM-IV-TR/ICD-10 female sexual dysfunction. FSFI [30], MFSQ [39], SHF [40], Sexual Problem Scale [27] assessed four aspects, while ASEX [29], MOS-SF [41], SAQ [38], Watt’s Sexual Functioning Scale [42], WSBQ-F [43] assessed three.

Overall scores

The overall scores ranged from 2 to 11. The three scales with the highest scores included: FSFI [30] (11), Sexual Problem Scale [27] (10.5), and ASEX [29] (10).

Discussion

Our review has indicated that no one scale obtained full score, indicating superior psychometric properties and coverage of all DSM-5/ICD-10 areas of sexual dysfunction (desire, arousal, orgasm, pain, distress), which is consistent with previous reviews in oncology [10, 17] and general populations [44, 45]. Three highest scoring scales included ASEX, FSFI and Sexual Problems Scale. While FSFI has previously been identified as a good quality scale [10, 18], our review also identified two other scales of similar quality (ASEX, Sexual Problems Scale). In the absence of a “gold standard” sexual dysfunction measure, we recommend that any of these three scales are suitable for use in the breast cancer context, with specific caveats outlined below.

When selecting a measure of sexual dysfunction to use in clinical practice or research, there are three considerations: (1) psychometric properties, to ensure that the variability in scores observed is reflective of the variability in the underlying construct, rather than measurement error [24]; (2) how well the scale measures the construct of interest (DSM-5/ICD-10 aspects of sexual dysfunction); and (3) practical issues (administration, scoring, interpretation).

Only the Sexual Problems Scale has been validated on an adequate-sized breast cancer sample, where it demonstrated good internal consistency and evidence of validity. However, no test–retest data are available, making it less useful for repeated measures. ASEX has been validated on general and psychiatric populations. The FSFI has been validated on community, sexual dysfunction, and gynecologic cancer samples. Hence, for one-off measurement of sexual dysfunction we recommend the Sexual Problems Scale, and for repeated measures the ASEX or FSFI may be more useful.

DSM-5/ICD-10 criteria incorporate when women experience distress due to painful sexual encounters, or disruption in desire, arousal or orgasm. None of the three preferred scales include items measuring distress, and ASEX also does not include items measuring pain; hence, FSFI and the Sexual Problems Scale are recommended as they have the greatest coverage of the DSM-5/ICD-10 dimensions of sexual dysfunction. Additional information about the levels of distress may need to be collected to supplement these scales.

All three scales are relatively brief (ASEX-5, FSFI-19, and Sexual Problems Scale-9 items, respectively) and readily accessible. As yet, these scales do not have electronic versions for ease of administration and scoring. To obtain a total score, ASEX and the Sexual Problems Scale have individual items summed, whereas FSFI’s scoring algorithm is more complex with six subscales being summed to yield a total score. All scales can be interpreted to identify potential areas of sexual dysfunction, and the Sexual Problems Scale also takes into account partner variables (i.e., lack of interest in sex). Additionally, FSFI can only be validly interpreted for individuals experiencing sexual activity in the past month. Therefore, the Sexual Problems Scale is considered most practical, as it is relatively short to administer and score, and it can identify when dysfunction is due to partner difficulties.

This review also highlighted ways in which existing measures can be improved. To make these scales more psychometrically meaningful for breast cancer population, they would benefit from replication of validation studies in this context. Future research should focus on demonstrating concurrent validity, as many validation studies did not report these data. Demonstrating concurrent validity is more difficult when there is no acceptable “gold standard,” but researchers are encouraged to use the three scales identified above for this purpose. Generally, all scales can be further improved by additional items to ensure adequate coverage of all dimensions aspects of sexual dysfunction [15, 16], in particular distress. Although the evaluation of the cultural suitability and sensitivity of scales was beyond the scope of this review, some scales have validation data for different languages and cultures (e.g., FSFI, MFSQ, SAQ, EORTC-BR-23, WHOQOL-100). Future studies should continue to investigate cross-cultural properties of these sexual dysfunction scales.

In conclusion, this comprehensive systematic review builds upon and extends prior work concerning sexual dysfunction in oncology [10, 17, 18], by focusing specifically on the breast cancer context. Strengths of the research are that it was based on a rigorous psychometric evaluation of measures and an assessment of the extent to which existing measures meet the diagnostic criteria for sexual dysfunction [15, 16]. The scoring system provided a systematic way to summarize the extent to which the scales met the psychometric and DSM-V/ICD-10 criteria. The limitation of the review is that it focused only on studies published in the English language, leading to possible bias.

Our conclusions are of equal importance to clinicians and researchers alike, for whom the selection of appropriate measures of sexual dysfunction will facilitate clinical consultation and discussion with patients, or as critical outcomes and endpoints of clinical trials.

References

Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF (2006) Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol 24(14):2137–2150

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2009) Breat Cancer in Australia: an overview. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra

Den Oudsten BL, Van Heck GL, Van der Steeg AFW, Roukema JA, De Vries J (2009) The WHOQOL-100 has good psychometric properties in breast cancer patients. J Clin Epidemiol 62(2):195–205

Mols F, Vingerhoets AJ, Coebergh JW, van de Poll-Franse LV (2005) Quality of life among long-term breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer 41(17):2613–2619

Flynn KE, Jeffery DD, Keefe FJ, Porter LS, Shelby RA, Fawzy MR, Gosselin TK, Reeve BB, Weinfurt KP (2011) Sexual functioning along the cancer continuum: focus group results from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®). Psychooncology 20(4):378–386

Capodice JL, Crew KD, Ortiz-Pride Y, Specht J, Braffman L, Fuentes D, Hershman DL: Survey of the prevalence and severity of sexual dysfunction in breast cancer patients. ASCO Meeting Abstracts 2008, 26(15suppl):9557

Goldfarb S, Dickler M, Patil S, Jia R, Sit L, Damast S, Carter J, Kaplan J, Hudis C, Basch E (2011) Sexual dysfunction in women with breast cancer: prevalence and severity. J Sex Med 8:66

Bloom JR, Stewart SL, Oakley-Girvan I, Banks PJ, Shema S (2012) Quality of life of younger breast cancer survivors: persistence of problems and sense of well-being. Psychooncology 21(6):655–665

Tierney DK (2008) Sexuality: a quality-of-life issue for cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs 24(2):71–79

Jeffery DD, Tzeng JP, Keefe FJ, Porter LS, Hahn EA, Flynn KE, Reeve BB, Weinfurt KP (2009) Initial report of the cancer Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) sexual function committee: review of sexual function measures and domains used in oncology. Cancer 115(6):1142–1153

Krychman ML, Pereira L, Carter J, Amsterdam A (2007) Sexual oncology: sexual health issues in women with cancer. Oncology 71(1–2):18–25

Hawkins Y, Ussher J, Gilbert E, Perz J, Sandoval M, Sundquist K (2009) Changes in sexuality and intimacy following the diagnosis and treatment of cancer: the experience of partners in an sexual relationship with a person with cancer. Cancer Nurs 32(4):271–279

Moreira EDJ, Brock G, Glasser DB, Nicolosi A, Laumann EO, Paik A, Wang T, Gingell C, For The GSSAB Investigators’ Group (2005) Help seeking behaviour for sexual problems: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviours. Int J Clin Pract 59(1):6–16

Hordem AJ, Street AF (2007) Communicating about patient sexuality and intimacy after cancer: mismatched expectations and unmet needs. Med J Aust 186(5):224–227

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mantal Disorders. American Psychiatric Association, Washington DC

World Health Organization (2004) International Classification of Diseases and Health Related Problems. World Health Organization, Geneva

Cull AM (1992) The assessment of sexual function in cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 28(10):1680–1686

Lorenz TA, Stephenson KR, Meston CM (eds) (2011) Validated questionnaires in female sexual function assessment. Humana Press, New York

Langellier KM, Sullivan CF (1998) Breast talk in breast cancer narratives. Qual Health Res 8(1):76–94

Wilmoth MC (2001) The aftermath of breast cancer: an altered sexual self. Cancer Nurs 24(4):278–286

Mok K, Juraskova I, Friedlander M (2008) The impact of aromatase inhibitors on sexual functioning: current knowledge and future research directions. Breast 17(5):436–440

Fenton KA, Johnson AM, McMAnus S, Erens B (2001) Measuring sexual behaviour: methodological challenges in survey research. Sex Transm Inf 77:84–92

Rouquette A, Falissard B (2011) Sample size requirements for the internal validation of psychiatric scales. Int J Method Psychiatr Res 20(4):235–249

Streiner DL, Norman GR (1995) Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Terhorst L, Blair-Belansky H, Moore PJ, Bender C (2011) Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the BCPT symptom checklist with a sample of breast cancer patients before and after adjuvant therapy. Psychooncology 20(9):961–968

Coscarelli A, Heinrich RL (1988) Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System (CARES): manual. CARES Consultants, Santa Monica

Perez M, Liu Y, Schootman M, Aft RL, Schechtman KB, Gillanders WE, Jeffe DB (2010) Changes in sexual problems over time in women with and without early-stage breast cancer. Menopause 17(5):924–937

The WHOQOL Group (1998) The World Health Organization quality of life assessment: development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med 46(12):1569–1585

McGahuey CA, Gelenberg AJ, Laukes CA, Moreno FA, Delgado PL, McKnight KM, Manber R (2000) The Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX): reliability and Validity. J Sex Marital Ther 26(1):25–40

Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, Ferguson D, D’Agostino R Jr (2000) The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther 26(2):191–208

Andersen BL, Cyranowski JM (1994) Women’s sexual self-schema. J Pers Soc Psychol 67(6):1079–1100

Heinemann K, Ruebig A, Potthoff P, Schneider HP, Strelow F, Heinemann LA, Do MT (2004) The Menopause Rating Scale (MRS) scale: a methodological review. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2:45–53

Avis NE, Ip E, Foley KL (2006) Evaluation of the quality of life in Adult Cancer Survivors (QLACS) scale for long-term cancer survivors in a sample of breast cancer survivors. Health Qual Life Outcomes 4:92–103

Hetherington SH, Soeken KL (1990) Measuring changes in intimacy and sexuality: a self-administered scale. J Sex Educ Ther 16:155–163

Hilditch JR, Lewis J, Peter A, van Maris B, Ross A, Franssen E, Guyatt GH, Norton PG, Dunn E (1996) A menopause specific quality of life questionnaire: development and psycholmetric properties. Maturitas 24:161–175

Hormes JM, Lytle LA, Gross CR, Ahmed RL, Troxel AB, Schmitz KH (2008) The body image and relationships scale: development and validation of a measure of body image in female breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 26(8):1269–1274

Rust J, Golombok S (1986) The GRISS: a psychometric instrument for the assessment of sexual dysfunction. Arch Sex Behav 15(2):157–165

Thirlaway K, Fallowfield L, Cuzick J (1996) The sexual activity questionnaire: a measure of women’s sexual functioning. Qual Life Res 5(1):81–90

McCoy NL (2000) The McCoy female sexuality questionnaire. Qual Life Res 9:739–745

Nowinski JK, LoPiccolo J (1979) Assessing sexual behaviours in couples. J Sex Marital Ther 5:225–243

Sherbourne CD (ed) (1992) Social functioning: sexual problems measures. Duke University Press, Durham

Watts RJ (1982) Sexual functioning, health beliefs, and compliance with high blood pressure medications. Nurs Res 31(5):278–283

Wilmoth MC, Tingle LR (2000) Development and psychometric testing of the Wilmoth Sexual Behaviors Questionnaire-Female. Can J Nurs Res 32(4):135–151

Arrington R, Cofrancesco J, Wu AW (2004) Questionnaires to measure sexual quality of life. Qual Life Res 13(10):1643–1658

Daker-White G (2002) Reliable and valid self-report outcome measures in sexual (dys) function: a systematic review. Arch Sex Behav 31(2):197–209

Webb NM, Shavelson RJ, Haertel EH (eds) (2007) Reliability coefficients and generalizability theory. Elsevier, Oxford

Lounsbury JW, Gibson LW, Saudargas RA (2006) Scale development. In: Leong FT, Austin JT (eds) The psychology research handbook: a guide for graduate students and research assisstants, 2nd edn. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Aday LA, Cornelius LJ (2006) Designing and conducting health surveys. Josey-Bass, 3rd edn. Wiley, San Francisco

Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH (1994) Psychometric theory, 3rd edn. McGraw Hillss, New York

McDowell I, Newell C (1996) Measuring health: a guide to rating scales and questionnaires, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, New York

Hemphill JF (2003) Interpreting the magnitudes of correlation coefficients. Am Psychol 58(1):78–80

Dickter DN (2006) Basic statistical analysis. In: Leong FT, Austin JT (eds) The psychology research handbook: a guide for graduate students and research assistants. Sage Publishing, Thousand Oaks

Schuck P, Zwingmann C (2003) The ‘smallest real difference’ as a measure of sensitivity to change: a critical analysis. Int J Rehabil Res 26(2):85–91

Husted JA, Cook RJ, Farewell VT, GLadman DD (2000) Methods for assessing responsiveness: a critical review and recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol 53:459–468

Byerly MJ, Nakonezny PA, Fisher R, Magouirk B, Rush AJ (2006) An empirical evaluation of the Arizona Sexual Experience Scale and a simple one-item screening test for assessing antipsychotic-related sexual dysfunction in outpatients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Schizophr Res 81(2–3):311–316

Boyarsky BK, Haque W, Rouleau MR, Hirschfeld RMA (1999) Sexual functioning in depressed outpatients taking mirtazapine. Depress Anxiety 9(4):175–179

Speck RM, Gross CR, Hormes JM, Ahmed RL, Lytle LA, Hwang WT, Schmitz KH (2010) Changes in the Body Image and Relationship Scale following a one-year strength training trial for breast cancer survivors with or at risk for lymphedema. Breast Cancer Res Treat 121(2):421–430

McCall K, Meston C (2006) Cues resulting in desire for sexual activity in women. J Sex Med 3(5):838–852

Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N (1979) The DSFI: a multidimentional measure of sexual functioning. J Sex Marital Ther 5(3):244–281

Meston CA (2003) Validation of the Female Sexual Funcion Index (FSFI) in women with female orgasmic disorder and women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Marital Ther 29(1):39–46

Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R (2005) The female sexual function index (FSFI): cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther 31(1):1–20

Baser RE, Li Y, Carter J (2012) Psychometric validation of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) in cancer survivors. Cancer 118(18):4606–4618

Hetherington SH (ed) (1988) Intimate relationship scale. Graphic Publishing, Iowa City

Berglund G, Nystedt M, Bolund C, Sjoden PO, Rutquist LE (2001) Effect of endocrine treatment on sexuality in premenopausal breast cancer patients: a prospective randomized study. J Clin Oncol 19(11):2788–2796

Majerovitz DS, Revenson TA (1994) Sexuality and rheumatic disease. Arthritis Rheum 7(1):29–34

Creti L, Fichten CS, Amsel R, Brender W, Schover LR, Kalogeropoulos D, Libman E (1998) Global sexual functioning: a single summary score for Nowinski and LoPiccolo’s sexual history form. In: Davis CM, Yarber WL, Bauserman R, S G, Davis SL (eds) Handbook of sexuality-related measures. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Symonds T, Boolell M, Quirk F (2005) Development of a questionnaire on sexual quality of life in women. J Sex Marital Ther 31(5):385–397

Cella DF, Land SR, Chang CH, Day R, Costantino JP, Wolmark N, Ganz PA (2008) Symptom measurement in the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (BCPT) (P-1): psychometric properties of a new measure of symptoms for midlife women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 109(3):515–526

Stanton AL, Bernaards CA, Ganz PA (2005) The BCPT symptom scales: a measure of physical symptoms for women diagnosed with or at risk for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 97(6):448–456

Ganz PA, Schag CAC, Lee JJ, Sim MS (1992) The CARES: a generic measure of health-related quality of life for patients with cancer. Qual Life Res 1(1):19–29

Sprangers MAG, Groenvold M, Arraras JI, Franklin J, Velde AT, Muller M, Franzini L, Williams A, De Haes HCJM, Hopwood P et al (1996) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire module: first results from a three-country field study. J Clin Oncol 14(10):2756–2768

Thomson HJ, Winters ZE, Brandberg Y, Didier F, Blazeby JM, Mills J (2013) The early development phases of a European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) module to assess patient reported outcomes (PROs) in women undergoing breast reconstruction. Eur J Cancer 49(5):1018–1026

Gordon NH, Siminoff LA (2010) Measuring quality of life of long-term breast cancer survivors: the Long Term Quality of Life-Breast Cancer (LTQOL-BC) Scale. J Psychosoc Oncol 28(6):589–609

Radtke JV, Terhorst L, Cohen SM (2011) The Menopause-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire: psychometric evaluation among breast cancer survivors. Menopause 18(3):289–295

Kulasingam S, Moineddin R, Lewis JE, Tierney MC (2008) The validity of the Menopause Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire in older women. Maturitas 60(3–4):239–243

Derogatis LR (1986) The Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale (PAIS). J Psychosom Res 30(1):77–91

Merluzzi TV, Martinez Sanchez MA (1997) Factor structure of the psychosocial adjustment to illness scale (self-report) for persons with cancer. Psychol Assess 9(3):269–276

Rodrigue JR, Kanasky WF, Jackson SI, Perri MG (2000) The psychosocial adjustment to illness scale–self report: factor structure and item stability. Psychol Assess 12(4):409–413

Hunter M (1992) The women’s health questionnaire: a measure of mid-aged women’s perceptions of their emotional and physical health. Psychol Health 7(1):45–54

Hunter M, The Women’s Health Questionnaire (WHQ) (2000) The development, standardization, and application of a measure of mid-aged women’s emotional and physical health. Qual Life Res 9:733–738

Hunter M, Battersby R, Witehead M (2008) Reprint of relationships between psychological symptoms, somatic complaints and menopausal status. Maturitas 61(1–2):95–106

Molzahn AE, Page G (2006) Field testing the WHO-QOL in Canada. Can J Nurs Res 38(3):106–123

Acknowledgments

The current review was undertaken with co-funding support from the National Breast Cancer Foundation and Cancer Australia.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bartula, I., Sherman, K.A. Screening for sexual dysfunction in women diagnosed with breast cancer: systematic review and recommendations. Breast Cancer Res Treat 141, 173–185 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-013-2685-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-013-2685-9