Abstract

Legislation on biological invasions has been evolving in recent decades. The use of lists of harmful alien organisms (LHAO) is becoming a widespread policy practice in many countries. LHAO aims to prevent the introduction of undesirable organisms at the pre-border level, regulate their use within the country and deter their spread. However, a systematic review and comparison of the current legislations is lacking. It remains unknown whether there are gaps or weaknesses that may compromise and effective strategy against biological invasions. In this study, a total of 77 LHAO from Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Spain, South Africa, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States of America were evaluated and compared in terms of the taxonomic criteria of inclusion, the impacts of concern and the activities regulated. The number of LHAO has increased exponentially since 1924. Countries widely varied in the number of lists. Within a country, LHAO are scattered across different regulations that consider different impacts and regulate activities from introduction to management. The number of taxa ranged between 0.15 and 55.4 taxa km−2 in the USA and New Zealand, respectively. These lists totaled 21,029 records of 18,149 different taxa, showing a prevalence of taxa listed as species (rather than genera of higher ranks). Primary attention is paid to the kingdoms Animalia and Plantae. Taxa affecting livelihood/uses were more prevalent than those related to biodiversity and human health impacts. The most common regulations concern trade and tenure followed by use. This study reveals the need for more comprehensive (intersectoral) regulations on invasive alien species within countries as well as the development of homogeneous regulations adapted to the globalized world.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biological invasions are a growing problem throughout the world in the context of globalization. Direct and indirect impacts of invasive species on native ecosystems, productive systems and human health (Pimentel et al. 2005; Colautti et al. 2006; Hulme et al. 2009) require the development of management measures aimed at slowing the introduction of new invasive species and correcting the negative effects of already established invasions. The development of legislation is a cornerstone to prevent future invasions. Progress has been made with legislation related to harmful alien organisms over the last decades, however, problems related to biological invasions continue to grow worldwide (McGeoch et al. 2010; Essl et al. 2011a; Pyšek et al. 2011; Crooks 2011). It is therefore imperative to review the current legislation to detect specific weaknesses that compromise an effective strategy against biological invasions.

A number of international agreements and conventions have recognized the problems related to the global trade of living organisms (Table 1). The World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), founded in 1924, and the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) founded in 1951, aim to ensure the sanitary safety of the international trade of animals and plants and their products, respectively. The OIE and the IPPC have historically focused on pests that affect commercial species but whose effects can spread to wild species or may even affect humans (zoonosis) (FAO 1997; OIE 2013a, b). The international standards, guidelines and recommendations developed by the OIE and the IPPC are the basis for development and application of sanitary and phytosanitary measures at a national scale which may, directly or indirectly, affect international trade. Such measures will be consistent with the provisions of the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary measures (SPS). More recent conventions such as the Wetlands Convention in 1971 and the Rio de Janeiro Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 1992 have marked a turning point in the concern for environmental issues in general, including biological invasions as a threat to biodiversity (Table 1). However, these conventions are not binding or have not yet entered into force internationally (e.g., Ballast Water Convention). Moreover, mechanisms responsible for the majority of the introduction of alien species on a global scale (e.g., importation of commodities, arrival of a transport vector, natural spread from a neighboring region) remain unregulated (Hulme et al. 2008; Hulme 2009). Specific global measures have been taken to regulate certain dangerous organisms, for example, in response to new outbreaks of emerging diseases. This has been the case of the red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta elegans) responsible for salmonellosis (Woodward et al. 1997); prairie dogs (Cynomis sp.) and Gambian giant rats (Cricetomys gambianus) responsible for monkey-pox (Reed et al. 2004); poultry and pet birds responsible for avian flu (Peiris et al. 2007); and civets (family viverridae) responsible for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (Guan et al. 2003).

The use of national lists including alien species with known invasive potential (commonly referred to as blacklists or dirty lists) is becoming a growing practice in different countries. Lists of harmful alien organisms (hereinafter LHAO) prevent the introduction of new harmful alien species in a certain territory (preventive or warning approach) or regulate the use of well-known invaders that are already present in the territory (reactive approach) (Burgiel et al. 2006). LHAO also cover the legal need to identify invasive alien species to which the regulation applies. LHAO may be useful for preventing the introduction of undesirable organisms at the pre-border level. For example, potential exporters can check these lists to see if the import of the species in question is permitted, or if special authorizations or certificates are required. These lists provide greater transparency and predictability for exporters before the products are collected, packaged and shipped. Also, the LHAO helps border and quarantine inspectors to control incoming goods. However, the effectiveness of this approach has been questioned by several authors (e.g., Simberloff 2001, 2006; Padilla and Williams 2004; Fowler et al. 2007; Brasier 2008). First, all unlisted organisms may remain unregulated, leaving the door open to the trade of alien species of unknown risk (Simberloff 2006; Fowler et al. 2007; Jenkins et al. 2007; Brasier 2008). Second, including one new harmful species on the list is too slow (except in the case of new outbreaks of potentially fatal pandemics), thereby limiting fast response actions to new threats (Brasier 2008). Third, national LHAO poorly cover the possible mismatch between political boundaries for which current lists are applied and the natural distribution of species. Therefore, species (either native or alien) that exist within a territory can become invasive when introduced elsewhere in the country, the continent and other land masses with shared with multiple countries (Simberloff 2006). Fourth, varying legislation among neighboring countries may create openings for invasive species. These criticisms inspired the present revision of blacklists.

In this paper, we analyze LHAO that are legally binding (regulated) and in force in eight countries from five continents. We aim to evaluate to what extent they share design criteria and contents. Specifically, the following questions were addressed: (1) How many taxa are listed with respect to country size? (2) What taxonomic ranks and kingdoms are included? (3) What impacts are considered? (4) and What activities are regulated?

Materials and methods

Selection of LHAO

The assessment focused on LHAO including pests, pathogens (e.g., plant pest lists, disease and infection agents in the OIE and the IPPC), invasive species (e.g., blacklists or dirty lists) or their vectors. LHAO from eight countries on five continents were selected encompassing a broad scope of geographic and socioeconomic characteristics: Australia, Japan, New Zealand, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the USA. All of these countries are members of OIE and IPPC and have developed specific legislation on biological invaders. Government webpages and official webpages of the OIE (http://www.oie.int/en/) and the IPPC (https://www.ippc.int/countries/regulatedpests/, last accession 22 December 2013) were consulted. The LHAO that are in force and are supported by national legislative frameworks were selected, not restricted to a specific period. Considering that the legislation is continuously updated, the search did not include updates after December 2013. Overall, the following datasets were not included: (1) lists of alien organisms that are not legally binding; (2) national pest lists including taxa not identified as alien; (3) state or regional lists below the country level; (4) programs or acts specifically focused on the management of certain species but not regulating their introduction into the country or their use within the country (e.g. the Asian carp dispersal barrier project within the Water Resource Development Act in the USA); (5) species regulated in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, CITES). In total, 77 blacklists were selected (see Supp. Mat.).

Description of LHAO contents: number of organsims, taxonomy, impacts and activities regulated

For each blacklist, the year of entry into force and the number of taxa regulated in each country was recorded; the density of records with respect to the size of the country was also calculated. Taxa repetitions among blacklists within a country were removed (for example, Heracleum mantegazzianum is listed in the US Federal Noxious Weed list, the Regulated Plant Pest List and in title 7 of CFR (2013). First, the number of taxa regulated in each country was counted. The contribution of each taxonomic rank was calculated, taking into consideration 4 categories: “subspecies, varieties, hybrids or strains”, “species”, “genera” and “families or higher rank”. Each taxon listed was also assigned to a kingdom. For simplicity, the five-kingdom system proposed by Whittaker (1969) was used, as well as an additional group incorporating viruses, viroids and prions.

Impact information of the listed species was obtained from electronic databases such as the Global Invasive Species Database (http://www.issg.org/database/species), the Invasive Species Compendium (http://www.cabi.org/isc/) and others compiled by Simons and De Poorter (2009) and the Secretariat of the CBD (2010). For the New Zealand LHAO (over 14,800 records), the Unwanted Organisms database (http://www1.maf.govt.nz/uor/.htm) was also used. When no information was available in these databases, further information was searched in papers published on the ISI Web of Science. Impacts were summarized into three categories: (1) biodiversity (negative consequences on native species or ecosystems), (2) human health such as problems derived from disease transmission, poisoning or allergies, and (3) livelihood and uses, including losses in agriculture, livestock, forestry production and fisheries as well as impacts on infrastructures.

Among the activities regulated, the sixteen categories initially recorded were combined into 6 categories including “introduction” (or release into the wild), “trade” (import, export, acquisition, buy or sell), “use” (raise, propagate, multiply, field test, research or use in the environment), “tenure” (posses, hold in captivity, store, transport, carry, move, translocate, exhibit, receive, give, donate or accept as a gift), “quarantine” (pre- or post-quarantine, inspection, certification and notification), and “elimination” (control, combat and eradication). Other variables such as the resources invested in ensuring compliance with the regulation (e.g., number and skills of inspectors, number of geographical points monitored, techniques used for detection, proportion of goods inspected, etc.) were not systematically included in this study because of the dispersion and opacity of the information.

Statistical analysis

Countries were classified according to the listed organisms characteristics in taxonomic ranks, kingdoms and impacts and activities regulated by using a hierarchical cluster analysis (Clarke and Warwick 2001). Prior to clustering, all variables were standardized to balance their weight on total variance. The group average and Bray-Curtis distance were chosen as cluster algorithm and similarity measures, respectively. A similarity profile test (SIMPROF) was performed on a null hypothesis that a specific subcluster can be recreated by permuting the entry of countries and variables. The significant branch (SIMPROF, p < 0.05) was used as a prerequisite for defining the country groups. Analyses were performed using the statistical software Primer-E version 6.1.6 (Clarke and Warwick 2001).

Results

Our database includes a total of 77 LHAO with 21,029 records of 18,149 different taxa (see Suppl. Mat.). Taking into account the year in which each list came into force, the number of lists have shown an exponential increase over time since the first one was published in 1924 (Fig. 1). This date corresponds to the entry into force of the Office International des Epizooties (World Organization for Animal Health) which was first signed by 28 countries including the UK, Spain and Switzerland (all the countries analyzed are currently OIE members). In the last 25 years there has been a clear rise in regulatory efforts, encompassing 73 % of the implemented LHAO. Over 90 % of taxa are unique and regulated in a single country, 1533 taxa (8.4 %) are regulated in more than one country and only 98 taxa (0.5 %) are common to all countries (Fig. 2). These “common hazards” are included in the OIE-listed diseases, infections and infestations now in force, as all the countries analyzed are members of the World Organization for Animal Health.

Number of national lists of harmful alien organisms emerged over time in Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Spain, South Africa, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the USA. For each list, the year of entry into force was considered. The solid line represents the exponential adjustment of the accumulated number of lists (y) with time (x): y = 9 × 10−44 × e0.0514x; R2 = 0.98, n = 77

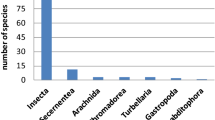

The density and composition of LHAO showed evident contrasts among countries. New Zealand regulated the highest number of taxa (14,831), followed by Japan (1334), USA (1331) and Australia (1274) (Table 2). The lowest number of taxa were listed in Switzerland (371), followed by the UK (456) and Spain (546). These values give only a rough idea of the real extent of LHAO, since different taxonomic ranks are often included. For example, the Tephritidae (Diptera) listed for European countries includes at least 23 alien species of 7 different genera (Council Directive 2000/29/EC). Regarding taxonomic ranks, the UK, Spain, New Zealand, South Africa and Switzerland exhibited the highest proportion of taxa listed as species (≥79 %), whereas the contribution of genera and higher ranks exceeded 20 % of the records in Australia, Japan and USA (Table 2).

Major attention is paid to the kingdoms Animalia and Plantae. However, the contribution of the different kingdoms widely varied among countries (Table 2). The Fungi kingdom was underrepresented in South Africa (only 3 records) while it included more than 4200 taxa in New Zealand. The Protista kingdom accounted for 13–19 records (Table 2), where most of them were common to all countries and were supported by the OIE (e.g., Babesia ovis, Bonamia exitiosa or Trypanosoma brucei).

Regarding impacts, taxa affecting the livelihood/uses, including agricultural plagues and livestock diseases, were dominant over biodiversity and human health impacts. Taxa affecting human health represented a minor proportion of the taxa listed (Table 2). New Zealand blacklists paid the most attention to taxa affecting livelihood/uses (i.e., agricultural plagues). Only Australia included more taxa affecting biodiversity than other impacts.

Different LHAO imposed different restrictions. Trade, tenure and use are the most frequently regulated activities (Table 3). In contrast, introduction or release into the wild, and elimination are scarcely regulated. Surprisingly, within trade, exportation was only exceptionally regulated by the Spanish Catalogue of Invasive Alien Species (Royal Decree 630/2013) and for some weeds listed in the USA included on the Federal Noxious Weed List (Executive Order 13112, 1999). Introduction and elimination was only considered for a small proportion of taxa regulated.

The cluster analysis revealed that the countries analyzed can be classified in three significant groups (Fig. 3, p < 0.05) regarding their similarities in taxonomy, the impact of the listed taxa and the activities regulated. The greatest similarities were found between Spain and Switzerland, Japan and the USA, and Australia and South Africa. All these countries shared a similarity of ca. 0.85, while New Zealand and the UK were not significantly similar to any other countries.

Dendrogram for 77 lists of harmful alien organisms from eight countries, using Bray-Curtis paired-group clustering similarities. The variables used were the number of listed taxa, and the contribution of each taxonomic rank (4 categories: “subspecies”, “species”, “genera” and “families or higher”), kingdoms (6 categories: “viruses, prions and viroids”, “bacteria”, “protista”, “fungi”, “plantae” and “animalia”), the impact type of the organism (3 categories: “biodiversity”, “human health”, “livelihood and uses”), and the activity regulated (6 categories: “introduction”, “trade”, “use”, “tenure”, “quarantine” and “elimination”). Dotted branches indicate significant groups where the similarity profile (SIMPROF) test suggests that the structure is not random (p < 0.05)

Discussion

Public awareness, management and policy are key actions in slowing problems derived from biological invasions. However, despite the progress of legislation regulating the trade of living organisms, biological invasions continue to grow worldwide. LHAO help to prevent the introduction of undesirable organisms at the pre-border level and reduce the spread of harmful organisms within a territory (intra-border). The exponential increase in the number of national LHAO in the last few decades highlights the growing interest in regulating harmful alien organisms. Fortunately, several countries not analyzed in this study (with regulation proposals still not in force as of December 2013) are developing LHAO, such as Norway (Gederaas et al. 2012), Germany (Essl et al. 2011b), Belgium (Invasive Species in Belgium, http://ias.biodiversity.be/), Argentina (http://www.inbiar.org.ar/), Costa Rica (Chacón and Saborío 2012) and Mexico (Comité Asesor Nacional sobre Especies Invasoras 2010).

The analysis of national LHAO revealed some similarities but also particular differences. Among the similarities, most countries pay special attention to the kingdoms Animalia and Plantae. The contribution of these kingdoms is even lower than expected regarding their contribution to total biodiversity (75 and 16 %, respectively; IUCN 2012). Most taxa are listed as species that affect livelihood followed by biodiversity. These criteria could be related in terms of many variables not analyzed in this study such as taxonomic biases in invasion knowledge (Pyšek et al. 2008) or unequal awareness of ecological and economic impacts (Miller 2005; Richardson and Pyšek 2008; Vilà et al. 2011; Jeschke et al. 2014). The minor contribution of taxa affecting human health seems rather low despite its impact on social perception. Cluster analysis revealed significant similarities among 6 of the 8 countries analyzed in terms of taxonomic rank, kingdom, impact and activities regulated. However, standardization of variables prior to clustering smoothes some big differences in variables such as the number and density of taxa regulated. Surprisingly, Spain and the UK shared few similarities and were grouped in different clusters despite both countries belonging to the European Union. These differences are mainly due to the activities regulated. In fact, there are a small proportion of taxa for which introduction is prohibited or elimination is regulated, suggesting the need for criteria to develop more homogenous legislations.

The number of national LHAO applicable to each country as well as the contribution of certain kingdoms and impacts, was highly variable among countries. The number of LHAO ranged from 2 (South Africa) to over 42 (USA) (see Suppl. Mat.), whereas the density of taxa ranged between 0.15 and 55.40 taxa km−2 in the USA and New Zealand, respectively. A greater number of regulated organisms will increase biosecurity levels but involve greater complexity for compliance. Similarly, the inclusion of genera or higher ranks potentially prevents the introduction of sister species but increases the real number of taxa listed. Longer lists may require greater efforts for compliance and the training of inspectors to be able to recognize all listed species, genera and families of different kingdoms. Finding out how effectively each country regulates harmful alien organisms was not the aim of this work. Resources invested in inspection tasks (e.g., number of inspection points, proportion of goods revised at each inspection point) are essential for compliance with national regulations (Perrings et al. 2005; Keller et al. 2007).

There are three non-exclusive reasons for the variability of LHAO. First, the regulation of alien species is often promoted by different Departments or Ministries. For example, US acts and federal regulations come from three different Departments (Agriculture, Interior, and Health and Human Services) and several Services within each Department (APHIS, ARS, USFS, FWS, CDC) (Miller 2011). As a consequence, over 50 % of lists analyzed regulate taxa which mostly affect only a single sector (impact category). No general comprehensive regulation (i.e., intersectoral law including alien taxa affecting biodiversity, livelihood and human health) on invasive alien species is available for any of the countries analyzed. Even the New Zealand Biosecurity Act, which has been regarded as one of the most comprehensive approaches to prevent biological invasions, is biased towards agriculture, horticulture and forestry (Takahashi 2006). This sectorization found at the national scale calls for greater coordination among agencies responsible for biodiversity conservation, agronomy and human health to provide more integrative regulations (Wade 1995; Hulme et al. 2010). Framing biological invasions by considering their impact on ecosystem services might contribute to this integration (Vilà et al. 2010). Second, despite that international risk assessment protocols for the importation of live alien species are available (Simons and De Poorter 2009; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity 2010; FAO 2011, 2013) each country has developed its own protocols. Risk assessment protocols are heterogeneous concerning their components, impact categories considered, data requirements, scoring methods, uncertainty evaluation, etc., which may result in inconsistencies of risk assessment outcomes when screening similar species (Verbrugge et al. 2010; Leung et al. 2012). Third, there is no international guidelines defining how many and what type of taxa should be listed regarding, for example, the geographical features of the country (size, population, magnitude of trade, diversity of habitats), or the magnitude of the biological invasion problem already present in the country or in neighboring countries. Should a given proportion of taxa that are already naturalized in the country be included? Should all invasive taxa already present in the country be included? Should taxa having impacts in various sectors (e.g. conservation of biodiversity/human health/livelihood) be prioritized? The lack of international guidelines homogeneously applied in countries from different continents, or even within the same continent, creates weaknesses or gaps in blacklisting, thereby creating openings for the introduction of new invaders.

In compliance with the global nature of the spread and impacts of biological invasions, the European Union developed an innovative environmental legislation on invasive species (Regulation 1143/2014), which has been in force since 1st January 2015. This Regulation aims to establish a common, homogenous response to threats to biodiversity and ecosystem services posed by biological invasions that is applicable to all Member States, therefore nearly at a continental scale. The initial draft of this Regulation proposed a list with a cap of only 50 taxa. This short list received considerable criticism (Carboneras et al. 2013) and was later rejected. The EU Regulation foresees the creation in early 2016 of a list of “Invasive Alien Species of Union concern”. Taxa included on this list will be selected based on risk analysis of their invasion potential, ecological impacts and spread in the face of climatic change (Genovesi et al. 2015). Coordination between Member states that share invasive species is encouraged, as well as the development of further measures that include invasive alien species at a national scale which may be native in other parts of the EU. The EU Regulation includes a ban on the import, trade, possession, breeding, transport, use and release into the environment of the listed species. Unlike other national regulations analyzed in this paper, no quarantine actions are considered.

A clear observation of our analysis is that taxa are widely dispersed under different regulations and each one regulates different activities. Despite the fact that up to sixteen categories of organism use are regulated, certain introduction pathways of alien organisms worldwide (e.g., the Internet) remain scarcely regulated or the existing regulations have not yet entered into force internationally (e.g., Ballast Water Convention) (Lodge et al. 2006; Derraik and Philips 2010). Given that the countries analyzed belong to different biogeographic regions, it seems logical that the similarity in the composition of regulated taxa among countries was low (over 90 % of taxa listed were unique). However, the fact that 98 taxa were common to all the countries confirms that some harmful alien organisms may represent a global threat indicating the need of global, harmonized regulations.

Overall, our analysis shows that the selected countries regulate a high variety of organisms (from prions to mammals) that affect biodiversity, livelihood and human health. Most of the regulations analyzed (80 %) have been developed over the last three decades, which reveals the growing interest in biological invasions and the legislative efforts made to control them. Nearly all countries selected for this study are among the top 30 countries in the world in Gross Domestic Product (IMF 2013). The positive relationship between economic development and trading and biological invasions (Vilà and Pujadas 2001) calls for international efforts to standardize legislation on harmful alien species. Furthermore, national regulations could be supplemented with “white” lists, consisting of species with no risk of invasion (Boudouresque and Verlaque 2002), and even with “grey” (watch) lists, containing potential risk species (Genovesi and Shine 2011). Otherwise, unlisted taxa will be imported as an alternative to listed species, thus increasing the risk of introduction of novel invaders. This multiple listing approach is currently in place in Australia (see list of permitted seeds in Schedule 5 of Quarantine Proclamation of 1998). The obligation to conduct a risk analysis for any taxa not blacklisted before its introduction, as proposed by Spanish Catalogue of Invasive Alien Species, is a preventive approach that may help to reduce the negative effects of alien species.

References

Boudouresque CF, Verlaque M (2002) Biological pollution in the Mediterranean Sea: invasive versus introduced macrophytes. Marine Pollut Bull 44:32–38

Brasier CM (2008) The biosecurity threat to the UK and global environment from international trade in plants. Plant Pathol 57:792–808

Burgiel S, Foote G, Orellana M, Perrault A (2006) Invasive alien species and trade: integrating prevention measures and international trade rules. Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) and Defenders of Wildlife (http://www.cleantrade.net). Accessed 2 May 2013

Carboneras C, Watson P, Vilà M (2013) Capping progress on invasive species? Science 342:930–931

CFR (2013) Code of federal regulations. U.S. Government Printing Office. U.S. Superintendent of Documents, Washington, DC. Available in http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/browse/collectionCfr.action?collectionCode=CFR. Last Accessed 30 Dec 2013

Chacón E, Saborío G (2012) Red Interamericana de Información de Especies Invasoras, Costa Rica. Asociación para la Conservación y el Estudio de la Biodiversidad, San José, Costa Rica. http://invasoras.acebio.org. Accessed 20 July 2013

Clarke KR, Warwick RM (2001) Change in marine communities: an approach to statistical analysis and interpretation. PRIMER-E, Plymouth

Colautti RI, Bailey SA, van Overdijk CDA, Amundsen K, MacIsaac HJ (2006) Characterised and projected costs of nonindigenous species in Canada. Biol Invasions 8:45–59

Comité Asesor Nacional sobre Especies Invasoras (2010) Estrategia nacional sobre especies invasoras en México, prevención, control y erradicación. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, Comisión Nacional de Áreas Protegidas, Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. México

Crooks JA (2011) Lag times. In: Simberloff D, Rejmánek M (eds) Encyclopedia of biological invasions. University of California Press, Berkeley, pp 404–410

Derraik JGB, Philips S (2010) Online trade poses a threat to biosecurity in New Zealand. Biol Invasions 12:1477–1480

Essl F, Lambdon P, Rabitsch W (2011a) Bryophytes and lichens. In: Simberloff D, Rejmánek M (eds) Encyclopedia of biological invasions. University of California Press, Berkeley, pp 81–85

Essl F, Nehring S, Klingenstein F, Milasowszky N, Nowack C, Rabitsch W (2011b) Review of risk assessment systems of IAS in Europe and introducing the German-Austrian Black List Information System (GABLIS). J Nat Conserv 19:339–350

FAO (1997) International plant protection convention (new revised text approved by the FAO conference at its 29th session). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome

FAO (2011) International standards for phytosanitary measures (ISPM 2): framework for pest risk analysis. Secretariat of the International Plant Protection Convention

FAO (2013) International standards for phytosanitary measures (ISPM 11): pest risk analysis for quarantine pests. Secretariat of the International Plant Protection Convention

Fowler AJ, Lodge DM, Hsia JF (2007) Failure of the Lacey Act to protect US ecosystems against animal invasions. Front Ecol Environ 5:353–359

Gederaas L, Moen TL, Skjelseth S, Larsen L-K (2012) Fremmede arter I Norge – med norsk svarteliste 2012. Artsdatabanken, Trondheim

Genovesi P, Shine C (2011) European strategy on invasive alien species. Council of Europe, Wasselonne

Genovesi P, Carboneras C, Vilà M, Walton P (2015) EU adopts innovative legislation on invasive species: a step towards a global response to biological invasions? Biol Invasions 17:1307–1311

Guan Y, Zheng BJ, He YQ et al (2003) Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in Southern China. Science 302:276–278

Hulme PE (2009) Trade, transport and trouble: managing invasive species pathways in an era of globalization. J Appl Ecol 46:10–18

Hulme PE, Bacher S, Kenis M, Klotz S, Kühn I, Minchin D, Nentwig W, Olenin S, Panov V, Pergl J, Pyšek P, Roques A, Sol D, Solarz W, Vilà M (2008) Grasping at the routes of biological invasions: a framework for integrating pathways into policy. J Appl Ecol 45:403–414

Hulme PE, Pysek P, Nentwig W, Vilà M (2009) Will threat of biological invasions unite the European Union? Science 324:40–41

Hulme P, Nentwig W, Pyšek P, Vilà M (2010) How to deal with invasive species? A proposal for Europe. In: Settele LD, Penev TA, Georgiev R, Grabaum V, Grobelnik V, Hammen, Klotz S, Kotarac M, Kühn I (eds) Atlas of biodiversity risk. J. Pensoft, Sofia, pp 165–166

IMF (International Monetery Fund) (2013) World economic outlook database, April 2014. http://www.imf.org. Accessed on 25 May 2014

IUCN (2012) The IUCN red list of threatened species. http://cmsdocs.s3.amazonaws.com/IUCN_Red_List_Brochure_2014_LOW.PDF. Accessed 10 Mar 2015

Jenkins PT, Genovese K, Ruffler H (2007) Broken screens: the regulation of live animal impacts in the United States. Defenders of Wildlife, Washington DC

Jeschke JM, Bacher S, Blackburn TM, Dick JTA, Essl F, Evans T, Gaertner M, Hulme PE, Kühn I, Mrugała A, Pergl J, Pyšek P, Rabitsch W, Ricciardi A, Richardson DM, Sendek A, Vilà M, Winter M, Kumschick S (2014) Defining the impact of non-native species. Conserv Biol 28:1188–1194

Keller RP, Lodge DM, Finnoff DC (2007) Risk assessment for invasive species produces net bioeconomic benefits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:203–207

Leung B, Roura-Pascual N, Bacher S, Heikkilä J, Brotons L, Burgman MA, Dehnen-Schmutz K, Essl F, Hulme PE, Richardson DM, Sol D, Vilà M (2012) TEASIng apart alien species risk assessments: a framework for best practices. Ecol Lett 15:1475–1493

Lodge DM, Williams S, Macisaac HJ, Hayes KR, Leung B, Reichard S, Mack RN, Moyle PB, Smith M, Andow DA, Carlton JT, McMichael A (2006) Biological invasions: recommendations for U.S. policy and management. Ecol Appl 16:2035–2054

McGeoch MA, Butchart SHM, Spear D, Marais E, Kleynhans EJ, Symes A, Chanson J, Hoffmann M (2010) Global indicators of biological invasion: species numbers, biodiversity impact and policy responses. Divers Distrib 16:95–108

Miller JR (2005) Biodiversity conservation and the extinction of experience. Trends Ecol Evol 20:430–434

Miller ML (2011) Laws, Federal and State. In: Simberloff D, Rejmánek M (eds) Encyclopedia of biological invasions. University of California Press, Berkeley, pp 430–437

OIE (2013a) Aquatic Animal Health Code, 22nd edn. World Organization for Animal Health, Paris

OIE (2013b) Terrestrial Animal Health Code, 16th edn. World Organization for Animal Health, Paris

Padilla DK, Williams SL (2004) Beyond ballast water: aquarium and ornamental trades as sources of invasive species in aquatic ecosystems. Front Ecol Environ 2:131–138

Peiris JSM, de Jong MD, Guan Y (2007) Avian influenza virus (H5N1): a threat to human health. Clin Microbiol Rev 20:243–267

Perrings C, Dehnen-Schmutz K, Touza J, Williamson M (2005) How to manage biological invasions under globalization. Trends Ecol Evol 20:212–215

Pimentel D, Zuniga R, Morrison D (2005) Update on the environmental and economic costs associated with alien-invasive species in the United States. Ecol Econ 52:273–288

Pyšek P, Richardson DM, Pergl J, Jarosík V, Sixtova Z, Weber E (2008) Geographical and taxonomic biases in invasion ecology. Trends Ecol Evol 23:237–244

Pyšek P, Hulme PE, Nentwig W, Vilà M (2011) DAISIE project. In: Simberloff D, Rejmánek M (eds) Encyclopedia of biological invasions. University of California Press, Berkeley, pp 138–142

Reed KD, Melski JW, Graham MB et al (2004) The detection of monkeypox in humans in the western hemisphere. N Engl J Med 350:342–350

Richardson DM, Pyšek P (2008) Fifty years of invasion ecology—the legacy of Charles Elton. Divers Distrib 14:161–168

Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (2010) Pets, aquarium, and terrarium species: best practices for addressing risks to biodiversity. Montreal, SCBD, Technical Series No. 48

Simberloff D (2001) Biological invasions. How are they affecting us, and what can we do about them? West N Am Naturalist 61:308–315

Simberloff D (2006) Risk assessments, blacklists, and white lists for introduced species: are predictions good enough to be useful? Agri Res Econ Rev 35:1–10

Simons SA, De Poorter M (eds) (2009) Best practices in pre-import risk screening for species of live animals in international trade. In: Proceedings of an expert workshop on preventing biological invasions held at the University of Notre Dame, Indiana, USA; 9–11 April 2008; Nairobi, Kenya: Global Invasive Species Programme. http://www.issg.org/pdf/publications/GISP/Resources/workshop-riskscreening-pettrade.pdf. Accessed 18 Dec 2013

Takahashi MA (2006) A comparison of legal policy against alien species in New Zealand, the united States and Japan—Can a better regulatory system be developed? In: Koike F, Clout MN, Kawamichi M, De Poorter M, Iwatsuki K (eds) Assessment and control of biological invasion risks. Shoukadoh Book Sellers, IUCN, Kyoto, pp 45–55

Verbrugge LNH, Leuven RSEW, van der Velde G (2010) Evaluation of international risk assessment protocols for exotic species. Institute for Water and Wetland Research, Radboud University Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Vilà M, Pujadas J (2001) Land-use and socio-economic correlates of plant invasions in European and North African countries. Biol Conserv 100:397–401

Vilà M, Basnou C, Pyšek P, Josefsson M, Genovesi P, Gollasch S, Nentwig W, Olenin S, Roques A, Roy D, Hulme P, DAISIE Partners (2010) How well do we understand the impacts of alien species on ecosystem services? A pan-European cross-taxa assessment. Front Ecol Environ 8:135–144

Vilà M, Espinar J, Hejda M, Hulme P, Jarošik V, Maron J, Pergl J, Schaffner U, Sun Y, Pyšek P (2011) Ecological impacts of invasive alien plants: a meta-analysis of their effects on species, communities and ecosystems. Ecol Lett 14:702–708

Wade SA (1995) Stemming the tide: a plea for new exotic species legislation. J Land Use Environ Law 10:343–370

Whittaker RH (1969) New concepts of kingdoms of organisms. Science 163:150–160

Woodward DL, Khakhria R, Johnson WM (1997) Human salmonellosis associated with exotic pets. J Clin Microbiol 35:2786–2790

Acknowledgments

This work was partly funded by Grant P06/RNM/02030 from Junta de Andalucía, the Severo Ochoa Program for Centres of Excellence in R+D+I (SEV-2012-0262), the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación projects Consolider-Ingenio MONTES (CSD2008-00040), RIXFUTUR (CGL2009-7515) and FLORMAS (CG 2012-33801), from the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness. It contributes to COST Action TD1209 Alien Challenge. We thank anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments, A. Frandsen for linguistic assistance, and P. León for continuous support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

García-de-Lomas, J., Vilà, M. Lists of harmful alien organisms: Are the national regulations adapted to the global world?. Biol Invasions 17, 3081–3091 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-015-0939-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-015-0939-7