Abstract

To investigate relationships between hemodynamic responses and neural activities in the somatosensory cortices, hemodynamic responses by near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) and electroencephalograms (EEGs) were recorded simultaneously while subjects received electrical stimulation in the right median nerve. The statistical significance of the hemodynamic responses was evaluated by a general linear model (GLM) with the boxcar design matrix convoluted with Gaussian function. The resulting NIRS and EEGs data were stereotaxically superimposed on the reconstructed brain of each subject. The NIRS data indicated that changes in oxy-hemoglobin concentration increased at the contralateral primary somatosensory (SI) area; responses then spread to the more posterior and ipsilateral somatosensory areas. The EEG data indicated that positive somatosensory evoked potentials peaking at 22 ms latency (P22) were recorded from the contralateral SI area. Comparison of these two sets of data indicated that the distance between the dipoles of P22 and NIRS channels with maximum hemodynamic responses was less than 10 mm, and that the two topographical maps of hemodynamic responses and current source density of P22 were significantly correlated. Furthermore, when onset of the boxcar function was delayed 5–15 s (onset delay), hemodynamic responses in the bilateral parietal association cortices posterior to the SI were more strongly correlated to electrical stimulation. This suggests that GLM analysis with onset delay could reveal the temporal ordering of neural activation in the hierarchical somatosensory pathway, consistent with the neurophysiological data. The present results suggest that simultaneous NIRS and EEG recording is useful for correlating hemodynamic responses to neural activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Various functional neuroimaging techniques have been developed since Roy and Sherrington (1890) reported that blood supply increases in response to neuronal activities. Studies using positron emission tomography (PET) have reported that neuronal activities could be estimated by an increase in cerebral blood volume or flow (Fox and Raichle 1986; Fox et al. 1988). Hemodynamic responses to neuronal activities have been measured using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) (Ogawa et al. 1993) and near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) (Jobsis 1977). NIRS can easily and non-invasively measure changes in oxy-hemoglobin (Oxy-Hb), deoxy-hemoglobin (Deoxy-Hb) and total hemoglobin (Total-Hb) based on local neuronal activities (Chance et al. 1993; Hoshi and Tamura 1993; Kato et al. 1993; Villringer et al. 1993).

Each method has advantages and disadvantages. The spatial resolution and depth penetration of NIRS are worse than those of fMRI; furthermore, absolute values of hemodynamic responses cannot be measured by NIRS because the optical path length is unknown (Hoshi 2003). However, the temporal resolution is higher in NIRS than in fMRI. Furthermore, NIRS is sensitive to hemodynamic changes at the capillary level while fMRI or blood-oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) signals are only sensitive at the small venous vessel level (Yamamoto and Kato 2002). This suggests that NIRS measurements are more directly correlated to neuronal activities than fMRI. Recently, several studies reported simultaneous recording using different non-invasive methods to compensate for the methods’ respective disadvantages, such as NIRS with fMRI (Kleinschmidt et al. 1996; Punwani et al. 1998; Toronov et al. 2001, 2003; Mehagnoul-Schipper et al. 2002; Strangman et al. 2002; Chen et al. 2003; Siegel et al. 2003; Seiyama et al. 2004; Huppert et al. 2006; Schroeter et al. 2006), or NIRS with electroencephalograms (EEGs) (Plichta et al. 2006; Koch et al. 2006; Roche-Labarbe et al. 2007).

In the present study, to investigate neuro-hemodynamic relationships using NIRS, we simultaneously recorded neural and hemodynamic responses using NIRS and EEG from the whole brain during electrical stimulation of the median nerve. Current source generators (dipoles) and current source density (CSD) maps of somatosensory evoked potentials (SEPs) were compared with hemodynamic responses measured by NIRS. Previous PET and fMRI studies in humans have assessed cerebral hemodynamic changes following electric nerve stimulation (Backes et al. 2000; Gerrits et al. 1998; Ibanez et al. 1995; Kampe et al. 2000; Puce et al. 1995; Spiegel et al. 1999), and relationships between SEP amplitudes and BOLD responses (Arthurs et al. 2000). Recently, significant relations between local field potentials and hemodynamic responses have been reported in the somatosensory cortex of anesthetized animals (Sheth et al. 2004; Devor et al. 2003). However, no reports have shown the relationships between hemodynamic responses measured by NIRS and neural activities of SEPs in awake human subjects.

Previous EEG and MEG studies reported that neuronal activities moved from the contralateral primary somatosensory (SI) area to the contralateral and ipsilateral parietal association cortices (Hayashi et al. 1995a, b; Kanno et al. 2003). However, although previous extensive NIRS studies reported primary hemodynamic responses, few NIRS studies reported secondary hemodynamic responses. In the present study, we report temporal ordering of hemodynamic responses elicited by median nerve stimulation by means of introducing a new parameter to denote hemodynamic responses (onset delay, see “Materials and methods”).

The above EEG and NIRS data were initially analyzed in each subject using realistic head models. Then, the analyzed data were compared using all of the subjects. This approach, in which the data were initially analyzed in the individual subjects while the stereotaxic coordinates of the individual subjects were preserved, is useful since the results could be directly applied to stereotaxic neurosurgery. Our previous studies reported usefulness of this approach in clinical application (Hayashi et al. 1995a, b; Endo et al. 1997).

Materials and Methods

Subjects and Electrical Stimulation

Eighteen healthy subjects were enrolled (mean age 21.7 years; range 18–25 years; 11 females, 7 males; all right-handed). All subjects were treated in strict compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and U.S. Code of Federal Regulations for protection of human subjects. The experiments were conducted with the understanding and consent of each subject, and approved by the ethical committee at our university.

The subjects were seated in a shielded chair in a lit quiet 3 × 3 × 5 m3 shielded room with an exhaust fan to re-ventilate the room air continuously. A head cap for simultaneous NIRS and EEG recording was set on the head of the subject (see next section for details). Their right hand was put on an armrest for electrical median nerve stimulation. Electrical stimulation with 20 μs duration was delivered to the right median nerve at the wrist with an intensity of 90% motor threshold. Stimulus frequency was varied between 2, 5 and 10 Hz. One block of electrical stimulation lasted for 30 s followed by 60 s rest. A total of 12 blocks were presented (Tanosaki et al. 2003).

Head Cap

We have developed a head cap for NIRS and EEG (Fig. 1a) (FLASH-PLUS; Shimadzu Co. Ltd., Japan). The head cap consists of polypropylene plates (4.3 cm long and 1.5 cm wide), 4 of which together form a square (Fig. 1b). This material is sufficiently flexible to be deformed to fit the surface of the head (Fig. 1b). There are circular holes for NIRS probes in the 4 vertexes of the squares, and the distance between the centers of the holes was set to 3 cm. This head cap can snugly fit various head sizes and shapes while the distance between any two NIRS probes is constant (3 cm) by a new adjustment mechanism using the Guss–Bonnet theorem (Banados et al. 1994; Cummings 2001). Furthermore, sockets for EEG electrodes made from an acetal resin (Biosemi Co. Ltd., Netherlands) were attached to the center of the polypropylene plates (Fig. 1b). A black swimming cap made from nylon and polyurethane was used to line the inside of the head cap to block unnecessary light.

Head cap for simultaneous recording of NIRS and EEGs (a, b) and parameters of the Gaussian function (c). a A subject wearing the head cap. The dotted arrow indicates a socket for an EEG electrode. The solid arrow indicates a hole for a NIRS probe. A swimming cap is used to line the head cap to block unnecessary light. b Polypropylene plates (4.3 cm long and 1.5 cm wide), 4 of which form a square, make up the head cap. The distance between NIRS holes was 3 cm, and the EEG sockets were located midway between two NIRS holes. These materials are flexible so that the head cap could be adjusted to fit subjects with various head shapes. c Parameters to denote Gaussian function. OD onset delay, PD peak delay, TD total delay

We simultaneously recorded neural and hemodynamic data from 32 electrodes and 103 fNIRS channels using this head cap. NIRS probes were arranged to cover the whole brain except the occipital lobe since right median nerve stimulation was supposed not to elicit hemodynamic responses in the occipital lobe, while EEG electrodes were arranged to cover the whole brain including the occipital lobe to estimate dipoles of SEPs.

fNIRS Recording

Two NIRS instruments (OMM 3000, Shimadzu, Co. Ltd) were combined to cover the whole brain. The whole system consisted of 30 optical sources and 32 detectors, and consequently resulted in a total of 103 recording channels. The distance between the NIRS sources and detectors was set at 3 cm, and the sources and detectors were positioned crosswise. The midpoints between the sources and detectors were called ‘NIRS channels’; hemodynamic responses under these channels were detected by the NIRS source and detectors. Three different wavelengths (708, 805, 830 nm) with a pulse width of 5 ms were used to detect hemodynamic responses. The mean total irradiation power was less than 1 mW. Changes in the Hb concentration [∆Oxy-Hb, ∆Deoxy-Hb, and ∆Total-Hb (∆Oxy Hb + ∆Deoxy Hb)] from the control baseline were estimated based on a modified Lambert–Beer law (Seiyama et al. 1988; Wray et al. 1988). Since continuous wave systems cannot measure optical path length (Hoshi 2003), and no specific value for the optical path length was adopted according to the previous literature (e.g., Duncan et al. 1996), the scale unit was molar-concentration multiplied by the unknown path length (mmol × cm). The depth of light penetration from the surface of the brain in adult humans has been reported to range from 0.5 to 2 cm (Fukui et al. 2003).

After recording, 3-D locations of fNIRS probes were measured by a Digitizer (Real NeuroTechnology Co. Ltd., Japan) in reference to the nasion and bilateral external auditory meatus. The location of each NIRS channel was determined by stereotaxic superimposition on the surface of the 3-D MRI reconstructed brain of each subject. For 3-D MRI, thin-slice 3-D sagittal T1-weighted gradient echo MR images were obtained at 1.5 T using a specific protocol tailored for reconstruction. All 15 subjects had the following protocol: (TR/TE/NSA) 25/5/1, flip angle 10, FOV 87.5 cm, matrix 256 × 256, 1.0 mm contiguous slices, obtained in a plane parallel to the brain stem.

EEG Recording

EEGs were recorded using a BioSemi Active Two amplifier system with high-impedance electrodes (BioSemi Co. Ltd., the Netherlands). After setting up the head cap, electrode gel was applied in the holes of the EEG sockets, and EEG electrodes were clicked into the holes. The 32 electrode sockets were set on the head cap so that they were always positioned at the midpoint between NIRS sources and detectors. This means that the locations of the EEG electrodes coincided with the NIRS channels where the hemodynamic responses were recorded. Furthermore, electrodes were placed at the left and right mastoids, the outer canthi of both eyes (HEOG), and the infraorbital and supraorbital regions of the eye (VEOG). Two additional electrodes were used as a reference and ground, respectively. Electrode offset values (corresponding to input impedance) of all the electrodes were controlled to be less than ±5 mV (Metting van Rijin et al. 1990). The EEG data were digitized without filtering at a sampling rate of 2 kHz using a 24-bit A/D converter, and stored on a hard disk. After recording, the positions of all electrodes were measured using the Digitizer (Real Neuro-Technology, Co. Ltd., Japan).

Data Analyses

fNIRS

Three parameters of hemodynamic responses (changes in Oxy-Hb, Deoxy-Hb and Total-Hb) are assessed by NIRS. In the present study, we focused on changes in Oxy-Hb, which has been reported to be sensitive to neuro-hemodynamic relationships in NIRS studies (Hoshi et al. 2001; Strangman et al. 2002; Yamamoto and Kato 2002). These NIRS data were summed and averaged in reference to the onset of each stimulation block. These averaged responses were corrected for baseline activity from −10 to 0 s before electrical stimulation, and the corrected data were stereotaxically superimposed on the 3-D-MRI of each subject. Then, hemodynamic topographical brain images were reconstructed by linear interpolation (see the section below for interpolation of the NIRS data).

A stimulus–response relationship was analyzed at the NIRS channels on the contralateral SI area with maximum responses in each subject. Peak hemodynamic response over the stimulation period for 30 s was measured for each stimulus frequency in each subject. Then, these peak hemodynamic responses were averaged across the subjects for each stimulation frequency (2, 5, 10 Hz). These data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Post hoc tests were performed using the Bonferroni test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Statistical significance of hemodynamic responses was assessed by a general linear model (GLM) (Schroeter et al. 2004); the time course of ∆Oxy-Hb was correlated with the design matrix using a boxcar function (i.e., a function with two possible values: 1 and −1). The model equation, including the observation data, design matrix and the error term, was convoluted with a Gaussian kernel (Schroeter et al. 2004). According to previous fMRI studies (Hess et al. 2000: Longothetis et al. 2001; Pouratian et al. 2002; Yamamoto and Kato 2002; Huettel 2004) and the present results (see “Results”), a 6-s delay was imposed between the onset and peak of the function using a positively accelerated exponential function (Gaussian function) (defined as ‘peak delay’) to account for the response delay between neural and hemodynamic responses (Fig. 1c).

Estimation of Temporal Ordering of Neural Activation by GLM Analysis of Hemodynamic Responses

To account for the response delay in the higher sensory association cortices in the hierarchical sensory pathway, we introduced a delay of the onset of boxcar function (defined as ‘onset delay’) (Fig. 1c); the statistical significance of hemodynamic responses was similarly evaluated by GLM when the whole boxcar function with a 6-s peak delay was further delayed from 5 to 15 s. All statistical significance for GLM analysis was based on an adjusted alpha level of less than 0.001, which corresponded to T values greater than 3.0.

To statistically analyze the effects of onset delay, the number of NIRS channels with statistically significant hemodynamic responses in the parietal cortex during 10 Hz electrical stimulation was counted separately in the left and right parietal lobe for each onset delay (i.e., 0, 5, 10, 15 s) with a constant peak delay (6 s). The numbers of NIRS channels with significant responses were averaged across the all subjects and analyzed by 2-way ANOVA with two factors (side × onset delay). When a significant interaction was found, post hoc tests to compare the numbers between the two hemispheres were performed using a test of simple main effect.

Previous fMRI studies manipulated ‘peak delay’ instead of ‘onset delay’ in the auditory cortex (Kruggel and von Cramon 1999), as well as onset delay (Schacter et al. 1997; Buckner et al. 1996, 1998; Bagshaw et al. 2004; Gotman et al. 2005). To compare the results using onset delay with those using peak delay in GLM analysis, all data were also re-analyzed by the GLM with different peak delays and no onset delay. Peak delay was set at 6, 11, 16, and 21 s so that the total delay time (Fig. 1c) from onset of electrical stimulation to the peak of the Gaussian function was the same as that in the GLM analysis with different onset delays (0, 5, 10 and 15 s) and a constant peak delay (6 s). The resultant T values in the NIRS channels at the contralateral SI area and bilateral somatosensory association cortex were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA with two factors (side × peak delay). All statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. These statistical analyses were performed with a commercial statistical package (SPSS Ver. 10.0.7J, SPSS Inc.).

Interpolation Method of the NIRS Data

Hemodynamic topographical brain images were reconstructed by linear interpolation of the above NIRS data. First, the polygon mesh models of the scalp and brain surface were generated using the Marching cube method (Lorensen and Cline 1987). The location of the NIRS channel was defined as the center between the transmission and receiving NIRS probes, and was superimposed on the mesh model of the scalp. The mesh points of the NIRS channels on the brain were estimated from the corresponding mesh points on the scalp (Okamoto et al. 2004). The inverse distance weighting (IDW) method (Shepard 1968) was used to interpolate a NIRS value (F) at a given mesh point (interpolation point) on the brain using known NIRS values at scattered known neighborhood NIRS channel points (number of the neighborhood NIRS channel points, n). The value F is obtained based on a following interpolating function:

where w i is a weight function assigned to each neighborhood NIRS channel point, and f i is a known NIRS value at a known NIRS channel point. The weight function is obtained from the following equation:

where p is an arbitrary positive real number called the power parameter (typically, p = 2) and d i is distance between the known NIRS channel point and the interpolation point. The number of the neighborhood NIRS channel points determines how many NIRS channel points with the known NIRS values are included in the IDW. This number can be specified in terms of a radius (typically, 24 mm), where a center of the circle is the given interpolation point with F. The minimum number of the neighborhood NIRS channel points is set as 2.

EEG Analysis

The EEG data were off-line re-referenced to a calculated linked averaged reference (Brain Vision Analyzer, Ver. 1.05). The EEG data were segmented between −100 and 100 ms in reference to the onset of electrical stimulation, and somatosensory potentials (SEPs) were summed and averaged in all channels. Furthermore, all signals were off-line filtered (bandpass 1.6–500 Hz). HEOG and VEOG artifacts were corrected using the algorithm of Gratton et al. (1983). Epochs including an EEG exceeding ±100 μV were discarded from the data. The mean voltage during 100-ms pre-stimulus period served as a baseline, and the EEG data were corrected for the baseline.

Current source generators (i.e., dipoles) of SEPs were estimated by a dipole tracing (DT) method (Advanced Neuro Technology) (He et al. 1987; Nishijo et al. 1994; Hayashi et al. 1995a, b; Homma et al. 1994; Ikeda et al. 1998; Takakura et al. 2003). Briefly, the DT method can approximate surface potential distributions of human EEGs or evoked potentials to equivalent dipoles by the boundary element method using a realistic 3-layer (scalp–skull–brain, SSB) head model based on 3-D MRI. The boundary element method used in the present study was reported previously in detail by Musha and Okamoto (1999). In this forward calculation, the conductivity ratios for scalp, skull, and brain were set as 1:1/80:1, respectively (Ikeda et al. 1998). The actual potential distributions recorded from the scalp electrodes (Vobs) were compared to the calculated potential distribution (Vcal) for equivalent current dipoles. Following the simplex method (He et al. 1987), the location, orientation, and amplitude of equivalent dipoles in the 3-D head model were adjusted to obtain the best fit between the recorded potential distribution and potentials calculated from the equivalent dipoles. In this simplex method, we set up six initial points that were uniformly distributed in the brain. Thus, the locations and vector moments of dipoles were changed within the head model until the squared difference between the actual potential distribution (Vobs) and the calculated potential distribution (Vcal) was minimal. The RMS (root-mean-square) quality of fit (dipolarity) was defined by {1 − Σ(Vobs − Vcal)2/Σ(Vobs)2}1/2 × 100 (%), where Vobs and Vcal were the observed and calculated potentials at each electrode. Values above 94% indicate agreement between the estimated dipoles and the observed potential (He et al. 1987; Nishijo et al. 1994; Hayashi et al. 1995a, b; Homma et al. 1994; Ikeda et al. 1998). According to the previous studies (Hayashi et al. 1995a, b; Arezzo et al. 1981), we analyzed the dipoles of human P22 and P45, which dipoles were supposed to be located at the primary sensory hand area and the superior parietal lobule (SPL) (areas 5 and 7), respectively.

Although the CSD results indicated ipsilateral activity in the parietal cortex (see “Results”), only the contralateral dipoles were evaluated and analyzed. In the present study, amplitudes of the SEPs were larger over the contralateral than ipsilateral hemispheres. When these data were applied to DT analysis in 2-dipole estimation, dipoles in the contralateral hemisphere were localized in a restricted true region while those in the ipsilateral hemisphere were scattered more widely. This difference in dipole distribution was ascribed to a low signal-to noise (S/N) ratio due to small amplitudes of the SEPs in the ipsilateral hemisphere. We confirmed this phenomenon in a computer simulation study (Shibata et al. 2002). Based on these results, we applied the SEP data to DT analysis, but analyzed dipoles only in the contralateral hemisphere.

Correlation Between fNIRS and EEG Data

First, locations of the dipoles of P22 were compared with the locations (defined as ‘NIRS point’) where maximum hemodynamic responses (∆Oxy-Hb) were observed. The hemodynamic responses measured by the NIRS channels were supposed to come from the brain areas located more than 1.5 cm from the surface of the brain since light waves for NIRS penetrate about 2–3 cm from the surface of the head (McCormick et al. 1992; Hock et al. 1997). In the present study, the 3-D distances between dipoles of P22 and the ‘NIRS point’ were calculated using the data for 10 Hz electrical stimulation.

Second, based on the surface Laplacian estimate, the current source density (CSD) was calculated using commercially available software (Brain Vision Analyzer software) (Ver. 1.05, Brain Products, GmbH, USA). The CSD distributions show the scalp areas where the current flow either emerges from the brain onto the scalp (sources) or enters from the scalp into the brain (sink). CSD data are independent of the reference electrode site (Giard et al. 1990), and are much less affected by distant, far-field generators than by generators closer to the surface (Srinivasan 2005). Therefore, CSD distributions are considered a better reflection of the underlying cortical activities than potential maps (Srinivasan 2005). Correlation between distributions of CSD and hemodynamic responses (∆Oxy-Hb) was evaluated by Pearson’s correlation coefficients. The following 21 pairs of EEG electrodes and NIRS channels (Ch) were used to calculate spatial similarity. These electrodes and channels of the pairs were located in the same positions: Fc1 (EEG)-Ch52 [NIRS; right (R)], FC5-Ch8 [NIRS; left (L)], C3-Ch2 (L), T7-Ch16 (L), CP5-Ch10 (L), CP1-Ch36 (R), P3-Ch25 (L), Cz-Ch32 (R), Pz-Ch42 (R), FC2-Ch51(R), CP2-Ch38 (R), C4-Ch2 (R), P4-Ch25 (R), FC6-Ch8 (R), CP6-Ch10 (R), T8-Ch16 (R), AF3-Ch36 (L), Fp1-Ch31 (L), Fp2-Ch33 (L), AF4-Ch38 (L), Fz-Ch42 (L). CSD values at these electrodes were measured at the peak latency of P22, while hemodynamic responses at these NIRS channels were measured at the moment when parietal channels showed maximum values.

Results

Analyses of Neurophysiological Data

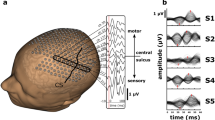

The average current intensity of electrical median nerve stimulation for SEPs was 8.3 ± 0.66 mA (mean ± SEM) (ranging from 3.8 to 10.29). The EEG data derived from three subjects were discarded, since the signal-to-noise ratio was low even at a high stimulation frequency. The following components of SEPs elicited by right median nerve stimulation were recorded from the parietal electrodes in all remaining 15 subjects. Typical examples recorded from a single subject are shown in Fig. 2. In the electrodes around the contralateral left parietal electrodes (e.g., C3, T7, CP5), positive waves were recorded 22 ms after electrical stimulation (P22). Figure 3a shows a topographical map of P22 of the same subject as shown in Fig. 2. Positive potentials were observed around the left sensorimotor cortex. Then, positive waves at the latency of 47 ms (P47) were recorded from the more posterior electrodes (e.g., CP5, P3, P7). These SEPs were consistent with those of previous reports (Arezzo et al. 1979, 1981; Allison et al. 1989a, b).

Typical recording from the 32 electrodes of SEPs derived from a single subject elicited by electrical stimulation of the right median nerve. a Top view of the head indicating locations of the electrodes; R right, L left. b Averaged SEPs when 10-Hz stimulation was applied. In this and the following figures, stimuli were delivered at 0 ms. A total of 12 blocks of the data (one block, 30 s) were averaged

Topographies of SEPs at the latency of P22 (a) and those of averaged raw hemodynamic responses (changes in Oxy-Hb concentration) 5 s after onset of median nerve stimulation (b). SEPs and Oxy-Hb hemodynamic responses were simultaneously recorded from the same subject as that in Fig. 2

Current source density (CSD) was estimated in all subjects. Figure 4A shows waveforms of CSD at the same locations as the electrodes shown in Fig. 2, and Fig. 4B shows the CSD map at each indicated time. CSD increased in the contralateral (left) parietal area not only at the latency of P22 (Ba; 22 ms), but also at the latency of P47 (data not shown), and finally disappeared at 100 ms latency (Bc; 100 ms). It is noted that it also increased around the ipsilateral parietal area at P47 (Bb; 47 ms), although its intensity was much lower than that in the contralateral parietal area. These data suggest that weak synaptic activity was also elicited in the ipsilateral parietal area at a longer latency than in the contralateral parietal area.

Examples of current source density (CSD) waveforms (A) and CSD maps (B). EEG data (SEPs) shown in Fig. 2 were subjected to CSD transformation. Isolatency dotted lines (a), (b), (c) in (A) are at the approximate peaks of P22, P47, and at 100 ms latency, respectively, and latencies of the CSD maps in (B) (a), (b), (c) correspond to those in (A)

Dipoles were estimated in all 15 averages, and only equivalent dipoles in the approximate peak latency range of each SEP component with dipolarity exceeding 94% were evaluated in the contralateral hemisphere. Figure 5 shows some results of DT applied to the data shown in Fig. 2. The locations and directions of the dipoles of P22 and P47 are superimposed on MRI images of stereotaxic sections of the brain in which coronal planes in A, B, and D correspond to a, b, and d in C. The estimated dipoles in the 19–24 ms latency range, concurrent with P22, were located in the posterior central gyrus, SI area (Fig. 5A, C, D). In the 45–55 ms latency range, concurrent with P47, dipoles were located around the superior parietal lobule (SPL) (areas 5 and 7) (Fig. 5B, C, D). These current generators were observed in the other 14 subjects in the same way; it first appeared at the SI, then moved to the areas 5 and 7.

Estimated dipoles generating cortical SEPs superimposed on a surface image created by magnetic resonance scans. Location of each dipole base is indicated by a filled circle, and direction of the dipole is indicated by projection of the line. The dipoles estimated at the latencies indicated by P22 and P47 in Fig. 2 b were superimposed based on [the] X and Y coordinates of the same subject. The dotted lines (a), (b), (d) in the horizontal plane (C) correspond to the MRI slices in (A), (B), and (D), respectively. The dipolarity was 96.3% in this subject

The above data (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5) indicated examples of the data derived from a single subject in 10-Hz electrical stimulation. The data from each subject were analyzed individually using the realistic head models so that the original 3-D coordinates were preserved. Furthermore we analyzed the group-averaged EEG data. Figure 6A showed such group-averaged SEPs. The results were essentially similar to those in Fig. 2b; positivity was observed around the contralateral somatosensory cortex at latency of 22 and 47 ms. Figure 6B shows the CSD maps at the latency of 22 (a), 47 (b), and 100 (c) ms indicated in Fig. 6A. CSD increased in the contralateral (left) parietal area not only at the latency of P22 (Ba; 22 ms), but also at the latency of P47 (Bb: 47 ms), and finally disappeared at 100 ms latency (Bc; 100 ms). Consistent with the data in the single subject (Fig. 4), CSD also increased in the ipsilateral parietal area at P47 (Bb; 47 ms) in the magnified calibration, although its intensity was much lower than that in the contralateral parietal area. Figure 6C indicates reliability of SEP waveforms across the three stimulation frequencies. Statistical analyses by one-way repeated measures ANOVA indicated that there were no significant differences in the amplitudes of P22 [F(2,24) = 2.257, P > 0.05], nor in the latencies of P22 [F(2,24) = 3.083, P > 0.05], This indicated that the SEPs were stable regardless of stimulation frequencies.

Group-averaged SEP data when 10-Hz stimulation was applied. A SEPs recorded from the 32 electrodes. GFP, global field power. Other descriptions as for Fig. 2. B EEG data (SEPs) shown in (A) were subjected to CSD transformation. The data were shown using two different calibrations since the CSD peaks in the ipsilateral parietal cortex were so small that magnified calibration was used. C Comparison of the amplitudes and peak latencies of P22. There were no significant differences in these parameters among the three stimulus frequencies

It is noted that the EEG data in Fig. 6A, B were automatically averaged based on position correspondence on the head cap. Figure 7 shows comparison of CSD amplitudes in the parietal cortex among the three different latencies (0, 22, and 47 ms). In Fig. 7, the CSD data were firstly computed using the individual data in each subject. Then, the data were averaged based on the anatomical correspondence by 3-D MRI data. Electrodes in the contralateral SI were determined based the locations of the dipole of P22; the electrodes closest to the dipoles were selected. In the ipsilateral SI area, the electrodes that were located in the postcentral gyrus just posterior to the ipsilateral motor hand area in the precentral gyrus (i.e., knob-like area) (Yousry et al. 1997) were selected. Usually two or three electrodes were located in the SPL. The electrodes closest to the center of the right and left SPL were selected. In the contralateral SI area, there were significant differences in the CSD amplitudes [one-way repeated measures ANOVA; F(2, 24) = 13.62, P < 0.05]. Post hoc tests indicated that the CSD amplitudes at 22 and 47 ms were significantly larger than that at 0 ms (Fisher’s LSD test, P < 0.01). On the other hand, there were no significant differences in the CSD amplitudes among the 3 latencies in the ipsilateral SI area [one-way repeated measures ANOVA; F(2, 24) = 1.391, P > 0.05]. In the contralateral SPL, there were significant differences in the CSD amplitudes among the 3 latencies [one-way repeated measures ANOVA; F(2, 24) = 4.911, P < 0.05]. Post hoc tests indicated that the CSD amplitudes at 47 ms were significantly larger than that at 0 ms (Fisher’s LSD test, P < 0.05). Furthermore, the CSD amplitudes tended to be larger at 22 ms than at 0 ms (Fisher’s LSD test, P < 0.10). In the ipsilateral SPL, there were significant differences in the CSD amplitudes among the three latencies [one-way repeated measures ANOVA; F(2, 24) = 30.62, P < 0.01]. Post hoc tests indicated that the CSD amplitudes at 47 ms were significantly larger than those at 0 and 22 ms (Fisher’s LSD test, P < 0.01). These results are consistent with the typical data derived from a single subject shown in Fig. 4.

Comparison of the CSD amplitudes in the parietal cortex among three different latencies (0, 22, 47 ms). Cont SI area, contralateral SI area; Cont SPL, contralateral superior parietal lobule; Ipsi SI area, ipsilateral SI area; Ipsi SPL, ipsilateral superior parietal lobule. **, *, #, Significant difference by P < 0.01, P < 0.05, P < 0.01, respectively

Analyses of Raw fNIRS Data

The NIRS data were summed and averaged in alignment with the onset of each block over 90 s [10 s before electrical stimulation (control), 30 s during stimulation, and 50 s after stimulation]. Of the data collected from the 15 subjects with reliable EEG recording, the NIRS data from two subjects were further discarded in some of the NIRS data analyses since data from NIRS channels other than the contralateral SI areas were contaminated with motion artifacts. Data only from the 21 NIRS channels are shown in Fig. 8. Changes in Oxy-Hb and Total-Hb strongly increased during electrical stimulation at the NIRS channel on the contralateral SI area [Ch9 (L)]. The mean peak latency of changes in Oxy-Hb concentration was 6.38 ± 0.54 s in the contralateral SI area (n = 15). It is noted that, in the ipsilateral parietal association cortices (e.g., Ch 12, 14, 16), changes in Oxy-Hb and Total-Hb also increased, but more slowly and less strongly than in the contralateral SI area. Similar hemodynamic responses were detected in all 13 subjects in the contralateral SI area. Figure 9 indicates group-averaged NIRS data. The data in the anatomically corresponding NIRS channels were averaged across the subjects. Changes in Oxy-Hb and Total-Hb strongly increased during electrical stimulation at the contralateral SI area, contralateral SPL, and ipsilateral SPL, but not at the ipsilateral SI area.

Examples of NIRS records in response to 10-Hz electrical stimulation of the right median nerve using the same subject as in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5. Red, green, and blue lines indicate changes in Oxy-Hb, Total-Hb, and Deoxy-Hb, respectively. Changes in Oxy-Hb rapidly increased at channel 9 around the contralateral SI. Arrows indicate onset of the stimuli

Group-averaged NIRS records in the contralateral (A) and ipsilateral (B) parietal cortices in response to 10-Hz electrical stimulation of the right median nerve using the all subjects. Other descriptions as for Fig. 8

Figure 10 shows a stimulus–response relationship at the NIRS channels with the maximum responses (changes in Oxy-Hb concentration) in the contralateral SI area. One-way ANOVA indicated a significant effect of stimulus frequency [F(2, 28) = 12.358, P < 0.001] (n = 15). Post hoc tests indicated that mean hemodynamic responses were larger in 10 than 2 Hz, and those were larger in 5 than in 2 Hz (Bonferroni test, P < 0.05).

Figures 3b and 11 show topographic brain maps of hemodynamic responses (changes in Oxy-Hb) from 0 to 15 s after onset of the stimulation block based on the data shown in Fig. 8. Hemodynamic responses increased only around the contralateral SI area 5 s after stimulation (Figs. 3b, 11B). Then, in addition to responses at the contralateral SI area, responses at the bilateral somatosensory association cortices located more posterior to the SI area increased from 10 to 15 s after electrical stimulation (Fig. 11C, D).

Statistical Assessment of Hemodynamic Responses

Hemodynamic responses noted in the above section were statistically assessed by GLM using a boxcar design with 6-s peak delay. Since 10-Hz stimulation evoked the most prominent responses as shown in Fig. 10, we analyzed the data of Oxy-Hb from the 15 subjects when 10-Hz stimulation was applied. Figure 12 shows the results (significant channels and T maps, respectively) by GLM analysis with 0- to 15-s onset delay. When onset delay was set at 0 s (A), T values at the contralateral SI were higher. Within the parietal lobe, significant channels were observed mainly in the contralateral parietal lobe (A) with 0-s onset delay.

Results of GLM analysis of the data shown in Fig. 8. A–D(a) Two-value maps indicating the NIRS channels with significant changes at different onset delays (OD). A–D(b) T value maps for different onset delays (OD). Note that the left SI area was activated at 0-s onset delay, and that the bilateral parietal lobes were activated at longer onset delays

When onset delay was increased to 5 and 10 s, hemodynamic responses became more strongly significant in the ipsilateral somatosensory association cortices (Bb, Cb). Consistent with these changes, the number of significant channels gradually increased in the ipsilateral somatosensory association cortices with 5 and 10 s onset delay (Ba, Ca), compared with those without onset delay (Aa). When onset delay was increased to 15 s, significant hemodynamic responses were confined to the ipsilateral somatosensory association cortices (D). On the other hand, T values in the contralateral SI area gradually became smaller with increased onset delay. However, it should be noted that T values denote only statistical significance, but not activity strength.

The temporal features of significant hemodynamic responses shown in Figs. 11 and 12 suggest that the number of NIRS channels with statistically significant hemodynamic responses gradually increased in the ipsilateral somatosensory association cortex with longer onset delay. Figure 13 shows the mean number of significant channels in the contralateral (left) and ipsilateral (right) parietal lobes of the 13 subjects for each onset delay. Analysis by two-way ANOVA with two factors (side × onset delay) indicated that there was a significant main effect of onset delay [F(3, 72) = 4.687, P < 0.01], and a significant interaction between side and onset delay [F(3, 72) = 12.011, P < 0.001]. The following subsidiary one-way ANOVA of the data in the contralateral parietal lobe indicated that there was a significant main effect of onset delay [F(3, 36) = 10.657, P < 0.001]. Post hoc comparisons indicated that the mean number of significant channels in 15-s onset delay was significantly smaller than those in 0- and 5-s onset delays, and that the mean number of significant channels in 10-s onset delay was significantly smaller than that in 5-s onset delay in the contralateral parietal lobe (Bonferroni tests, P < 0.05). Subsidiary one-way ANOVA of the data in the ipsilateral parietal lobe indicated a significant main effect of onset delay [F(3, 36) = 5.034, P < 0.01]. Post hoc comparisons indicated that the mean number of significant channels in 0-s onset delay was significantly smaller than those in 5- and 10-s onset delay in the ipsilateral parietal lobe (Bonferroni tests, P < 0.05).

Statistical comparison of the number of significant NIRS channels in the parietal cortex with different onset delays. Cont parietal Cx, contralateral (left) parietal cortex; Ipsi parietal Cx, ipsilateral (right) parietal cortex. (a) Significant difference between the contralateral and ipsilateral parietal lobes at 0-, 10- and 15-s onset delays (test of simple main effect, P < 0.05); (b) significant difference from 5- and 10-s onset delays within the ipsilateral parietal lobe (Bonferroni test, P < 0.05); (c) significant difference from 5-s onset delay within the contralateral parietal lobe (Bonferroni test, P < 0.05); (d) significant difference from 5- and 10-s onset delays within the contralateral parietal lobe (Bonferroni test, P < 0.05)

The above data in Fig. 13 indicated differences in temporal activation patterns between the contralateral and ipsilateral parietal lobes. Direct comparisons of the mean number of significant channels between the contralateral and ipsilateral parietal lobes in each onset delay revealed that the mean number of significant channels was significantly larger in the ipsilateral parietal lobe than the contralateral parietal lobe in 10- and 15-s onset delays [F(1, 24) = 5.484, and 14.678; P < 0.05, and 0.001, respectively] (tests for simple main effect), and was significantly larger in the contralateral parietal lobe than in the ipsilateral parietal lobe for 0-s onset delay [F(1, 24) = 4.611; P < 0.05] (tests for simple main effect). These results indicated that hemodynamic responses patterns gradually changed; hemodynamic responses initially appeared in the contralateral SI area, followed by the bilateral parietal lobes, and finally the ipsilateral parietal lobe.

Statistical Comparison of T Values with Different Onset Delay

To confirm the validity of introducing onset delay instead of a longer peak delay, T values in the GLM analysis were calculated in the contralateral SI area and bilateral superior parietal lobule (SPL) using all 13 subjects when either onset delay (i.e., 0, 5, 10, 15 sec) or peak delay (i.e., 6, 11, 16, 21 sec) were changed.

Figure 14A shows the four points where T values were calculated. NIRS channels in the contralateral SI were determined based the locations of the dipole of P22; the NIRS channels closest to the dipoles were selected. In the ipsilateral SI area, the NIRS channels that were located in the postcentral gyrus just posterior to the ipsilateral motor hand area in the precentral gyrus (i.e., knob-like area) (Yousry et al. 1997) were selected. Two or three NIRS channels were located in the SPL. The NIRS channels closest to the center of the right and left SPL were selected. Figure 14B shows the mean T values at each point when these parameters were changed. Filled symbols indicate the data when onset delay was manipulated while peak delay was constant (6 s). Statistical analysis of these data by two-way ANOVA with ‘area’ and ‘onset delay’ as the two factors indicated that there were significant main effects of area [F(3, 48) = 4.598, P < 0.01]and onset delay [F(3, 144) = 7.626, P < 0.001], and a significant interaction between area and onset delay [F(9, 144) = 2.877, P < 0.01].

Comparison of T values with different onset delays and peak delays in GLM analysis of hemodynamic responses. A Location of NIRS channels analyzed in (B). Cont, contralateral; Ipsi, ipsilateral. B Averaged T values (n = 13) when onset delay (OD, thin solid lines) or peak delay (PD, thin dotted lines) was set at indicated time. Thick dotted line indicates a significant level (T value = 3.0) in GLM analysis. a Significant difference from T values with OD = 0, 5, and 10 (Bonferroni test, P < 0.05); b significant difference from T values with OD = 0, 5, and 10 (Bonferroni test, P < 0.05)

Subsidiary one-way ANOVA of the data in the contralateral SI area with different onset delays and constant (6 s) peak delay indicated that there was a significant main effect of onset delay [F(3, 36) = 10.052, P < 0.001] (filled triangles). Post hoc comparison indicated that the mean T value with 15-s onset delay was significantly smaller than those with 0-, 5- and 10-s onset delay (Bonferroni test, P < 0.05). Furthermore, subsidiary one-way ANOVA of the data in different areas with 0-s onset delay indicated a significant main effect of area [F(3, 48) = 5.299, P < 0.01]. Post-hoc comparison indicated that the mean T value with 0-s onset delay in the contralateral SI area was larger than those in the ipsilateral SI area and bilateral SPL (Bonferroni test, P < 0.05). Thus, mean T values were higher in the contralateral SI area than in the other areas for 0-s onset delay, while T values decreased with longer onset delays and decreased below the level of significance for 15-s onset delay.

In the contralateral SPL, there were also significant differences in T values among the different onset delays with constant 6-s peak delay [one-way ANOVA; F(3, 36) = 6.932, P < 0.001] (filled diamonds). Post hoc comparison indicated that T values with 15-s onset delay were significantly smaller than those with 5- and 10-s onset delay (Bonferroni test, P < 0.05). In the ipsilateral SPL, there were no significant differences in T values among the different onset delays with 6-s peak delay [one-way ANOVA; F(3, 36) = 1.215, P < 0.05] (filled squares). However, when the data were compared by paired t-test, the mean T value with 5-s onset delay was larger than that with 0 s, and the mean T value with 10-s onset delay was larger than that with 15 s (paired t test, P < 0.05). Furthermore, mean T values reached the significant level (3.0) only when onset delay was 5 and 10 s. In the ipsilateral SI area there were no significant differences in T values among the different onset delays with constant 6-s peak delay [one-way ANOVA; F(3, 36) = 0.375, P > 0.05] (filled circles). Finally, it is noted that T values in all areas decreased below the level of significance for 15-s onset delay.

These patterns of changes in T values with different onset delays were similar to those in CSD and those in previous MEG studies (see “Discussion”). On the other hand, changes in peak delay did not reveal these dynamic changes (Fig. 14B, open symbols). Statistical analysis of these data by two-way ANOVA with ‘area’ and ‘peak delay’ as the two factors indicated that there was a significant main effect of area [F(3, 48) = 5.764, P < 0.01], but no significant main effect of peak delay [F(3, 144) = 1.813, P > 0.05], nor significant interaction between area and peak delay [F(9, 144) = 1.522, P > 0.05]. These results suggest that manipulation of onset delay is more appropriate to represent temporal changes in hemodynamic responses in the somatosensory cortex, which are similar to those in neurophysiological data.

Correlation Between Neuronal and Hemodynamic Responses

To investigate neuro-hemodynamic relationships, the 3-D distance between the dipoles of P22 and the NIRS points with maximum peak Oxy-Hb responses was analyzed. Figure 15 shows the distribution of the dipoles of P22 and NIRS points with the maximum hemodynamic responses. Locations of the dipoles and NIRS points coincided. Three-D distance ranged from 1.8 to 14.7 mm (6.72 ± 0.87) (n = 15). The distance was less than 10 mm except in one subject. These results suggested that Oxy-Hb hemodynamic responses were induced by electrical activity of the dipoles in the SI area.

This possibility was directly tested by comparing distributions of CSD at P22 and hemodynamic responses. Figure 16 shows an example of such comparison in subject No. 6. In this subject, spatial correlation between the CSD map and NIRS distributions was 0.838 (P < 0.001). The same significant results were observed in all 13 subjects (P < 0.05). These results suggest that synaptic activity underlying the dipoles of P22 induced hemodynamic responses. These results were consistent with previous studies showing that neuronal activities induced hemodynamic responses with similar latency (see Discussion).

Discussion

Neuro-Hemodynamic Relationships

Previous studies have reported that fMRI or BOLD signals are sensitive to changes in the small venous vessels induced by neural activity, while NIRS is more sensitive to those at the capillary level (Yamamoto and Kato 2002). However, there has been no standard statistical method to correlate hemodynamic responses measured by NIRS to neural activity. Previous studies analyzed NIRS data by averaging raw data in alignment with specific events or tasks; these averaged data synchronized to events were evaluated as hemodynamic responses (Hoshi and Tamura 1993; Kato et al. 1993; Villringer et al. 1993). Other studies have analyzed the data by GLM (Schroeter et al. 2004; Koch et al. 2006; Plichta et al. 2006), noise elimination (Katsura et al. 2006), and wavelet transform (Kojima et al. 2005). We statistically assessed the data using GLM with a box-car design matrix convoluted with Gaussian function instead of a pure box-car function since a previous fMRI study reported that the best compromise between goodness-of-fit and the number of model parameters was found with the Gaussian function (Rajapakse et al. 1998). Furthermore, since the NIRS system does not interfere with EEGs at all and EEGs have high temporal resolution, we simultaneously recorded fNIRS and EEGs to correlate hemodynamic responses to neural activity.

The present results indicated a significant neuro-hemodynamic coupling in the parietal lobe. First, the contralateral SI area displayed significantly higher T values than other areas in the GLM analysis (7.36 ± 0.40), consistent with previous neurophysiological studies (Arezzo et al. 1979, 1981; Allison et al. 1989a, b; Nishijo et al. 1994; Hayashi et al. 1995a, b). Second, changes in Oxy-Hb concentration were stronger with higher-frequency electrical stimulation, as in previous studies (Tanosaki et al. 2001, 2003). However, Sheth et al. (2004) reported that lower-frequency somatosensory stimulation elicited stronger hemodynamic responses measured by intrinsic light optical imaging using anesthetized animals. These differences in hemodynamic responses might be ascribed to the differences in usage of anesthetics and the subjects between these studies. Third, NIRS channels with maximum peak responses were located close to the dipole sites of P22; the mean distance was 6.72 mm. Fourth, CSD maps of the latency of P22 and NIRS hemodynamic topographies were significantly correlated. Sources of CSD are supposed to be located in the cortex (Srinivasan 2005). Consistent with the present results, previous studies reported that BOLD responses could be estimated from cortical current density distribution in simultaneous fMRI and EEG recording (Liu and He 2008; Minati et al. 2008). These results strongly suggest that the present GLM system using simultaneous NIRS and EEG recording could assess neuro-hemodynamic coupling in the parietal cortex.

Sequential Activation in the Parietal Cortex

There have been extensive NIRS studies on primary hemodynamic responses using various tasks, but few NIRS studies on secondary hemodynamic responses. Previous fMRI studies suggested that sequential hemodynamic changes in the temporal lobe were detected on the order of seconds in humans by estimating ‘lag time’ (‘peak delay’ in the present study) of Gaussian function in each activated area (Kruggel and von Cramon 1999), and that certain brain areas revealed delayed hemodynamic lags (‘onset delay’ in the present study) relative to other brain areas with the magnitude of that delay falling within the order of seconds (Schacter et al. 1997; Buckner et al. 1996, 1998; Bagshaw et al. 2004; Gotman et al. 2005). In the present study, we introduced onset delay instead of manipulation of peak delay, and suggest that onset delay better accounts for sequential activation in the parietal cortex (see below in detail).

Dipole tracing analysis indicated sequential activation in the parietal cortex; dipoles moved from the contralateral SI area to the contralateral superior parietal lobule around area 5. These results were consistent with a previous neurophysiological study using anesthetized monkeys (Hayashi et al. 1995a b). Furthermore, the averaged raw NIRS data indicated that Oxy-Hb increased in the ipsilateral somatosensory association cortices located posterior to the SI area. The analyses by ‘onset delay’ indicated that Oxy-Hb increased with a longer onset delay in the ipsilateral somatosensory cortices. Consistent with the present results indicating ipsilateral hemodynamic responses, a human neurophysiological study by direct cortical recording reported SEPs in the ipsilateral somatomotor areas (areas 4, 1, 2, and 7) with longer response latency (Allison et al. 1989a, b; Noachtar et al. 1997; Kanno et al. 2003), and suggested transcallosal inputs to these areas from the contralateral SI (Allison et al. 1989a, b). An fMRI study reported an activity increase in ipsilateral area 2, and suggested that the ipsilateral responses were mediated through transcallosal inputs (Hlushchuk and Hari 2006). An optical intrinsic signal imaging study in monkeys also reported activity in the ipsilateral SI area, and suggested top-down inputs from the higher-level processing areas such as the SII (Tommerdahl et al. 2006). The above studies reported that the latency of ipsilateral evoked responses to electrical median nerve stimulation was longer than that of contralateral evoked responses (see a review by Sutherland 2006), consistent with the present ‘onset delay’ analyses. These activation patterns were consistent with the fact in the present study that the mean number of significant channels in the ipsilateral parietal lobe gradually increased while that in the contralateral parietal lobe gradually decreased (Fig. 13).

In the present study, dipoles were not estimated in the ipsilateral parietal cortex although positive current sources were recorded from the ipsilateral parietal cortex. This failure to detect ipsilateral dipoles might be ascribed to considerably low amplitudes of SEPs in the ipsilateral somatosensory cortex consistent with a previous study (Noachtar et al. 1997), since imbalance in potential amplitudes between the two hemispheres resulted in estimation failure of dipoles in the hemisphere with low amplitudes (Ikeda et al. 1998). Furthermore, the NIRS channels in the ipsilateral SI area did not display significant T values in the present study (Fig. 14). Heterogeneity of hemodynamic responses within the ipsilateral somatomotor cortex has been reported; ipsilateral area 3b as well as the bilateral MI areas were deactivated while ipsilateral area 2 was activated during tactile finger stimulation (Hlushchuk and Hari, 2006). Summation of both the activated and deactivated hemodynamic responses in the NIRS channels of the SI area might result in non-significant hemodynamic responses in the ipsilateral SI area.

In conclusion, the present results suggest that simultaneous recording of NIRS and EEGs is useful for functional brain mapping. Especially, analyses using onset delay might be useful to investigate sequential hemodynamic responses in the parietal cortex. Further studies are required to test this approach in the other brain areas.

References

Allison T, McCarthy G, Wood CC, Darcey TM, Spencer DD, Williamson PD (1989a) Human cortical potentials evoked by stimulation of the median nerve. 1. Cytoarchitectonic areas generation short-lasting activity. J Neurophysiol 62:694–710

Allison T, McCarthy G, Wood CC, Williamson D, Spencer DD (1989b) Human cortical potentials evoked by stimulation of the median nerve. I. Cytoarchitectonic areas generating long-latency activity. J Neurophysiol 62:711–722

Arezzo J, Legatt AD, Vaughan HG Jr (1979) Topography and intracranial sources of somatosensory evoked potentials in the monkey. I. Early components. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 46:155–172

Arezzo JC, Vaughan HG Jr, Legatt AD (1981) Topography and intracranial sources of somatosensory evoked potentials in the monkey. II. Cortical components. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 51:1–18

Arthurs OJ, Williams EJ, Carpenter TA, Pickard JD, Boniface SJ (2000) Linear coupling between functional magnetic resonance imaging and evoked potential amplitude in human somatosensory cortex. Neuroscience 101:803–806

Backes WH, Mess WH, van Kramen-Mastenbroek V, Reulen JPH (2000) Somatosensory cortex responses to median nerve stimulation: fMRI effects of current amplitude and selective attention. Clin Neurophysiol 111:1738–1744

Bagshaw AP, Agha Khani Y, Bénar CG, Kobayashi E, Hawco C, Dubeau F, Pike GB, Gotman J (2004) EEG-fMRI of focal epileptic spikes: analysis with multiple haemodynamic functions and comparison with gadolinium-enhanced MR angiograms. Hum Brain Mapp 22:179–192

Banados M, Teitelboim C, Zanelli J (1994) Black hole entropy and the dimensional continuation of the Gauss-Bonnet theorem. Phys Rev Lett 14:957–960

Buckner RL, Bandettini PA, O’Craven KM, Savoy RL, Petersen SE, Raichle ME, Rosen BR (1996) Detection of cortical activation during averaged single trials of a cognitive task using functional magnetic resonance imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:14878–14883

Buckner RL, Koutstaal W, Schacter DL, Dale AM, Rotte M, Rosen BR (1998) Functional-anatomic study of episodic retrieval. II. Selective averaging of event-related fMRI trials to test the retrieval success hypothesis. NeuroImage 7:163–175

Chance B, Zhuang Z, UnAh C, Alter C, Lipton L (1993) Cognition-activated low-frequency modulation to light absorption in human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:3770–3774

Chen Y, Tailor DR, Intes X, Chance B (2003) Correlation between near-infrared spectroscopy and magnetic resonance imaging of rat brain oxygenation modulation. Phys Med Biol 48:417–427

Cummings FW (2001) The interaction of surface geometry with morphogens. J Theor Biol 212:303–313

Devor A, Dunn AK, Andersann ML, Ulbert I, Boas DA, Dale AM (2003) Coupling of total hemoglobin concentration, oxygenation, and neural activity in rat somatosensory cortex. Neuron 39:353–359

Duncan A, Meek JH, Clemence M, Elwell CE, Fallon P, Tyszczuk L, Cope M, Delpy DT (1996) Measurement of cranial optical path length as a function of age using phase resolved near infrared spectroscopy. Periatr Res 39:889–894

Endo S, Hayashi N, Takaku A, Ono T (1997) Preoperative simulation and intraoperative navigation with three-dimensional functional images. In: Szabo Z, Lewis JE, Fantini GA, Savalgi RS (eds) Surgical Technology International VI (STI VI). Universal Medical Press, San Francisco, pp 320–326

Fox PT, Raichle ME (1986) Focal physiological uncoupling of cerebral blood flow and oxidative metabolism during somatosensory simulation in human subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 83:1140–1144

Fox PT, Raichle ME, Mintun MA, Dence C (1988) Nonoxidative glucose consumption during focal physiologic neural activity. Science 241:462–464

Fukui Y, Ajichi Y, Okada E (2003) Monte Carlo prediction of near-infrared light propagation in realistic adult and neonatal head models. Appl Opt 42:2881–2887

Gerrits RJ, Stein EA, Greene AS (1998) Blood flow increases linearly in rat somatosensory cortex with increased whisker movement frequency. Brain Res 783:151–157

Giard MH, Perrin F, Pernier J, Bouchet P (1990) Brain generators implicated in the processing of auditory stimulus deviance: a topographic event-related potential study. Psychophysiology 27:627–640

Gotman J, Grova C, Baqshaw A, Kobayashi E, Aqhakhani Y, Dubeau F (2005) Generalized epileptic discharges show thalamocortical activation and suspension of the default state of the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:15236–15240

Gratton G, Coles MG, Donchin E (1983) A new method for off-line removal of ocular artifact. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 55:468–484

Hayashi N, Endo S, Kurimoto M, Nishijo H, Ono T, Takaku A (1995a) Functional image-guided neurosurgical simulation system using computerized three-dimensional graphics and dipole tracing. Neurosurgery 37:695–703

Hayashi N, Nishijo H, Ono T, Endo S, Tabuchi E (1995b) Generators of somatosensory evoked potentials investigated by dipole tracing in the monkey. Neuroscience 68:323–338

He B, Musha T, Okamoto Y, Homma S (1987) Electric dipole tracing in the human brain by means of the boundary element method and its accuracy. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 34:406–414

Hess A, Stiller D, Kaulisch T, Heil P, Scheich H (2000) New insights into the hemodynamic blood oxygenation level-dependent response through combination of functional magnetic resonance imaging and optical recording in gerbil barrel cortex. J Neurosci 20:3328–3338

Hlushchuk Y, Hari R (2006) Transient suppression of ipsilateral primary somatosensory cortex during tactile finger stimulation. J Neurosci 26:5819–5824

Hock C, Villringer K, Muller-Spahn F, Wenzel R, Heekeren H, Schuh-Hofer S, Hofmann M, Minoshima S, Schwaiger M, Dirnagl U, Villringer A (1997) Decrease in parietal cerebral hemoglobin oxygenation during performance of a verbal fluency task in patients with Alzheimer’s disease monitored by means of near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS)-correlation with simultaneous rCBF-PET measurements. Brain Res 755:293–303

Homma S, Musha T, Nakajima Y, Okamoto Y, Blom S, Flink R, Hagbarth KE, Mostrom U (1994) Localization of electric current sources in the human brain estimated by the dipole tracing method of the scalp-skull-brain (SSB) head model. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 91:374–382

Hoshi S (2003) Functional near-infrared optical imaging: utility and limitations in human brain mapping. Psychophysiology 40:511–520

Hoshi Y, Tamura M (1993) Detection of dynamic changes in cerebral oxygenation coupled to neuronal function during mental work in human. Neurosci Lett 150:5–8

Hoshi Y, Oda I, Wada Y, Ito Y, Yamashita Y, Oda M, Ohta K, Yamada Y, Tamura M (2000) Visuospatial imagery is a fruitful strategy for the digit span backward task: a study with near-infrared optical tomography. Cogn Brain Res 9:339–342

Hoshi Y, Kobayashi N, Tamura M (2001) Interpretation of near-infrared spectroscopy signal: a study with a newly developed perfused rat brain model. J Appl Physiol 90:1657–1662

Huettel S (2004) Non-linearities in the blood-oxygenation-level dependent (BOLD) response measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 6:4413–4416

Huppert TJ, Hoge RD, Diamond SG, Franceschini MA, Boas DA (2006) A temporal comparison of BOLD, ASL and NIRS hemodynamic responses to motor stimuli in adult humans. NeuroImage 29:368–382

Ibanez V, Deiber MP, Sadato N, Toro C, Grisson J, Wood RP, Mazziotta JC, Hallett M (1995) Effects of stimulus rate on regional cerebral blood flow after median nerve stimulation. Brain 118:1339–1351

Ikeda H, Nishijo H, Miyamoto K, Tamura R, Endo S, Ono T (1998) Generators of visual evoked potentials investigated by dipole tracing in the human occipital cortex. Neuroscience 84:723–739

Jobsis FF (1977) Noninvasive infrared monitoring of cerebral and myocardial oxygen sufficiency and circulatory parameters. Science 198:1264–1267

Kampe KK, Jones RA, Auer DP (2000) Frequency dependence of the functional MRI response after electric median nerve stimulation. Hum Brain Mapp 9:106–114

Kanno A, Nakasato N, Hatanaka K, Yoshimoto T (2003) Ipsilateral area 3b responses to median nerve somatosensory stimulation. NeuroImage 18:169–177

Kato T, Kamei A, Takashima S, Ozaki T (1993) Human visual cortical function during photic stimulation monitoring by means of near-infrared spectroscopy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 13:516–520

Katsura T, Tanaka N, Obata A, Sato H, Maki A (2006) Quantitative evaluation of interrelations between spontaneous low frequency oscillations in cerebral hemodynamics and systemic cardiovascular dynamics. NeuroImage 31:1592–1600

Kleinschmidt A, Obrig H, Requardt M, Merboldt KD, Dirnagl U, Villringer A, Frahm J (1996) Simultaneous recording of cerebral blood oxygenation changes during human brain activation by magnetic resonance imaging and near-infrared spectroscopy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 16:817–826

Koch SP, Steinbrink J, Villringer A, Obrig H (2006) Synchronization between background activity and visually evoked potential is not mirrored by focal hyperoxygenation: Implications for the interpretation of vascular brain imaging. J Neurosci 26:4940–4948

Kojima T, Tsunashima H, Shiozawa T, Takada H, Sakai T (2005) Measurement of train driver’s brain activity by functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). Opt Quant Electron 37:1319–1338

Kruggel F, von Cramon DY (1999) Temporal properties of the hemodynamic response in functional MRI. Hum Brain Mapp 8:259–271

Liu Z, He B (2008) fMRI-EEG integrated cortical source imaging by use of time-variant spatial constraints. NeuroImage 39:1198–1214

Longothetis NK, Pauls J, Augath M, Trinath T, Oeltermann A (2001) Neurophysiological investigation of the basis of the fMRI signal. Nature 412:150–157

Lorensen WE, Cline HE (1987) Marching cubes: a high resolution 3D surface construction algorithm. Proc. ACM SIGGRAPH’87 21:163–170

McCormick PW, Stewart M, Lewis G, Dujovny M, Ausman JI (1992) Intracerebral penetration of infrared light. Technical note. J Neurosurg 76:315–318

Mehagnoul-Schipper DJ, van der Kallen BF, Colier WN, van der Sluijs MC, van Erning LJ, Thijssen HO, Oeseburg B, Hoefnagels W, Jansen RW (2002) Simultaneous measurements of cerebral oxygenation changes during brain activation by near-infrared spectroscopy and functional magnetic resonance imaging in healthy young and elderly subjects. Human Brain Mapp 16:14–23

Metting van Rijin AC, Peper A, Grimbergen CA (1990) High-quality recording of bioelectric events. Part 1. Interference reduction, theory and practice. Med Biol Eng Comput 25:389–397

Minati L, Rosazza C, Zucca I, D’Incerti L, Scaioli V, Bruzzone MG (2008) Spatial correspondence between functional MRI (fMRI) activations and cortical current density maps of event-related potentials (ERP): a study with four tasks. Brain Topogr 21:112–127

Musha T, Okamoto Y (1999) Forward and inverse problems of EEG dipole localization. Crit Rev Biomed Eng 27:189–239

Nishijo H, Hayahi N, Fukuda M, Endo S, Musha T, Ono T (1994) Localization of dipole by boundary element method in three dimensional reconstructed monkey brain. Brain Res Bull 33:225–230

Noachtar S, Luder HO, Kinner DS, Kem G (1997) Ipsilateral median somatosensory evoked potentials recorded from human somatosensory cortex. Electroencephalogr Clin Neuroshysiol 104:189–198

Ogawa S, Menon RS, Tank DW, Kin SG, Merkle H, Ellermann JM, Ugurbil K (1993) Functional brain mapping by blood oxygenation level-dependent contrast magnetic resonance imaging. A comparison of signal characteristics with a biophysical model. Biophys J 64:803–812

Okamoto M, Dan H, Sakamoto K, Takeo K, Shimizu K, Kohno S, Oda I, Isobe S, Suzuki T, Kohyama K, Dan I (2004) Three-dimensional probabilistic anatomical cranio-cerebral correlation via the international 10–20 system oriented for transcranial functional brain mapping. NeuroImage 21:99–111

Plichta MM, Herrmann MJ, Baehne CG, Ehlis AC, Richter MM, Pauli P, Fallgatter AJ (2006) Event-related functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS): are the measurements reliable? NeuroImage 31:116–124

Pouratian N, Sicotte N, Rex D, Martin NA, Becker D, Cannestra AF, Toga AW (2002) Spatial/temporal correlation of BOLD and optical intrinsic signals in humans. Magn Reson Med 47:766–776

Puce A, Constable T, Luby ML, McCarthy G, Nobre AC, Spencer DD, Gore JC, Allison T (1995) Functional magnetic resonance imaging of sensory and motor cortex: comparison with electrophysiological location. J Neurosurg 83:262–270

Punwani SOR, Cooper CE, Amess P, Clemence M (1998) MRI measurements of cerebral deoxyhaemoglobin concentration [dHb]-correlation with near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS). NMR Biomed 11:281–289

Rajapakse JC, Kruqqel F, Maisoq JM, von Cramon DY (1998) Modeling hemodynamic response for analysis of functional MRI time-series. Hum Brain Mapp 6:283–300

Roche-Labarbe N, Wallois F, Ponchel E, Kongolo G, Grebe R (2007) Coupled oxygenation oscillation measured by NIRS and intermittent cerebral activation on EEG in premature infants. NeuroImage 36:718–727

Roy CS, Sherrington CS (1890) On the regulation of the blood-supply of the brain. J Physiol 11:85–108

Schacter DL, Buckner RL, Koutstaal W, Dale AM, Rosen BR (1997) Late onset of anterior prefrontal activity during true and false recognition: an event-related fMRI study. NeuroImage 6:259–269

Schroeter ML, Bucheler MM, Muller K, Uludaq K, Obriq H, Lohmann G, Tittqemeyer M, Villringer A, von Cramon DY (2004) Towards a standard analysis for functional near-infrared imaging. NeuroImage 21:283–290

Schroeter ML, Kupka T, Mildner T, Uludag K, von Cramon DY (2006) Investigating the post-stimulus undershoot of the BOLD signal—a simultaneous fMRI and fNIRS study. NeuroImage 30:349–358

Seiyama A, Hazeki O, Tamura M (1988) Noninvasive quantitative analysis of blood oxygenation in rat skeletal muscle. J Biochem (Tokyo) 103:419–424

Seiyama A, Seki J, Tanabe HC, Sase I, Takatsuki A, Miyauchi S, Eda H, Hayashi S, Imaruoka T, Iwakura T, Yanagida T (2004) Circulatory basis of fMRI signals: relationship between changes in the hemodynamic parameters and BOLD signal intensity. NeuroImage 21:1204–1214

Shepard D (1968) A two-dimensional interpolation function for irregularly-spaced data. In: Proceedings of the 23rd national conference ACM. ACM Press, New York, pp 517–524

Sheth SA, Nemoto M, Guiou M, Walker M, Puratian N, Toga AW (2004) Linear and nonlinear relationships between neuronal activity, oxygen metabolism, and hemodynamic responses. Neuron 42:347–355

Shibata T, Nishijo H, Tamura R, Miyamoto K, Eifuku S, Endo S, Ono T (2002) Generators of visual evoked potentials for faces and eyes in the human brain as determined by dipole localization. Brain Topogr 15:51–63

Siegel AM, Culver JP, Mandeville JB, Boas DA (2003) Temporal comparison of functional brain imaging with diffuse optical tomography and fMRI during rat forepaw stimulation. Phys Med Biol 48:1391–1403

Spiegel J, Tintera J, Gawehn J, Stoeter P, Treede RD (1999) Functional MRI of human primary somatosensory and motor cortex during median nerve stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol 110:47–52

Srinivasan H (2005) High-resolution EEG: theory and practice. In: Handy TC (ed) Event-related potentials. A methods handbook. The MIT Press, London, pp 167–188

Strangman G, Culver JP, Thompson JH, Boas DA (2002) A quantitative comparison of simultaneous BOLD fMRI and NIRS recordings during functional brain activation. NeuroImage 17:719–731

Sutherland MT (2006) The hand and the ipsilateral primary somatosensory cortex. J Neurosci 26:8217–8218

Takakura H, Umeno K, Tabuchi E, Hori E, Miyamoto K, Asao S, Watanabe Y, Ono T, Nishijo H (2003) Differential activation in the medial temporal lobe during a sound-sequence discrimination task across age in human subjects. Neuroscience 119:517–532

Tanosaki M, Hoshi Y, Iguchi Y, Oikawa Y, Oda I, Oda M (2001) Variation of temporal characteristics in human cerebral hemodynamic responses to electric median nerve stimulation: a near-infrared spectroscopic study. Neurosci Lett 316:75–78

Tanosaki M, Sato C, Shimada M, Iguchi Y, Hoshi Y (2003) Effect of stimulus frequency on human cerebral hemodynamic responses to electric median nerve stimulation: a near-infrared spectroscopic study. Neurosci Lett 352:1–4

Tommerdahl M, Simons SB, Chiu JS, Favorov O, Whitsel BL (2006) Ipsilateral input modifies the primary somatosensory cortex response to contralateral skin flutter. J Neurosci 26:5970–5977

Toronov V, Webb A, Choi JH, Wolf M, Michalos A, Gratton E, Heuber D (2001) Investigation of human brain hemodynamics by simultaneous near-infrared spectroscopy and functional magnetic resonance imaging. Med Phys 28:521–527

Toronov V, Webb A, Walker S, Gupta R, Choi JH, Gratton E, Hueber D, Webb A (2003) The roles of changes in deoxyhemoglobin concentration and regional cerebral blood volume in the fMRI BOLD signal. NeuroImage 19:1521–1531

Villringer A, Plank J, Hock C, Schleinkofer L, Dirnagl U (1993) Near-infrared spectroscopy(NIRS): a new tool to study hemodynamic changes during activation of brain function in human adults. Neurosci Lett 154:101–104

Wray S, Cope M, Delpy DT, Wyatt JS, Reynolds EO (1988) Characterization of the near infrared absorption spectra of cytochrome aa3 and haemoglobin for the non-invasive monitoring of cerebral oxygenation. Biochim Biophys Acta 30:184–192

Yamamoto Y, Kato T (2002) Paradoxical correlation between signal in functional magnetic resonance imaging and deoxygenated haemoglobin content in capillaries : a new theoretical explanation. Phys Med Biol 47:1121–1141

Yousry TA, Schmid UD, Alkadhi H, Schmidt D, Peraud A, Buettner A, Winkler P (1997) Localization of the motor hand area to a knob on the precentral gyrus. A new landmark. Brain 120:141–157

Acknowledgement

This study was supported partly by the JSPS Asian Core Program.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Takeuchi, M., Hori, E., Takamoto, K. et al. Brain Cortical Mapping by Simultaneous Recording of Functional Near Infrared Spectroscopy and Electroencephalograms from the Whole Brain During Right Median Nerve Stimulation. Brain Topogr 22, 197–214 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10548-009-0109-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10548-009-0109-2