Abstract

Introduced non-native fishes can cause considerable adverse impacts on freshwater ecosystems. The pumpkinseed Lepomis gibbosus, a North American centrarchid, is one of the most widely distributed non-native fishes in Europe, having established self-sustaining populations in at least 28 countries, including the U.K. where it is predicted to become invasive under warmer climate conditions. To predict the consequences of increased invasiveness, a field experiment was completed over a summer period using a Control comprising of an assemblage of native fishes of known starting abundance and a Treatment using the same assemblage but with elevated L. gibbosus densities. The trophic consequences of L. gibbosus invasion were assessed with stable isotope analysis and associated metrics including the isotopic niche, measured as standard ellipse area. The isotopic niches of native gudgeon Gobio gobio and roach Rutilus rutilus overlapped substantially with that of non-native L. gibbosus, and were also substantially reduced in size compared to ponds where L. gibbosus were absent. This suggests these native fishes shifted to a more specialized diet in L. gibbosus presence. Both of these native fishes also demonstrated a concomitant and significant reduction in their trophic position in L. gibbosus presence, with a significant decrease also evident in the somatic growth rate and body condition of G. gobio. Thus, there were marked changes detected in the isotopic ecology and growth rates of the native fish in the presence of non-native L. gibbosus. The implications of these results for present and future invaded pond communities are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Introduced non-native fishes can cause considerable adverse impacts on the structure and function of aquatic ecosystems, particularly in freshwaters, although the evidence is often circumstantial or speculative (e.g. Gozlan 2008; Gozlan et al. 2010). Predicting the introduced fishes that will establish invasive populations and impact recipient food webs and ecosystems thus remains a major ecological challenge (Copp et al. 2009; Tran et al. 2015). Determinants of invasion success include how the introduced species interacts trophically with the extant native species, such as whether they converge or diverge in resource use, with the intensity of these interactions influencing the ecological impacts that could subsequently develop (Jackson et al. 2012; Tran et al. 2015). Impacts can develop from, for example, alterations in the symmetry of competition between species (Kakareko et al. 2013) and predator–prey relationships (Woodford et al. 2005; Cucherousset et al. 2012). Consequently, quantifying the feeding relationships of introduced and native fishes is a fundamental component of assessing their ecological risk (Tran et al. 2015) and enables their influence on aspects of food web structure and ecosystem functioning to then be quantified (Gozlan et al. 2010).

Following an introduction of a non-native fish, ecological impacts often develop through their feeding interactions with extant fishes (Gozlan et al. 2010; Cucherousset et al. 2012). Ecological theory suggests the trophic consequences of introductions will vary according to the extent of their interactions. In systems where the food resources are not fully exploited, the introduced species can exploit these dietary niches, facilitating their establishment as it reduces their competitive interactions with native populations (Shea and Chesson 2002; Tran et al. 2015). Where niche partitioning is not possible, the niche variation hypothesis predicts that the increased competitive interactions between the species will result in diet constriction, leading to increased diet specialisation post-invasion (Van Valen 1965; Thomson 2004; Olsson et al. 2009). These outcomes were recently observed in invasive topmouth gudgeon Pseudorasbora parva populations in the U.K., where strong patterns of niche divergence and constriction were evident in invaded native fish communities (Jackson and Britton 2014; Tran et al. 2015). Alternatively, theory also suggests that larger trophic niches can result from increased resource competition, as the competing species exploit a wider dietary base to maintain their energetic requirements (Svanbäck and Bolnick 2007). Thus, the trophic consequences of fish invasions can be difficult to predict, particularly in the wild where there tends to be an absence of data in the pre-invaded state (Tran et al. 2015). The derivation of empirical data within robust experimental designs can therefore assist risk assessment processes by providing increased insights into the risks posed by specific species, as well as concomitantly testing aspects of relevant ecological theory (Copp et al. 2014).

The pumpkinseed Lepomis gibbosus is a North American sunfish (Centrarchidae) that has been introduced to, and established in, at least 28 countries across Europe and Asia Minor (Copp and Fox 2007), and also with established non-native populations in Brazil (e.g. Santos et al. 2012). Whilst not currently considered to be invasive at more northerly latitudes, including the U.K., L. gibbosus is predicted to become invasive under conditions of climate warming (Britton et al. 2010); this is expected to result in earlier reproduction (Zięba et al. 2010), enhanced recruitment (Zięba et al. 2015) and subsequent greater dispersal (Fobert et al. 2013). These traits are then anticipated to result in adverse impacts on native species and ecosystems (e.g. Angeler et al. 2002a, b; Van Kleef et al. 2008). There is also considerable potential for invasive populations to interact trophically with native fishes through their opportunistic omnivory that undergoes ontogenetic shifts, with a switch from feeding mainly on plankton as larvae to a diet consisting largely of benthic invertebrates as juveniles and adults (Rezsu and Specziár 2006), particularly chironomid larvae (Domínguez et al. 2002; Nikolova et al. 2008) and/or amphipods (García-Berthou and Moreno-Amich 2000). This is especially relevant to pond ecosystems, which are now known to support disproportionately high biodiversity (e.g. Williams et al. 2003). Predation on fish is also occasionally reported for larger (older) L. gibbosus in Europe, though in some cases this is limited to cannibalism (Guti et al. 1991; Copp et al. 2002, 2010) or predation on other non-native fish (e.g. eastern mosquitofish Gambusia holbrooki; Almeida et al. 2009). Notwithstanding, evidence of ecological impacts by invasive populations remains equivocal and whilst many studies report ecological impacts attributed to L. gibbosus, these often show correlations between relevant metrics rather than causality (e.g. Vilizzi et al. 2015). Similarly, L. gibbosus presence has been linked to declines in prey abundances, but without direct evidence of an interaction (e.g. García-Berthou and Moreno-Amich 2000).

Consequently, the aim of this study was to assess the ecological consequences of L. gibbosus introduction into ponds in a temperate region in northern Europe through assessment of their dietary interactions and trophic ecology using stable isotope analysis (SIA) in a field experimental approach. The specific objectives were to: (1) quantify how introduced L. gibbosus modified the trophic position (TP) and trophic niche size of the native fishes, and (2) identify any consequences for their growth rates and body condition. Note that the trophic niche was measured as the isotopic niche size and thus hereafter is referred to as the ‘isotopic niche’. Whilst the isotopic niche is closely related to the trophic niche, which is a sub-component of the ecological ‘niche’ (Copp 2008), and it is also influenced by factors including growth rate and metabolism (Jackson et al. 2011).

Materials and methods

This field experiments were undertaken in six artificial outdoor ponds, which are located in southern England and were constructed specifically for research on L. gibbosus reproduction, recruitment and impact assessments (Zięba et al. 2010, 2015; Fobert et al. 2011). Situated on the grounds of a commercial angling venue in an area exposed to natural light, all six ponds were 5 × 5 m, with a similar bathometry consisting of a shallow (0.2–0.5 m), 1-m wide shelf along one side, with all remaining area being ≈1.2 m deep (Fig. 1). The ponds were lined with reinforced rubberised plastic liner and enclosed at their banks by a shelf-like edge made of wooden planks, raised ≈30 cm above ground level. Each pond was fitted with anti-bird netting, which was elevated above the ponds on posts, as well as an identical water recirculation system, consisting of a fountain pump (P2500, Bladgon, U.K., with the maximum flow-through discharge of 2400 L h−1), which pumped water from the pond into a fibreglass cistern (0.2 m3) filled with Canterbury spar stone chips (as substratum for bacterial water filtration). An overflow pipe allowed water in the cistern to discharge back into the pond. A TinyTag “Aquatic 2” temperature logger (Gemini Data Loggers Ltd, U.K.) was placed in each pond for continuous recording of temperature. Any natural loss of water due to evaporation was replaced by gravel-filtered water taken from an adjacent pond.

The experimental design consisted of a Control and Treatment, each of three replicates. The Control consisted of a model native fish community in L. gibbosus absence that comprised of four species (Table 1): roach Rutilus rutilus (n = 10), rudd Scardinius erythrophthalmus (n = 9), tench Tinca tinca (n = 10) and gudgeon Gobio gobio (n = 10). The Treatment comprised of the same native fish community but differed with L. gibbosus being introduced. The number of L. gibbosus stocked into the Treatment ponds was 30, to provide a similar biomass to that of the native fishes and to simulate the relative numbers likely to be present in invaded pond as predicted will occur under future, warmer, climatic conditions (Fobert et al. 2013). All starting fish were mainly age 1+ years and <100 mm in length. With the exception of T. tinca that were sourced from aquaculture, all of the fish used in the experiment were available from the larger ponds used for angling on the site.

The Control and Treatment ponds were all set up initially on 18 March 2014, when the native fishes were introduced into each pond following measurement, under mild anaesthesia (5 ml L−1 of 2-phenoxyethanol). As cyprinid fishes, such as R. rutilus, are known to suffer elevated mortality rates following handling (e.g. Persson and Greenberg 1990), this was minimized by only measuring total length (TL; to the nearest mm) at the start of the experiment, with mass (in g) of individual fish estimated from published length–weight equations for the U.K. (Britton and Shepherd 2005). The experimental ponds were then left until mid June 2014 to allow the pond communities to establish, with L. gibbosus then released into the Treatment ponds. Several fishes were lost (most probably due to avian predators, as holes in the netting were found in mid June) and therefore additional native fishes were captured on 19 June from two adjacent angling ponds (A, B) and stocked into the experimental ponds on 20 June (Table 1), which was thus taken as the start date of the experiment, which ran until 25–26 September. Thus, the minimum time an individual fish was present in the ponds was 97 days. During these 97 days, the mean water temperature in each pond was at least 19.9 °C (cf. “Results” section). Estimates of stable isotope half-lives, and thus the extent of isotopic replacement in the experimental fish over 97 days at 20 °C, are provided by Thomas and Crowther (2015). For individual consumers with a starting mass of 1 g, their estimated half-life at 20 °C is 23 days for δ13C (4.2 half lives/94 % isotopic replacement) and 25 days for δ15N (3.9 half lives/93 % replacement). For individuals at 10 g, the estimated half-life at 20 °C is 36 days for δ13C (2.7 half lives/84 % replacement) and 38 days for δ15N (2.6 half lives/83 % replacement) (Thomas and Crowther 2015). Consumers are generally considered to have fully equilibrated to their food resources from 94 % isotopic replacement (i.e. 4 half lives; Hobson and Clark 1992). Thus, these estimates of Thomas and Crowther (2015) suggested that in the experiment, isotopic equilibrium was reached in the smaller fishes and was at least close to equilibrium in the larger fishes (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4). The experiment was terminated in late September, as water temperatures would then steadily decrease into October, reducing rates of fish growth and isotopic turnover (Busst and Britton 2016).

On 25 and 26 September, the ponds were drained down and the fish removed, counted, re-measured for TL (to 1 mm) and measured for mass (to 0.1 g), and a tissue sample (fin clip) was taken for SIA (fin clip) whilst under general anaesthesia (as above). Concomitantly, samples of putative prey resources were collected from each of the ponds for subsequent SIA (n = 3–9 of each per pond). Native fishes were returned to their adjacent angling ponds of origin, and all L. gibbosus were killed under Home Office licence due to their non-native status.

One day prior to the stocking of fish into the experimental ponds, and one day before the ponds were drained at the end of the experiment, the physical and chemical water characters were measured in each pond, including: conductivity (µS cm−1), dissolved oxygen (mg L−1), total nitrogen (mg L−1), total phosphorous (mg L−1), pH and water temperature (°C). Then, semi-quantitative samples were collected from each pond for macro-invertebrates (individuals per 5 min of sweeping) using an FBA pond net (mesh size = 900 microns). In the laboratory, the invertebrates were counted under macro- or microscopes, as appropriate. Macroinvertebrates were counted directly. The ‘relative abundance’ values for macroinvertebrates are effectively catch-per-unit-effort (of time) estimates. Fish TL and mass data at recovery were used to estimate body condition (i.e. plumpness) using Fulton’s condition factor (K = 100 × W ÷ TL3), where W is mass in g and TL given in cm. Comparisons among ponds (Control vs. Treatment) and among dates (stocking vs. recovery) for TL and mass were made with analysis of variance (ANOVA), and for Fulton’s body K among Control versus Treatment ponds at recovery using Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test.

Stable isotope analysis

The collected samples of primary interest for SIA were fish tissues and the macro-invertebrate samples as the fish putative prey resources. The macro-invertebrates were considered as important because many studies have revealed that these are the primary prey resources of the model fishes at the lengths introduced to the experimental ponds (e.g. Kennedy and Fitzmaurice 1972; Godinho et al. 1997). The macro-invertebrate species analysed were Chironomidae, Asellus aquaticus and Corixidae, as all were expected to contribute strongly to fish diet. These samples were oven dried to constant weight at 60 °C and analysed at the Cornell Isotope Laboratory, New York, USA. The samples were ground to powder and weighed precisely to ≈1000 µg in tin capsules and analysed on a Thermo Delta V isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) interfaced to a NC2500 elemental analyser (CE Elantach Inc., USA). Verification for accuracy was against internationally known reference materials, whose values are determined by the International Association of Atomic Energy (IAEA; Vienna, Austria), and calibrated against the primary reference scales for δ13C and δ15N (Cornell University Stable Isotope Laboratory 2015). The accuracy and precision of the sample runs was tested every 10 samples using a standard animal sample (mink). The overall standard deviation was 0.11 ‰ for δ15N and 0.09 for δ13C. Linearity correction accounted for differences in peak amplitudes between sample and reference gases (N2 or CO2). Analytical precision associated with the δ15N and δ13C sample runs estimated at 0.42 and 0.15 ‰, respectively. The initial data outputs were in the format of delta (δ) isotope ratios expressed per mille (‰). There was no lipid correction applied to the data as C:N ratios indicated very low lipid content and thus lipid extraction or normalization would have little effect on δ13C (Post et al. 2007).

The initial analyses of the stable isotope data of the fishes and macro-invertebrates involved constructing bi-plots of δ13C versus δ15N for each pond. Here, and in subsequent analyses, it was assumed that the fractionation factor between fin tissues and fish diet were constant between the species. Although some studies have indicated some variability in these fractionation factors between fish species generally (e.g. Tronquart et al. 2012; Busst et al. 2015), fractionation data were not available for all study fishes and hence this assumption was used. The mean coefficient of variation and range of δ13C and δ15N were calculated per species and pond. Whilst coefficients of variation (CV) and isotopic ranges per species were then compared between the treatments, it was apparent that there were some considerable differences in the isotopic data across the ponds, most notably between one of the replicates of the no-pumpkinseed Treatment and all other replicates (cf. “Results” section). Correspondingly, in order to be able to make comparisons between the isotopic data between the treatments and to test them statistically, the stable isotope data had to be corrected. This was completed as per Tran et al. (2015), where for δ15N, TP was calculated using TPi = [(δ15Ni − δ15Nbase)/3.4] + 2, where TPi is the TP of the individual fish, δ 15Ni is the isotopic ratio of that fish, δ15Nbase is the isotopic ratio of the primary consumers (i.e. the ‘baseline’ invertebrates), 3.4 is the fractionation between trophic levels and 2.0 is the TP of the baseline organism (Post 2002). Although the fractionation value of 3.4 was not specific to any of the fishes used in the study, it provided a consistent value in the calculations to result in TP data that were relative across the species. For δ13C, values were converted to δ13Ccorr using δ13Ci − δ13Cmeaninv/CRinv, where δ13Ccorr is the corrected carbon isotope ratio of the individual fish, δ13Ci is the uncorrected isotope ratio of that fish, δ13Cmeaninv is the mean invertebrate isotope ratio (the ‘baseline’ invertebrates) and CRinv is the invertebrate carbon range (δ13Cmax − δ13Cmin; Olsson et al. 2009).

In the recaptured fishes, there were only sufficient data in both the L. gibbosus (PS) and no-L. gibbosus (no-PS) treatments to analyse differences between the treatments in the corrected data of G. gobio and R. rutilus, but not T. tinca and S. erythrophthalmus (cf. “Results” section). The corrected stable isotope data were used in linear mixed models to test for differences in TP and Ccorr between L. gibbosus and the native fishes, and between the native fish in the two treatments. In all cases, the assumptions of normality of residuals and homoscedasticity were checked prior to testing, with the response variables log-transformed as necessary. The models were fitted with pond as a random effect. This avoided inflation of the residual degrees of freedom that would otherwise result if each fish were used as a true replicate in an experimental design consisting of two treatments with three replicates (Dossena et al. 2012; Tran et al. 2015). All models were fitted using restricted maximum likelihood to determine the parameter estimates. Differences in TPs and Ccorr by species were determined using estimated marginal means and multiple comparison post hoc analyses (general linear hypothesis test).

The corrected stable isotope data for L. gibbosus, G. gobio and R. rutilus in the PS and no-PS treatments were then used to calculate the standard ellipse area (SEA) for each species per treatment in the SIAR package (Jackson et al. 2011) in the R computing program (R Development Core Team 2014). Standard ellipse areas are bivariate measures of the distribution of individuals in trophic space. As each ellipse encloses ≈40 % of the data, they represent the core dietary breadth (so-called isotopic or trophic niche; hereafter referred to here as the isotopic niche) and thus reveal the typical resource use within a species or population (Jackson et al. 2011, 2012). Owing to variable sample sizes between the species (cf. “Results” section), a Bayesian estimate of SEA (SEAB) was used, determined by using a Markov chain Monte Carlo simulation with 104 iterations for each group (Jackson et al. 2011; R Development Core Team 2014; Tran et al. 2015). This generated 95 % confidence intervals around the SEAB estimates; where these confidence intervals did not overlap between comparator species or experimental treatments, the isotopic niches were interpreted as significantly different. The extent of the overlap between the SEAB values between the species was determined (%), with this representing the extent of their shared isotopic resources.

In the Results, where error around the mean is presented, it represents standard error unless otherwise stated.

Results

Water chemistry, invertebrate abundances and fish growth rates

There were only minor differences in water chemistry variables across the Control and Treatment ponds at the start and end of the experimental period (Table 2). Macro-invertebrates found in the experimental ponds included A. aquaticus, Baetis spp. Chironomidae, Corixidae juveniles, Oligochaeta, Pisidium sp., Simulidae and Tipulidae. Over the course of the experiments, mean macro-invertebrate relative abundances decreased by 5.2 ± 1.7 individuals (ind.) min−1 in the Control ponds and by 4.5 ± 0.6 ind. min−1 in the Treatment ponds.

At the time of fish stocking into the ponds (20 June 2014), there was no difference in the mean TLs of native fishes (R. rutilus, T. tinca, S. erythrophthalmus, G. gobio) among ponds overall, or for Control vs. Treatment ponds (Table 3). At the conclusion of the experiment, the numbers of fish recovered from the ponds was reduced from the original number released (Table 1), with no significant differences in TLs of R. rutilus, S. erythropthalmus or T. tinca among the Control and Treatment ponds at the end of the experiment (Table 4). Whereas, for G. gobio, the recovered individuals were of significantly greater mass and condition factor (K) in the Control than the Treatment ponds (Table 4). In terms of growth over the course of the experiment, all of the species increased in TL, up to 4× in some cases (Table 3), and in mass—in most cases significantly (Ps < 0.05; Table 4). Note that the changes in mass over the course of the experiment are given for heuristic purposes and must be viewed with caution because mass at stocking was estimated from TL but measured directly at recovery. Reproduction was apparent in one experimental pond each for T. tinca and L. gibbosus, whereas G. gobio spawned in three of the ponds (Table 5).

Stable isotope analyses

Stable isotope biplots per pond suggested that, with the exception of the larger-bodied L. gibbosus, the δ15N fractionation values between the fishes and the macro-invertebrate stable isotope data were generally between 2 and 4 ‰ (Fig. 2). For L. gibbosus, individuals of >106 mm all had δ15N fractionation factors with the macro-invertebrate data of >7 ‰ and between 3 and 4 ‰ with the other fishes (Fig. 2). There were significant relationships between TL and δ15N and δ13C in L. gibbosus; as fish length increased, δ15N increased and δ13C decreased (Fig. 3).

Stable isotope biplots per pond. NPS = no L. gibbosus; PS = L. gibbosus present. Clear circle gudgeon; clear triangle = R. rutilus; black triangle = T. tinca; black circle L. gibbosus. Clear square = mean macro-invertebrate stable isotope data (±SE), comprising of mean values of the triplicate samples of Chironomidae, Asellus aquaticus and Corixidae. Note differences in values of δ13C on the x-axes

Comparison of the stable isotope data for each native fish in the replicates of the two treatments suggested that there was a contraction in their isotopic space in L. gibbosus presence (Table 6; Fig. 2). For G. gobio, this was expressed as reduced δ13C ranges in L. gibbosus presence (mean 1.49 ± 0.44 vs. 2.04 ± 0.27 ‰), although their δ15N ranges were more similar (mean 1.89 ± 0.43 vs. 1.54 ± 0.39 ‰) (Table 6). A similar pattern was also apparent in the CV (Table 6). For R. rutilus, the CVs and ranges of both δ13C and δ15N were reduced in L. gibbosus presence (δ13C range: mean 0.57 ± 0.19 vs. 1.65 ± 0.71 ‰; δ15N range: mean 01.37 ± 0.37 vs. 1.92 ± 0.27 ‰) (Table 6). There were insufficient numbers of T. tinca and S. erythrophthalmus per replicate to warrant further analysis (Table 6). Comparisons of the 13C and 15N ranges of the fishes between the replicates and treatments are, however, of limited value due to considerable and significant differences in the isotopic values of the macro-invertebrate prey resources per replicate (ANOVA: δ13C F 5,12 = 21.25, P < 0.01; δ15N F 5,12 = 24.14, P < 0.01; Fig. 2). Thus, to enable comparison of the isotopic niches of the fish between the replicates required the stable isotope data to be converted to TP and Ccorr.

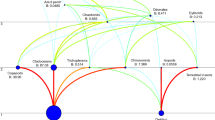

The linear mixed models comparing Ccorr and TP of G. gobio between the Control and Treatment ponds revealed significant differences in both parameters; there were significantly higher values of Ccorr in L. gibbosus presence (5.61 ± 1.46 vs. 2.40 ± 0.66; P < 0.01) but significantly lower TPs (2.56 ± 0.21 vs. 3.21 ± 0.09; P < 0.01). The same pattern was also evident for the TP of R. rutilus in L. gibbosus presence/absence (2.77 ± 0.21 vs. 3.44 ± 0.09; P < 0.01), but not for Ccorr (1.90 ± 1.62 vs. 0.72 ± 0.75; P = 0.36). These differences in the corrected isotopic values for these two native species between the two treatments were also reflected in their standard ellipse areas. Compared with pumpkinseed presence, SEAB was significantly smaller than in L. gibbosus presence for both G. gobio (0.59 vs. 1.92) and R. rutilus (0.28 vs. 1.94) (Fig. 4).

Biplots of isotopic niche (as SEAB) for: Top—Gobio gobio in Lepomis gibbosus presence (filled circle) and absence (clear circle); Middle—Rutilus rutilus in L. gibbosus presence (filled triangle) and absence (clear triangle); and Bottom—G. gobio (filled circle); R. rutilus (filled triangle) and L. gibbosus (clear square) in the pond with L. gibbosus present. Text in each plot provides the sample size and the 95 % confidence intervals of the SEAB estimates for each species and experimental treatment

Within the PS treatment, the linear mixed models revealed significant differences in Ccorr and TP between L. gibbosus and G. gobio (–0.63 ± 0.25 vs. 0.75 ± 0.31, P < 0.01; 3.35 ± 1.62 vs. 2.92 ± 0.20, P < 0.01, respectively). There were no significant differences between Ccorr and TP for L. gibbosus and R. rutilus (–0.63 ± 0.25 vs. 0.13 ± 0.50, P = 0.53; 3.35 ± 1.92 vs. 3.40 ± 0.22, P = 1.0, respectively). In the subsequent calculations of standard ellipse area, the data for the large (>106 mm) L. gibbosus were omitted, given that their TP and Ccorr values were markedly different to smaller conspecifics and the native fishes (Figs. 2, 3). The standard ellipse area of L. gibbosus <106 mm (1.21) was significantly larger than G. gobio (0.59) and R. rutilus (0.28), with an isotopic niche overlap of 48 and 30 % respectively (Fig. 4).

Discussion

In the present study, it was apparent that when comparing the isotopic niche sizes among experimental ponds where L. gibbosus were present and absent, both G. gobio and R. rutilus had significant reductions in their isotopic niche in L. gibbosus presence. Their isotopic niches also had high overlap with L. gibbosus, suggesting that the native and non-native fishes were sharing food resources. Although stomach contents data were not taken and the macro-invertebrate stable isotope data did not allow further discrimination between fish diets via mixing models due to low isotopic variability between invertebrate species, these constricted isotopic niches suggest some increased diet specialisation in the native fishes in L. gibbosus presence. This inference thus shows some consistency with the niche variation hypothesis, which predicts that under increased inter-specific competition, such as being incurred by a biological invasion, populations will become less generalised in their diet (Van Valen 1965; Thomson 2004; Olsson et al. 2009; Jackson et al. 2012). They also align strongly to the ecological consequences of invasive P. parva in studies of U.K. fish communities, which revealed strong patterns of niche constriction in native fishes in the presence of the invader (Jackson and Britton 2014; Tran et al. 2015).

Along with the identification of future, potentially invasive non-native species (e.g. Britton et al. 2010; Copp 2013), one of the most difficult tasks in the analysis of the potential risks they pose is the evaluation of impacts, whether ecological or socio-economic. This is particularly true for L. gibbosus, with the evidence for adverse ecological impacts in southern England being generally equivocal (Copp et al. 2010; Jackson et al. 2016). To the present, the detailed studies of L. gibbosus interactions with native fishes in England have reported the partition of available habitat (Vilizzi et al. 2012; Stakėnas et al. 2013) and food (Fobert et al. 2011). In the latter study, which examined the potential impact of L. gibbosus presence on the growth of native Eurasian perch Perca fluviatilis in the same experimental ponds as the present study, no effect on growth was observed in either species. To avoid competition, perch shifted its diet, which was predominantly Chironomidae, and consumed more micro-crustaceans, whereas L. gibbosus decreased its consumption of micro-crustaceans and increased its intake of Chironomidae. In the present study, a similar repartition of available prey was observed in the TPs and dietary breadth of the native fishes in the presence of L. gibbosus. However, this appeared to be achieved through diet specialisation rather than a shift in the dietary items consumed, with the native fishes constricting within their existing isotopic niche in L. gibbosus presence. Moreover, this resulted in a significant decline in G. gobio growth rate, which is best demonstrated in their shorter TL and lower K in the presence of L. gibbosus (Table 4); this suggests possible further ecological consequences, which remain untested and therefore at this time are speculative in nature.

The results of our study indicate that there was isotopic niche constriction in the native fishes that was driven by their trophic interactions with non-native L. gibbosus. This, however, comes with some caveats relating to study design. Firstly, they were calculated based on the assumption that the stable isotope fractionation factors between fin tissues and prey resources were identical across the fishes. However, studies including Tronquart et al. (2012) and Busst et al. (2015, 2016) suggest these can vary between species and different prey resources. Here, this assumption was used, as species-specific fractionation factors were not available for all the fishes. Secondly, due to the diets of the model fishes, and especially L. gibbosus, being dominated by macro-invertebrate species at the lengths being studied, the SIA focused on the interactions between these components of the pond communities. This meant, however, that the basis of the isotopic differences between NPS1 and all other ponds that were apparent in both the fish and macro-invertebrate data were unable to be explored further. This also meant that it was difficult to further explore the drivers of the very high TPs of the larger bodied L. gibbosus (>106 mm) compared to their smaller conspecifics. However, given that piscivory has been reported in larger, invasive L. gibbosus, partially via cannibalism (Guti et al. 1991; Copp et al. 2002, 2010), we speculatively suggest an ontogenetic shift to piscivory in these larger fish in the experimental ponds.

In addition to these caveats, these results were gained from small experimental ponds in which L. gibbosus were stocked in relatively high densities. This was deliberate in order to simulate the invasive conditions predicted for this species in the warmer climate forecasted for southern England (Britton et al. 2010). However, it also meant that the results could have been driven by density-dependence and thus might also have occurred had a native fish been used instead of L. gibbosus. Notwithstanding, the life-history traits of invaders such as L. gibbosus and P. parva generally facilitate their rapid establishment of highly abundant populations following an introduction (e.g. Copp and Fox 2007; Britton and Gozlan 2013). Thus, this scenario of a highly abundant invader within a pond community was ecologically realistic. Finally, an issue with many ecological experimental approaches is that patterns measured under controlled conditions in relatively short timeframes might not necessarily match those that would develop in larger systems over longer timeframes due to issues relating to the scaling up of experimental data to represent more complex natural situations (Korsu et al. 2009; Spivak et al. 2011; Vilizzi et al. 2015). However, small pond/mesocosm experiments have been used successfully to understand better the processes in force at larger ecological scales, with outputs of such studies often being highly consistent and relevant for understanding large-scale processes, but with the benefit of more controlled conditions and greater replication (Spivak et al. 2011). For example, the approach of Tran et al. (2015) on invasive P. parva revealed strong consistency in the ecological outcomes for native fishes between small-scale, experimental approaches and wild populations.

Thus, this experimental pond study provided empirical evidence for the potential ecological impacts of L. gibbosus for native pond fishes should the species become invasive as predicted (Britton et al. 2010). This is expected to manifest itself as reduced trophic niche sizes and growth rates, which is suggested by the differences in body mass and condition (plumpness) of G. gobio between the Control and Treatment ponds (Table 4). The reproduction of G. gobio in three of the experimental ponds (as well as the nearby angling ponds from where these specimens were sourced) indicates that the species is able to maintain self-sustaining populations in both still and running waters. However, G. gobio is most commonly associated with lotic rather than lentic habitats, so it is unfortunate that it was not amongst the native species included in the Jackson et al. (2016) study, using SIA, to explore potential impacts of pumpkinseed on the TP of native fishes in a neighbouring tributary stream catchment.

Although evidence for impacts by L. gibbosus in the U.K. have been limited to date, the most recent studies predict that L. gibbosus recruitment is likely to benefit from the forecasted warmer climate (Zięba et al. 2010; Fobert et al. 2013), resulting in higher densities (Zięba et al. 2015) and greater dispersal (Fobert et al. 2013). This is expected to increase interactions with native fishes, which in Iberia has been found to result in impacts to native species (Almeida et al. 2014). This has particular implications across Europe for freshwater ecosystems affected by human disturbance (e.g. Moyle 1986). For example, in southern Europe, river channelisation and the construction of reservoirs has resulted in fish assemblages being dominated by non-native fishes (e.g. Corbacho and Sánchez 2001; Morán-López et al. 2006; Ferreira et al. 2007; Almeida et al. 2009; Clavero et al. 2013). And in more northerly locations, such as the Netherlands, pond rehabilitation efforts to favour one taxonomic group (e.g. native aquatic plants) resulted in disturbance that favoured invasion of the ponds by L. gibbosus (Van Kleef et al. 2008). Thus, the outputs of the present study have wider implications beyond the U.K., indicating that the environmental consequences of L. gibbosus invasions are likely to include impacts on the TP and growth rates of some native fishes in European inland waters.

References

Almeida D, Almodóvar A, Nicola GG et al (2009) Feeding tactics and body condition of two introduced populations of pumpkinseed Lepomis gibbosus: taking advantages of human disturbances? Ecol Freshw Fish 18:15–23

Almeida D, Vilizzi L, Copp GH (2014) Interspecific aggressive behaviour of invasive pumpkinseed Lepomis gibbosus in Iberian fresh waters. PLoS One 9:e88038

Angeler DG, Álvarez-Cobelas M, Sánchez-Carrillo S et al (2002a) Assessment of exotic fish impacts on water quality and zooplankton in a degraded semi-arid floodplain wetland. Aquat Sci 64:76–86

Angeler DG, Rodrigo MA, Sánchez-Carrillo S et al (2002b) Effects of hydrologically confined fishes on bacterioplankton and autotrophic picoplankton in a semiarid marsh. Aquat Microbiol Ecol 29:307–312

Britton JR, Gozlan RE (2013) How many founders for a biological invasion? predicting introduction outcomes from propagule pressure. Ecology 94:2558–2566

Britton JR, Shepherd JS (2005) Biometric data to facilitate the diet reconstruction of piscivorous fauna. Folia Zool 54:193–200

Britton JR, Cucherousset J, Davies GD et al (2010) Non-native fishes and climate change: predicting species responses to warming temperatures in a temperate region. Freshw Biol 55:1130–1141

Busst G, Britton JR (2016) High variability in stable isotope diet–tissue discrimination factors of two omnivorous freshwater fishes in controlled ex situ conditions. J Exp Biol 219:1060–1068

Busst G, Bašić T, Britton JR (2015) Stable isotope signatures and trophic-step fractionation factors of fish tissues collected as non-lethal surrogates of dorsal muscle. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 29:1535–1544

Clavero M, Hermoso V, Aparicio E et al (2013) Biodiversity in heavily modified waterbodies: native and introduced fish in Iberian reservoirs. Freshw Biol 58:1190–1201

Copp GH (2008) Putting multi-dimensionality back into niche breadth: diel vs. day-only niche separation in stream fishes. Fund Appl Limnol 170:273–280

Copp GH (2013) The Fish Invasiveness Screening Kit (FISK) for non-native freshwater fishes: a summary of current applications. Risk Anal 33:1394–1396

Copp GH, Fox MG (2007) Growth and life history traits of introduced pumpkinseed (Lepomis gibbosus) in Europe, and the relevance to invasiveness potential. In: Gherardi F (ed) Freshwater bioinvaders: profiles, distribution, and threats. Springer, Berlin, pp 289–306

Copp GH, Fox MG, Kováč V (2002) Growth, morphology and life history traits of a coolwater European population of pumpkinseed Lepomis gibbosus. Arch Hydrobiol 155:585–614

Copp GH, Vilizzi L, Mumford JD, Fenwick GV, Godard MJ, Gozlan RE (2009) Calibration of FISK, an invasive-ness screening tool for non-native freshwater fishes. Risk Analy 29:457–467

Copp GH, Stakėnas S, Cucherousset J (2010) Aliens versus the natives: interactions between introduced pumpkinseed and indigenous brown trout in small streams of Southern England. Am Fish Soc Symp 73:347–370

Copp GH, Russell IC, Peeler EJ et al (2014) European non-native species in aquaculture risk analysis scheme: a summary of assessment protocols and decision making tools for use of alien species in aquaculture. Fish Manag Ecol. doi:10.1111/fme.12074

Corbacho C, Sánchez JM (2001) Patterns of species richness and introduced species in native freshwater fish faunas of a Mediterranean-type basin: the Guadiana River (southwest Iberian Peninsula). Regul Rivers Res Manag 17:699–707

Cornell University Stable Isotope laboratory (2015) Preparation guidelines. http://www.cobsil.com/iso_main_preparation_guidlines.php. Last Accessed 22 May 2015

Cucherousset J, Bouletreau S, Martino A et al (2012) Using stable isotope analyses to determine the ecological effects of non-native fishes. Fish Manag Ecol 19:111–119

Domínguez J, Pena JC, De Soto J, Luis E (2002) Alimentación de dos poblaciones de perca sol (Lepomis gibbosus), introducidas en el Norte de España: Resultados perliminares. Limnética 21:135–144

Dossena M, Yvon-Durocher G, Grey J et al (2012) Warming alters community size structure and ecosystem functioning. Proc R Soc Lond B 279:3011–3019

Ferreira MT, Oliveira J, Caiola N et al (2007) Ecological traits of fish assemblages from Mediterranean Europe and their responses to human disturbance. Fish Manag Ecol 14:473–481

Fobert E, Fox MG, Ridgway M et al (2011) Heated competition: how climate change will affect competing non-native pumpkinseed and Eurasian perch in the U.K. J Fish Biol 79:1592–1607

Fobert E, Zięba G, Vilizzi L et al (2013) Predicting non-native fish dispersal under conditions of climate change: case study in England of dispersal and establishment of pumpkinseed Lepomis gibbosus in a floodplain pond. Ecol Freshw Fish 22:106–116

García-Berthou E, Moreno-Amich R (2000) Food of introduced pumpkinseed sunfish: ontogenetic diet shift and seasonal variation. J Fish Biol 57:29–40

Godinho FN, Ferreira MT, Cortes RV (1997) The environmental basis of diet variation in pumpkinseed sunfish, Lepomis gibbosus, and largemouth bass, Micropterus salmoides, along an Iberian river basin. Environ Biol Fish 50:105–115

Gozlan RE (2008) Introduction of non-native freshwater fish: is it all bad? Fish Fish 9:106–115

Gozlan RE, Britton JR, Cowx IG et al (2010) Current knowledge on non-native freshwater fish introductions. J Fish Biol 76:751–786

Guti G, Andrikowics S, Bíró P (1991) Food of pike (Esox lucius), mud minnow (Umbra krameri), crucian carp (Carassius carassius), catfish (Ictalurus nebulosus), pumpkinseed (Lepomis gibbosus) at Ócsa bog, Hungary. (In German, with English title, abstract, figure and table legends). Fischökologie 4:45–66

Hobson KA, Clark RG (1992) Assessing avian diets using stable isotopes I: turnover of 13C in tissues. Condor 94:181–188

Jackson MC, Britton JR (2014) Does sympatry result in niche convergence or divergence in freshwater invasive species? Biol Invasions 16:1095–1103

Jackson AL, Inger R, Parnell AC et al (2011) Comparing isotopic niche widths among and within communities: Bayesian analysis of stable isotope data. J Anim Ecol 80:595–602

Jackson MC, Jackson AL, Britton JR et al (2012) Population level metrics of trophic structure based on stable isotopes and their application using invasion ecology. PLoS One 7:e31757

Jackson MC, Britton JR, Cucherousset J et al (2016) Do non-native pumpkinseed Lepomis gibbosus affect the growth, diet and trophic niche breadth of native brown trout Salmo trutta? Hydrobiologia 772:63–75

Kakareko T, Kobak J, Grabowska J et al (2013) Competitive interactions for food resources between invasive racer goby Babka gymnotrachelus and native European bullhead Cottus gobio. Biol Invasions 15:2519–2530

Kennedy M, Fitzmaurice P (1972) Some aspects of the biology of gudgeon Gobio gobio (L.) in Irish waters. J Fish Biol 4:425–440

Korsu K, Huusko A, Muotka T (2009) Does the introduced brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) affect growth of the native brown trout (Salmo trutta)? Naturwissenschaften 96:347–353

Morán-López R, da Siva E, Perez-Bote JL et al (2006) Associations between fish assemblages and environmental factors for Mediterranean-type rivers during summer. J Fish Biol 69:1552–1569

Moyle PB (1986) Fish introductions into North America: patterns and ecological impact. In: Drake JA, Mooney HA (eds) Ecology of biological invasions of North America and Hawaii: ecological studies, vol 58. Springer, New York, pp 27–43

Nikolova M, Uzunova E, Studenkov S et al (2008) Feeding patterns and seasonal variation in the diet of non-indigenous fish species Lepomis gibbosus L. from shallow eutrophic lakes along River Vit, Bulgaria. Nat Monten 7(3):71–85

Olsson K, Stenroth P, Nyström P et al (2009) Invasions and niche width: does niche width of an introduced crayfish differ from a native crayfish? Freshw Biol 54:1731–1740

Persson L, Greenberg LA (1990) Juvenile competitive bottlenecks: the perch (Perca fluviatilis)-roach (Rutilus rutilus) interaction. Ecology 7:44–56

Post DM (2002) Using stable isotopes to estimate trophic position: models, methods, and assumptions. Ecology 83:703–718

Post DM, Layman CA, Arrington DA, Takimoto G, Quattrochi J, Montana CG (2007) Getting to the fat of the matter: models, methods and assumptions for dealing with lipids in stable isotope analyses. Oecologia 152:179–189

R Development Core Team (2014) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org

Rezsu E, Specziár A (2006) Ontogenetic diet profiles and size-dependent diet partitioning of ruffe Gymnocephalus cernuus, perch Perca fluviatilis and pumpkinseed Lepomis gibbosus in Lake Balaton. Ecol Freshw Fish 15:339–349

Santos RE, Silva TP, Chehayeb IV et al (2012) Reproduction of the non-native fish Lepomis gibbosus (Perciformes: Centrarchidae) in Brazil. Rev Biol Trop 60:1327–1334

Shea K, Chesson P (2002) Community ecology theory as a framework for biological invasions. Trends Ecol Evol 17:170–176

Spivak AC, Vanni MJ, Mette EM (2011) Moving on up: can results from simple aquatic mesocosm experiments be applied across broad spatial scales? Freshw Biol 56:279–291

Stakėnas S, Vilizzi L, Copp GH (2013) Habitat use, home range, movements and interactions of introduced Lepomis gibbosus and native Salmo trutta in a small stream of Southern England. Ecol Freshw Fish 22:202–215

Svanbäck R, Bolnick DI (2007) Intraspecific competition drives increased resource use diversity within a natural population. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 274:839–844

Thomas SM, Crowther TW (2015) Predicting rates of isotopic turnover across the animal kingdom: a synthesis of existing data. J Anim Ecol 84:861–870

Thomson D (2004) Competitive interactions between the invasive European honey bee and native bumble bees. Ecology 85:458–470

Tran TNQ, Jackson MC, Sheath D et al (2015) Patterns of trophic niche divergence between invasive and native fishes in wild communities are predictable from mesocosm studies. J Anim Ecol 84:1071–1080

Tronquart NH, Mazeas L, Reuilly-Manenti L, Zahm A, Belliard J (2012) Fish fins as non-lethal surrogates for muscle tissues in freshwater food web studies using stable isotopes. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 26:1603–1608

Van Kleef HH, Van der Velde G, Leuven RSE et al (2008) Pumpkinseed sunfish (Lepomis gibbosus) invasions facilitated by introductions and nature management strongly reduce macroinvertebrate abundance in isolated water bodies. Biol Invasions 10:1481–1490

Van Valen L (1965) Morphological variation and width of ecological niche. Am Nat 99:377–390

Vilizzi L, Stakėnas S, Copp GH (2012) Use of constrained additive and quadratic ordination in fish habitat studies: an application to introduced pumpkinseed (Lepomis gibbosus) and native brown trout (Salmo trutta) in an English stream. Fund Appl Limnol 180:69–75

Vilizzi L, Tarkan AS, Copp GH (2015) Experimental evidence from causal criteria analysis for the effects of common carp Cyprinus carpio on freshwater ecosystems: a global perspective. Rev Fish Fish 23:253–290

Williams P, Whitfield M, Biggs J et al (2003) Comparative biodiversity of rivers, streams, ditches and ponds in an agricultural landscape in Southern England. Conserv Biol 115:329–341

Woodford DJ, Impson ND, Day JA et al (2005) The predatory impact of invasive alien smallmouth bass, Micropterus dolomieu (Teleostei: Centrarchidae), on indigenous fishes in a Cape Floristic Region mountain stream. Afr J Aquat Sci 30:167–173

Zięba G, Fox MG, Copp GH (2010) The effect of elevated temperature on spawning frequency and spawning behaviour of introduced pumpkinseed Lepomis gibbosus in Europe. J Fish Biol 77:1850–1855

Zięba G, Fox MG, Copp GH (2015) How will climate change affect non-native pumpkinseed Lepomis gibbosus in the U.K.? PLoS One 10:e0135482

Acknowledgments

As a direct derivative of the network ‘Life-history traits as predictors in assessing risks of non-native fishes’, which was initially funded by a NATO Collaborative Linkage Grant awarded to GHC, the present study was funded by the U.K. Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, with subsequent complementary support from Cefas Seedcorn contract DP372. We thank Bedwell Fish Farms for supplying tench for the study and the landowners for the construction of the ponds and their permission to carry out our investigations in the private part of their property.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Copp, G.H., Britton, J.R., Guo, Z. et al. Trophic consequences of non-native pumpkinseed Lepomis gibbosus for native pond fishes. Biol Invasions 19, 25–41 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-016-1261-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-016-1261-8